By Kevin M. Hymel

The green light lit up the inside of the Douglas C-47 Skytrain’s fuselage, and 20 paratroopers from Easy Company’s Stick 70, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division charged out the door. Twenty-year-old Private Bradford “Brad” Clark Freeman, the fifth man in line, exited and his parachute quickly popped open. In the intermittent light of the full moon, he could see a pasture rushing up at him. He counted five cows below before he hit the ground.

“It was a nice jump,” Freeman recalled. He noticed one of the cows had a white face and red body, reminding him of the cows on his family farm in Artesia, Mississippi. For a brief second, he thought he was home before remembering he was now in enemy territory with a war to fight.

As Freeman freed himself from his jump harness, he looked skyward and saw paratroopers jumping out of another C-47. Their parachutes blossomed, and the men drifted to the ground. One man landed by a nearby road. Freeman rushed over and discovered it was his friend Private Lewis Lampos from Georgia, who slept across from him at their Aldbourne, England, barracks. Lampos had broken his leg. Freeman gathered up Lampos’s parachute and hid it in the woods then dragged him into some bushes. He briefly treated Lampos’s leg and told him if any vehicle passed by to shoot the driver. Then he took off to find more paratroopers as Lampos cursed after him. “They told us if you couldn’t help a wounded paratrooper,” explained Freeman, “you had to move on.”

Freeman eventually joined a mixed group of paratroopers led by Lieutenant Richard “Dick” Winters. When Freeman mentioned that he thought he had landed on his farm, the other soldiers ribbed him. Sergeant William Guarnere repeatedly asked him, “What makes your big head so hard?”

They made their way through fields and high hedgerows, where Freeman eventually picked up an M1 Garand rifle, which he preferred to his folding-stock carbine. “It wouldn’t shoot far enough,” he said of his carbine, “but it was a good street fighter.” As the sun rose, they passed a field filled with captured Germans. Sergeant Don Malarkey, who was part of the group, started talking to one of the prisoners. “Malarkey and him had known each other from Oregon,” said Freeman.

Winters assigned Freeman and a few other paratroopers to guard a crossroads near the Brecourt Manor farm, where Winters and elements of 2nd Battalion would later take out four German artillery pieces. Freeman spent the rest of D-Day at the crossroad. Considering the action around him, his day was relatively quiet. The Germans never assaulted his checkpoint, nor did he see any 4th Infantry Division soldiers coming up from Utah Beach. “Every once in a while, someone would get a prisoner,” he recalled, “but we were moving around and really didn’t see many.” He did hear Navy shells soaring over his position as they screeched toward targets farther inland. “Those two or three shells made a big racket,” he recalled.

Freeman was the only member of the company from Mississippi. Raised just west of Columbus by Methodist parents, he was the youngest of four boys: Earl, Herb, Glover, and Carry. As a child, he sometimes played with a girl named Willie Gurley, but as he got a little older, his parents put him to work. “When I was 11, I got my Social Security number and I worked with [Earl] measuring cotton,” he explained. By high school, he and his brother Carry enjoyed reading about world events, especially Russian and German paratroopers. “We thought we’d like to be paratroopers.”

The two put their interest into practice one day when they grabbed a visiting neighbor’s umbrella and ran to the barn. Climbing up to the loft, they opened the umbrella and jumped. The umbrella immediately collapsed, and the two crashed to the ground. “We ran into the woods until our mother called us back to milk the cows,” said Freeman. “Nothing was said about it.”

Freeman was swinging on a neighbor’s swing with their young daughter one day when the girl’s mother came out to say that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and that he should go home. It was December 7, 1941, and Freeman was only 17. “I didn’t know what was going on,” he recalled.

As the country went to war, Freeman attended Mississippi State College in Starkville, signing up for the draft when he turned 18 in September. “I figured if I joined the Army,” he said, “I could finish that year of school.” When the semester ended, he was sworn into the U.S. Army on December 12, 1942, and four months later he reported to Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, for induction.

While Freeman joined up, his four brothers took on various wartime careers. Earl had spent four years in the Army before the war and had gone to work with the Civilian Conservation Corps at Camp Shelby. Herb caught a thorn in his eye while cutting bodark hedges and was ineligible for service. Glover, who had played football for Southern Mississippi State, joined the infantry and served in Greenland and Iceland before transferring to England, where he took classes at Oxford University. Carry, who had jumped out of the barn with Freeman under the umbrella, earned an officer’s commission in the 11th Airborne Division. He jumped into New Guinea and fought in the Philippines in the Pacific Theater.

