By William F. Floyd, Jr.

On January 30, 1968, eight battalions of North Vietnamese Army infantry infiltrated the city of Hue in South Vietnam. The NVA 6th Regiment secured the citadel on the north bank of the Perfume River, and the 4th Regiment seized the south side with its more modern buildings. Arriving in the city as part of the Marine Corps reinforcements were the 1st and 2nd Ontos Platoons of A Company, 3rd Antitank Battalion. In the days that followed, they would work together with C Company, 1st Tank Battalion, to furnish much-needed direct fire support to Marine riflemen. During the protracted urban battle, the Marines often paired the nine-ton M50A1 Ontos with the 50-ton M48A3 Patton tanks. The symbiotic partnership allowed the tanks to maneuver against the enemy target while Ontos furnished covering fire and vice versa.

Each had different strengths. Lt. Col. Ernest Cheatham, one of the commanding officers at Hue, liked the Ontos for its speed and maneuverability, whereas Lt. Col. Robert Thompson preferred the Patton tank for its armament and staying power. Over the course of the battle, the enemy would knock out three Ontos. The Ontos came in particularly handy because until the Marine Corps tanks received concrete-piercing fuses for their high-explosive ammunition, ground commanders were compelled to rely heavily on the Ontos’ 106mm antitank shells to knock down concrete walls as the Marines worked to clear the city of enemy forces.

