By Ed Emering

In March 1940, Benito Mussolini met with Adolf Hitler near the Brenner Pass on the border between Austria and Italy. Hitler used this meeting to stroke Mussolini’s ego and convince him to ally Italy with Germany’s war effort. Hitler promised Mussolini the opportunity to achieve great glory for the Italian nation. Buoyed by flattery, Mussolini accepted Hitler’s offer on the condition that the impending German attack on France prove successful. On June 10, 1940, Italy formally joined the German war effort by declaring war on Great Britain and France.

By July 1943, with the tide of war beginning to turn against Italy, Mussolini again met with Hitler in the northern Italian town of Feltre, located in the province of Belluno in the Veneto Region. Members of Mussolini’s Fascist Party had urged him to discuss with Hitler a possible war exit strategy for Italy. Instead, Mussolini requested additional military assistance from Germany. Hitler agreed to provide it, but only on the condition that it be placed under German authority. The tide had finally turned. Italy was now fully under the control of the German forces.

Later that month, Mussolini met with King Victor Emanuel (Vittorio Emanuele III), who had ascended to the Italian throne in 1900. The king informed Mussolini that Italy no longer wanted war and that Mussolini had become the most despised man in Italy.

Caught off guard, Mussolini offered his resignation as prime minister, which was immediately accepted by the king, who then offered Mussolini an armed escort that was actually an arrest. General Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Ababa, commander of the nation’s troops and a Fascist, was then appointed the 41st prime minister of Italy.