After Freeman’s induction, he traveled to Fort McClellan, Alabama, for basic training. The Army issued him a uniform but had no size six boots, so he began training in his Sunday shoes. Once he graduated, a contingent of paratroopers came through the camp looking for volunteers. Freeman, considering himself a veteran paratrooper since he had jumped under an umbrella, eagerly joined and headed off to Fort Benning, Georgia, to become part of the airborne.

He joined Colonel Ducat M. McEntee’s 541st Parachute Infantry Regiment, training at Fort Benning. All candidates had to make five jumps, including one at night, to earn their jump wings. Despite the tension and anxiety of jumping out of a plane (or perhaps because of it), Freeman often jumped with a plug of Bloodhound brand chewing tobacco in his cheek. On one jump, he leaped out of the aircraft, but one of the candidates refused to jump. “They took him away,” recalled Freeman. “That was the last time I seen him.”

On his third jump, Freeman’s parachute deployed but his leg got caught in his harness. As he floated to Earth, an instructor shouted up to him how to disentangle his leg. He wrestled himself free before hitting the ground and landed safely except for one thing: “I swallowed my chewing tobacco.”

For the night jump, on October 30, 1943, three C-47s packed with paratroopers took off, but one aircraft crashed, killing 14 men. “I didn’t know them, but they gave me 14 days to go home,” said Freeman. He wanted to be home for Thanksgiving, November 25, but his 14-day leave expired on Thanksgiving Day, forcing him to return to duty before the holiday arrived. Upon his return, he received his coveted wings.

The training continued with Freeman making it through the daily grind of hikes and calisthenics. Despite the regiment’s excellent performance and high marks, it was part of the Army’s strategic reserve, not slated for overseas duty. Freeman wanted to fight. Fortunately, the 11th, 82nd, and 101st Airborne Divisions needed paratroopers for combat. Freeman was picked for Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s 101st, which had already departed for England in September, three months earlier.

In February 1944, Freeman, promoted to corporal, boarded a converted cruise ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean for England. He enjoyed standing on deck and watching flying fish jump alongside the ship. The trip was not all smooth. When the ship hit a storm with heavy seas, the crew sealed all the hatches. “We felt like we were being smothered to death,” Freeman recalled. When the ship finally arrived in England, he and about 11 other paratroopers disembarked onto a ferry boat.

A lieutenant from Easy Company in Colonel Robert Sink’s 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment arrived in a jeep to bring the men to camp. Freeman did not like the looks of Lieutenant Dick Winters, the leader of Easy Company’s 1st Platoon. The two sat across from each other and, as Freeman remembered it, “We looked at each other like two bulldogs who wanted to fight.” Winters stood up, and Freeman, thinking they were about to grapple, started to get up. “Just sit back down,” Winters told him. “As you were.” Freeman sat down, and the two talked. He had a new respect for Winters.

Winters brought Freeman and the other new paratroopers to their new barracks in Aldbourne, headquarters for the 506th. They arrived at night, when the entire camp was blacked out, with no street lights and windows draped by heavy black curtains.

The next morning, Sergeant Guarnere marched the new paratroopers to the company commander, Lieutenant Thomas Meehan, who had taken command from Captain Herbert Sobel three months earlier after a handful of sergeants threatened to turn in their stripes instead of serving under Sobel. After a few words, Meehan dismissed all the men except Freeman, telling him the company had no room for a corporal and that Freeman would be reduced to a private first class. Freeman did not complain. “I liked being a private,” he reflected. Meehan assigned him to Sergeant Don Malarkey’s 4th Squad in Lieutenant Winters’ 1st Platoon. Freeman came to like Malarkey. “He was a good fellow all the way,” he said.

For the next four months, Freeman trained with his new unit. He participated in parachute jumps and field maneuvers. He fired mortars and his folding stock M-1 carbine on the rifle range. As the company’s only paratrooper from Mississippi, the men enjoyed his accent. “They liked my Southern brogue,” he said. Fellow Easy Company paratrooper Corporal Walter Gordon had lived in Mississippi and Louisiana but claimed Louisiana as his home.

