By Alexander Zakrzewski

On the evening of October 13, 1939, sailors aboard the British battleship HMS Royal Oak had no reason to believe they were in danger of anything other than cold and boredom. Great Britain may have been at war with Germany, but the battleship was moored far from any fighting in Scapa Flow, the base of the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet, and one of the most secure anchorages in the world. No one suspected that lurking just below in the murky water, waiting to strike like a wolf on the hunt, was one of Nazi Germany’s deadliest U-boat aces.

Gunther Prien was born in 1908 in the Baltic city of Lubeck, one of Northern Europe’s oldest and most storied seafaring cities. At the time, the pride of Germany was Kaiser Wilhelm II’s vaunted High Seas Fleet, and like many German boys Prien grew up dreaming of becoming a naval officer. He diligently saved up enough money from odd jobs to afford him to enroll in seamen’s school and begin a career in the merchant marine. He served on a number of merchant ships, eventually accumulating enough experience to obtain his captain’s license.

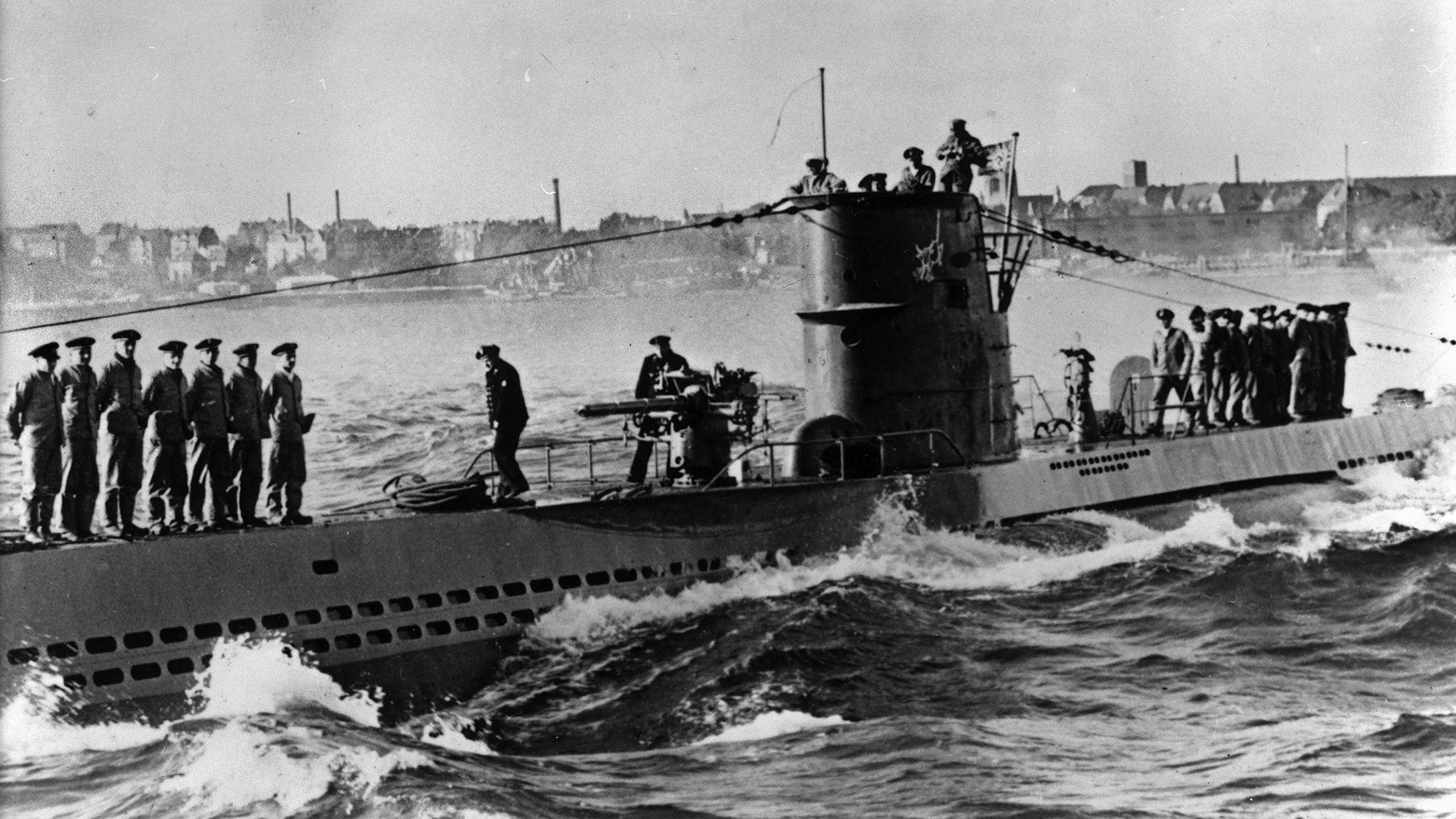

Prien joined the Reich Labor Service in 1932 where he became fully indoctrinated in Nazi ideology. Shortly afterwards, he became a full-fledged party member. Adolf Hitler, who became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, had no intention of adhering to restrictions on naval rearmament embodied in the Treaty of Versailles. He set in motion covert plans for a new modern Kriegsmarine, complete with battleships, aircraft carriers, and submarines. For Prien, this meant opportunities he could only have dreamed of in the former Imperial Navy. After a year serving as an ordinary seaman aboard the light cruiser Konigsberg, Prien landed a coveted spot at the new U-boat training school in Kiel.

