By Tim Brady

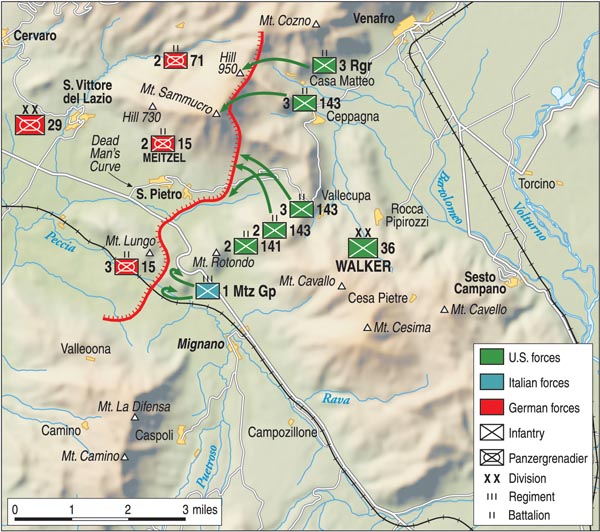

After sweeping through Sicily in the summer of 1943, Allied forces invaded Italy in September. The American Fifth Army landed at Salerno and moved up the peninsula through Naples that fall. General Mark Clark’s forces stalled three months into their campaign, in the shadow of Monte Sammucro on the edge of the Liri Valley. It was early December. A month’s worth of rain and snow slicked the surrounding hillsides and made a muddy mire of the valley.

The German line ran from the top of Sammucro down through the village of San Pietro and across the valley. It was formidable and ensconced; the mountain was almost 4,000 feet high and steep. The Via Latina running past its base was the only road from southern Italy to Rome. And Rome was the goal of Mark Clark and the Fifth Army.

Clark chose the 36th Division, the “Texas” Division, to lead the assault. Among those heading up the mountainside at Sammucro in the middle of a chill and wet December night was a young captain from the 36th’s 143rd Infantry Regiment named Henry Waskow. Quiet, dedicated, effective—a good soldier from a small town in Texas, but not the sort who would stand out in a crowd—Waskow did his job and did it well.

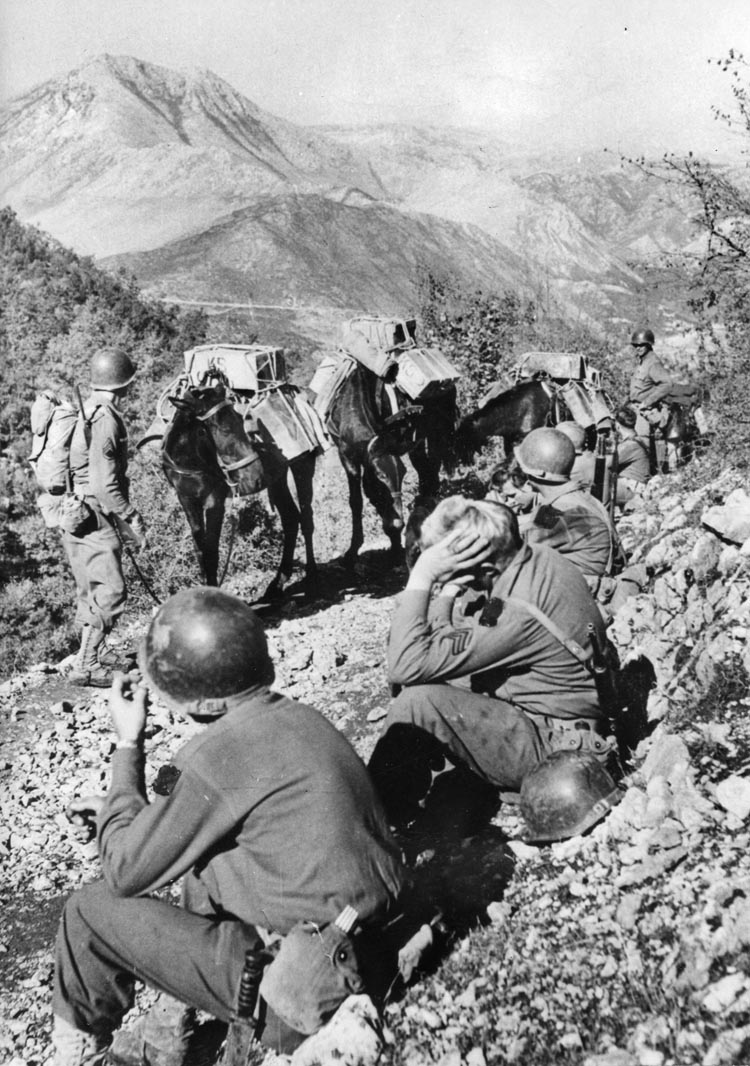

History might have totally passed him by but for a little man in a knit cap, smoking cigarettes down at the foot of Sammucro. Ernie Pyle watched the supply mules head up the mountains with provisions; he watched them come back down with American soldiers draped over their backs. Pyle had seen a lot of this already in the war, but something about the struggles at San Pietro, something about Henry Waskow, moved him in a way that he hadn’t felt before.

Just after 5 pm on December 7, 1943, 1st Battalion, under the command of Lt. Col. William Burgess, began the long climb up the eastern slope of Monte Sammucro.