During one rifle inspection, Winters, as Freeman remembered it, “tried a little something on me.” He took Freeman’s rifle before Freeman had a chance to open its bolt. Winters noticed the closed bolt and tried to hand it back to Freeman, but Freeman refused. He knew never to accept a rifle during inspection that might be loaded. “I stood there until he opened the bolt and shut it,” recalled Freeman. “He done it right.” But Winters was not finished. “He asked me if they gave me a razor and to get the peach fuzz off my face.”

That was the moment Freeman and Winters developed a friendship. “We got to be buddies,” he recalled. “We was raised alike and had to work when we was children.” Winters eventually offered to send Freeman to Officers Candidate School, but he declined. He had found his niche as a private and was proud of it.

One cold night, Freeman broke the rules by starting a fire for his fellow paratroopers. Guarnere caught them and demanded to know who started the fire. Freeman spoke up. “I was cold.” Guarnere did not respond, but the next day Freeman found himself on guard duty, standing in the cold he so hated.

On the last day of May, the 506th transferred to an airfield near the village of Upottery in southwestern England. The men moved into tents and spent the next several days learning about their D-Day objectives. Easy Company was to drop near the town of St. Marie du Mont and both eliminate a German garrison and seize Causeway No. 2 on Utah Beach, clearing the way for the amphibious forces of the 4th Infantry Division. When a storm swept through the English Channel, the men’s jump date, set for June 4, was delayed 24 hours. “The delay didn’t bother me,” said Freeman. “It was delayed before we put on our jump suits.”

The next day, Freeman and his comrades suited up for their combat jump. As part of the company’s mortar unit, Freeman strapped an 18-pound mortar baseplate to his chest. “Malarkey had six rounds for the mortar and others had six rounds too,” said Freeman. Unlike the depiction on HBO’s Band of Brothers miniseries, Freeman never received a British leg bag nor streaked his face with black cork. He did keep a small Army-issued Bible. “That was the year that [President Franklin D.] Roosevelt gave us a little Bible.”

Freeman was fastening some Bangalore torpedoes, used to blow up enemy obstacles, onto Guarnere when a fellow paratrooper came by, selling watches. Guarnere, who had just found out that his brother had died fighting at Monte Cassino in Italy, became furious and chased the man off. Guarnere would later earn the nickname “Wild Bill” for his fighting intensity, brought on by his brother’s death.

The men gathered around Lieutenant Lynn “Buck” Compton, the commander of 2nd Platoon, who wore the number “70” on a piece of cardboard around his neck, designating their C-47. They then climbed into their aircraft. Freeman, so weighed down with equipment, needed British soldiers to help him up through the door. Twenty paratroopers packed onboard.

The C-47 took off in the dying light of June 5, 1944, and joined the fleet of 87 aircraft bearing the division for its flight across the English Channel. “It was silent,” said Freeman about the trip. “No one was saying nothing.” As the aircraft passed over the Channel Islands and French coast, enemy fire broke the silence. German antiaircraft streaked into the night sky. “You could hear it.” Then the red jump light lit up. The men stood up and waited for it to turn green. The plane screamed above Normandy at 200 miles per hour, 100 miles per hour faster than their normal jump speed.

In the confusion, the men failed to check each other’s equipment. Still, when the green light lit, Freeman jumped out and landed safely in a pasture. He spent D-Day protecting the intersection near Brecourt Manor.

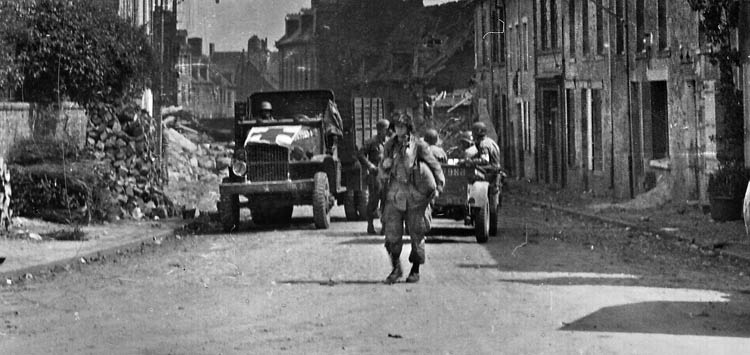

Six days after D-Day, on June 12, Easy Company helped spearhead an attack into the vital city of Carentan, whose capture would unite the troops fighting on Omaha and Utah Beaches. Freeman and his fellow mortarmen set up their weapons southeast of the town before dawn and commenced firing. “That was the most firing we had ever done,” he recalled. As the men dropped mortars down tubes and adjusted their fire, Colonel Sink came by and told them to hold their fire. A Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter aircraft had targeted Carentan’s railway station. “The plane flew right over us and went across and came back and blew up the railroad with a 500-pound bomb,” said Freeman.