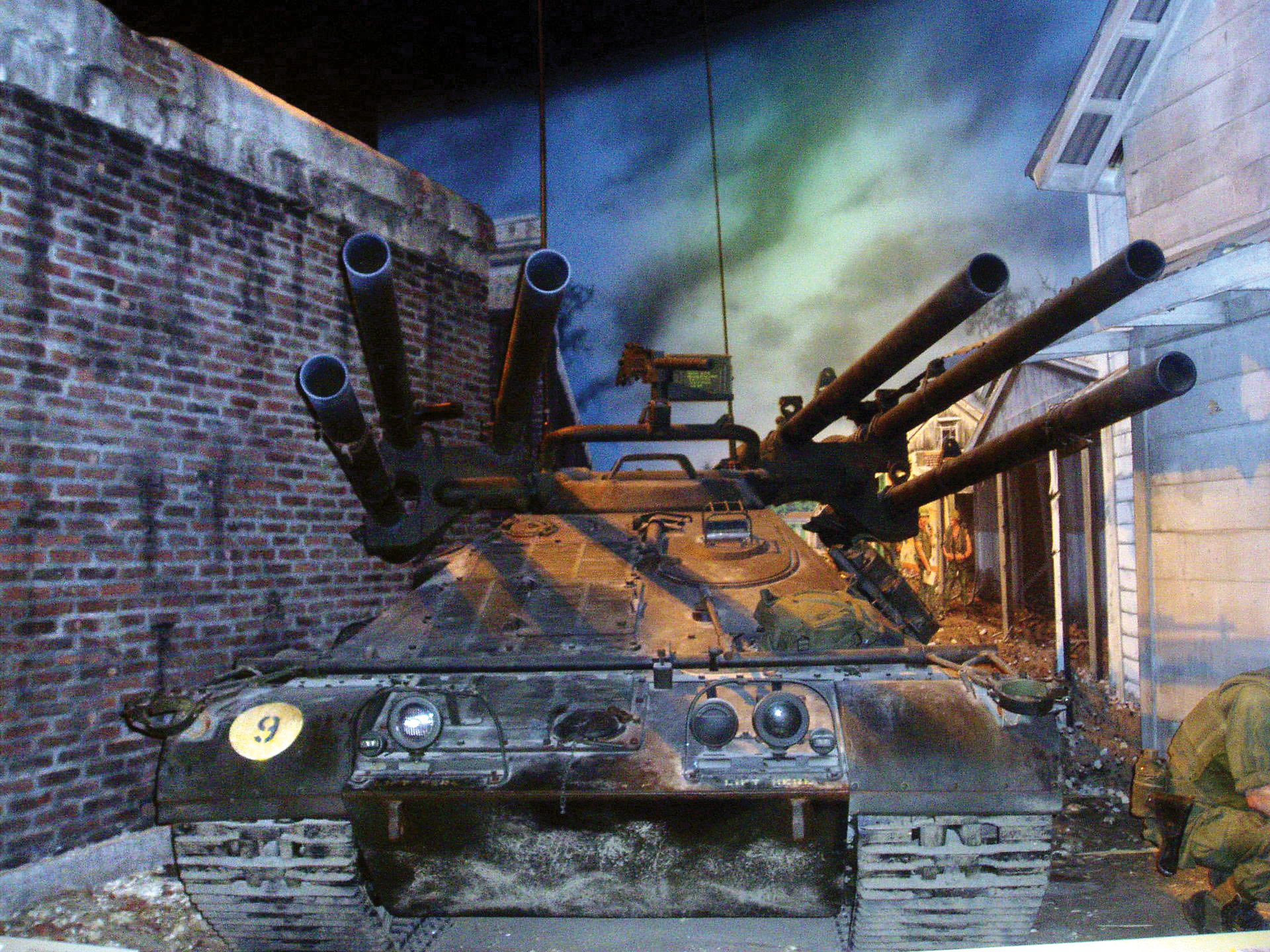

The U.S. Army traditionally has named tanks after famous American generals, but in the case of the Ontos officials feared that if they named such an odd-looking vehicle after a revered commander some Americans might be offended. The squat vehicle ultimately received the name Ontos, which means “thing” in Greek. With its tiny chassis and small turret supporting two strong cradles each of which supports three recoilless rifles, it is one of the most unique armored vehicles ever fielded by the American military.

Although the idea of the Ontos began with the U.S. Army’s requirement for a self-propelled antitank gun, it ultimately found a home with the U.S. Marine Corps where it was deployed in the service’s antitank battalions.

Following the conclusion of World War II, the U.S. Army was interested in developing vehicles that could counter opposing tanks, namely those fielded by the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies in Europe. Infantry battalions needed direct fire support, and tanks were simply too cumbersome for them. Therefore, the Army set out to develop a tracked platform with a powerful gun tailored to infantry battalions. Because the Army was intent on producing a higher proportion of its equipment for air transport, the service added a requirement that the new weapon system should be suitable for airborne operations.

U.S. Army officials began exploring the requirements for a small tracked antitank weapon at a two-day conference held in October 1948 on antitank defense at Fort Monroe, Virginia. They envisioned an antitank gun on a chasis somewhat similar to that of an American Weasel or a British Bren carrier. The conference findings, presented in a report the following year, outlined the Army’s vision for this new weapon system.

By March 1950 the idea had coalesced to the point that the Army’s Ordnance Technical Committee had embarked on the development of a 105mm recoilless rifle mounted on a self-propelled chasis that would furnish organic fire support to infantry battalions.

Following the outbreak of the Korean War in June of that same year, it became increasingly clear to the U.S. Army that infantry battalions needed mobile fire support as soon as possible given the heavy casualties that ground forces were suffering at the battlefront. Both Army Secretary Frank Pace and Army Chief of Staff General J. Lawton Collins championed the need for a new weapon system, known simply as the “infantry fighting vehicle,” which possessed heavy firepower. Shortly afterward, the Army met with representatives from Allis-Chalmers, Ford, and General Motors to discuss the concept. The Army subsequently received design ideas from each of the three companies.

The Detroit Arsenal unveiled a concept design on April 9, 1951. The initial design featured four recoilless rifles on a tracked chasis, but shortly afterward the requirement was changed to six recoilless rifles. By September 1951 the Army had begun calling the new infantry fighting vehicle Ontos. On October 6 Army Secretary Pace instructed Collins to make the Ontos pilot project a top priority.

The Ontos pilot vehicles were divided into two groups. One group was designated infantry assault vehicles, and the other group was designated infantry carrier vehicles. The Army soon selected Allis-Chalmers over the other two companies to design and produce the test vehicles. Because Allis-Chalmers did such good work on the pilot program, the Army selected it to manufacture the production vehicles, too.

The Army discarded the carrier model idea early in the process on the grounds that the infantry fighting vehicle was too cramped to accommodate mortar or rifle platoons. In addition, the Army decided that it would not use the existing M27 recoilless rifle because it lacked a spotting rifle necessary to extend its effective range. Instead, the service would incorporate the newer M40, which was capable of firing a fin-stabilized, high-explosive antitank projectile through a rifled barrel at an effective range of 1,480 yards.

In the meantime, the Army encountered challenges relative to the track and suspension systems that put the project a year behind schedule. As a result, field testing would not begin until March 1954.

The Marine Corps replaced the Army in November 1954 as the lead on the program with plans to conduct its own field tests. The Marine Corps commandant stated the following year that testing had been satisfactorily completed and that the service would soon begin purchasing the Ontos vehicles. Allis-Chalmers received a contract in August 1955 for 297 vehicles.