Breaking off and heading to the right of the 1st was the 3rd Ranger Battalion, whose assignment was to take Hill 960, slightly to the north of Sammucro.

It was no easy task ascending the mountain in the dark. In the best of circumstances—daylight, dry, sunny weather—it was a three- or four-hour climb. This night in darkness and fog, it would take several hours more.

In the lead for Company A was commanding officer, Lieutenant Rufus Cleghorn of Waco, Texas, and the Baylor University football team. Companies C and D were right behind, with Waskow’s Company B bringing up the rear and providing supply-transport assistance.

The order given to Cleghorn by battalion commander Martin was a no-ifs-ands-or-buts: “Young man,” he was told, “I want combat troops on that mountain by eight o’clock in the morning.” So Cleghorn led with a determined pace. The mule trails on the slopes disappeared along with the scruffy pines at the tree line, leaving the men of Company A and the units following to continue by any means necessary, which at times meant on their hands and knees.

There were moments, as well, when the climb grew so steep that the infantrymen were forced to chin themselves over sharp rocks; at other times, ropes were necessary to haul themselves upward. Company B was tasked with bringing supplies upward from where the mules left off at the tree line, which meant they were carrying ammo over these same rocks and ridges.

The fact that they were approaching the summit from the far right flank encouraged Colonels Martin and Burgess to believe that the 1st Battalion would be striking with an element of surprise against the Germans, whose focus was known to be toward San Pietro and the valley floor to the southwest of the peak. There was even some hope that the summit might be lightly, or not at all, occupied by the Germans.

That hope was quickly dashed, however. It turned out that the mountain peak was indeed manned by panzer units, but they were, in fact, surprised to see American troops coming at them from the east. The 1st Battalion swarmed over the crest of the mountain, heaving grenades at pockets of Germans as they climbed. A fierce firefight followed the enemy’s realization that they were being attacked.

The battle quickly grew so intimate that the Germans used loose boulders as weapons, trying to sweep 1st Battalion troops off the mountainsides by knocking them over with rolling rocks. Cleghorn’s stout voice helped guide his men toward the top, and like the Germans, he, too, began hurling rocks at the defenders—along with hand grenades and epithets.

The measure of surprise had its effect. The Americans made steady progress, and at 6 am, members of Company A, led by Cleghorn, reached the top of Sammucro, just as Colonel Martin had ordered and hoped. A little after 9, platoons from Companies C and D joined Cleghorn and Company A in the lead and poured more fire on the panzer forces at the summit, but a scribbled message to command said that “ownership of Objective G [the summit] was still in question.”

The 1st Battalion continued to fight and an hour later sent another message down the hill. While the Rangers on Hill 905 to the right flank were “having a pretty stiff fight …. We are in supreme command of 1205.” Two hours after that, just after noon, the 1st was holding 12 German POWs on top of the mountain and catching its breath from 18 hours of hard climbing and hard fighting.

Hard fought and hard won: it was a good way to start the battle for San Pietro and the Liri Valley. Not everyone involved would have such success.

Wearing feathered caps to match their Alpine uniforms, two battalions of the 1st Italian Motorized Group set out that same morning from Mignano. A sharp American artillery cascade had preceded their move onto the hill, which occurred in the midst of the subsequent smoke and a fog that settled down in the valley. With vengeful spirit the Italians started to climb the ridges to the peak of Monte Lungo boldly shouting challenges to the German troops above. Unfortunately the Italians had failed to send out any recon the night before, and now blinded by the weather and smoky haze, they moved in tight units directly into a blast of German machinegun and mortar fire. The enthusiasm of the Italians was short lived as the devastating fire quickly took a heavy toll.

A company of the 141st up on nearby Monte Rotondo set up firing positions to back up the Italians and discourage the Germans from pursuing their advantage. But by noon, the 1st Italians was in a sorry condition, having already lost more than half of its original 1,600-man strength, most of whom were missing, having hightailed it off the mountain.

Down below San Pietro, the 2nd Battalion of the 143rd was having a rough time of it as well. From their position on Monte Cannavinelle, troops of the 2nd had headed out in the early morning darkness, moving down the 3,000-foot mountain, where they’d been stationed in preparation for this attack. They headed toward the eastern slope of the Sammucro, just above San Pietro, but even their first steps were troublesome.

Unlike rocky Sammucro, Cannavinelle was blanketed in mud, which made footfalls treacherous. To prevent frantic sliding down Cannavinelle to the line of departure in the valley below, troops grabbed at roots, branches, tree trunks, anything that would catch their fall, all the while loaded with battle gear that included machine-gun belts, mortar shells, boxes of hand grenades, and bazookas.

A bridge down below served as the point of departure, and the first troops of the 2nd—Companies E and F—set out from there at 6:20 after a booming display of “outgoing mail” from American artillery. Just 200 yards into their trek into the valley below San Pietro, they hit a line of barbed wire backed by well-placed pillboxes armed with automatic weapons. Mines were also liberally laid in the field. All of this stopped the battalion in its tracks and allowed German mortar and artillery fire to zero in.