Once the P-47 departed, the men returned to firing their mortars. When ammunition ran low, Sink personally resupplied them using his own Jeep. Once the infantry successfully captured Carentan, the mortarmen followed. “We weren’t shot at,” Freeman recalled, “although some shells did come through.” He thought the town looked pretty intact, except for one building that lost a wall, making the rooms visible. “It was like Mississippi State’s old dormitory,” he said.

On June 28, the 83rd Infantry Division relieved the 101st, and the men of Easy Company made their way to Utah Beach for the trip back to England. As they prepared to board a Landing Ship, Tank (LST), Malarkey asked Freeman to help Private Alton Moore get an Army motorcycle into the ship. Moore rode the motorcycle up the LST’s ramp, and Freeman pulled it onboard to safety. The men would spend their free time riding the motorcycle over the English countryside.

Back in Aldbourne, the men trained for their next jump. During one training jump, Freeman banged his knee, causing it to swell with fluid. One of the company medics, Private Eugene Rowe, drained it every few days. Freeman was taken off jump status and waited tables at the officers’ mess while his knee healed. During his recovery duties, Freeman ran into Private Lampos, the paratrooper who broke his leg on D-Day. Lampos was still angry and, as Freeman remembered it, “he gave me a good talking to.” Once he finished venting, Lampos forgave Freeman. “We was good friends again after that.”

Easy Company’s next mission came on September 17, when the men loaded into C-47s bound for the Netherlands: Operation Market Garden. British Field Marshall Bernard Law Montgomery planned to drop three airborne divisions into the country to protect a series of bridges along a single road that his army group would use to flank the German army on its right. The 101st Airborne was assigned to capture the Dutch cities of Eindhoven, Son, Veghel, and Grave. “We got all the ammunition we could carry,” said Freeman about preparing for the drop.

The planes took off that morning and flew across the Channel. Freeman and his comrades spent the journey watching the other C-47s flying alongside. For protection, P-47 Thunderbolts flew below the troop carriers, Lockheed P-38 Lightnings flew above, while North American P-51 Mustangs flew alongside. As they reached the Netherlands, German flak towers opened fire on the airborne armada. Freeman saw a P-38 dive on one tower. “He came straight down and turned up,” said Freeman. The Lightning poured machine-gun fire into the tower. “He stopped that gun from shooting ack ack.”

When Freeman’s aircraft reached its drop zone, he lined up and jumped out with the rest of his stick. “We landed, gathered up, and went to our areas,” he said. As he headed off, he witnessed two gliders crash into each other some 50 feet above him. “They were up above us,” he remembered, “high enough to turn bottoms-up and backwards, flipping over.”

As the paratroopers reached Son, their first objective, grateful locals swarmed them. “They would give you anything,” said Freeman. He watched as a small boy ran up to Private Joseph D. Liebgott and asked to see the bazooka strapped to his back. Before Liebgott could react, the boy pulled the bazooka’s trigger, firing a round straight down into the middle of the street. Fortunately, the round didn’t explode.

The town’s liberation unleashed strong feelings. Some expressed joy at being delivered from four years of Nazi occupation; others chose to vent their anger on their fellow citizens who had collaborated with the Germans. Some of the women offered apples to their liberators, while others were punished for fraternizing with the Germans. “We could see down the street people cutting the hair off the women,” said Freeman.

Easy Company raced for the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal, but the Germans managed to blow it up before the paratroopers arrived. The men continued to Eindhoven, encountering some German fire as they neared the northern approaches. The next day, the British Army arrived. As infantry, tanks, and vehicles passed the paratroopers, Freeman could hear a conversation on a radio from one of the command vehicles. “There was talk about battle,” he said. Suddenly, the British stopped advancing and huddled into groups. Freeman asked an English soldier what was going on. The man explained, “A spot of tea, old bloke.”

That night, word passed down that a German tank was on its way to their area. “We went to meet it,” said Freeman. As the men advanced, a Luftwaffe aircraft flew over and dropped flares, illuminating the area. “We froze like a fence post.” They could not see any tanks, so once the flare faded the men returned to camp.

