By Robert L. Durham

Lieutenant Frank Boccia could hear the platoon ahead moving forward, reconnoitering by fire, spraying the trail and the jungle alongside it with M16 and M60 fire. Then the screaming started. Yells for a medic and screams of agony rent the air. He could hear a massive volume of enemy small arms fire and rocket-propelled grenade explosions. This went on for several minutes as the first body was brought back on a poncho stretcher.

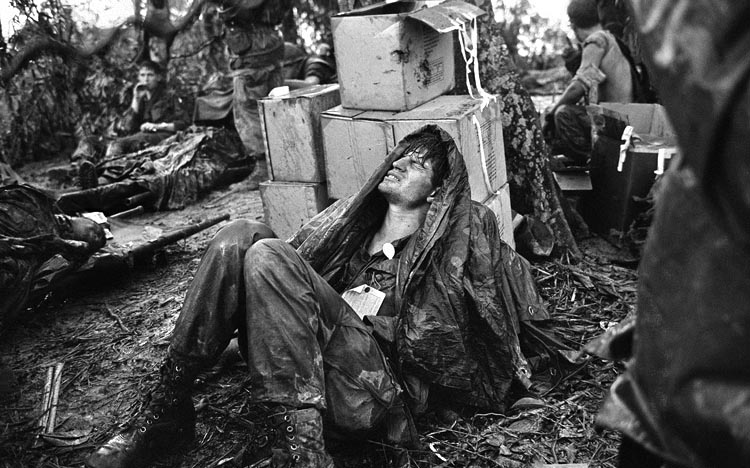

Soon more American troops came down the hill returning, from the front line. Some of the wounded staggered back on their own, some were supported by fellow soldiers, and some were carried back on poncho stretchers. The wounded were casualties from the first assault by the soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division on Ap Bia Mountain in the remote and rugged A Shau Valley.

The A Shau Valley is situated next to the Laotian border less than 100 miles from the demilitarized zone that separated North Vietnam and South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. In March 1966 North Vietnamese forces had overrun the U.S. Special Forces camp at the south end of the valley in a savage 38-hour battle in which the wounded were whisked away in evacuation helicopters and the remaining survivors conducted a two-day fighting retreat through the jungle before they, too, were airlifted to safety.

Afterward, North Vietnamese Army (NVA) used the valley as a jump-off point to attack the imperial city of Hue during the bloody countrywide Tet Offensive in January 1968. Several major operations by the U.S. Army and Marine Corps, such as Delaware, Somerset Plain, and Dewey Canyon, conducted after the Tet Offensive sought to keep the North Vietnamese in the A Shau Valley off balance and on the defensive.

The search and destroy sweeps conducted during these large-scale operations uncovered weapons caches, sophisticated communications equipment, and supply trucks. But the NVA units in the valley avoided set-piece battles with the Americans during these operations, preferring instead to fight on their own terms. Therefore, the results of the three operations were limited.

Ap Bia Mountain stands alone in the A Shau Valley. It is not connected to nearby mountain ridges. The Americans called it Hill 937, naming it by its height in meters. The local Montagnard tribesmen had a more colorful name for it: the Mountain of the Crouching Beast.

U.S. Army General Creighton Abrams ordered an operation in June 1968 to clear out the A Shau. Abrams replaced General William Westmoreland as head of the U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam, the commander of U.S. forces in South Vietnam, when Westmoreland was appointed chief of staff of the Army in July 1968.

Abrams assigned the task to the crack troops of the 101st Airborne. The 1/502nd of the 101st Airborne dropped into landing zones in the southern A Shau on March 1, 1969, in Operation Massachusetts Striker, and fought several firefights, culminating in a three-day battle at Bloody Ridge. They suffered 35 killed and 100 wounded. The operation concluded on May 8.

As a result of this operation, the Americans planned a much larger operation named Apache Snow. It was scheduled to begin on May 10 with a helicopter assault by companies from 1st Battalion, 506th (1/506th) Airborne and the 3rd Battalion, 187th (3/187th) Airborne, all part of the 101st Airborne Division. The187th’s nickname was the Rakkasans.