Efforts were made to move the troops back a hundred yards so that American artillery could safely pound the pillboxes; but when the guns started blasting the German posts, they did so to limited effect. The only openings in these fortresses were narrow slits designed for small arms fire, which served as great protection for the panzer troops inside. Meanwhile, the artillery pounded away, creating an enormous echo chamber in the valley that reverberated with deafening explosions.

Colonel Martin sent the 3rd Battalion swinging out to the right of the 2nd in an attempt to flank the German line. Company L arced wide to the northeast and headed back to the west, straight at San Pietro down the Venafro-San Pietro road. Six hundred yards into its westward advance it hit the same mix of mines, mortars, wire, and pillboxes that had stopped the 2nd. One Company L staff sergeant put it plainly, after all their efforts, “The Germans still held the high ground and had clear view of the valley.”

Martin committed two more companies of the 3rd Battalion, I and K, into the fight to the right of the rest of the battalion. “Texas cowhand and rebel yells pierced the air,” according to one eyewitness account. “A German colonel leading his men was cut to pieces by a BAR. Other Jerries plopped down in a heap behind. The ‘spang-spang’ of the trusty MI’s and rattle of our .30-caliber machine guns and BARs became more intense. Brave men were dying.” Again, however, the attack across what was about to earn the nickname “Purple Heart Valley” made limited headway.

About 400 yards into their trek, Companies I and K were told to hunker down and dig in. Private Jack Clover and his digging buddy Jabe Curry chose the front edge of a gulley and quickly started to spade out a foxhole. They were waist deep in the project and hustling to finish when a giant shell landed nearby, burying them in their own hole. Clover clawed his way out of the would-be grave and waited a moment for Curry. They exchanged terrified glances, knowing there was no place for them to go.

Up on top of Sammucro, the situation was far better but about to get dicey. The Germans were not about to cede the summit of the hill so easily to the Allied advance. The first counterattack began at 6:30 the next morning and lasted for more than half an hour. Another assault hit from all sides at 8:10, wounding Lieutenant Roy Goad, among others. A third came just after 10, and yet another hit just after noon, this one seriously wounding Lt. Col. Burgess, who had to be evacuated and replaced by Major David Frazior.

The commander of Company C, Captain Lewis Horton, attempted a probe of German positions to the west toward San Vittore with the idea of aiding the 3rd Rangers, which were still having trouble taking Hill 960. Under heavy fire, he’d taken his platoon leaders to a post where they had better vantage of enemy defenses. While devising a plan of attack, a sniper caught Horton, killing him instantly.

And so it went all day on December 9. Counterattacks continued to a number that was either seven or eight—it was hard, under the circumstances, to keep track. German prisoners later explained that they had been ordered to retake the mountaintop at all costs, which meant the nature of the fighting was often savage.

Platoon leader Willie Slaughter, Company B, saw one of his men engaged in a peek-a-boo style shootout with a German sniper. “They were crawling around in the rocks and every time one would stick his head out, the other would start shooting. They looked like a couple of lizards crawling in those rocks.” From his “ringside seat” Slaughter could hear his man shouting, “Where is the son-of-a-bitch?”

Using mortars that had been painfully hauled up the hill the day before, mainly by Waskow’s company, the 1st Battalion was able to use its position to assist the 3rd Rangers on Hill 960. The Rangers were finally able to surmount the hill and thus relieve some of the fire heading up toward the 1st Battalion from the neighboring mountain.

As 1st Battalion battled counterattacks and assisted the 3rd Rangers, it also began to probe down the mountain toward San Pietro and San Vittore. As it did, the lines between Germans and American got crossed and intersected, particularly down the northwest side of the mountain toward San Vittore.

Captain Jalvin Newell, on the side of the mountain with three companies of the 143rd, had his phone lines cut as he was trying to reach Lieutenant Richard Burrage, communications officer for the new commander, Major Frazior, who was at the top of Sammucro. Newell needed to pass on info and questions to Frazior. Companies A, B, and C were rapidly losing men. Should they head back up to the summit from their position or stay and fight down the hill?

To relay the communication, Newell resorted to a code that would be known only to Texas boys: he used references to Texas towns whose first letter coincided with Companies A, B, and C. There was talk about mail and numbers of letters addressed to each of the towns. It took a while for Burrage and Frazior to figure out what the hell Newell was saying.

Finally they realized that he was indicating the Germans were pressing hard. The numbers of letters to each town indicated the dwindling numbers of men in each company. Should they come back up to the summit? Burrage radioed back instructions—not necessarily happy news: Newell was asked to keep the companies in place and hold on.

Meanwhile, the wounded on the hilltop began to stack up. More than 40 members of Company A were killed or put out of action in the two days of fighting; another dozen members of Companies B and C suffered similar casualties.

Some walking wounded made it down the mountain, although hounded by artillery all the way, and were eventually transported to Naples.

Many others were unable to make it down unassisted, and the perils of descending the mountain were nearly as great as heading up. Litters were carried over the same steep cliffs, inclines, and jutting rocks that were climbed on hands and knees and with the aid of ropes on the way up.

The wounded went down first, carried by others from their own units, who struggled against the hillside as they listened to the moans and cries of their comrades, essentially helpless to make the journey any easier. Still better than the dead, who came down when it was convenient, and then, most often, only to the way station at the tree line, where bodies covered in tarp and roped tight to the litters began to accumulate.