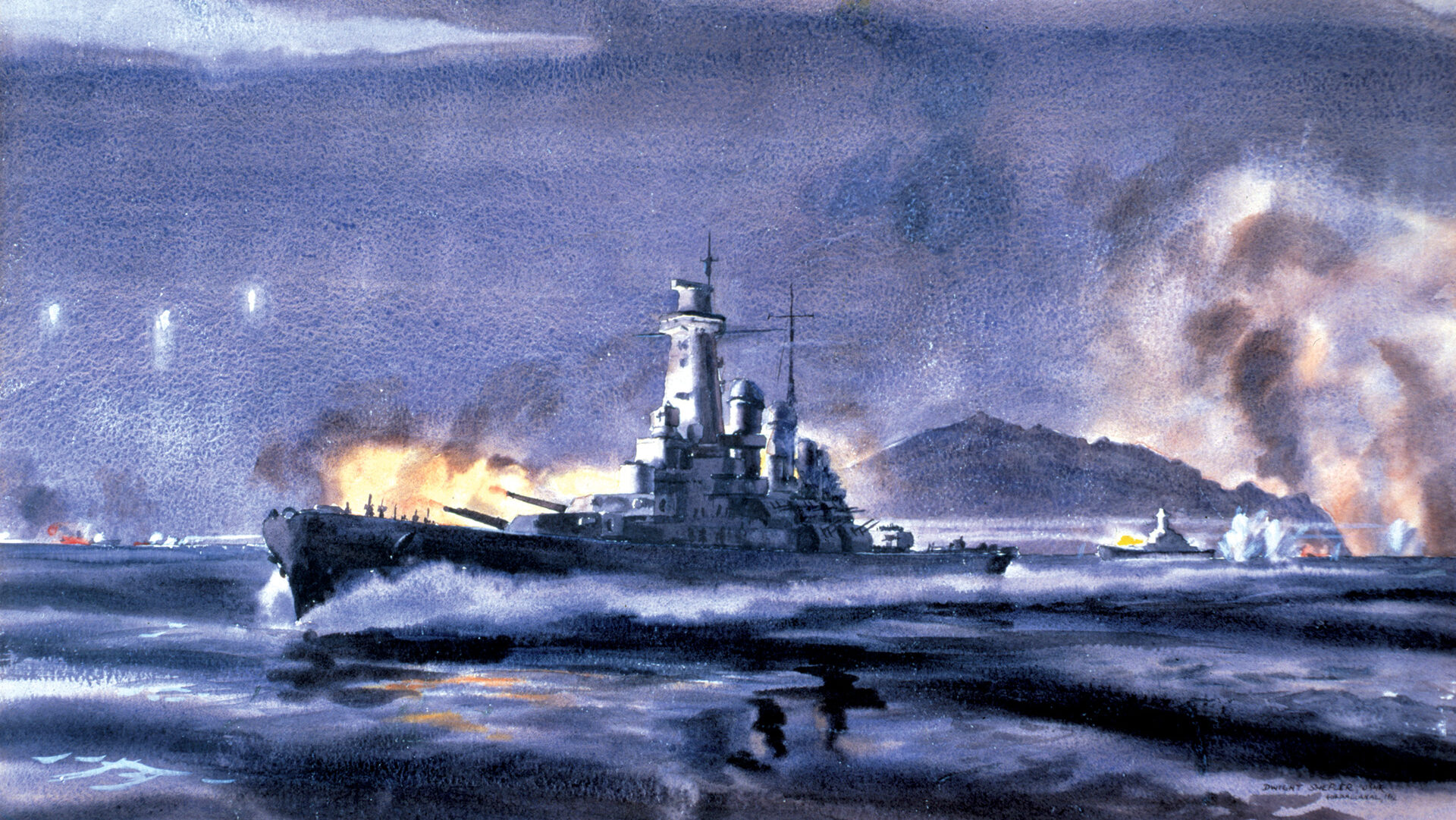

Following the news of Mussolini’s arrest, many fellow Fascist leaders fled Rome. Italians and Germans alike remained silent as the new Badoglio government proclaimed that the war would continue. Even in the face of this proclamation, many Italians began to cheer the removal of Mussolini. Hundreds of people were ordered shot as Badoglio’s government attempted to establish control. As the situation continued to deteriorate rapidly, Badoglio eventually signed a secret armistice with the Allies on September 3, 1943, at Fairfield Camp in Sicily. He fled Rome along with the king when this became public knowledge on September 8. This left Italy’s military in a state of chaos, and German troops implemented Operation Achse, moving rapidly to take over critical defensive positions.

“The War Goes On, But Against Germany”

