By Eric Niderost

Soochow was a mongrel dog with a remarkable gift for self-preservation. A homeless stray, he attached himself to some U.S. Marines, men of the Fourth Regiment who were stationed in China. The dog was first tolerated, then accepted, and finally celebrated as a full-fledged leatherneck. Soochow eventually became a “sergeant,” but he earned his stripes in one of the most remarkable tales of survival and courage of World War II.

Surviving Against the Odds

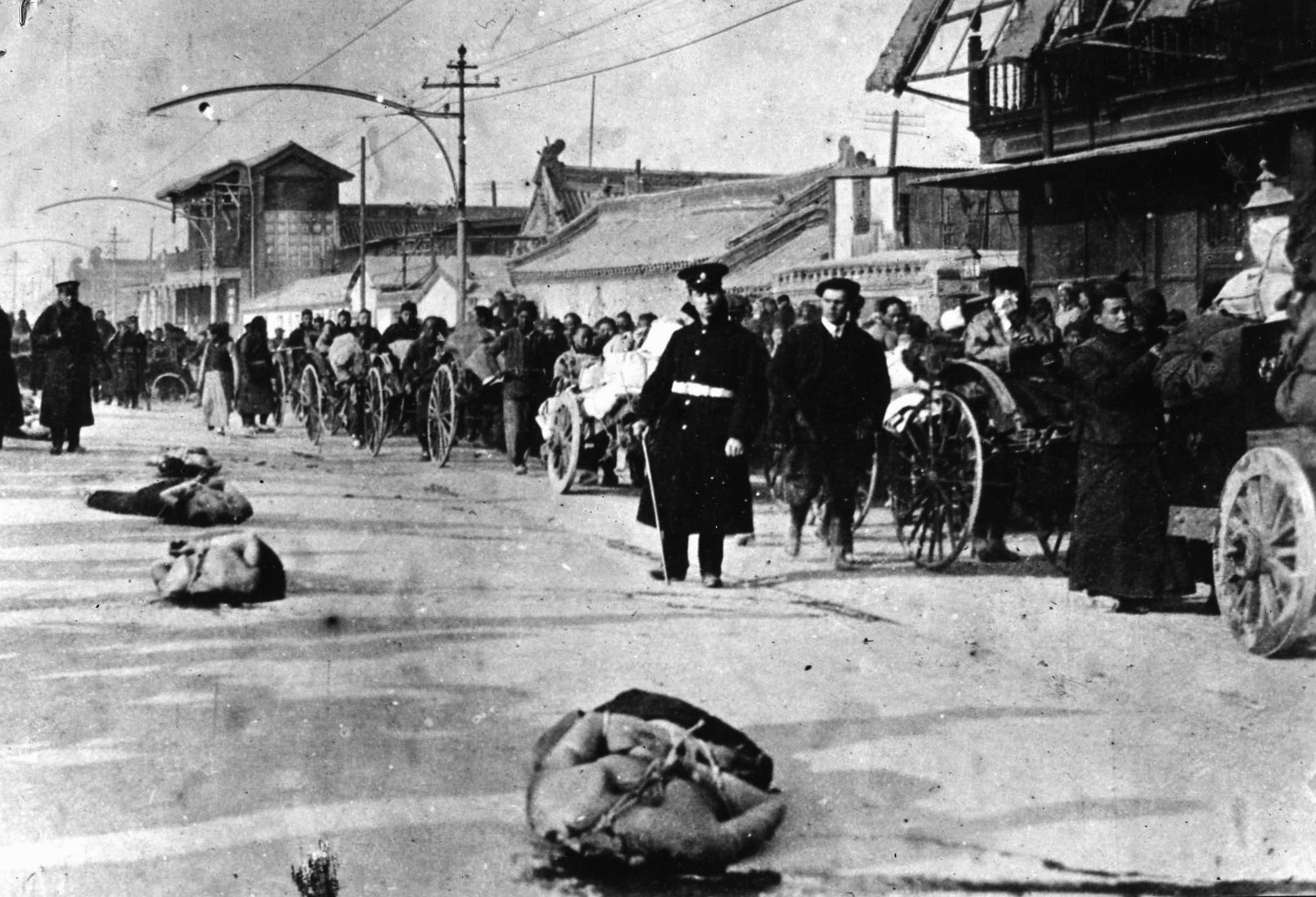

The story begins in 1930s Shanghai, then an international city dominated by foreign interests. China was in turmoil, with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists battling Communists for control of the country. Sensing weakness, Japan began a series of aggressive moves on the stricken nation. Manchuria was seized in 1931-1932, but the Western powers were too self-absorbed in the Depression and its economic crisis to do much about it.