Given all of the attacks and counterattacks, supplies of ammunition quickly began to dwindle atop Sammucro. So did food, water, blankets, boots, and any sense of comfort. On the summit, snow took the place of rain. The ground was all rock, which made digging foxholes impossible; cold boulders and hard crevasses served as cover instead. Even without standing in muddy holes, boots remained constantly damp and feet were frozen. Trench foot was endemic.

Supplies going up the hill followed the path of 1st Battalion. There were about 80 mules in the train, led by Italian skinners who dressed, as had the Motorized Italian Army unit that had charged Monte Lungo, in Tyrolean gear, including feathered hats. The mules were packed during the day and set out toward the mountain only after dark.

According to Ernie Pyle, who had joined a 143rd supply unit a few days earlier, typical loads were 85 cans of water, 100 cases of K rations, 10 cases of D rations, about 1,000 rounds of mortar shells, a radio, telephones, four cases of first aid kits and plenty of sulfa. Also in the packs were cans of sterno, heavy combat uniforms, and what Pyle called the “most tragic cargo,” the mail, which went up every night in what would turn out to be a long stay on the mountain.

Sometimes it would be received by dead men; sometimes by the wounded who were already heading down the mountain; sometimes it would be received with more than a little irony, as in the case of one corporal in Company B, who got a Christmas necktie in a package while up on Sammucro.

The supply unit worked out of an olive grove near Venafro, and there Pyle shared quarters with about 10 members of the unit in an old cowshed. Private Lem Vannata, who worked as a supply clerk at the post, remembered his arrival: An older man, relatively speaking, wearing a war correspondent patch on his shoulder and skinny as all get out. An officer told Vannata who the man was and said, basically, to leave him alone, that Pyle would contact them if he wanted to talk.

His name, of course, was recognized by everyone in the theater, including Vanatta, who let him be until one day Pyle caught him taking a nip from some bootlegged liquor that Vannata had stored near the dump. Turned out Pyle was just interested in taking a snort himself, and there began a daily ritual between the two that lasted for the length of Pyle’s stay.

As noted, the Italian mules were unable to negotiate the full 4,000-foot climb up the mountain. It was just too steep and nasty. In fact, they were only able to haul about a third of the way up its sides. A whole column of assistants from supply, transport, and HQ stations down below would accompany the train each night, and when the mules gave out, the men would take over, strapping the loads to their backs and humping them toward the battalion above.

That battalion was also forced into carrying its own supplies up the mountain. Carefully slipping down the mountainside after days battling Germans up above, they would meet the ascending collection of cooks, truck drivers, and clerks who were hauling from the point where the mules gave out, and proceed to lift the cargo up to the summit, bringing their own K rations and mail to the rocky fortress on Sammucro. Company B had this assignment at the start of its time on the mountain.

Pyle, too, climbed up Sammucro, as much as anything else, to see the effort involved. He marveled at the strength of one packer, who could make it to the top with a full can of water in two and a half hours. Pyle’s guide was a member of 1st Battalion who had been at the top fighting and was now supposed to be resting below. Instead, he was escorting Pyle on feet so sore from blisters that that he walked only on his toes to save his sensitized heels from rubbing against the hard rock.

Pyle ran into a Signal Corps team of movie photographers as they bumped into a trio of German POWs being escorted down the hill by a lone GI. The Signal Corps camera operators asked the infantryman if he would go back up the hill 50 feet and come back down the trail so that they could get the shot of the POWs in action, descending down the trail. In the midst of war, reality was thrown in reverse to be captured on film.

The Germans seemed only temporarily confused about what was happening. Soon enough they understood the filmmakers’ needs and not only willingly repeated their march down the hill but took time to fix their collars and straighten their trousers.

Pyle also happened across Emmett Allamon, a regimental surgeon from the 36th, at the medical station housed in an old stone building at the top of the mule trail. Pyle’s arrival there prompted the doctor to break out a saved bottle of bourbon that had been waiting for the right company.

Pyle later wrote his wife about the visit, telling her that he and the doctor were talking in the loft of the station when German artillery started to land dangerously close, “but we felt so good by that time we didn’t even pay any attention.”

He and Allamon were talking about the “mental wreckage” of war—those soldiers broken by the dangers and stresses of battlefield. The doctor took a pretty tough stance, saying that he thought the root cause for the number of breakdowns on the front line was societal, that too few American children were being given opportunities for self-sufficiency; and as a result, they crumbled now when faced with adversity. They simply hadn’t faced enough adversity before. He thought ex-newsboys were best suited for war, because they’d been raised from early in life to fend for themselves.

Whether this conversation was an offshoot of what had happened in Sicily with George Patton and the slapping incidents, Pyle does not say. That story had finally been leaked by the press to the American public, and the subsequent outcry was making headlines. In any case, Pyle was much more sympathetic to the phenomenon than the doctor. “The mystery to me,” he wrote, “is that there is anybody at all, no matter how strong, who can keep his spirit from breaking in the midst of battle.”

A German counterattack on December 11 left Rufus Cleghorn wounded on Sammucro. He joined a growing number of officers and staff sergeants from Company A who had been knocked out of action. Aside from losing Captain Horton, who was killed by sniper fire, and Lieutenant Goad to a wound, Company C was down two more officers and four staff sergeants by December 12. Waskow’s Company B, which, because of the time spent hauling supplies was out of the most intense action, had lost only one officer killed in action.