U-boat ace Werner Hartmann tapped Prien to serve on his submarine when he was assigned to patrol Spanish waters during the Spanish Civil War. Although the German forces were officially neutral observers, the conflict proved the perfect testing ground for the Wehrmacht’s new weapons and tactics.

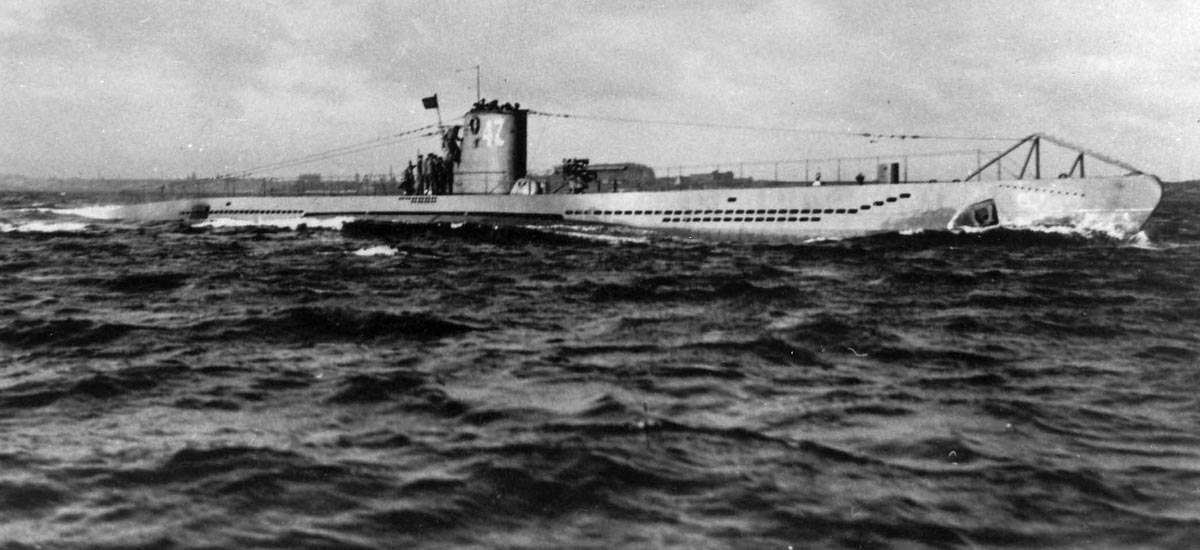

Prien was promoted to lieutenant in 1938 and given command of his own boat, U-47. The newly minted U-boat commander was on patrol with U-47 west of the Bay of Biscay when war broke out. In the first week of September 1939, he sank three British merchant ships, a feat that earned him the Iron Cross Second Class and two weeks leave for his crew. It also earned him a private meeting with Karl Donitz, the supreme commander of the U-boat arm.

Donitz had a unique vision for the role the Kriegsmarine would play in the coming conflict. He fervently believed that only by waging a so-called tonnage war on a much greater scale than the one waged by U-boats during the previous conflict could the Kriegsmarine starve the British Isles into submission. Yet Hitler had shown only a passing interest in the U-boat arm of the Kriegsmarine. What the submariners needed was a spectacular victory to prove their worth and galvanize the attention of both the Fuhrer and German public.

“Do you think that a determined commander could get his U-boat inside Scapa Flow and attack the enemy naval forces lying there?” Donitz asked Prien in the meeting. As the British Royal Navy’s base, Scapa Flow was deemed impregnable, but Donitz explained that he had evidence of a possible way in. He gave Prien the information and told him to report back in three days with his assessment. He assured him that no matter what he decided, his reputation would not suffer in the eyes of the high command. Prien reported the next day that it was possible, and that he was the man to do it.