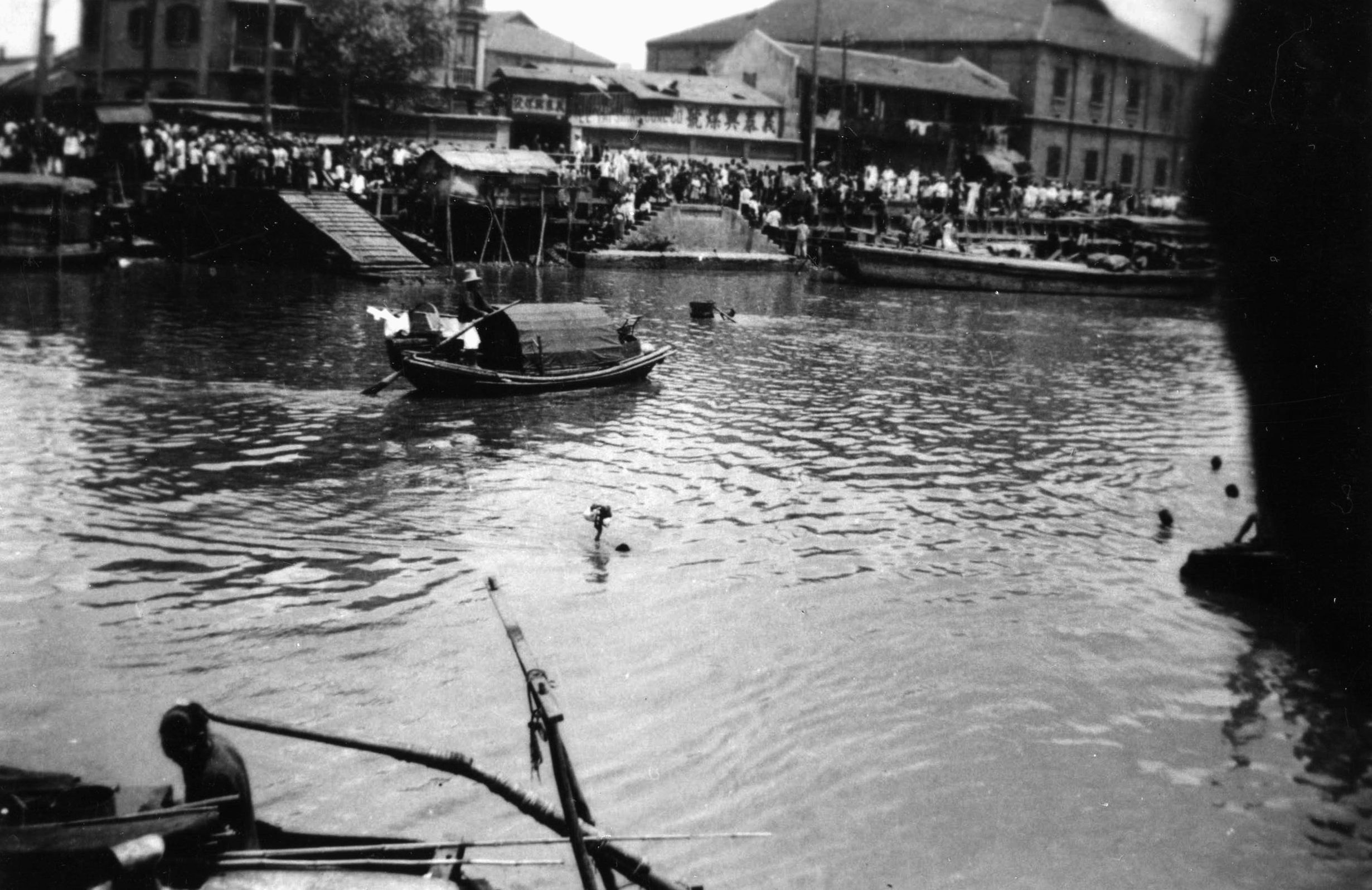

Soochow was probably born in the summer of 1937, a decidedly inauspicious time to enter the world. He probably saw the light of day along Soochow (now Suzhou) Creek, a sinuous waterway that snakes its way though Shanghai before emptying into the Whangpoo (Huangpu) River. Soochow Creek went through the heart of the International Settlement, a special territory ruled by a body called the Shanghai Municipal Council. The council was a thinly disguised oligarchy of British and American businessmen, though the Chinese and even Japanese had some seats.

The Settlement and the neighboring French Concession were the calm eye of China’s political hurricane, islands of relative safety and peace. This condition was due in no small part to the presence of foreign troops, including contingents from the United States, Great Britain, France, and Italy. The 4th Regiment of the United States Marines had been stationed in Shanghai since 1927, its primary mission to safeguard the lives and property of Americans there.

Soochow Creek was home to an entire population of Chinese, boat people who rarely seemed to venture onto dry land. Clustered together in makeshift floating communities, they used the waterway as a toilet and source of water. The creek was little more than a sewer, and the boat people were desperate enough to eat anything that would assuage their constant hunger. Poverty and disease were ever present.

