By Frank Jastrzembski

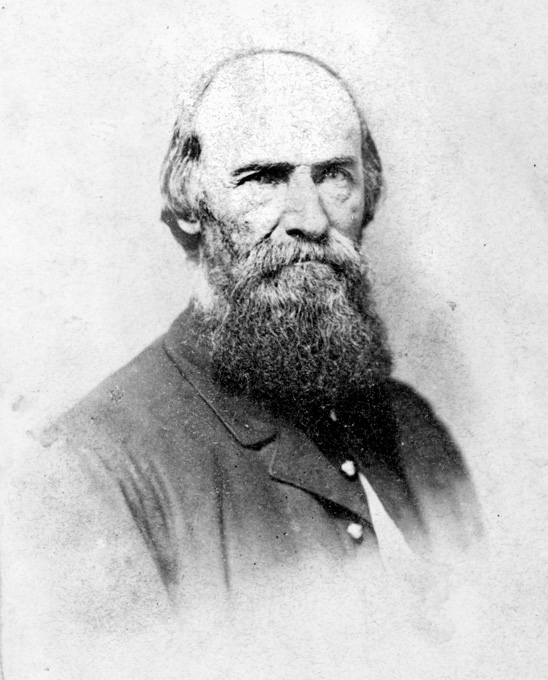

“A soldier in every phrase of the term, able and skillful, on many a bloody field he demonstrated his ability and courage,” Brig. Gen. Richard W. Johnson wrote in glowing praise of Brig. Gen. August Willich in January 1866. Johnson could vouch for this, having served as Willich’s superior during the American Civil War.

“[He] is a theoretical and practical soldier,” wrote Johnson. “He has made the science of war his study and there are few men his equal in military matters. He is thoroughly conversant with the military and political campaigns of Europe. He looks well to the interests of his men.”

This German exile-turned-American general placed his life on the line for his adopted country. To Willich, winning the Civil War was not just about keeping the Union together, but more importantly it was a war for social equality: crushing the institution of slavery, proving that his fellow Germans deserve a rightful place in American society, and improving the lives of the working class. Red communism flowed through Willich’s veins, but he donned federal blue in his crusade for the downtrodden. “I fought for liberty in the old country,” he declared in May 1863. “I fight for liberty in this country.”

Johann August Ernst von Willich was born on November 19, 1810, in Braunsberg, East Prussia. His father, Johann George, a captain in the 10th Hussars died in 1814, leaving Lisette, Willich’s mother—a Polish stage actress—a widow to care for two young boys. There were rumors that the younger boy, August, was the illegitimate son of a Prussian royal prince, and in his adolescence, he would declare, “Look into my eyes and you will see the Kaiser,” insinuating he was of royal blood.

August entered the cadet school at Potsdam at the age of 12 in 1823. Three years later he was accepted into the Germany Military Academy in Berlin. At the age of 18, Willich was commissioned a second lieutenant. By 1844 he had risen to the rank of captain. His superiors transferred him to a remote outpost due to his radical political views. Suffused with discontent, he resigned his commission in November 1847.

The year 1848 saw the rise of liberal and nationalist uprisings throughout Europe, ranging from Berlin to Naples, the direct result of the revolutionaries having forced France’s King Louis Philippe to abdicate in February. Rebellion broke out two months later in the Grand Duchy of Baden after the government rejected several liberal reforms. Willich joined with the revolutionary forces and served as a senior officer. Ultimately, the revolutionaries were defeated by the government forces as a result of their lack of coordination and poor leadership decisions. Willich and his beaten soldiers fled to the Republic of France and waited in exile for an opportunity to return to their homeland.

In 1849, Willich participated in the Palatine uprising with Franz Sigel, Carl Schurz, and other so-called “Forty-Eighters” who would rise to the rank of general during the American Civil War. This uprising failed just as the revolt in the Grand Duchy of Baden had. Willich fled and ultimately settled in Great Britain.

While in England, a confrontation with Karl Marx led German proletarian revolutionary Conrad Schramm to challenge Willich to a duel, which the two fought in Belgium. Willich’s bullet grazed Schramm’s head but fortunately did not kill him. Willich, with his future uncertain, left for New York City by steamer in January 1853.

When civil war broke out in America eight years later, Willich enlisted as a private in the all-German 9th Ohio Infantry but was later appointed as the regiment’s adjutant. His military background allowed him to whip the green volunteers into disciplined soldiers and he was soon commissioned a major.

Governor Oliver P. Morton specifically selected Willich to be colonel of the 32nd Indiana Infantry in August 1861. At the Battle of Rowlett’s Station in mid-December, the regiment stubbornly fought off a superior Confederate force under the command of Brig. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman, earning acclaim for both the Indianans and its colonel.

At the close of the first day of fighting at Shiloh on April 6, 1862, Willich’s regiment arrived as part of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of Ohio to aid Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s beleaguered Army of the Tennessee. Before leading his Hoosiers into battle the next day, Willich gave them a rousing speech. “Little children, today decides the fate of America,” he said. “If we are beaten today everything is lost; let us do our duty as a free man does.”

His single regiment met Brig. Gen. Sterling A.M. Wood’s brigade, which had been ordered into action as part of Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard’s effort to punch through the Union line. Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace watched in awe as Willich, mounted on horseback, coolly steadied his regiment as shot and shell tore left and right around him.