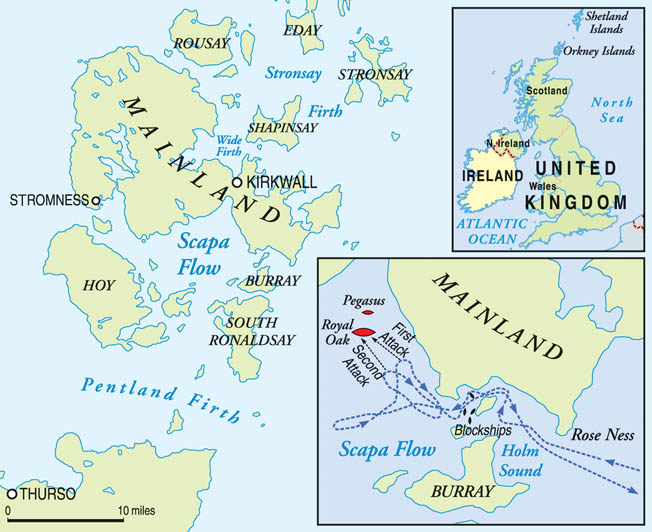

The Scapa Flow archipelago lies between the Scottish mainland and the Orkney Islands. The natural harbour has served as a safe anchorage for fleets since the days of the Vikings. Scapa Flow’s defenses included searchlights, gun batteries, mines, submarine nets, patrol boats, and block ships. The naval base had some glaring weaknesses, though.

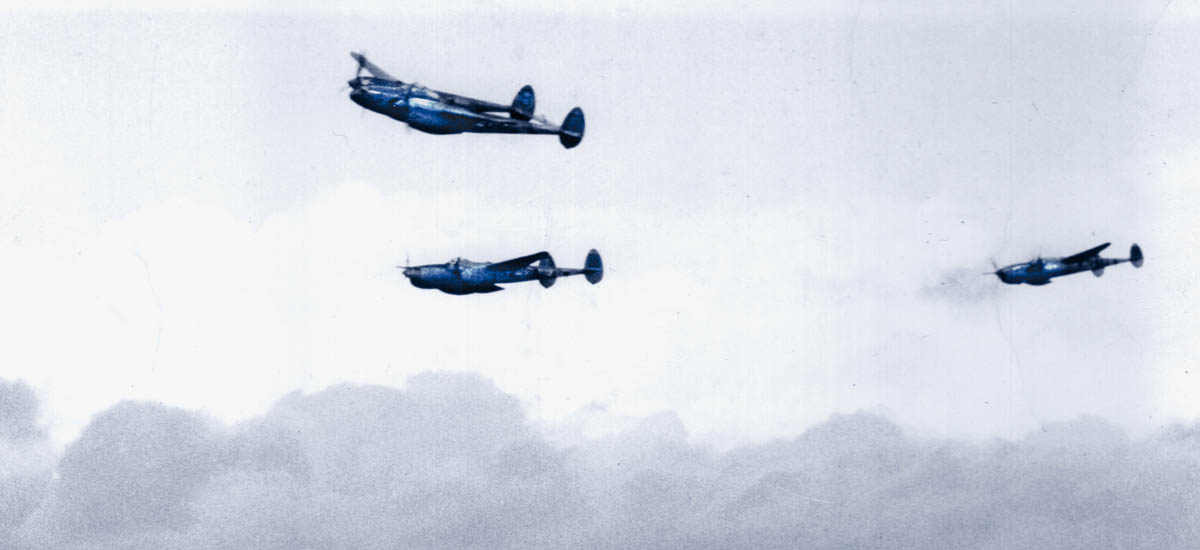

Shortly before war broke out, Donitz had received a report from a passing German merchantman that in Kirk Sound, the northernmost of the harbour entrances, there was a noticeable gap between the block ships. Luftwaffe reconnaissance planes later confirmed that there was, indeed, a 17-meter hole through which a U-boat could conceivably pass. Better yet, there were no lookouts or searchlights, either. It was a galling oversight on the part of the British Admiralty and the perfect place for an intrepid intruder to strike.