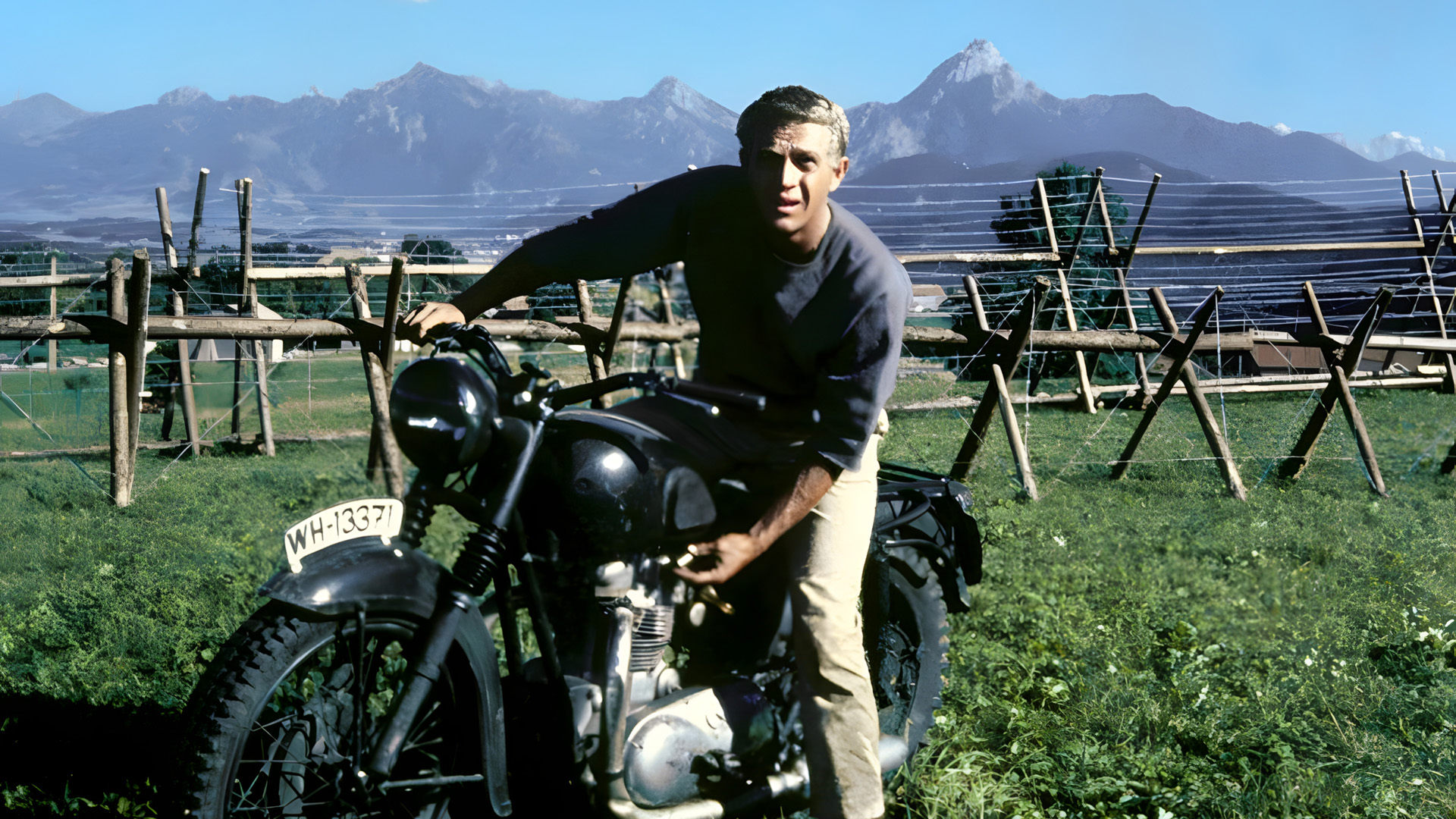

From July 27 to September 12, Italian military intelligence (Servizio per le Informazioni e la Sicurezza Militare, SISMI) and German intelligence agents played a game of cat and mouse while the Germans attempted to locate the imprisoned Mussolini. On September 12, the Germans launched Operation Eiche (Oak). Waffen SS commando Major Otto Skorzeny led a mission to rescue Mussolini from the Campo Imperatore Hotel at Gran Sasso d’Italia in the Apennine Mountains. Along with Nazi Fallschirmjaeger (airborne troops) under the command of Major Harald Mors and Lieutenant Count Otto von Berlepsch, they were able to free Mussolini in a swift and successful operation. Mussolini was then flown first to Vienna and later on to Hitler’s headquarters in Rastenburg, Germany.

Mussolini was flown to a resort at La Rocca delle Caminate in the province of Forli-Cesena and proclaimed head of state of the Italian Social Republic (RSI), with its capital at Salo, situated in the province of Brescia in the region of Lombardy on a long narrow bay toward the southern end of Lake Garda (Lago di Garda) in the shadow of Monte San Bartolomeo. This new Nazi puppet state would also be known informally as the Salo Republic. Mussolini would continue to promote his Fascist ideals and assert that he had been betrayed by disloyal elements among the Italian people. Mussolini initiated a revival of his influence with a new uniformed military including the Republic National Guard, police, and the10th Squadron naval commandos.

While Mussolini was imprisoned in the summer of 1943, it became obvious that a confrontation with Germany was imminent. Lawyer Tancredi Galimberti, a member of the underground Action Party (Partito d’Azione), shouted from a balcony in Cuneo, “The war goes on, but against Germany. For this war there is one means—popular insurrection.”