How Soochow managed to survive his first two or three months is something of a mystery—and a miracle. It was a credit to his mother that she managed to keep her litter, if indeed Soochow had any brothers and sisters, out of the stew pot. Puppies are particularly vulnerable the first two weeks or so of their lives, when their eyes are closed.

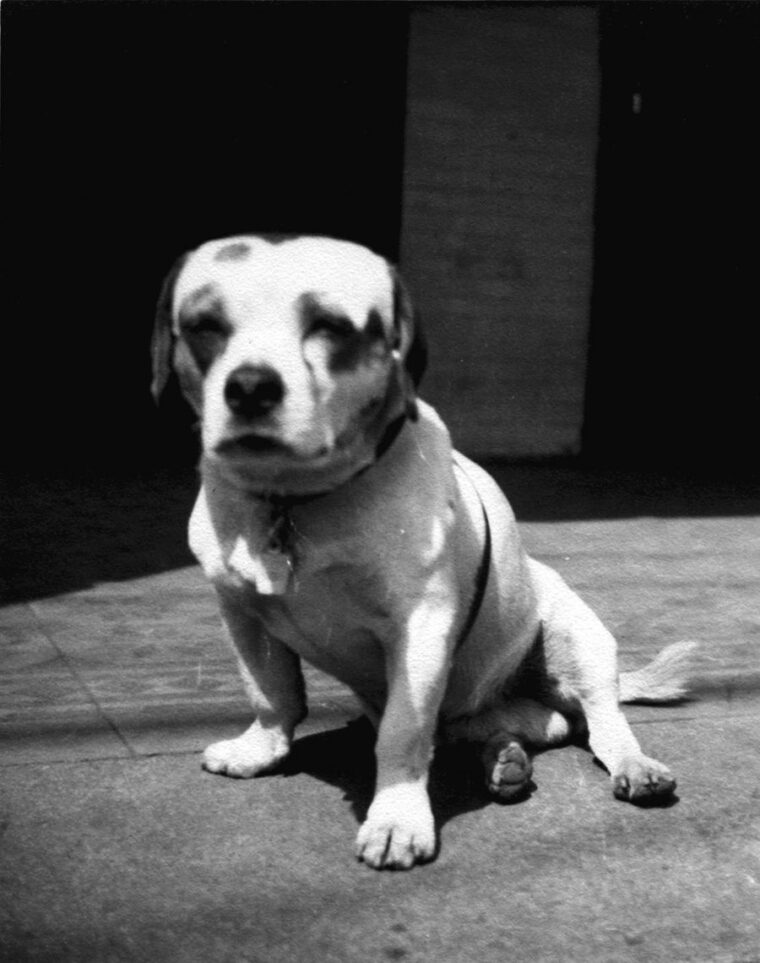

Soochow was a mongrel, probably a bulldog-terrier mix, with a dash of one or two other breeds. He was short and stocky, never weighing more than about 35 pounds when fully grown. His fur was largely white, with some dark spots, and his ears drooped down like a hound’s. He was an ugly dog in some respects, but his face was redeemed by large, black, expressive eyes, gleaming with intelligence.

A Puppy in the Marines

Soochow’s birth coincided with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War. Hoping to gain Western sympathy and support, Chiang confronted the Japanese Army at Shanghai. During the late summer and early fall of 1937, Shanghai was the scene of some of the bloodiest urban fighting ever recorded. Soochow Creek became a kind of unintentional border, separating the war-torn Japanese-held areas from the Settlement’s southern segment largely controlled by the Anglo-Americans.

Eventually the Chinese were forced to retreat to the west, but Soochow Creek remained a barrier as potent as the Berlin Wall was to become decades later. Bridges across the creek were still intact but were closely guarded as checkpoints. The 4th Marines were assigned a defense sector along the creek, which included the Wu Chin Bridge. The southern end of the span was guarded by a U.S. Marine sentry, while the other side was patrolled by a Japanese soldier.

There are several different versions of how Soochow “joined” the Marine Corps, but they differ in detail, not substance. In one popular version, Soochow, then an underfed puppy, took shelter in the Marine sentry box during a heavy rainstorm. Some stories omit the rain but agree the little mutt guarded the box with the tenacity of a bulldog. It seems the puppy did not like Chinese people, barking his head off when they passed by.