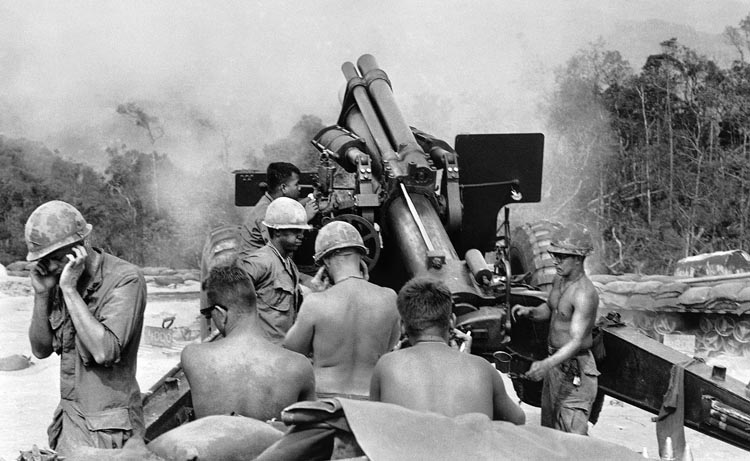

Before the American paratroopers were inserted on the first day of the operation, U.S. long-range artillery deployed at nearby firebases blasted the jungle to create 30 landing zones. The large number of prospective landing zones was meant to confuse the North Vietnamese so they would not know for sure where the men of the 101st Airborne would land. The division intended to use just five of the 30 landing zones.

Companies A, C, and D, 3/187th, landed unopposed at landing zones two near the Laotian border, using 65 UH-1 helicopters for transport. The helicopter flight looked “like a swarm of giant green dragonflies,” recalled Boccia. Landing zone 2 was 1,800 meters northwest of Hill 937. At 8 amDelta Company was the first down. The Rakkasans encountered only light resistance as they discovered a network of enemy bunkers within a few hundred yards of their landing zone.

The commander of the 3/187th was Lt. Col. Weldon “Tiger” Honeycutt. A hard-bitten officer, he was a veteran of the Korean War where he served under Westmoreland. Honeycutt’s troops in Vietnam knew him as “Blackjack” from his radio call sign.

At 9:30 amHoneycutt, his staff, and an 81mm mortar platoon landed and relieved Charlie Company of its duties on the landing zone, ordering them on a reconnaissance in force toward the Laotian border. Honeycutt received intelligence that the NVA had a logistics center on the top of Hill 937, so he ordered Delta Company to check this out and set up a perimeter for the battalion command post. He did not expect excessive enemy resistance because the NVA often retreated across the Laotian border, which was only 1,600 meters away, when confronted by American troops. Although the resistance was light, Honeycutt felt that, given the number of enemy bunkers found, there might be many enemy troops in the vicinity. Therefore, he ordered Bravo Company to be released from its reserve position on Firebase Blaze to join in the attack.

Honeycutt ordered Captain Charles Littnan, commanding officer of Bravo Company, to move out and get as close to Hill 937’s peak as he could before nightfall. He planned to use the mountain as the battalion command post. Littnan ordered his platoons to move out. The first to step off was Lieutenant Marshall Eward’s 2nd Platoon. It was followed by Boccia’s 1st Platoon, which was followed by the company command post. The 3rd Platoon followed the command post, and Lieutenant Charles Denholm’s 4th Platoon brought up the rear. They advanced through jungle terrain consisting of tall canopy, bamboo, and thick vines. Near dusk, the head of Bravo was hit by fire from RPGs, AK-47s, and machine guns. They called down air strikes and pulled back to a night defensive position.

On the morning of May 11 Bravo Company moved forward again, this time with Boccia’s 1st Platoon in the lead. They came to an area of the trail where the bamboo had been knocked down in such a way that the men had to crawl. They found four dead NVA soldiers, one of whom had documents in his possession, which were sent to the S2 battalion intelligence in the rear. The prisoner interrogation revealed that the American troops were facing the 29th NVA Regiment, an elite unit known as the Pride of Ho Chi Minh.