With Son and Eindhoven captured, the 101st’s mission changed from capturing bridges to defending the single road leading to the city of Arnhem, where British 1st Airborne Division paratroopers desperately fought to capture the vital bridge over the Lower Rhine River (the river runs south to north). The Germans repeatedly cut the road, attempting to disrupt Allied progress, earning it the title Hell’s Highway. “We’d open up a road,” explained Freeman, “then the Germans would attack and we would have to go back.”

One day, the Germans attacked the highway from the east while Winters led some Easy paratroopers from the west. The two sides engaged at a section of double highway divided by a concrete drainage ditch and covered by a bridge. “I was not very far from it,” said Freeman. “They looked up and saw each other on each side.” From his vantage point, he could see the Germans trying to use the ditch and bridge walls to their advantage. “They was trying to shoot through it and make it ricochet,” he said, adding, “They had a tank battle right behind us.”

On September 20, Freeman and a platoon from Easy joined three British tanks and about 100 men from regimental headquarters for the drive to Nuenen, about four miles northeast of Eindhoven. The men made it through the town, but as they reached the outskirts German tanks and infantry attacked. “They had a tank sitting back in one of the places,” said Freeman, “and one of our boys tried to get one of the [British] tankers to shoot.” This would have been Sergeant John Martin, who climbed onto a British tank and warned the tank commander about the enemy threat, but he was ignored. The enemy tank emerged from its hiding place and blasted the British tank. “I wasn’t too far behind.”

A tank battle broke out with the British getting the worst of it. The paratroopers pulled back. Freeman ran past a knocked-out British tank. “It was still smoking and popping and burning,” he recalled. “That was very unpleasant and bad smelling.” The fighting outside Nuenen was some of the worst Freeman experienced during the war. “It was a pretty rough time.”

Easy Company and the rest of the 101st Airborne continued to fight for Hell’s Highway until Arnhem fell to the Germans on September 25, trapping hundreds of British paratroopers on the north bank of the Lower Rhine. A week later, on October 2, Freeman and his comrades were trucked north and took up positions on the southern bank of the Lower Rhine, west of Arnhem and about equidistant between the ancient towns of Opheusden and Driel, an area known as “the Island” since it was cut by the Maas River to the south.

Farms separated by dikes and wooded areas comprised the Island. The men dug foxholes into the dikes for protection, just like they had done in France’s hedgerows. Here, for almost two months, the 506th clashed with German patrols on the Island or with groups that crossed the river at night. Some of the fighting was so close the two sides tossed hand grenades across the dikes at each other.

On October 5, Freeman joined a patrol led by Sergeant Malarkey through a wooded area, where they set up a camouflaged observation post. Freeman spotted seven Germans with two German Shepherd dogs depart a house and head out on their own patrol. “They had been down at that house goofing off,” he explained. “We were scattered out in the woods.” When the Germans unknowingly reached the paratroopers, Freeman shouted out “Achtung!” They stopped, and the paratroopers quickly surrounded them. While the other paratroopers kept their rifles trained on the Germans, Freeman focused on a different threat. “I never pointed [my rifle] at the Germans, I pointed it at the dogs.” The Germans went off with their captors, but the dogs did not join them. Speaking of one of the animals, Freeman remembered, “He didn’t follow us either,” said Freeman. “He was a big dog.”

The Americans led their prisoners to the edge of the woods, which opened up to flat fields and swamps near the river. They worried the enemy would fire on them while they crossed the open area. “What are we going to do now?” Malarkey asked. “We’ll get in the middle of them,” Freeman answered. “If they kill us, they’ll kill their men too.” The men arranged the Germans around them and continued on their journey. It worked. “We weren’t shot at.”

While Freeman helped bring in the German prisoners, Winters led a clash with an entire company of Germans dug in at a crossroad of two intersecting dikes. “He just took so many and left the rest of us to secure the dike,” recalled Freeman. When Freeman finished with the prisoners, he manned a position near a jelly factory. “We had a quarter mile each [to cover], and I remember looking across the water.” Winters led his attack on the Germans while Freeman defended his post. “We were on the left,” Freeman remembered. “We had to move up and back and got fired on, but not much.” When it was over, the other paratroopers told Freeman about Winters’ final charge to eliminate the enemy. “I heard that he ordered ‘fixed bayonets.’” The successful attack earned Winters a transfer to battalion staff.