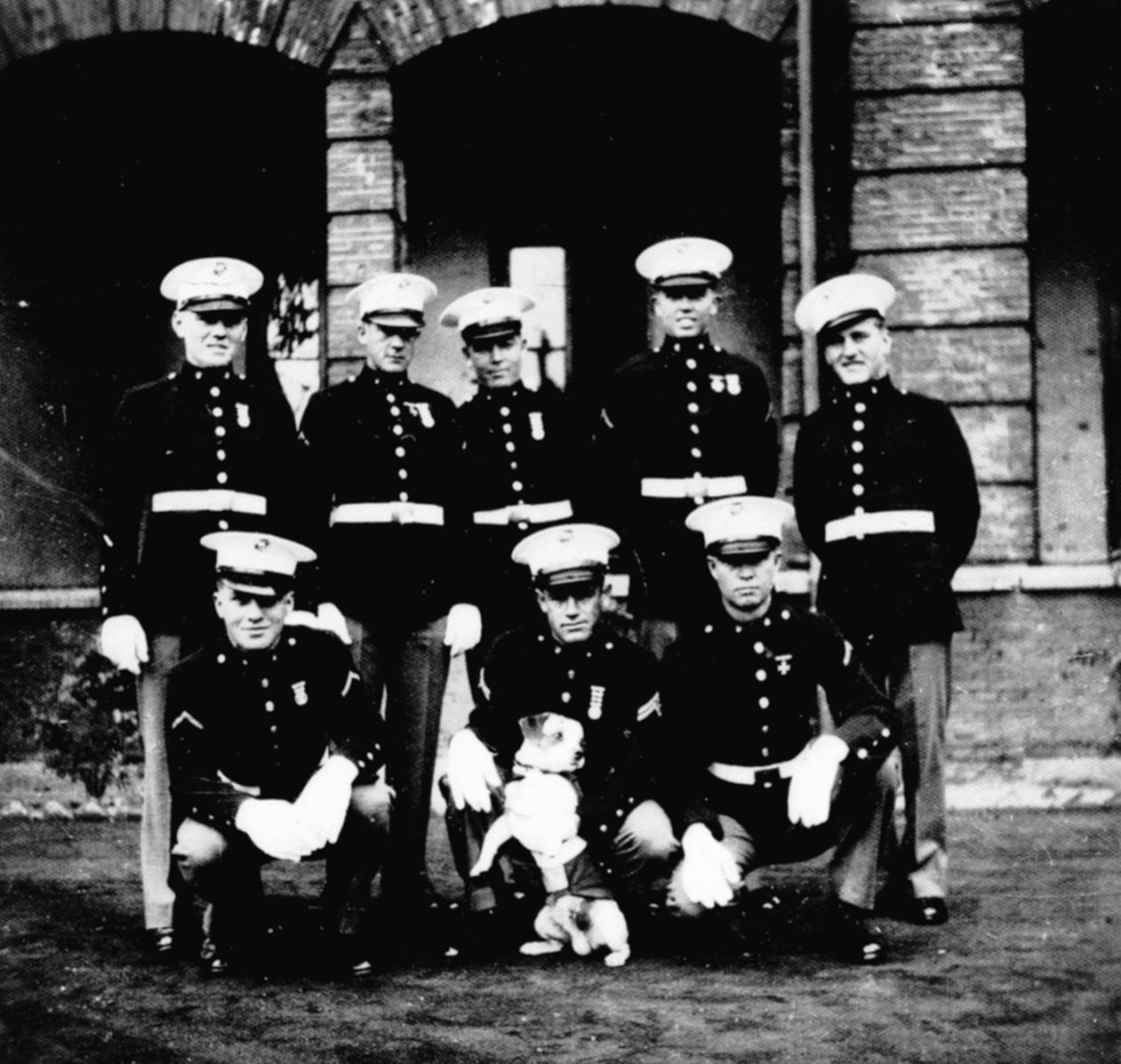

The post was manned by Marines of B Company, 4th Regiment, and Soochow probably went through several guard changes before someone had the bright idea to adopt him. One version maintains it was a Private Ford who smuggled Soochow into the B Company billet. No matter. Once established, the little dog, dubbed Soochow or “Sooch” for short, made himself at home.

This was strictly against regulations—official regulations, anyway. Somehow, company commander Captain Joseph P. McCaffery was won over, and the dog became a kind of unofficial mascot. No one Marine was his master; he was friendly to all. He also liked to travel around, sometimes visiting Headquarters Company, or even Motor Transport a couple of blocks away. Nightfall would find him back in the B Company compound, a converted mansion of sorts.

Sooch was friendly to those he knew, but was also an independent cuss who was not particularly lovable. There are lots of stories about Soochow, tall tales that would put Lassie to shame. There are accounts of him standing to attention during reviews and even lifting a paw in salute. Pure fantasy. As one Marine put it, “Soochow was worthless. He couldn’t fight his way out of a wet paper sack. He was ugly as sin, but the guys loved him.”

A Uniformed Member of the Service

Soochow’s life was in some respects like any China Marine. Shanghai was a sought-after duty station because it was a fabulous city where even a private’s meager $21.00 a month could go a long way. Food, drink, and entertainment were cheap, even by 1930s Depression standards. Shanghai was one of the great cities of the world, and for many young Marines, many of them literally off the farm, it was a movable feast of sights, sounds, and experiences.

And there were temptations. If Shanghai was the “Paris of the East,” it was also called the “Whore of the East,” where gambling dens, prostitution, and opium consumption were common. It was tough to keep a regiment in fighting trim in such an urban environment, especially after the Japanese Army occupied the area surrounding the International Settlement, making Shanghai a lonely island.