The dense bamboo underbrush gave way to towering teak trees and the visibility increased, in some places, to 100 meters. The path they were following along the ridge widened and they found several blood trails. Littnan ordered Boccia to continue moving forward. When Boccia’s radio-telephone operator heard this, he jumped up to slip on his radio. When he did, one of the straps broke. Littnan, impatient for the strap repair, ordered Denholm to take over the lead.

Denholm had Specialist Fourth Class Aaron Rosenstreich take the point, with SP4 John McCarrell in the slack position. They did not go far before Rosenstreich found a communications wire. It looked like it ran from Laos to the top of Hill 937. Denholm radioed Littnan, who came forward to look for himself. Littnan had Denholm send a squad down the draw to see where it led. They followed it a short way, then came back to the platoon.

When the platoon started back up the trail, a sniper fired on them. Rosenstreich fired into the treetops and then started to conduct a reconnaissance by fire. He shot at anything that looked like a likely sniper location as he slowly moved forward. An NVA soldier popped out of a spider hole in the center of the trail and shot Rosenstreich in the chest. Another NVA fired an RPG from a bunker and hit McCarrell in the chest. A claymore mine that McCarrell was carrying over his shoulder exploded, blowing him to pieces and peppering Lieutenant Denholm with shrapnel. Machine-gun fire and RPGs were hitting everywhere.

Denholm crawled forward to Rosenstreich, who was lying off the trail, leaning against a tree. Denholm yelled down the trail for his machine gunner to bring up the M60. SP4 Terry Larson ran up the trail ahead of the machine gunner, and then pitched forward, shot in the head. SP4 Donald Mills, the machine gunner, ran up the trail right after Larson. The same enemy soldier who had shot Rosenstreich rose up out of his spider hole and shot Mills in the chest. Mills went down but then jumped up again and picked up his M60. He found that the machine gun had been broken by a bullet, so he picked up Larson’s M16, ran forward, and emptied the magazine into the spider hole.

Denholm started throwing grenades out ahead, but he could not tell if they were doing any good. Unexpectedly, an enemy soldier popped out of a spider hole near him, fired off a few rounds with his AK-47, then ducked into the hole again. Realizing he had left his rifle behind somewhere; Denholm pulled his bowie knife. When the enemy soldier came out of his hole again, Denholm stabbed him in the throat. In shock and bleeding profusely from his shrapnel wounds, Denholm staggered back down the trail.

Sergeant Louis Garza took charge of the platoon and started sending men up the trail to bring back the three killed and seven men who had been wounded. With Denholm’s platoon cleared from the trail, Littnan sent a forward observer up the trail to coordinate an artillery strike on the enemy position. The forward observer called in two Bell AH-1 Cobra gunships to hit the position with aerial rocket artillery.

It was obvious by that time that the Americans had located the enemy forces and they intended to fight. This suited Honeycutt; he ordered Charlie Company to end its reconnaissance in force up the Trung Pham River and attack up Hill 937, keeping parallel with Bravo Company. Delta would work its way up the northern end of the hill. Then, a tragic friendly fire incident occurred. Instead of firing on the NVA, the helicopter gunships bore down on the battalion command post. “Get down! Incoming!” Honeycutt screamed to the 50 men around the command post when he realized what was happening.

The rockets from the first Cobra hit the treetops and rained down shrapnel over a 30-meter area. Some men fell and others ran for cover toward the edge of the perimeter. Honeycutt himself was hit in the back by shrapnel. Blackjack at last got the gunships on the radio and ordered them to stop the attack or he would have the Cobras shot down. The command post had ceased to function. Two men were dead, and 35 others were wounded. To make matters worse, NVA 120mm heavy mortars picked that time to shell them from across the border. Some of the wounded were hit again as a half dozen big shells slammed into the command post.