“What he said I could not hear, but from the motions of the men he was putting them through the manual of arms, notwithstanding some of them were dropping in the ranks,” recalled Wallace. “Taken all in all, that I think it was the most audacious thing that came under my observation during the war.” A spent ball struck Willich in the chest, but his wallet stopped the bullet, leaving him with only a few broken ribs.

Willich was promoted to brigadier general and given command of the brigade his regiment was part of that summer. At the Battle of Stones River, fought on December 31, 1862, the newly minted general fell into enemy hands after his horse was shot from under him. Willich spent several miserable months at Richmond’s Libby Prison before being exchanged in May 1863.

While imprisoned, Willich devised a tactic to increase the rate of fire in his brigade, which he termed “advance firing.” The maneuver, which Willich implemented with his troops, called for the first rank to fire and then stop to reload while the other ranks advanced a few paces, fired their rounds, and allowed the next rank to advance.

Adopting this maneuver gave Willich’s regiments unprecedented continuous firepower. Willich first implemented this maneuver in June 1863 at Liberty Gap, which was a corps-sized battle in which the Union prevailed as part of the Tullahoma Campaign. One captured Confederate soldier who experienced the steady fire was shocked by the heavy fusillade. “Lord Almighty, who can stand against that?” he exclaimed. “Four lines of battle and every one of them firing?”

But it was at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19, 1863, where Willich’s First Brigade of Johnson’s Second Division of Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook’s XX Corps really shined. Johnson’s Second Division, which included Willich’s brigade, came to the support of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’ XIV Corps.

Willich, anchoring Thomas’ right flank, ordered a bayonet charge into Brig. Gen. John K. Jackson’s brigade of Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham, driving back the exhausted Mississippians and Georgians. Brig. Gen. George Maney’s regiments came to Johnson’s aid, but Willich formed the 49th Ohio Infantry and 32nd Indiana Infantry into four lines and gave the order to “advance fire” to meet the threat. The Confederate defenders were driven back by the combined forces of Willich’s First Brigade and Colonel Joseph Dodge’s Second Brigade.

Willich’s brigade advanced so rapidly that it outpaced Colonel Philemon P. Baldwin Third Brigade on its left, whose advance was hindered by dense foliage. The Confederates counterattacked, outflanking Baldwin’s command. Willich, in an attempt to inspire Baldwin’s men, had his horse killed. But ultimately, Baldwin’s Indianans, Kentuckians, and Ohioans held their ground.

At 8:00 pm more than 5,000 men of Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne command launched a violent assault on Johnson’s Second Division. Colonel Baldwin fell dead while trying to rally the 1st Ohio Infantry. His brigade retreated, which in turn caused the retreat of Willich’s regiments. Willich rallied his soldiers 300 yards from their original position, where it continued to take fire from three different directions. Nonetheless, the stubborn brigade stayed put that night.

The collapse came when Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans ordered Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s First Division to move and close a gap on the left and link up with Maj. Gen. J. Joseph Reynolds’ Fourth Division. Rosecrans had no idea that he was trying to close an imaginary gap.

Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s crack troops happened to be striking at the perfect point to take advantage of the absence of Wood’s division, leading to the collapse of the Army of the Cumberland. Willich covered the retreat of Maj. Gen. John M. Palmer’s Second Division of the XXI Corps and Reynolds’ Fourth Division of the XIV Corps at Kelly Field.

His five regiments helped to stave off total annihilation, fighting off numerous enemy assaults from four different directions. For this act, Willich’s soldiers earned the sobriquet “Iron Brigade of the Cumberland Army.” Yet they paid dearly for it: Willich’s brigade suffered 539 casualties, the equivalent of one-third of its number. After the battle, Thomas praised Willich’s performance, who he said, “most notably sustained his reputation as a soldier.”

After the Army of the Cumberland settled into the city of Chattanooga and Rosecrans was relieved, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant assumed command of the Military Department of the Mississippi and began to shore things up in the Western Theater.

Willich was shot in the upper right arm on May 15, 1864, in the Battle of Resaca in north Georgia while making observations from a parapet. He could hardly grasp anything with his right hand and never regained the full strength of his arm. It would be the general’s last engagement of the war.

On October 21, 1865, Willich was brevetted major general for his service during the war. He was mustered out in January 1866. Several individuals recommended that Willich be commissioned a colonel in the regular army. “His military experiences and capacities are too valuable to be lost to the country by his retirement to civil life,” wrote Governor Morton. “His retention in the service besides being due to his high character, eminent abilities, and distinguished services, would be a compliment to our German citizens and would be received as a high mark of appreciation.” However, Willich’s post-war army career never came to fruition.

Willich was elected auditor of Hamilton County in 1867, but shortly after his term ended in 1869, he returned to Germany. He offered his service to the Prussians during Franco-Prussian War, but Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke turned him down.

Willich returned to the United States, humbly living out his days in St. Marys, Ohio. August Willich died of natural causes on January 22, 1878. As many as 2,500 citizens came see him laid to rest. Among those in attendance were veterans of the 9th Ohio Infantry, 32nd Indiana Infantry, and other units. They all sought to show their deep respect and appreciation for the hero of two nations, and they accompanied him one last time as he was laid to rest in Elmwood Cemetery.