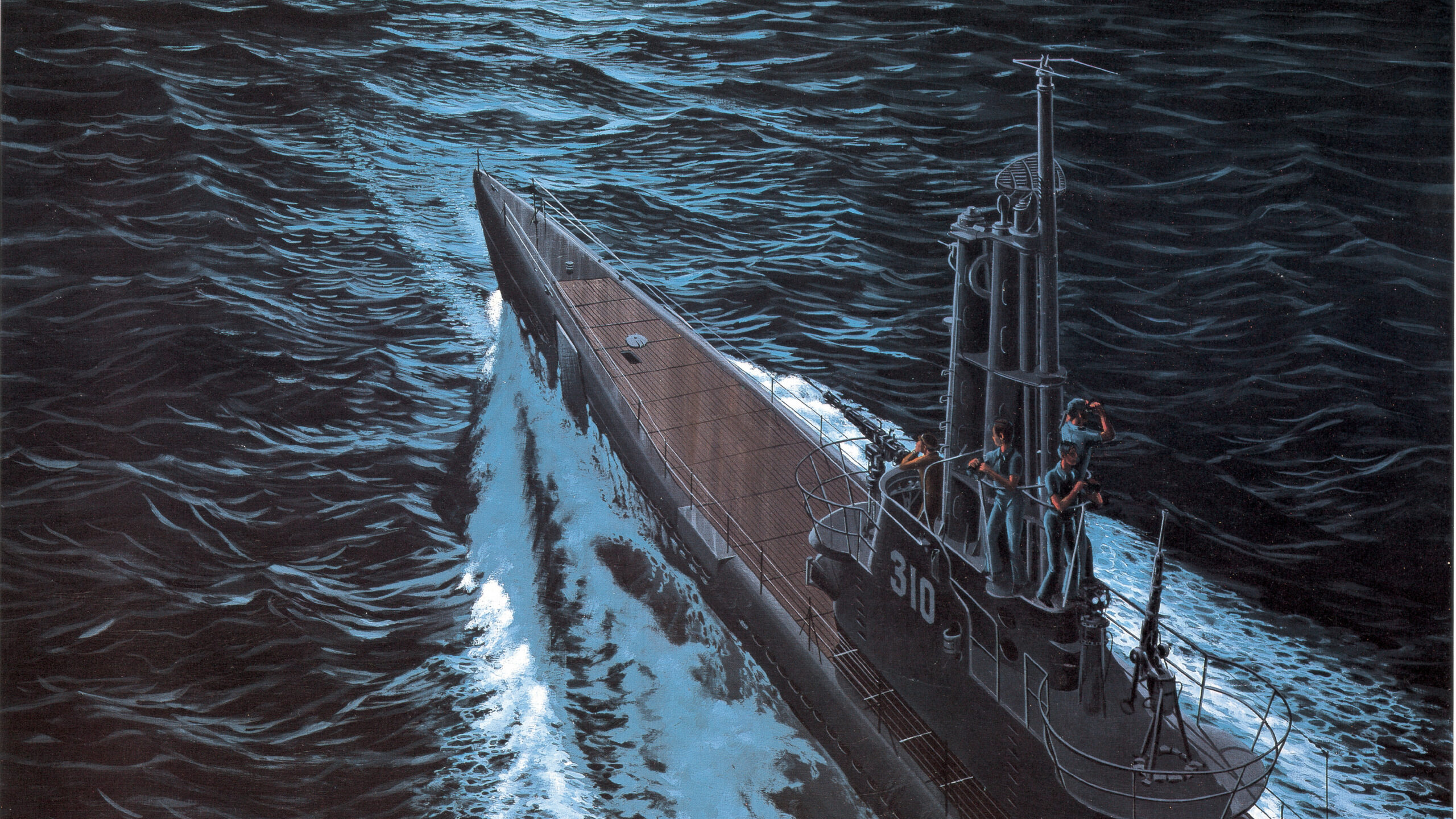

On the evening of October 14, 1939, Prien stood on the conning tower of U-47, anxiously scanning the entrance of Kirk Sound for any sign of enemy patrols. When he was satisfied that there were none, he gave the order to begin navigating the choppy waters. Finding the gap between the block ships would have been a tricky undertaking in broad daylight. On a moonless night with only the aurora borealis offering some illumination, it was like threading a needle. At one point, the U-boat became snagged on an anchor cable and forced to abruptly reverse engines at full power. Moments later, Prien’s heart almost stopped when the boat was suddenly caught in the headlights of a passing car. Incredibly, the driver took no notice. “We are inside!” he whispered down the conning tower.

When U-47 finally entered the harbour, Prien began scanning it for his prey. It proved surprisingly difficult. A week earlier, a large British task force of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers had left Scapa Flow for a mission in the North Sea and still had not returned. Although this meant fewer sentries for U-47to worry about, it also made it harder to find a suitable target. Prien knew he had to find one fast. Every second he spent in the anchorage increased the risk of detection significantly. At the same time, he hated the thought of having gone through so much effort only to sink a tanker or cargo ship. At last, he spotted in the distance the massive silhouette of what could only be a British battleship. It was the HMS Royal Oak.