With his command post shot up, Honeycutt knew he could not properly support Bravo Company, so he ordered Littnan to pull back 100 meters and form a night defensive perimeter. He called Captain Dean Johnson, commanding officer of Charlie Company, and told him to start his company on a reconnaissance in force straight toward Hill 937. Honeycutt ordered Captain Gerald Harkins, commanding Alpha Company, to march his company to the battalion command post and relieve Delta Company. Delta would start a reconnaissance in force the next morning, up the north side of the mountain. Honeycutt had to get the battalion command post straightened out. After taking care of the casualties, he started to bring in replacements from rear-area detachments and staff. Although this did not make up for his losses, it at least got the manpower up again.

At 7 am on May 12 two A-1 Skyraiders strafed and bombed the NVA positions above Bravo Company. After their 20-minute attack, two more Skyraiders began a fresh attack on the enemy positions. When they were done, Captain Littnan ordered Boccia to take his 1st Platoon up the trail. He was told to fall back if he started receiving heavy fire. It took Boccia’s platoon 35 minutes to reach the clearing where Denholm’s 4th Platoon had been hit. Littnan had the mortar platoon prepare the position as they approached. There was no way to bypass the clearing and the NVA had turned it into a killing zone, with bunkers lined up the mountain with clear fields of fire.

As Boccia’s men advanced on the clearing, the men flattened themselves on the ground. The point man saw two NVA, but he had not been spotted yet. Then, the enemy saw him and set off a few claymore mines. As the shrapnel flew, the NVA also opened fire with their AK-47s and a machine gun. The Rakkasans responded with their M16s. Boccia spotted numerous enemy bunkers on the hillside behind the clearing and radioed this information back to Littnan.

The point man spotted a dead NVA soldier in the middle of the trail ahead and a bunker in front of the corpse. Boccia brought up Private First Class James Clifton and SP4 Philip Nelson with a recoilless rifle. They fired a couple of rounds at one of the bunkers, one of which went into the aperture of the bunker, collapsing it. The NVA countered with RPG fire. One of the RPGs hit right in front of them. The recoilless rifle flew into the air, and Clifton and Nelson both went rolling down the bank; surprisingly, neither was hurt.

This seemed to be the signal for the NVA to engage the 1st Platoon. RPG rounds slammed into the trees over their heads, raining shrapnel on them. The fire was so intense that for a time they could not even return fire; instead, they hugged the ground. Seven men were wounded, one of whom was the medic. Boccia got his wounded out and returned to the location of their perimeter from the previous night. He put his wounded onto stretchers and sent them back to the battalion command post. Fighter bombers arrived a few minutes later and started hitting the clearing with 1,000-pound bombs and napalm. When the jets had finished, the five fire support bases supporting the airborne troops sent howitzer rounds crashing into the enemy positions.

Honeycutt ordered his engineers to open a landing zone for Bravo Company. Nearly 700 meters separated them from the battalion command post, and they needed a place closer to their own command post where they could evacuate any future wounded. A Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopter, known as a “Huey,” arrived over the Bravo Company command post and hovered overhead while the engineers started rappelling down. The first one made it to the ground, but then the NVA began firing on the Huey with their machine guns. When the helicopter was struck by enemy fire, the men on board cut the rope so they could get out. An engineer hanging on the rope fell to the ground, breaking both of his legs.

Honeycutt called in fighter bombers and they pounded the enemy position with 30 bombs. Another Huey came in to land the rest of the engineers. This time, it was not hit by machinegun fire but by an RPG round. The chopper made an emergency landing on its side. Men from Bravo Company rushed to aid the men on board the helicopter, pulling out 10 wounded before the Huey blew up. Honeycutt gave up on the Hueys and ordered the engineers to hump to Bravo.

Boccia’s platoon was again designated to take the lead for Bravo Company on May 13. Before they initiated action, F-4 Phantom jets struck the enemy bunkers with 1,000-pound bombs. Boccia radioed to Littnan that the bombs were landing too close, shrapnel was falling all around his platoon. SP4 Nelson was hit in the side by shrapnel. Littnan radioed his forward air controller, who assured him the bombs were hitting on target. On the next run, SP4 Myles Westman, who did not have his helmet on, was killed by shrapnel that struck him in the back of his head. Due to the casualties it suffered, Boccia’s platoon was taken off point.