Still, such matters were an officer’s concern. The average leatherneck simply enjoyed the experience, and Soochow was along for the ride. Besides guard duty, Marines would participate in route marches, to the order of “route step, keep step.” Once a week there would be a 20-mile hike with fully loaded packs. Soochow would march right along, and in many cases he would be the first out of the compound gate.

When trouble was afoot, it was thought best to have Marines in uniform at all times. Before 1937, the men had been permitted to wear civilian clothes, but times had changed. The men of Company B decided that Soochow needed a uniform, too, and so they all chipped in to get him outfitted. Even today, a person can get fine tailor-made clothes in Shanghai, and this was also true in 1938. A Chinese tailor made three outfits: greens, khakis, and dress blue for formal occasions.

It was said that Soochow enjoyed wearing a uniform, though he did not wear one all the time. After a time Sooch was promoted to private first class, and a red chevron was sewn on his uniform just above his front legs. Unfortunately he would sometimes get in a dog fight, have his uniform ripped, and get into trouble with the brass. Punishment included being busted back to buck private!

Soochow on Liberty

Soochow accompanied the men when they went on liberty, his buddies making sure he was properly uniformed for the outing. They made the rounds of various bars and clubs, Sooch at their side. The dog sometimes might be given a bowl of rum and Coca-Cola, but he generally preferred beer. Sometimes he would get drunk, much to the delight of his equally inebriated fellow leathernecks. They would roar with laughter as Soochow tried to walk with rubbery legs, falling over every few shaky steps.

During one of these excursions the boys decided it would be great fun to send Soochow back to the barracks alone, riding a rickshaw. Shanghai was no stranger to exotic sights, but to see a uniformed little mutt proudly riding around town must have puzzled the natives. One can imagine the local Chinese thinking to themselves, “These foreigners are ugly, but this one takes the cake!” The ride was so successful it was repeated many times thereafter.

But the rickshaw story does not end there. Most rickshaw pullers were honest, but a few tried to dump Sooch far short of the Company B billet entrance. The dog would refuse to get off, his snarling and growling sending an unmistakable message to be delivered to the right address. He would only be satisfied when an obviously chastened rickshaw puller deposited him at the compound gate.

The Marine Club on 722 Bubbling Well Road was a favorite liberty spot, a converted mansion that featured such amenities as a bowling alley, library, restaurant, billiard room, NCO bar, and private’s bar. As long as visitors obeyed the rules, all were welcome. Marines would come to the club with beautiful Chinese or White Russian girlfriends on their arms. The club, quite luxurious and famed throughout the Far East, also boasted the finest soda fountain in Asia.

Soochow was usually welcomed, but once he peed on a table leg and incurred the wrath of Sergeant Kenneth W. Mize of the Service Company, a club manager. Old Sooch was suspended in a harness an inch or so above the floor, not in any discomfort but plainly embarrassed by the situation. The “crime” was not repeated.

A Heroic Recovery, and Time in the Brig

Some of Soochow’s character was revealed when he suffered a terrible accident in the fall of 1940. He was doing his usual patrol rounds, playfully barking and nipping at passing rickshaw pullers or Chinese on bicycles when a Marine truck accidentally ran him over. Soochow had a fractured spine and was taken immediately to the veterinary hospital on Gordon Road. The doctors felt there was no hope and suggested putting the dog to sleep.

The Marines refused, knowing Soochow’s indomitable courage and will to live. After a time in the hospital, he was taken back to the Company B barracks for further recuperation. Soochow pulled through with the help of his buddies and was pretty much his old self.

Soochow’s attitude was always aloof and dignified. He played no favorites, visiting various Marine locations and units. He could be friendly and even wag his tail, but only on his own terms. In that way, he was much like a cat. Soochow was not the stereotypical faithful hound, eager to please his masters like a Lassie or Rin Tin Tin.

The dog’s most serious trouble with the brass came when 4th Marines commander Colonel Eugene Collier caught Soochow “saluting” the flagpole with a raised hind leg. The dog was summoned to the CO’s office and given a good dressing down. “If you are going to be a Marine, you are going to be treated as a Marine, and Marines do not piss on the flagpole. Ten days cake and wine!”

This was time in the brig, and the term “cake and wine” meant a diet of bread and water. The brig was at the Motor Transport compound, where the mess was located. Marines felt sorry for Soochow and saved choice tidbits to feed him though the bars. Soochow actually gained weight in the brig, prompting this directive: “Will men please refrain from tossing food in the brig. The deck is cluttered with so much chow there’s no room for the prisoner to lie down.”

Following the Marines to the Philippines

Shanghai’s International Settlement seemed immune to the war and bloodshed that plagued China and much of the world, but it was not to last. World War II broke out in Europe, and relations between Japan and the United States began to sour. Japanese agents infiltrated the Settlement, wreaking havoc. Anyone who spoke out against Japanese aggression, including many Americans, was targeted for assassination.