No one really had the will to fight at that moment. The people hoped that Italy would just be left alone, but they knew this would not happen. It was not until Germany began treating Italy as an occupied nation and the Italians as a subservient people that the populace turned against the German occupation and civil war broke out.

On October 13, the new Italian government declared war on Germany. Italy, at this point, had little to offer militarily, but what it lacked in military armament it made up for with its hatred of the Germans and the Fascist/Nazi ideology. It would still be a difficult battle since Germany had occupied Italy with 22 Army divisions and Mussolini had 6 RSI divisions, which the Italians partisans were compelled to confront.

Catholics, Communists, and Anarchists

Partisan action was generally grouped by political affiliation. The formations were divided among three main groups: the Communist Garibaldi Brigades, the Liberta Brigades (related to Partito d’Azione), and the Socialist Matteotti Brigades. Smaller groups included Catholic sympathizers and monarchists (such as the Green Flames, Di Dio, and Mauri) and some anarchist formations. Relations between the various partisan groups were not always good. The partisan groups in northern Italy, home to the RSI, were far more radical than those in other locales. The Communist Garibaldi Brigades were very well organized.

These units included special teams such as the Gruppo d’Azione Popolare (GAPPISTI), which carried out direct attacks against the Germans and Fascists. The Communists also formed antiscorch squads to prevent the sabotaging of power plants, factories, bridges, and dams. While the largest partisan contingents operated in mountainous districts of the Alps and the Apennines, there were also large partisan formations in the Po River plain.

Partisan membership grew from some 20,000 in May 1944 to more than 200,000 by April 1945. On April 21, the partisans attacked in an organized sweep and took control of all towns and cities that had not yet been reached by the Allies. Over 35,000 partisans had died by the time Italy was fully liberated on May 2, 1945. Hatred of the Fascists ran deep, and the desire for revenge remained unabated.

Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci were stopped by the Communist partisans of the 52nd Garibaldi Brigade (some historians credit the 51st Garibaldi Brigade) on April 27, 1945, on the road to the village of Dongo near Lake Como, as they headed for Switzerland to board a plane in an effort to eventually escape to Spain. The next day, Mussolini and his mistress were summarily executed in the name of the Italian people along with most of the members of their 15-man entourage, primarily ministers and officials of the RSI. The shootings took place in the small hamlet of Giuliano di Mezzegra in the Province of Como.

On April 29, the bodies of Mussolini and his mistress were taken to the Piazzale Loreto in Milan and hung upside down from steel girders at a gas station where they were abused by civilians.

The Cervi Band

No case in the annals of Italy’s World War II history has stood to exemplify the brutality of the Italian Fascists more than the story of the Famiglia (Family) Cervi. Alcide Cervi had joined the Italian Army in 1929. Accused of insubordination, he spent three years in a military prison. While in prison, he developed strong anti-Fascist and pro-Communist sentiments.

When he was freed from prison, Alcide, also known as Father Cervi, became deeply committed to the Italian partisan movement. A staunch Communist, as were so many farmers in the area, he and his seven sons and two daughters exemplified the Italian resistance against the Nazi and Fascist regimes. After moving repeatedly, which was the lot in life of the sharecropper-farmer, the family settled near the fields of Rossi in the town of Erath at the center of the Po Valley in 1934. Here the Cervis introduced modern farming techniques, including crop rotation, and acquired the first tractor in the area in 1939.

At the beginning of the war, the family home became a center for clandestine dissent against Fascism. There, the Cervi Band was formed and dedicated to the partisan struggle. It did not escape the notice of the Fascist authorities. In 1939, Gelindo Cervi had been arrested for anti-Fascist activities. The same fate would befall Ferdinando Cervi in 1942. Gelindo would also be arrested again that same year.

The Cervi Band was charged with various acts of sabotage against power lines used to run munitions factories and also with the distribution of anti-Fascist propaganda. Ferdinando and his cousin, Massimo Cervi, sabotaged power lines near S. Ilario d’Inza. During early October 1943, the band moved to the mountains and formed an armed resistance group.