Eward’s platoon was assigned point instead. Snipers in the trees fired on the platoon before it reached the clearing. They sprayed the tops of the trees on both sides of the trail as they slowly advanced, and snipers fell from the trees as they were hit. Some of the snipers had tied themselves into the trees with ropes around their waists. The dead enemy snipers dangled grotesquely from their perches.

When the Rakkasans reached the clearing, the NVA started throwing grenades. Within a few minutes, five men were wounded. Eward moved two squads forward, spread out in a skirmish line. The line was quickly pinned down by an NVA machine gun in a bunker. Eward ordered his men to bring forward a recoilless rifle. They fired at point-blank range into the bunker, killing the two enemy soldiers inside. Eward’s men advanced a little farther and all hell broke loose. As many as 30 enemy soldiers popped up and began firing RPGs, machine guns, and AK-47s. Three more men were wounded, and the rest retreated down the hillside, dragging the wounded behind them.

Meanwhile, Charlie Company was having troubles of its own. While the main body of the company moved up the ridge, Lieutenant Joel Trautman and the 1st Platoon were ordered to stay behind and build a small landing zone so wounded could be evacuated and supplies brought in. They were then ordered to send a squad to Bravo Company with ammunition. The NVA, seeing the weakness of the platoon, brought up reinforcements to strike 1st Platoon’s perimeter. The NVA attempted to overrun the platoon, striking the right flank. When the North Vietnamese got into position, they rose up and attacked with everything they had, killing two men and wounding five. The NVA advanced slowly toward the Rakkasans’ position, firing as they moved. The unwounded men in the 1st Platoon perimeter returned fire and the NVA skirmish line retired, but not before wounding another American.

The leading platoons, running a gauntlet of sniper fire, bogged down completely after suffering five wounded. They established a night perimeter strung out on both sides of the ridge, 150 meters below the top of Hill 937. An enemy mortar battery in Laos shelled them with its 120mm Russian mortars. The NVA had their location zeroed in and walked the rounds across the night perimeters, wounding five men and destroying the equipment of an Army camera crew.

Delta Company was trying to get into position for its attack when it was hit by RPGs, and eight men were wounded. They called in a medevac helicopter, but it could not land, so a basket was lowered. The first man was loaded, and the helicopter started to winch him up, when the ship was hit by an RPG. It fell straight down, crushing the wounded man. The spinning blades hit another wounded soldier and a radioman who had been guiding the ship in. The men on the ground rushed to extract the four-man crew but only rescued the badly injured pilot before the helicopter exploded.

The Rakkasans had assaulted the hill for three straight days and nights with infantry, bombs, artillery, and napalm. The NVA was still dug in on the mountain and did not show any signs of leaving. Instead, it looked like they were receiving reinforcements from Laos. Lt. Col. John Bowers, the commanding officer of the 1/506th “Currahees,” received orders from brigade headquarters to move north to Hill 937 to add weight to the attack. The 1/506th had two smaller hills, Hill 800 and Hill 900, which it needed to secure before it arrived on Hill 937. That objective would require several days.

On the morning of May 14, Honeycutt tried to get a coordinated attack moving. He ordered Bravo Company and Charlie Company to hit the west side of the mountain. He also ordered Delta Company, as soon as it had evacuated its wounded and dead, to attack Hill 937 from the north. U.S. howitzers had been firing all night long, and the artillery from all five supporting fire bases increased firing. When the artillery completed its fire mission, planes started coming in, dropping bombs and napalm.

At 8 amBravo and Charlie moved out simultaneously from their night perimeters. In Bravo Company, Eward’s 2nd Platoon led, followed by Boccia’s 1st Platoon. For Charlie Company, Lieutenant James Goff’s 3rd Platoon led off, and Lieutenant Donald Sullivan’s 2nd Platoon followed it. Trautman’s platoon remained to guard the landing zone.