By mid-1941, it was plain that the United States and Japan were on a collision course. Admiral Thomas Hart, commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, tried to persuade Washington to withdraw the 4th Marines. Simply put, their position was untenable. Some 700-odd Marines could not hope to hold off the 300,000 Japanese troops stationed in the area.

The regiment was finally withdrawn in late November 1941. The destination was the Philippines, not the States, which was unfortunate in light of future events. The 2nd Battalion left Shanghai on November 27 aboard the liner President Madison. A day later, Colonel Samuel Howard and 1st Battalion marched down Nanking Road to the Bund waterfront, their band playing martial tunes.

When they arrived on the docks, a lighter took them to the waiting President Harrison for their journey to the Philippines. The night before, a certain Private First Class Soochow had been smuggled aboard. For better or worse, the dog was about to share his regiment’s fate.

Japanese warships shadowed the President Harrison but finally wearied of the cat-and- mouse game and departed. The rest of the trip was uneventful, and the Marines arrived safely at Olongapo in the Philippines on December 1. Olongapo was a naval base on Subic Bay on the island of Luzon.

War Begins

The Marines were mostly in canvas tents, and their personal belongings were housed in a great warehouse. Soochow quickly adapted, and though he visited other companies he still bunked with Company B. News of Pearl Harbor arrived on December 8, 1941, because the Philippines are across the International Date Line. The United States was at war with Japan. A large Japanese invasion force soon appeared at Lingayen Gulf off Northern Luzon. The enemy proved impossible to stop, so General Douglas MacArthur ordered a withdrawal to the Bataan Peninsula.

MacArthur was commander of the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), composed of some 31,000 U.S. Army troops and 120,000 men of the Philippine national army. He wanted operational control of all naval and Marine units, and eventually Admiral Hart granted his wishes.

The 4th Marines were withdrawn from Subic Bay and placed on Corregidor, the island fortress that guarded Manila Bay. Located about two miles from the Bataan shore, this tadpole-shaped real estate was honeycombed with artillery batteries, many boasting 12-inch guns on disappearing carriages and powerful mortars. There had been some attempt at modernization in the 1930s, but most of the emplacements were of World War I vintage or earlier.

The widest part of the island was known as topside, while middleside was a small plateau containing more batteries and some barracks. The lowest part of Corregidor, named bottomside, was where the docks and a small town called San Jose were located.

Japanese aerial bombardment began on December 29, 1941, an attack that lasted two hours. Many buildings on Corregidor were badly damaged or destroyed. Other attacks followed, though the month of January could be considered the relative lull before the storm. The real onslaught began in February, when Japanese heavy artillery added their shells to the rain of bombs. Corregidor became a moon-cratered hell on earth where ear-splitting roars and eviscerated, rumbling earth became part of daily life.

Advantages of a Canine: A Keen Ear and a Light Foot

It is almost unbelievable that Soochow could have survived all this, and if he escaped a Japanese shell or bomb he could have fallen prey to the cooking pot. Supplies grew short, and rations were cut until the men were living on 31 ounces of food a day. Cavalry horses were soon slaughtered and their meat distributed to the garrison.

Under these conditions it is not surprising that Sooch might have ended up on the menu. The Marines would never, ever have done this, but there were plenty of other personnel with less emotional attachment to the dog. The Marines were told that some Army cooks wanted Soochow as their mascot. To win him over, the cooks fed the dog scraps from their meager supplies, and it was said at times Soochow was so full he could barely walk.

Soochow accepted the bribes but never abandoned his Company B buddies. Every night he would waddle back to where the Marines were entrenched. Old Sooch was loyal to his friends, but maybe he also sensed that he was being fattened up for other purposes and stayed away. It was said that Soochow was the only member of the Corregidor garrison who gained weight.

The Marines also discovered that Sooch had a hidden talent. He had a kind of canine radar that could detect incoming Japanese bombers long before they were over Corregidor. Soochow might be taking a noontime siesta and then suddenly cock an ear, stand up, and point north. Once up, Sooch would start whining and then seek shelter in the nearest foxhole. Word quickly passed up and down the line that Japanese bombers were on their way.

In the early days of the siege some doubted Soochow’s abilities, but after the dog successfully predicted several air raids most became true believers. Many of the Marine companies were on the beach areas, where they were joined by other personnel. This included U.S. Navy sailors, whose ships had been sunk or scuttled in the opening weeks of the war.

One bluejacket recalled Soochow’s uncanny ability to walk on minefields unscathed. “The little bastard used to come up to my foxhole,” the sailor remembered, “starts barking and it scared the heck out of me! You’d have thought I was a Jap the way he carried on! Then, I see him walking up and down the beach, and I just knew he’d step on one of those mines and blow himself up but I guess he didn’t weigh enough to touch one off.”