Later that month, the Cervi Band attacked the police station in Toano. On November 6, it launched a raid on the police station in S. Martino, and on November 13 the group attempted to kidnap a Fascist official, Giuseppe Scolari, in Reggio Emilia. These actions brought them into direct conflict with the Communist Party officials, who preferred to maintain a lower profile. This served to create issues with the band’s ability to find shelter in the area other than at the Cervi family home.

Seven Brothers Executed

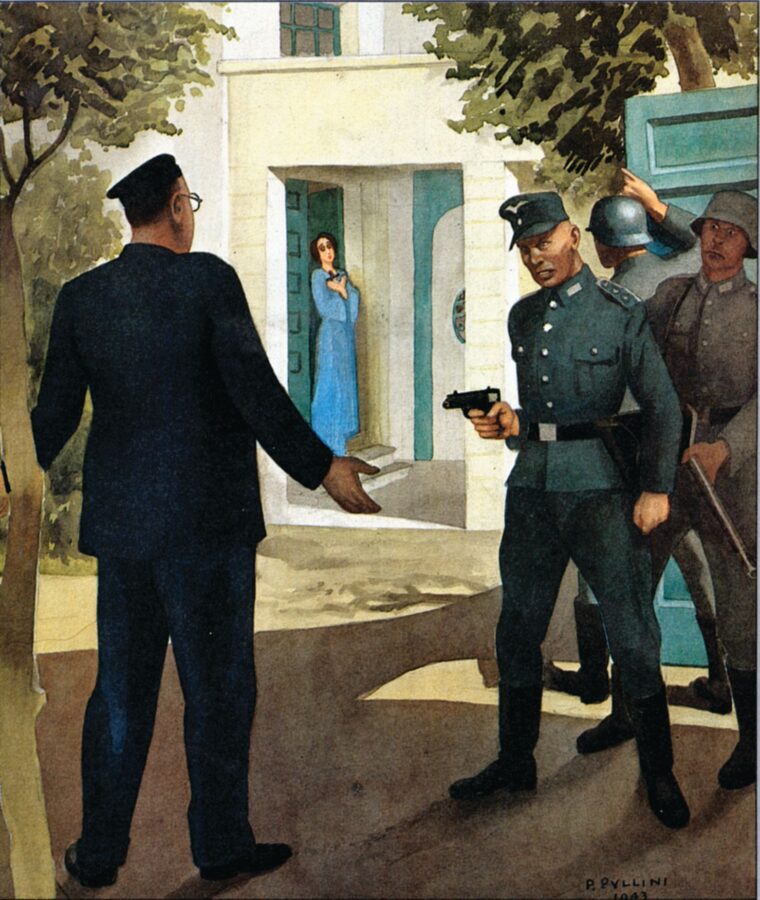

On the night of November 24, 1943, during a “mopping up” sweep, the family was surprised at home by Fascist patrols of the National Republican Guard (Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana, or GNR), a paramilitary force of the Italian Social Republic which replaced both the Carabinieri and the Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurrezza Nazionale (MVSN). A firefight broke out, but after the Cervis had exhausted their ammunition supply, they were forced to surrender. Alcide Cervi and his seven sons—Ettore, Ovidio, Agostino, Ferdinando, Aldo, Antenore, and Gelindo—along with Quatro Camurri, Dante Castellucci, and four non-Italians, were arrested and taken to the prison of St. Thomas in Reggio Emilia. Later the family’s house was sacked and burned by the Fascists.

The four foreigners and Dante Castellucci, who convinced the authorities that he was French, were transferred to prison in Parma. The seven brothers, however, were subjected to torture in order to get them to confess that they were involved in the sabotage. During this time, two high-ranking local Fascists, Senior Militia Official Giovanni Fagiani and Communal Secretary Davide Onfianai, were assassinated on December 15 and December 27, respectively. These acts prompted brutal reprisals by the Fascists.