Eward’s Bravo Company platoon moved up with three squads split, one moving up the center of the trail with two M60s and the other two on the ridge to each side of the trail. Their intent was for the middle squad to lay down covering fire while the two flanking squads moved up to try to rush the NVA bunkers from both sides. Unfortunately, things went awry. Four Americans were seriously wounded. The flanking squads pulled their wounded out and moved back. Eward regrouped the two squads and sent them forward again, only to have the NVA explode more claymores. Three men were killed, and Captain Littnan radioed back to Honeycutt that they could not advance.

In Charlie Company, Lieutenant Goff started off with two squads on point. They began receiving fire from three bunkers and, while most of the men poured rifle fire into them, recoilless rifle teams took all three out with flechette rounds. These special-purpose rounds contained winged two-inch steel darts. Goff moved his men into the saddle between Hill 937 and Hill 900, and then moved up the west face of 900 in a skirmish line. The enemy opened fire on them with claymore mines, AK-47s, and RPGs. Six men were wounded before they reached the bunker line on Hill 900. The Rakkasans again brought up 90mm recoilless rifles and opened fire on the bunkers with both high-explosive and flechette rounds.

After 30 minutes, the line of enemy bunkers had been destroyed; however, as soon as the Americans tried to move forward again, they began taking fire from snipers. An F-4 Phantom jet dropped napalm on top of Hill 900, halting much of the resistance.

Captain Johnson radioed Honeycutt that Charlie Company was 40 meters from the top of Hill 900. A few minutes later, the NVA counterattacked by charging down from the top of Hill 900 and others attacked from Hill 937 and hit Goff’s 3rd Platoon’s left flank. The enemy soldiers who were hidden in the draw started firing on them from the rear. They had two dead and 15 wounded and requested permission to withdraw. Honeycutt ordered Johnson not to pull his men back because that would open Bravo Company’s right flank to attack. Johnson ordered Sullivan to move his platoon up on Goff’s left flank.

In Bravo Company’s sector, Littnan ordered the 4th Platoon, which was under the command of Sergeant Garza following Denholm’s wounding, to move into position for the attack. Fighter bombers softened the site once more with 1,000-pound bomb airstrikes and an artillery preparation. Garza led three separate assaults on the clearing with no success. He then tried attacking up the left side of the ridge with a half dozen men. Garza took point for the assault. Snipers in the trees began firing at him. To locate the snipers, he ordered his troops to fire into the treetops. Three dead enemy snipers fell out of the trees. The American soldiers slapped fresh magazines into their rifles and continued firing into the trees as they moved forward. They managed to kill another sniper.

Garza realized that nearly all of the fire his men had been receiving came from the treetops. He had his entire platoon line up in a skirmish line and move forward shooting into the trees. More snipers fell dead out of the trees. As he surveyed the situation, Garza realized that the bombs and artillery had been more effective than he knew. Most of the bunkers in the first line had been blown up with a large enemy body count. As Garza’s 4th Platoon began to establish a position, they began taking fire from the second line of bunkers and had to withdraw.

Meanwhile, Charlie Company was being badly battered, the NVA hitting both lead platoons. Over half the men in Sullivan’s platoon were killed or wounded. Charlie Company had ceased to exist as an effective fighting unit and was pinned to the side of Hill 900. The two platoons had two killed and 35 wounded so far, and the NVA was still assaulting. There was no place that was safe. A group of stretcher bearers was ambushed, adding seven more wounded. When a relief party went out from the company command post to aid them, they were also ambushed.

When Captain Johnson asked Colonel Honeycutt if he could withdraw, Honeycutt had no choice but to grant permission this time. With Charlie withdrawing, Honeycutt had to order Bravo to withdraw. They had taken 30 casualties and lost all gains they had made. When they saw Charlie Company retreating, the NVA attacked. Firing and throwing grenades, they advanced against the front and both flanks of the company. One of them fired an RPG into a team of stretcher bearers, killing the wounded man and three other men. Johnson radioed Lieutenant Trautman to bring his platoon up from the landing zone to help. Trautman was short a squad that he had sent to Bravo Company earlier, but he took his remaining men up the hill.