The Philippines Falls

The heroic defense of the Philippines had delayed the Japanese timetable of conquest, but by May 1942 it was clear Corregidor could not hold out much longer. The island was being pounded daily.

Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma organized a Japanese amphibious assault on Corregidor for the night of May 5, 1942. There is some evidence to conclude that Soochow was placed in the Navy intercept tunnel near Monkey Point for his own protection. Sooch was lucky to have such buddies because within a few hours all hell broke loose.

After heavy fighting the Japanese managed to secure a foothold on Corregidor, though their casualties were high. But once they managed to successfully land some tanks, there was no doubt about the eventual outcome. Lt. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, who succeeded MacArthur as commander of U.S. and Filipino forces, sadly surrendered to prevent a slaughter of his men.

The Japanese assembled all their prisoners, some 15,000, at what was called the 92nd garage area. It was on an island beach, nothing more than a large field of some two or three acres that was surfaced in concrete. It had once been a landing area for amphibious seaplanes, then it was a motor pool. Some Filipinos and officers found shelter in some bullet-riddled hangars. The rest had to spend days exposed to the broiling tropical sun and intermittent torrential rains.

The Japanese guards were lax at first, permitting POWs to scrounge for food around the island. But the men were finally shipped across Manila Bay to begin their long, brutal imprisonment. Ragged and hungry, they were marched through the streets of Manila in a vain attempt to humiliate them and break their spirits. They finally were placed in Bilibid Prison, but this prewar facility was only a brief stop to their ultimate destination.

The American POWs were marched to Manila Station, where they were packed like sardines into boxcars. The temperatures soared above 100 degrees Farenheit, and they were packed so tightly that men who passed out remained upright. Many were suffering from diarrhea and dysentery. The heat, starvation, exhaustion, and sickening stench had to be endured for the whole journey, a living hell that lasted 10 hours. Their final destination was Cabanatuan, where a large POW camp was located. It had once been a Filipino Army depot but had been converted for more sinister purposes. Once they arrived, they had to endure a forced march of seven miles before reaching the camp gates.

The camp was basically a compound surrounded on all sides by barbed wire. The accommodations were rude shacks, with no beds or bedding or even flooring in some cases. Toilet facilities were open ditches that quickly filled with human waste. Japanese rules were draconian. Beatings and executions were regular occurrences.

Soochow the POW

Soochow was at Cabanatuan, but how he got there remains something of a mystery. Marine testimony after the war credited Pfc. Robert Snyder, who was from B Company. Witnesses maintain that it was he who smuggled Sooch aboard ship when they left Shanghai, and it was he who took the dog to Corregidor. But how he managed to keep Soochow alive after the surrender is nothing short of a miracle.

Life at Cabanatuan was grim, and death was ever present. The POWs were starving, and a gnawing hunger became a way of life. Cats, dogs, and even rats were all fair game for the cooking pot. A cat was considered something of a rare treat, even a delicacy, because the animals were wary and very hard to catch. Under these conditions Soochow’s life was in grave danger, and usually one of his Marine buddies had to keep an eye on him.

The Japanese guards did not particularly like Soochow, and sometimes they made half- hearted attempts to bayonet him. Maybe it was a game to them, or maybe they just were going through the motions. Certainly, they knew if they killed Sooch they would probably have a major riot on their hands. If they had really wanted to get him, they could have, but for some reason they tolerated the little brown and white mutt.

Getting food for Soochow became more and more of a problem. He was a full-fledged member of the Marines, but in Japanese eyes he did not merit a food ration. To keep the dog alive Snyder would go around and collect a grain or two of rice from each man. This was difficult because rations were so scanty and even a few grains were precious. But the Marines gladly contributed because Soochow was their buddy, a symbol of the regiment and its Shanghai glory days.

Soochow learned to eat whatever he could catch, including bugs and lizards. It was a far cry from the days when he would eat thick steaks and lap beer, but the cruel conditions never broke his spirit or lessened his courage. This was evident during tenko, or prisoner roll call. The emaciated POWs would assemble in ranks as Japanese guards counted them off. Summoning what strength he had, Soochow would come up and bark at the guards, an act of defiance that the prisoners must have appreciated. He also kept his dignity, an aloofness that rose above the terrible situation.

The arduous existence had begun to take its toll, and by 1944-1945 Soochow was a shadow of his former self. He was nearly skeletal, wasted away to the point where his ribs could be counted. Scurvy caused his hair to fall out in patches, and sores erupted over his body. Yet, even then he could be heard scrambling under the prison barracks in search of rats or other vermin to eat. His large brown eyes expressed his courage and resolution, and he could still manage to weakly wag his tail.

Late in the war the Japanese began to evacuate American POWs to Japan. They were transported aboard the notorious hell ships, where hundreds of men were packed in foul holds with little if any food and water. The hell ships were also unmarked, which led many to be tragically sunk by unsuspecting American submarines.