At dawn on December 28, 1943, with no trial, the seven Cervi brothers, along with their partisan companion, Quatro Camurri, were summarily executed by firing squad at Poligno di Tiro. Their bodies were later buried in unmarked graves at Villa Ospizio Cemetery. To avoid any possible complicity, the death certificates all remained unsigned.

On January 8, 1944, still unaware of the loss of his seven sons, Alcide was able to escape from his cell during an Allied bombing of the prison.

Remembering the Cervi Family

On November 14, 1944, the family’s matriarch, Genoveffa (Genevievezzzz) Cocconi, died. In October 1945, following the end of the war, Alcide was finally able to hold a solemn funeral service for his wife and children. For his commitment to the partisan cause, he was presented with a gold medal created by Italian sculptor and artist Marino Mazzacurati. The obverse bears the effigy of Alcide Cervi. The reverse contains an oak tree with seven branches for the seven brothers. Alcide passed away at the age of 90 in 1975.

A second commemorative medal, issued by the ANPI (Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d’Italia) of Reggio Emilia, intended for wider distribution, was also struck. The obverse bears the effigy of Alcide and his spouse, Genevieve. The curved inscription in the upper portion reads, GENOVEFFA E ALCIDE CERVI (Genevieve and Alcide Cervi). The reverse depicts a brick wall to the left and lists the seven sons to the right from top to bottom, ETTORE, OVIDIO, AGOSTINO, FERDINANDO, ALDO, ANTENORE, GELINDO, and further to the right of each name, a five-pointed star. At the bottom of the reverse is the curved inscription, A.N.P.I. REGGIO E.

Aldo Cervi remains a lasting symbol of the partisan cause and a legendary heroic figure among the anti-Fascist partisans, especially the politically powerful Communists. A local Communist historian, Renato Nicolai, assisted Alcide with the publication of his 1955 book, I Miei Sette Figli (My Seven Sons), which helped memorialize the atrocity.

The family’s home is now Museo Cervi, a museum dedicated to the Italian Resistance. In Addition, the ANPI has continued to actively support and promote partisan causes, recently protesting the 2008 Spike Lee film, Miracle at St. Anna. The film tells the story of the Nazi atrocity at Sant’Anna di Stazzema, a village in Tuscany in central Italy.

Massacre of the Govoni Family

On August 12, 1944, retreating members of the II Battalion, SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 35 of the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division, commanded by Hauptsturmfuhrer (Captain) Anton Galler, rounded up 560 villagers and refugees, mostly women, children, and older men, shot them, and then burned their bodies. The film infers that the Nazi slaughter of innocent villagers may have been a direct result of the collaboration of a partisan with the Nazis. It is an indication of how deep feelings continue to run, more than 65 years after the war ended.

Anti-partisan operations were a key assignment of the new RSI regiments formed by Mussolini in 1943. Organized on September 24, 1943, the Italian SS Legion—eventually designated the 29th Waffen Grenadier SS Division der SS Italianische Nr. 1 or La Brigata d’Assaulto, Miliza Armata (the brigade was eventually upgraded to a division)—was made up of some Fascist volunteers as well as others who were former inmates of prison and labor camps later released to serve the Germans. Their operations were primarily directed against Communist partisans in German-occupied northern Italy. They were notorious for the ferocity and brutality of their antipartisan campaign. Hatred for the members and supporters of the RSI ran deep among the partisans.

The brutal actions of the Fascists and Nazis, particularly the Waffen SS, spread a deep hatred of them among the partisans and their sympathizers, which spilled over even after the war officially ended. An example of this hatred is in the seldom told tale of the Govoni family.

In the village of Pieve di Cento close to Bologna in northern Italy, lived the Govoni family. Cesare Govoni, his wife Caterina, and their six sons and two daughters were Fascist supporters. Only two of the sons, Dino and Marino, a veteran of the African Campaign, actually joined Mussolini’s RSI.