What Trautman found stunned him. Captain Johnson was in shock and could not even answer Trautman when he asked the status. Trautman brought his platoon up behind the other platoons; shortly afterward, Boccia arrived with his Bravo Company platoon to reinforce Charlie. When he reached Charlie Company’s landing zone, he was surprised to learn there was no security at all. Trautman had been ordered to leave the position. Boccia found a row of casualties and had his medic do what he could for the wounded. When he located Johnson, he was sitting on the ground, staring off into space. Johnson told Boccia he lost his company and did not even know what he did wrong. In two hours of fighting, Charlie Company had lost its commanding officer, two platoon leaders, its first sergeant, two platoon sergeants, six squad leaders, and 40 enlisted men.

The dead and wounded were airlifted to the battalion landing zone in a painstaking manner by Chief Warrant Officer 2 Eric Rairdon, who evacuated the wounded in his small OH-6 Cayuse observation helicopter. Rairdon was a legend to the troops for his willingness to pick up wounded in dangerous landing zones under heavy enemy fire. Every time he came to pick up a load, the enemy would try to down his helicopter with machine-gun or handheld rocket fire.

When the last of the casualties were finally removed, the Rakkasans piled up all the equipment they could not carry and set it on fire. Loading up with everything else, they started to hump their way to Bravo Company’s night perimeters. Their bad luck was not to end quite yet for a pair of U.S. Cobra gunships carelessly raked the rear of the column. The friendly fire incident left four men seriously wounded.

On May 15 Honeycutt realized he would have to attack with only Alpha and Bravo Companies. Before he could consider an attack, though, he had to assure their rear was safe. There were NVA in the draw behind them, preparing to attack the two companies; Honeycutt called in two fighter bombers, which made three runs. On the first run they strafed with their 20mm cannons, on the second run they dropped napalm and 500-pound bombs, and on the last run they used their 20mm cannons again. The U.S. firebases then shelled the enemy with their 155mm, 105mm, and 8-inch howitzers. Then a pair of Cobra gunships made runs firing aerial rocket artillery. The enemy company was shattered. As a result, the rear of the two companies was secured.

When the artillery was finished with the NVA in the draw, they hit the mountain again. Alpha and Bravo Companies then moved out from their assault positions, Bravo’s 4th Platoon had to retake the position they had abandoned the day before. The NVA had set up new claymores, reoccupied many of the abandoned bunkers, and dug new spider holes. Garza had two squads move forward on opposite sides of the ridge. They had not gone far before the NVA set off some of the claymore mines, wounding both point men. Garza radioed Littnan and asked him to send something in to take out the claymores. Littnan ordered him to mark the spot and he would have fighter bombers strike. Garza, with his radioman and three riflemen, crawled up the ridge and Garza threw smoke grenades to mark the spot. The fighter bombers dropped a dozen 250-pound bombs and then strafed the area.

When the planes were done, Bravo struck out again, reconnoitering by fire and spraying the treetops for snipers. They lost more Rakkasans wounded and Garza radioed Littnan for reinforcements. A squad from 1st Platoon was sent forward, and Bravo continued its advance. The top of the mountain had been denuded of trees and resembled a moonscape, with countless craters. When the men passed the tree line, they began receiving heavy fire and were driven to cover. Garza stood up and started throwing hand grenades. “Come on everybody, get up!” he screamed. In response to Garza’s exhortations, the men started crawling up the mountain.

The Rakkasans fought their way past the first bunker line but were stopped cold by the second. They were within 150 meters of the summit. They pulled back a few meters to allow room for a gunship to hit the bunkers. They popped green smoke to show the location and ordered two Cobra gunships overhead to strike 100 meters southwest of the smoke. Incredibly, the first gunship fired an entire salvo into the platoon command post. Two men were killed and 15 wounded, including Captain Littnan. He turned the platoon over to Lieutenant Boccia with orders to continue the assault.