Cabanatuan was slowly being emptied, and among the truckloads of departing prisoners was Marine “Frenchy” Dupont and his canine companion Soochow. Eventually Soochow found himself back in Bilibid, where the Marines had briefly been incarcerated in 1942. It was at Bilibid that Soochow had his closest brush with death. He got into a fight with a large rat and was badly wounded. Poor Soochow’s shoulder was torn open, the bloody wound susceptible to infection in the dirty conditions.

His Marine friends did what they could, but there was no medicine for humans, much less for animals. It was touch and go for a time, but somehow Soochow pulled through. He was still underweight, scurvy-ridden, and pock-marked with sores. Sooch had a strong will to live, but by January 1945, it was clear that he could not have survived many more months. The same could be said of the human prisoners.

The POWs saw more American warplanes over Manila and knew liberation must be near. Their greatest fear was to be evacuated to Japan at the eleventh hour. On February 3, 1945, the Bilibid prisoners heard the sounds of small- arms fire. The next day, elements of the American 37th Infantry Division stumbled on Bilibid and liberated it. Almost three nightmare years were over at last.

“The Love Life of a China Marine”

Good food and medical care did wonders, and Soochow and his human friends began to recover from their ordeal. Soon, the former POWs were ready to be transported back to the States. However, after going through so much, Soochow was almost stopped by the most formidable enemy of all—military regulations.

Soochow was on the dock when a young Navy lieutenant flatly refused permission for him to come aboard. The Marine ex-POWs protested, telling the lieutenant who the dog was and what he had experienced since Shanghai. The Navy man was sympathetic and referred the matter to his captain. “Regulations are regulations!” was the answer, so Soochow was sent back. But the young lieutenant privately assured the ex-POWs that something would be worked out.

Things were worked out, indeed. Instead of a long sea voyage, Soochow was given the VIP treatment and sent home by air. He was accompanied by Technical Sergeant Paul “Pappy” Wells, an old friend from the Shanghai days. The U.S. Army transport airplane landed in San Francisco in March 1945. It was the first time Wells had been home since 1938. After the plane taxied to a stop, Wells and Soochow stepped out to be greeted by personnel from the Mare Island Navy Base.

It was said that Soochow wore the remains of his old Shanghai uniform, the Pfc. stripe still visible amid the rags. After a proper welcome the pair was sent by train to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at San Diego. Wells and Soochow parted company, but the dog stayed on to become the depot’s mascot.

He was now a corporal, all POWs being given a one-grade promotion, but the dog was still the same old Sooch in many ways. Soochow would post himself by garbage cans near the mess hall, and woe betides any boot who tried to throw away food. The corporal would bark and carry on, alerting the drill instructors to the recruit’s transgression.

Depot personnel tried to set Soochow up with a blind date, but the rendezvous was not very successful. His “girlfriend” was supposed to be a white-haired mongrel WAF called Stormy Weather. They posed for pictures, a Marine cap perched on Soochow’s brow, but after the photo session the pair did not hit it off. In fact, the two dogs disliked each other and soon got into a fight. As one viewer put it, “There goes the love life of a China Marine!”

Soochow the Sergeant: Always Faithful

Soochow’s heroism was officially recognized, and he was promoted to sergeant. The citation read: “For exceptional ability, sound judgment, aggressive initiative, and unwavering devotion to duty in carrying out his obligations as Corporal, canine … Corporal Soochow is hereby promoted … to the rank of Sergeant, Line, United States Marine Corps.”

The newly minted sergeant received a rare honor when the whole depot turned out and paraded. The date was October 29, 1946, and it was the first time a mascot was given such a ceremony. It was well deserved. Presumably Sooch also had cleared immigration. He was Chinese, after all, and no doubt was also a U.S. citizen by virtue of his service in the military.

Soochow enjoyed his years at San Diego, where he was honored and loved as a true veteran. He probably followed his Shanghai routine, as far as time and altered circumstances would permit. But the years were catching up with old Sooch, and he probably was not as fast while chasing cats as he had once been. His body probably also suffered from the long-term effects of imprisonment. Soochow was tough, but his life as a POW had taken its toll. There is no way of knowing how much longer he would have lived without the Philippine years.

Sergeant Soochow, United States Marine Corps, died on April 21, 1948. He was 11 years old, and with his passing another link to the old 4th Regiment and Shanghai was gone. Yet, the memories of the dog, the regiment, and its colorful duty station have been kept forever green by the telling and retelling of Soochow’s amazing story. Here was one Marine who lived up to the celebrated motto of the Corps: Semper Fidelis—always faithful.

Eric Niderost is a frequent contributor to WWII History magazine. He writes from Hayward, California, where he is also a college professor.

All for the love of a dog. The American idea of a “family” pet brings a small amount of normalcy to their lives and piece of home to keep in their thoughts. God bless his Marine Corp buddy’s who cared for him, and his strong, valiant and devoted heart. I hope they have a memorial statue of him.