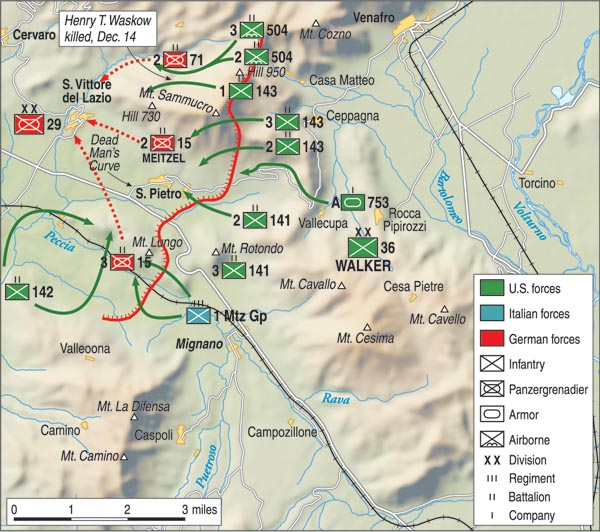

Four days into the action, the battalion was down to half strength, with just 340 soldiers up on the ridge. The loss of men prompted II Corps commander Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes to reinforce the 1st on December 11 with the 504th Parachute Battalion.

Meanwhile, in the valley, the Germans continued their tight hold over San Pietro. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions remained stuck where they’d been since the attack on December 8—about 1,000 yards shy of San Pietro. The Fifth Army might be holding Monte Sammucro, but it couldn’t go farther without access to the Liri Valley—and the Liri Valley was controlled by the German forces surrounding San Pietro.

The pressures for moving on quickly mounted. On Mark Clark. On 36th Division CG Fred Walker. On all their units. Already it felt like the army was stalled again, well south of Rome. It hadn’t yet breeched the first of the Winter Lines; and the second, stouter line, the Gustav, that ran through Cassino, still awaited. A plan for forcing the valley open was needed and Clark had one in mind. He bounced it off of Keyes and Walker—Walker was not enthused: How feasible was it, Clark wanted to know, to mount a tank assault against the village?

Not very, Walker thought. A recon report suggested a number of formidable obstacles. Not only was the ground in the valley saturated by the incessant rain, but a series of streambeds and gullies ran along the southern base of Sammucro surmounted by a number of small bridges and culverts that could be easily destroyed by German artillery.

Most daunting, however, were the terraces that fronted San Pietro to the south, east, and up the mountainside. These were in the neighborhood of three to seven feet in height, all shored up by rock walls insurmountable to tanks. In addition, the snaking mule trails that led from one level to the next were simply too narrow for tanks to negotiate.

Nonetheless Clark, supported by Keyes, argued that heavy armor had made gains under more stressful circumstances and time was wasting. If it wasn’t tanks doing the job, what would it be? In a few days, the 36th would be one full week stuck at San Pietro—one more week in which no progress had been made toward Rome.

December 15 was the day chosen to mount the next assault against the village, and tanks would lead the way in a two-pronged attack: a column of tanks would roar up the valley, sweep around the southwest corner of Monte Sammucro, and head straight for the village in a frontal assault. Meanwhile, forces from Sammucro would descend down the ridges to attack San Pietro from the hillside; and the 2nd and 3rd Battalions would attack simultaneous to the tanks from the south and southwest of the town.

In preparation for the assault, the order came from Major Frazior on December 13 for Company B to edge out to the “nose of Sammucro”—the area of the summit on its west end overlooking the Liri Valley—to get into position to head down the summit by the next evening. Waskow’s company was to take the lead in the attack on San Pietro from above, and to do so it needed to be on the west edge of the mountain, pointing down.

With a few hours of relief under its belt, Company B headed back up Sammucro from the east side of the mountain in preparation for the battle. On the way up, it ran into Company I coming down the hill.

It was not a moment for lingering reunion. In low voices, the soldiers swapped stories about what was happening up above and what was happening down below; who from their neck of the woods in Texas had been wounded, and who had been killed. There were even some laughs about the guy from Company B who had got a Christmas tie while up on the mountain. Then off they trudged in their opposite directions.

Riley Tidwell’s feet were a mess. His trench foot had degenerated to the point where he could no longer put pressure on the soles of his feet, so covered in sores were they. Instead, he dug into the hillside with his heels, almost backing up the mountain. Down at the aid station, before Company B set out that day, Tidwell made coffee for his captain and pulled out his can of sterno.

In the usual way, he stuck a piece of bread on the wire hangar that he always tucked into his kit for just this purpose. He proceeded to make toast for Waskow and listened as he told him once again how, when the war was over, he was going to get himself one of those fancy new pop-up toasters. “Smart Alec toasters,” he always called them.

He also asked Tidwell about his feet and Tidwell gave his captain an honest picture of his circumstances. Truth be told, he was having a hard time walking. He mainly had to stay on his heels. Waskow decided to send Riley back down to get treatment. What good was a runner who couldn’t run? Tidwell heeled himself down to the aid station on the mountainside, where medics gently took off his boots, cleaned his feet, and wrapped them in gauze. It felt like heaven by comparison to how they’d been aching before. Tidwell felt chipper enough to rejoin Waskow and the company as they were still ascending Sammucro.