Prien’s heart skipped a beat. He knew this was his chance. He called down the conning tower for four torpedoes to be readied and fired. With each firing, he could feel the boat pitch slightly, a signal to begin counting down the three-and-a-half minutes it would take for the torpedoes to cross the roughly four thousand yards to the target. But after what seemed like an eternity, all he heard was a small, muted blast near the Royal Oak’s bow. One torpedo had misfired, and of the other three, only one had actually made it to the target, where it struck the ship’s anchor chain and exploded harmlessly.

Surprisingly, no searchlights shone, no alarms sounded, and no destroyers sprang into action. It was later revealed that the duty watch on the Royal Oak dismissed the disturbance as a snapped anchor cable or minor internal disruption. Prien turned around and fired two more torpedoes from his stern tubes. But again, nothing happened.

Cursing his luck, Prien put some distance between himself and the Royal Oak to cool off and reload his torpedoes. It was now past midnight. The next shots had to count if he were to have enough time to escape before daylight. Shortly after 1:00 a.m. he fired a spread of three more torpedoes. This time, all three hit their target, cutting massive holes just below the waterline on the ship’s starboard side. Almost immediately the ship began to heel as tons of seawater poured in. Before anyone on board could make sense of what was happening, the cordite magazines ignited, and massive towers of flame shot towards the sky, sending pieces of the ship flying in all directions.

Within minutes, the Royal Oak began to roll over. All along the deck, sailors plunged into the frigid water, desperate to escape the flames. Those still on the lowest decks stood no chance. Approximately 800 British sailors went down with the ship. Prien knew the ship had been destroyed when the 15-inch guns broke off and crashed into the sea. “He’s finished!” he informed his crew.

U-47 made a beeline for Kirk Sound. But even when travelling surfaced and at full speed, the submarine could only make 17 knots, making it easy prey for the speedy British destroyers that were already hurling their depth charges at anything that moved.

Fortune initially seemed to be with the crew of U-47, but it turned out the crew was not completely out of danger. While still off the coast of Scotland, two British destroyers caught up with them, forcing them to crash dive. Prien tried to outmaneuver his pursuers underwater, but the destroyers were armed with ASDIC sonar systems and followed his every move. For hours, the crew of U-47 sat helplessly on the seafloor while depth charges exploded all around and the ghostly ping of the ASDIC rang incessantly in their ears. The pinging eventually stopped, and the sound of propellers grew fainter and fainter until it disappeared altogether. Prien surfaced to find no sign of his pursuers. It was smooth sailing from then on.

When U-47 docked in Wilhelmshaven, both Donitz and his superior, Grossadmiral Erich Raeder, came on board to congratulate and decorate the crew. Hitler was also thrilled. He was so delighted that he sent his private plane to pick up Prien and his men and fly them back to Berlin for a parade and ceremony at the Reich Chancellery. There he personally decorated Prien with the Knight’s Cross and even hosted the entire crew for lunch. That night, they were Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels’ personal guests at the Wintergarten Theater.

Prien became a national hero overnight. The sinking of the Royal Oak was precisely the inspiring story the country needed to hear at a time when most Germans were still wary of another war with Britain and France. For the Kriegsmarine, particularly the U-boats, it was a propaganda triumph that could not have been scripted any better.

The press quickly nicknamed Prien the “Bull of Scapa Flow,” and from then on, everywhere he went he was greeted by cheering crowds and news cameras. A ghostwritten memoir of his exploit, titled My Way to Scapa Flow, quickly became a national bestseller.

Prien returned to duty in November 1939. Over the next year and a half, he was a scourge on British shipping. In June 1940 alone, he accounted for 10 percent of the total tonnage sunk by both the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe. That October, he led a wolf pack of U-boats in a ferocious attack on a British convoy that destroyed eight enemy ships. When he returned to port, he became just the fifth German officer to have Oak Leaves added to his Knight’s Cross.

The Royal Navy gained the edge in the Battle of the Atlantic in 1941 with the advent of key advances in anti-submarine weaponry and tactics, coupled with naval reinforcements from Canada and the United States. On February 20, 1941, U-47 departed Lorient, France, on her 10th patrol. Two weeks later, she went missing somewhere south of Iceland.

To this day, it has not been confirmed what exactly happened to U-47. Two British destroyers, HMS Wolverineand HMS Verity, were credited with having blown apart U-47 with a skilfully laid pattern of depth charges. Yet there is some speculation that the U-boat might have been destroyed by one of its own circling torpedoes. The loss was kept hidden from the German public for almost three months. Fuhrer Headquarters announced Prien’s loss, as well as his posthumous promotion to commander, in late May 1941.