While the Marine Corps geared up to use the Ontos in 1955, the Army announced that it had found the Ontos unsuitable for use by field forces. The Army announcement had less to do with field test outcome and more to do with political infighting. The real reason was General Collins no longer supported the program. He held that the Ontos was not in keeping with the Army’s offensive fighting doctrine and that it would cut into the Army’s procurement of additional tanks. To support the Army’s case, officials identified a number of acute problems. They said that the Ontos was mechanically unreliable, lacked sufficient space for ammunition storage, and offered scant protection to the loader who would have to reload the recoilless rifles from outside the vehicle.

The Marine Corps accepted its first vehicle on October 31, 1956. The first model emphasized fire power over crew comfort. Its hull was derived from the T55/T56 series of tracked armored personnel carriers. A six-cylinder, in-line gasoline engine made by General Motors powered the vehicle, giving it 145 horsepower. The Ontos’s power source was coupled to a XT-90-2 transmission, which drove the front sprockets and turned the tracks.

The final version of the M50 required a three-man crew: driver, gunner, and loader. The gunner, who was the vehicle’s commander, had the ability to fire any of the six 106mm rifles in almost any combination with the help of a .50 caliber spotting rifle that was accurate up to 1,500 yards. The vehicle could carry 18 rounds of recoilless rifle ammunition. If necessary, the crew could detach two of the recoilless rifles for use on tripods by ground forces.

The M50’s shaped-charged, high-explosive antitank ammunition could penetrate the armor of any existing tank. In addition, its secondary high-explosive plastic ammunition round was capable of penetrating most armor as well as furnishing fire support for infantry units.

By the time the Vietnam War erupted, an antipersonnel round also was available. The 106mm antipersonnel round was a devastating weapon capable of inflicting horrific casualties on enemy infantry. The round contained 9,600 two-inch, winged steel darts called flechettes. Known colloquially as beehive rounds, the thousands of flechettes made an intimidating buzzing sound. The beehive rounds could be used like canister munitions or with a time fuse.

A .30- caliber machine gun was attached to the turret top. It was capable of firing either coaxially with the recoilless rifles using the interior fire controls or independently under the control of the commander/gunner. The M50 boasted 0.5-inch sloped plate armor for the hull and turret, however, its 3/16-inch floor armor made it highly vulnerable to enemy mines.

The commander/gunner of the Ontos had at his disposal a sophisticated gun-mount system that incorporated a number of subsystems controlling elevation, traverse, and firing. Each of the two weapons cradles held three 106mm recoilless rifles. Each cradle had its own hydraulic breech devices, electrical firing solenoids, and spotting rifles.

The Marine Corps wasted no time fielding the machines as they began rolling off the assembly line starting in October 1956. The 1st Marine Division was the first to form Ontos companies from disbanded antitank companies. The division equipped each of its new Ontos companies with 15 vehicles.

The Marines revised their offensive and defensive armor tactics to incorporate the Ontos seamlessly into battlefield operations. Although the Marine Corps believed that the Ontos would stand up well against small arms rounds and artillery shrapnel, it realized the vehicles were extremely vulnerable to enemy tank rounds. For that reason, the Marine Corps intended to allow the tanks to make contact with the enemy with the Ontos operating on the flanks. In defensive situations, the Ontos would lay in wait to ambush enemy tanks while the Marine tanks remained in reserve. Ontos companies were expected to hash out primary and alternate firing positions beforehand so that steady fire was maintained on the enemy.

The success of an Ontos in combat depended in large part on the skill of the commander/gunner. He relied on his periscope sights to identify a target. He then used the weapons control panel to arm the rifles and set the firing sequence for the number of rifles he wanted to use. After that, he aligned his reticles (the fibers in the periscope sights) according to an estimated range to target.

The Ontos was upgraded as part of the Marine Corps modernization program of 1963-1964. The upgraded M50A1 included a more powerful engine, solid-state radio, and azimuth indicator. The Ontos’s new Chrysler 361B V-8 engine provided 180 horsepower.

Marine Corps Ontos units saw their first action when the Marine Corps deployed in two civil wars: Lebanon in 1958 and the Dominican Republic in 1965. In these deployments, Ontos platoons were attached to battalion landing teams.

In the case of the Lebanon crisis, BLTs 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines and 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines went ashore at Beirut on July 15-16, 1958, as part of the 2nd Provisional Marine Force led by Brig. Gen. Sydney Wade. After securing the airport, Marine armor, including tanks, amphibious tractor, and Ontos moved into the city to guard a variety of locations, including the port, bridges, and the U.S. embassy. Altogether, two platoons totaling 10 Ontos participated in the operation.