Sergeant Willie Slaughter’s platoon had broken off on a separate patrol to the west, to nearby Hill 570, where they were to make contact with a unit from the 504th Parachute, the unit that had initially served as a replacement unit for the 1st Battalion. As they walked the ridgeline, Slaughter spied a pair of heads poking up over a rock along his path. He inched his way forward, saw one of the heads turn in his direction, caught the shape of a German helmet and then the sight of the panzer rifleman turning a machine gun in his direction. Along with the rest of the platoon, Slaughter dove for cover as the Germans opened fire.

They had stumbled on a German observation post. Cooly, Slaughter lobbed a grenade in the direction of the two soldiers. Meanwhile, Slaughter’s old football buddy from Mexia High, Sergeant Jack Berry, was about to jump out from cover and help a member of the platoon who had been caught in the first burst of fire. Slaughter warned him against it, but Berry was gone before the words registered. Jack Berry was struck with gunfire and killed as he crawled over the rocks to his comrade.

Slaughter and the rest of the platoon settled in for a firefight that would last for a couple of hours. In the end, the group from the 143rd would kill seven Germans, wound seven more, and capture 13 members of the 15th Panzergrenadiers. From these POWs, G-2 was able to learn that artillery had knocked out the German command post down in San Pietro days earlier, that replacements coming into the village were generally older troops, 30 and 40 years old, and that about 120 infantrymen were now in the town. All encouraging news.

The rest of Company B heard the small-arms fire and grenades of Slaughter’s platoon as they moved along the summit of Sammucro. It was now deep into the evening on a misting, foggy night. As the company reached and then inched out over the “nose” of Sammucro, Waskow commented on the murky dark and the landscape: “Wouldn’t this be an awful spot to get killed and freeze on the mountain?”

With Tidwell and his first sergeant, John Parker, another Mexia man, Waskow eased down over the west edge of Sammucro. They’d gone just a few steps more when a shell came whistling in. Waskow picked up the sound of the screaming round a split second before Tidwell and gave him shove, hollering at his runner to hit the ground. Tidwell did just that, as did Parker.

Waskow was too late. The shell burst above him and shrapnel tore into his chest, shredding his heart and lungs. He was dead in a gasp.

It was a bad day for Company B on the mountain. The artillery fire continued intensely all morning on December 14, sweeping the mountaintop and adjoining ridges. There wasn’t much protection among the rocks when the German guns zeroed in.

The company continued down the southeastern face of Sammucro toward San Pietro, moving in conjunction with 2nd and 3rd Battalions, which proceeded on a line from the slopes to the west of San Pietro, basically where they had left off a few days before during the first assault on the village.

Company B got pinned down in a German counterattack and was asked to hold the position. All day long it fought and got punished for the effort. Both of the remaining officers in Company B—two first lieutenants—were killed; First Sergeant Parker was eventually wounded. Two staff sergeants, including Jack Berry, were also killed. Another Mexia man, Private Floyd Durbin, was dead, and yet another Mexian, Hulen Tackett, was wounded. Scores of replacement soldiers—those who had arrived in October from all over the country—were also killed and wounded.

Company B’s casualties were now comparable to Company A’s and C’s. All units were down to about 30 percent of full complement. More than 800 of the men who’d climbed Sammucro on December 8 would be dead or wounded before the month was over.

Back where Henry Waskow lay, it was Tidwell who checked for signs of life and saw none. It was Tidwell who found Waskow’s kit with its Bible, its postcard book from Capri meant for sister Mary Lee, with its last letter written and folded on a piece of rough field paper. It was Tidwell who helped pick up the captain and took him down to the head of the mule trail.

There at the station, he lay Waskow down with the other dead bodies being collected. All were tied tight to their litters, waiting for their final leg off the mountain, when they would be draped over the sides of a mule and carried the last way down to the valley below.

Tidwell went back up the mountain and reported to Major Frazior that Company B no longer had any officers. The unit was leaderless down at its end of the mountain, overlooking San Pietro.

Tidwell had known Frazior from his duties as company runner, going back and forth from Waskow to battalion headquarters. Frazior knew Tidwell as well and noticed the condition of the runner’s feet. He asked Tidwell if he was capable of getting back to his unit. Tidwell guessed he was.

“Tell one of the sergeants over there to take charge until I get someone to the company,” Frazior told him, “and then take yourself down the mountain to have someone look at your feet.”

The company runner did as he was told, hobbling first to Company B, where he informed the first sergeant he saw of Frazior’s order, then back down the mountainside again to the aid station, where his feet were again wrapped in cotton gauze. This time, he proceeded all the way to the base of the mountain, where he found a shed occupied by exhausted members of the 36th, leaning vacant-eyed against the rough walls. He sat himself down and breathed hard and deep.

Sitting off by himself scribbling in a notepad was Ernie Pyle. He must have sensed that Tidwell wanted to talk and he slipped over in the tall man’s direction.

In fact, the lanky private did have some things that he wanted to say about the captain he had left earlier that day at the end of the mule trail on the side of Monte Sammucro. The man he had been trailing now for three and a half months through the mountains of Italy, and in North Africa before that, and Cape Cod, and all the way back to Camp Bowie in Texas. The man who drank his coffee, ate his toast, talked of smart alec toasters with him.