On April 21, 1945, Bologna was liberated by Polish troops and Brigata Maiella partisans. Following the conclusion of hostilities in 1945, a general amnesty was declared, but it suited Communist partisan purposes to spread terror everywhere to achieve greater political control.

On May 8, 1945, Communist partisans began rounding up Fascist supporters in the area. At a nearby farmhouse, 12 suspected Fascist supporters were killed. Initially, the partisans seized only Marino Govoni on the night of May 10. The other Govonis felt safe because they had been interrogated and cleared of any complicity with the Fascist regime. Later. the partisans rounded up Augusto, Dino, Emo, Primo, Giuseppe, and their sister, Ida, who was nursing her three-month-old child at the time. They were bundled onto a truck and driven to a nearby farmhouse on the estate of Emilio Grazia. The Govonis were joined by 10 other prisoners: Alberto Bonora, Cesarino Bonora, Ivo Bonora, Guido Pancaldi, Alberto Bonvicini, Giovanni Caliceti, Vinicio Testoni, Ugo Bonora, Guido Mattioli, and James Malaguti. All were resolute anti-Communists.

The infamous organizers of the arrests were thought to be the Paolo Brigade of the 7th Gruppo d’Azione Partigiana (Partisan Action Group). For hours, the prisoners were beaten and tortured in the most brutal fashion. The last screams were heard around 11 pm. The broken bodies of the 17 prisoners were later found dumped in an antitank trench. Fearing further further atrocities by the Communist partisans, strict silence surrounded the events of the evening. Only the parents of the seven Govoni victims attempted to shed light on the incident.

On February 8, 1953, a trial for the perpetrators of the Govoni killings was finally held in absentia at the courthouse in Bologna. Four life sentences were meted out by the court. Unfortunately, the actual perpetrators of the massacre had long since fled behind the Iron Curtain and were beyond the reach of the Italian justice system.

Two Different Families, Two Different Atrocities

A comparison of the two atrocities yields interesting conclusions and reveals that post-war bitterness has lingered for many years in Italy. In both cases, seven siblings were killed. The seven Cervis were all male, and all were partisans who took an active role in the civil war, carrying out guerrilla-style terrorist raids against Nazi and Fascist troops, and even killing RSI soldiers. The seven Govonis included one woman, and only the oldest two brothers had actually been active supporters of the Italian Social Republic (RSI), but had never committed crimes. The other five siblings were not involved in Fascist politics at all.

The Cervis were killed during the war, as a result of an act of war. The Govonis were killed after the war had ended. Following the cessation of hostilities on May 8, 1945, the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale (CLN or National Liberation Committee), the underground multiparty political entity of Italian partisans whose members shared opposition to the Germans and Fascists during World War II, issued orders to arrest only people who had been involved in the atrocities perpetrated by Mussolini’sRSI regime in order to bring them to trial. It did not authorize summary executions.

The Cervis have been and still are widely commemorated. Every Italian knows their story. Many streets and squares have been dedicated to them in many cities, and even a state-financed museum (Museo Cervi) has been established in their memory.

The Govonis have been intentionally forgotten, and only in the recent years has anyone begun to mention this atrocity. There is still significant resistance to resurrecting their memory, particularly from those who believe that the partisan movement formed the basis of the current Italian Republic. Many still view the people involved in Mussolini’s social republic as criminals and feel that anything that was done to them was fully justified.

I would be so grateful if someone can reply to me regarding names of living Resistance fighters in Italy.

I’m crafting a book that deals with Holocaust survivors and Resistance fighters.

I would so love to commemorate the memories of brave fighters by talking to survivors and giving them an honorable mention in my novel.

If you have time check out the USC Shoah Foundation’s Virtual History Archive, it is free to make an account and you will gain access to interviews from Italian Jewish Survivors and Partisans. Not sure if any are still alive, but I’m sure there is other testimony that can offer you some inspiration for where to turn next.

Other Links:

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/italy-virtual-jewish-history-tour#holo

http://www.jewishpartisans.org/countries/italy