The deployment to the Dominican Republic during that country’s civil war mirrored the Lebanon operation in many respects. The vanguard of the 3/6 Marines arrived by helicopter on April 26, 1965, and was followed quickly by heavier elements landed by the Second Fleet. Within 48 hours, tanks, amphibious tractors, and Ontos joined the battalion landing force in the capital city. When snipers fired on the Marines, the Ontos deployed for direct fire support, but the mere threat of such awesome firepower was enough to deter the hostile individuals.

As relations with Cuba began deteriorating in 1961, the U.S. Defense Department decided to establish a strong garrison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The garrison included a tank platoon and an Ontos platoon.

The most significant role for the Ontos during its existence was in Vietnam where it provided direct fire to Marine Corps riflemen fighting tenacious foe such as North Vietnamese regulars and veteran Viet Cong guerrillas. The Ontos arrived at Da Nang, South Vietnam, along with other vehicles of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade on March 8, 1965. Within a year’s time the tank battalions of the 1st and 3rd Marine Divisions also arrived in country.

Unlike the enemy the Marine Corps faced during the Korean War, the Vietnamese communists possessed superb anti-armor capabilities in the form of recoilless rifles and hand-held rocket-propelled grenade launchers, such as the formidable Soviet-made RPG-7. The Ontos vehicles proved capable of traversing rice paddies. This ability was a substantial morale boost to Marine foot soldiers slogging through the paddies who welcomed additional direct fire support.

The Marine Corps in Vietnam was deployed in I Corps, the northernmost of the four tactical zones of responsibility into which South Vietnam was divided. While the 1st Marine Division in the southern part of I Corps was heavily engaged in counterinsurgency, the 3rd Marine Division deployed along the Demilitarized Zone fought under conditions that on occasion were akin to conventional warfare.

In May 1967 the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines and 2nd Battalion, 26th Marines began Operation Hickory north of Con Thien. The Marines encountered well-entrenched enemy forces using bunkers and trench systems. Following the conclusion of Operation Hickory, the Marines of 2/9 went on the offensive. They were supported to good effect by Patton tanks and Ontos, which were used in a spoiling attack into the DMZ. Use of the Ontos, though, proved problematic because they often had to travel on roadways in the rugged country.

The Ontos also provided a much-needed morale boost by their presence during the six-month siege of Khe Sanh that began in January 1968. In anticipation that the North Vietnamese might at some point launch a human wave attack against the Khe Sanh airfield, Marine Corps Colonel David Lownds had 10 M50A1 Ontos vehicles to supplement his armor and artillery at Khe Sanh.

Lownds positioned the Ontos around his defensive perimeter where they stood ready to shred such an attack if it occurred. No human wave attack ever occurred at Khe Sanh, largely because the Marines succeeded in holding the low hills north of the base despite local attacks by the NVA against them during the early part of the siege. By failing to capture the hills to use for their long-range artillery, the NVA could never create the conditions it felt were necessary to successfully launch a major assault against the Khe Sanh airfield.

The Ontos may well best be known for its role supporting Marine riflemen in the streets of Hue during the 1968 Tet Offensive. Hue consisted of two sections. The newer section of the city, where the Military Assistance Command Vietnam compound and the South Vietnamese Army headquarters were located, was south of the Perfume River. The older section, located on the north side of the Perfume River, consisted of an 18th-century citadel built by the French.

The Marines first cleared the newer part of the city before turning their attention to helping the South Vietnamese Army retake the citadel. One of the flaws in the NVA attack on Hue was that it failed to seal off the roads leading into the city from Route 1. As a result, Marine Corps armored columns, which included Ontos vehicles, were able to quickly reach Hue. During the street fighting inside the city, groups of Marine riflemen often furnished covering fire for Ontos engaged with the enemy in order to prevent the vehicle from being struck by enemy recoilless rifle or RPG rounds.

The Marine Corps did not record its Ontos losses in the Vietnam War, but few occurred as a result of enemy fire. Nevertheless, Ontos that broke down remained in a state of disrepair because of a general shortage of spare parts. One of the most obvious and frequent problems was that their tracks wore out.

The Ontos’s role in the Vietnam War ground to a halt when the Marine Corps began withdrawing its ground forces in 1969. By that time the Ontos’s spare parts supply was nearly depleted. Ontos mechanics salvaged parts from disabled vehicles to keep others running. In an ironic twist, the Marine Corps donated its surviving Ontos to the Army, which had rejected the system. In 1971, the Marine Corps disbanded the last of its Ontos units.

By that time the Marine Corps had refocused its efforts on next-generation antitank guided missiles with which it began equipping its units in 1975. The Marines kept one Ontos in service at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, but its last year in service was 1980.