Pyle gently asked what had happened up there, and Tidwell told him how his captain had just died on the mountain.

“He must have been a fine man,” Pyle said.

Stunned by an awful day of war, feeling lucky to be alive and sick at what he had seen, Tidwell tried to frame his thoughts. “He was like a father to me,” was the best he could do.

As the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions began the assault on San Pietro, a battalion of the 141st was given the assignment of attacking the village directly from the south, on the left of the units from the 143rd. Monte Lungo, which had remained in German hands throughout the fight on Monte Sammucro, was to be attacked as well, by the 142nd.

Steaming at San Pietro on a winding line down the Venafro Road—from partway up the mountain to the east, down into the valley, and around the base of Sammucro—were Mark Clark’s tanks, which jumped off at noon on December 15. The road itself left little room for error. To the right of the tanks loomed Sammucro; to the left was a steep drop-off down the hill. The road was only the width of two small cars and from the moment they arrived in the valley, they were in open view of German artillery.

Eight tanks rumbled down the lane toward the village; eight more moved in conjunction with the 2nd and 3rd Battalions who were also sweeping around the mountain from the southwest in the wake of the first tanks. Neither component of the attack got very far. The Germans let the lead two tanks get near the town before they opened fire with antitank weaponry.

The panzer troops’ aim was directed on the trailing tanks in the first group and it was accurate. In a matter of minutes, two American Shermans were destroyed. They effectively blocked any means of escape on the narrow road for the lead tanks, which meant Wehrmacht antitank guns could wreck them at their own pace.

The next three tanks were stopped and disabled by mines. Each was abandoned by its crew, halting the progress of the remaining tanks, which were left to take fire from German positions around the valley. In all, seven tanks were destroyed, five were disabled, and only four made it back to their original assembly area.

The 2nd and 3rd Battalions, moving in behind the tanks, were not having much better luck. They were hit by a wall of automatic weapons, mortar, and artillery fire coming from San Pietro, Monte Lungo, and, most deadly, from the olive tree terraces that fronted the village.

General Walker’s assistant commander, Brig. Gen. William H. Wilbur, ordered Company E of the 143rd to swing around to the right of the tanks and up the hill to attack the village north to south from above. Late in the afternoon, Company L joined them. They got near to San Pietro but took such a severe pounding in the process that both companies were reduced to just a handful of rifleman as darkness fell on the 15th.

The attack continued after dark, and Company L made some progress among the olive orchards and terraces, and even penetrated German lines. There they were met with heavy automatic weapons fire. Without sleep, little food and water, and with heavy casualties, Company L was near the end of its rope.

The 141st, coming at San Pietro from the south, had stopped along with the 143rd to regroup. The battalion mounted an attack from the valley side of the battlefield at about 5:30 pm. Artillery pounding San Pietro helped them get to the verge of the town, but there the stone walls surrounding the village slowed them, as did the booby traps, mines, and barbed wire attached to the walls. German troops in buildings overlooking the barriers were also firing down from the upper floors directly into the American forces.

Once the attack had been slowed to a halt, the German mortars, planted in dozens of locales around Sammucro and across the valley at Monte Lungo, began to zero in the 141st with pinpoint accuracy. The four companies from the 141st’s 2nd Battalion involved in the attack were whittled down to a handful of officers and a few score riflemen by early the next morning, but a smattering of troops managed to break through the boundaries of San Pietro.

The one major success of the day’s attacks was happening simultaneously—over on Monte Lungo, the 142nd was lunging up the hill. One battalion attacked the northwestern side of Lungo, while another attacked the center. The 1st Italian Motorized Brigade was once more involved and took the southern route against the Germans.

The 1st Battalion on the right flank engaged in a number of fierce firefights. It knocked out more than a half dozen machine-gun nests on its way to the top of the mountain.

The 2nd Battalion likewise made a quick journey to the top, during which it was able to induce a newly captured POW into pointing out 15 gun emplacements on the mountain. They were quickly zeroed in and subsequent fire saved American soldiers throughout the valley. Monte Lungo fell by 1:35 amon December 16, which proved vital to the capture of San Pietro as well.

Come daybreak, the Germans tried to reinforce the village, but with the 142nd now on top of Lungo, exposing German posts in the town and valley, and with Sammucro still held by the 1st Battalion of the 143rd, the panzer troops were now in a desperate position.

They acted accordingly. A fierce counterattack ensued on the afternoon of the December 16, focused on the American right flank, where the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 143rd were positioned. Here, Company I—which had been pulled off the top of the mountain and asked to join the assault against San Pietro—got caught in the first blaze of fire from the Germans. They were above the village, just to the northeast, and they got smashed.

The CO and second in command were both killed in the initial attack, forcing Company I to reel back. But the unit held its ground thanks in part to Pfc. Charles Dennis, who rallied the platoon with fierce machine-gun fire.

Company K, too, was quickly drawn into the fight. Led by Captain Henry Bragaw, “a mild-mannered horticulturalist with a strawberry-colored handlebar mustache.” They were able to stop the counterattack, despite having lost communication with the battalion command post.