The enemy picked this moment to launch a counterattack. They charged down from the top of the mountain, firing RPGs and AK-47s. The NVA worked their way around Bravo’s right flank and attacked it. Enemy squads hit Bravo’s right flank and its rear in an effort to overrun the company’s landing zone where the wounded were situated. The American troops on the perimeter drove the enemy back with M60 fire. Boccia could not continue the attack. The 4th Platoon was falling back, and he was concerned they might be overrun.

Captain Butch Chappel arrived by helicopter to replace Littnan. Chappel ordered Bravo Company to make another assault. The men, who were fought out, refused. After five days, the attacks on Hill 937 were becoming repetitious. Fighter bombers, helicopter gunships, and howitzers shelled the mountain, but they had little effect on the enemy’s sturdy bunkers. When the American platoons attacked, sometimes they made discernible progress, and other times they made hardly any progress at all. Each time the enemy counterattacked with everything they had. The Rakkasans’ casualties were piling up.

Alpha Company advanced at the same time as Bravo, moving up the path that Charlie had followed. They did not make it as far as Charlie had, receiving fire from bunkers spread out across the ridge. The enemy fired barrages of rockets at Alpha Company, which left one killed and several others wounded. Lieutenant Frank McGreevy ordered his platoon to make an assault with its machine guns spearheading the attack, but the enemy held its ground. He then ordered a withdrawal, covering it himself. The retreating stretcher bearers were attacked by enemy soldiers on both flanks as they made their way back down the ridge.

Alpha and Bravo had lost 17 and 19 men, respectively. Both showed 67 men on their rosters, half of what a normal rifle platoon should have. Replacements were sent in from Camp Evans, but most were not infantrymen, but rear-echelon men. The men had given Hill 937 another name: Hamburger Hill.

Beginning on May 16, the men of 3/187 spent 48 hours awaiting the arrival of the Currahees, the 1/506th, who were fighting their way up the hills south of Hill 937 to join them. There was talk from headquarters of relieving the 3/187th and continuing the attack with the 1/506th, but Honeycutt argued against it. Honeycutt believed that his company would be demoralized if they were not in on the final attack.

On May 18 a two-battalion attack was ordered, the Rakkasans from the north and the Currahees from the south. Charlie and Delta Companies, 3/187th, were stopped just short of the summit. A heavy rainstorm that dropped visibility to zero and left mud knee deep stopped them cold and they dug in where they stood. By this time, Alpha and Bravo Companies of the 3/187 had suffered 50 percent casualties and Charlie and Delta companies 80 percent. The next day, they were ordered to withdraw.

Ten artillery batteries pounded the top of Hill 937 on May 20 with 20,000 rounds and 272 airstrikes, dropping one million pounds of bombs and 152,000 pounds of napalm. The 3/187th, 2/3 Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and a company from 2/506th attacked together and were able to secure the hilltop by 5 PM. They found that most of the enemy had fled, leaving only a few soldiers behind to make a last stand. The U.S. troops had suffered 72 killed, 400 wounded, and seven missing. The number of NVA casualties would never be known, but the official body count placed their dead at 630.

U.S. newspapers carried Sharbutt’s account of the battle, which he called a meat grinder. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, Senator Edward Kennedy excoriated the Army for its attack on Hamburger Hill, calling it “senseless and irresponsible.” The Army was sending “our men to their deaths to capture hills and positions that have no relation to ending this conflict,” he said. Criticism of the war, although present since the start, increased significantly.

The battle drew to a close after 10 days of savage fighting. The Americans withdrew on June 5, leaving the mountain and the A Shau Valley to the enemy for the remainder of the war. Hamburger Hill was the last major battle between American and North Vietnamese forces in the Vietnam War.

On January 27, 1973, representatives of the United States, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and the Vietcong signed a peace accord in Paris that established a cease-fire. On March 29, 1973, the last of the American combat troops departed South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese soon violated the cease-fire. On April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese forces captured Saigon.