A withering line of artillery fire was also essential to stopping the Germans. At the height of the fight, shells were landing within 100 yards of the American lines—a dangerous rain of fire, but so accurate that German troops could not penetrate it.

By 1 amon December 17, the fight was essentially over. The Germans began quickly withdrawing from the village, leaving just a smattering of troops to cover the retreat. What was left of Companies I and K proceeded into San Pietro and the area just to its north. In the process they collected 10 German POWs not quick enough to escape the town.

San Pietro had been turned into a rough pile of stones. A few walls with window openings were huddled together, suggesting the buildings from which they were derived and the shape of an ancient Italian village. The essential outline of the town’s church, dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel, remained visible, but from a distance it looked like a sand castle kicked several times over. Within one of the church alcoves, an armless statue of St. Peter looked out mournfully on what was left of the village.

Even as the 36th Division began sweeping through the remains, the German soldiers were racing away to their next line in the mountains, five kilometers away.

Up on the mountain, the weary 1st Battalion of the 143rd was relieved by a battalion from the 141st. Exhausted and unshaven, on wobbly legs and empty bellies, remnants of the outfit made a tired descent from Sammucro after spending the better part of 10 days on its heights. Someone estimated that the 1st Battalion had pitched 2,000 hand grenades among the rocks of Sammucro during its stay up on the heights. That was more than a division would typically use in combat.

Of course, all of those grenades were lugged up to the top of the mountain by hand. Mortars, too, were used at a level three times the usual. They, too, were carried up on the backs of the human mules who had scaled Hill 1205 time and again.

Down below, Riley Tidwell was still waiting for his captain to come down off the mountain. It had been three days now that Henry Waskow lay wrapped in a tarp, still trussed up in the rope that had been used to secure his journey on a litter off the summit. His remains had lain with face covered, boots exposed, on his litter on bare ground, against yet another old stone wall in this land of old stone and mud.

Waskow was far from alone up at the station where the mule train ended. Many more dead were waiting to come down the mountain, and many more of the living congregated around them, resting themselves on the way, sitting among the dead bodies, as if they weren’t dead, but simply dead-tired, like the soldiers of the 143rd seated around them.

That didn’t ease things for Tidwell. It just wasn’t right for the captain to be so long on the mountain. Tidwell decided to take matters into his own hands. He “acquisitioned” a mule from one of the trains and took off by himself up the trail, determined to fetch Captain Waskow. There was still sporadic gunfire on the hillside; still the persistent mortar fire from stubborn German troops slowly retreating on the far side of Sammucro. But the slow process of bringing the dead off the mountain continued.

Riley Tidwell found his captain just where he’d left him. He strapped Waskow over the mule like others were doing with the dead at the head of the trail and headed down. For a time, the sporadic German fire focused on the mules coming down off the mountain. Tidwell was nicked by shrapnel: once across the back, once on the wrist, once by his left ear. The last wound left him bloody but still upright as he neared the base of the hill. It was his feet that were giving him the most pain.

“Here comes Riley,” he heard someone from down below call, “and he’s got Captain Waskow.”

Several people helped him take the captain off the back of the mule and lay him down with the others who’d been brought down the mountain that day. At the field hospital, they sewed 15 stitches into the wound by Riley’s ear and decided that his feet were bad enough to send him to the hospital.

Ernie Pyle was still at the shed below, watching the procession of mules and men, mingling with the living soldiers at the foot of the mountain, as the dead were placed among them.

All day long the bodies were carried down the mountain on the backs of mules, according to Pyle, one at a time, as the exhausted men of 1st Battalion sat around talking “soldier talk.” They would get quiet as each fresh body was laid next to the road that ran by the shed—convenient for taking the corpses away for their final disposition.

Pyle saw the gangly Texas private he had run into in the shed a few days earlier

coming down the hill with a group of four other bodies on four more mules. He watched as they wound their way down the last few yards and got within earshot of the bottom of the hill.

Someone in the group said, “This one is Captain Waskow,” and Pyle instantly noted a change in mood. What had been somber air became all the more heavy. A number of them stood up, tamped out cigarettes, and slowly sidled over to help him off the mule.

There he lay with all the rest, but Pyle could tell this death was a little different. This one was a little harder to take. One by one, the men from the company came over to pay their respects. Pyle carefully noted how they did so, catching the small gestures, the soft words. Later, he asked a few questions about the man who had just come down, listened for a while to the muted expressions of sorrow coming from the men who had known him best—the men who had served with him.

As the night continued in its black vein, Pyle slipped away, back to his bedroll in the cowshed to ponder this war and think on deaths like these. He shut his eyes and tried to get some sleep.

The way that Henry Waskow came off that mountain, the way his fellow soldiers treated him when he came down, inspired Ernie Pyle’s most powerful war column, “The Death of Captain Waskow.”

This article is adapted from Tim Brady’s 2013 book, A Death in San Pietro (excerpt reprinted by permission of Da Capo Press). In addition to detailing the story behind Ernie Pyle’s famed column, “The Death of Captain Waskow,” Brady’s book tells how John Huston’s acclaimed documentary The Battle of San Pietro was filmed during the same action. Both works can be found online. Pyle’s column: http://mediaschool.indiana.edu/erniepyle/1944/01/10/the-death-of-captain-waskow.

Huston’s film: https://archive.org/details/ battle_of_ san_pietro