After the crossroads fight, the Germans brought in a railway gun. Freeman recalled seeing it roll into his area. “The Germans would take this big gun on the railroad, roll it in and roll it back,” he said. “It took two little cars to take the gun, so they’d have Germans riding on the side.” The gun never fired on Easy Company, so the men never fired on it. “We didn’t bother them.”

Two weeks after the crossroads battle, Freeman and 17 other paratroopers were picked for a possible suicide mission. On the north bank of the Lower Rhine, some 125 British paratroopers, several members of the Dutch Resistance, and a handful of American pilots remained surrounded by German forces west of Arnhem. To rescue them, British Lt. Col. David Dobie devised Operation Pegasus, a river crossing in the dead of night on October 22. Colonel Sink agreed to the operation and picked Lieutenant Fred “Moose” Heyliger, Easy Company’s new commander, to lead it.

The men trained with boats and took swimming lessons. Freeman took a few lessons but told Lieutenant Colonel Clarence Hester he simply could not swim. “Hester got into it with me,” recalled Freeman. “He told me no boy from Mississippi couldn’t swim.” Freeman told him that back home the only watering hole on his farm was where the cows drank and relieved themselves. “It wasn’t a good place to swim,” said Freeman. He finally told Hester, “If somebody throws me in water over my head I won’t drown, I could dog paddle.” Hester told Freeman he should teach the other men the same.

On the night of October 22, the men pushed off and paddled across the river. As they crossed, the Germans on the high ground opened fire with heavy weapons and hit Colonel Sink’s quarters on the southern bank. The boats touched down on the northern bank, and Freeman jumped out, then grabbed the boat so the current wouldn’t pull it away, and also so “I wouldn’t get caught.” The British and their allies climbed into the boats and pushed off. Most of the troops that approached Freeman were Polish paratroopers. As many men as possible loaded onto the boats and headed south, leaving Freeman and his comrades alone on the north shore.

When the boats returned, Freeman, his fellow Easy Company men, and the last Allied fighters climbed onboard. As they made their way back, the rescued paratroopers, wanting to help, started paddling with their rifle butts but the splashing became too loud. “We told them they couldn’t do it,” Freeman explained. When asked if he was ever worried about being stuck on the north bank, he said, “We got to where we were used to it.”

After almost two months in the Netherlands, Freeman and his fellow paratroopers boarded trucks and headed to an old French camp in Mourmelon-le-Grand, France, for rest and refitting. Freeman was glad to be out of the mud and clean for a change. He received a five-day pass to Paris, but the City of Light did not appeal to the Mississippi farm boy. The urinals in the public bathrooms consisted of a trough that ran out to a street gutter. They reminded him too much of the troughs for the cows (for the same purpose) back home. “I didn’t see anything I liked about Paris,” he recalled. “I didn’t like Paris at all.” He returned to camp and spent his time either watching his friends play cards and shoot dice or cleaning his rifle and mortar.

The relaxed atmosphere did not last long. Two weeks after arriving in Mourmelon, on December 17, Freeman and his comrades were put on 24-hour alert. The Germans had broken through the American lines in Belgium and Luxembourg. The 101st Airborne was needed for its toughest campaign yet, fighting surrounded in snow and ice against a resurgent German army.

When word reached Freeman in Mourmelon-le-Grand, France, that the entire 101st Airborne Division was being put on 24-hour alert for movement to the front, he was neither surprised nor shocked. “They told us to go, so we went,” he said.

The Screaming Eagles scrambled to organize. “They got everyone out of Paris that they could find,” Freeman recalled. The men in Mourmelon at least had their weapons. “We were supposed to turn in all our guns,” he explained, “but no one did.” The commanders and noncommissioned officers ordered the men to prepare to move out. “We got ready, but we didn’t have much ammo.” In the confusion, Freeman spotted a Lieutenant Bush, with whom he had served in the 541st Parachute Infantry Regiment back in the United States. Freeman hollered to him, asking what unit he was with now. “I don’t know!” Bush hollered back. “I haven’t been placed yet!”

The men boarded trucks to take them into combat, having no idea where they were headed. Freeman stood in the back of his truck, near the tailgate, holding onto a strap for balance, hoping it wouldn’t break. “We were packed so tight, no one even thought about moving,” he explained. “You didn’t even move your feet.” The ride was cold and rough, with the men adapting to arriving to combat not in aircraft but in trucks. “If they went up a hill, you leaned forward,” he said. “If they went down a hill, you leaned back just a little bit.” Every time the truck sped dangerously around a corner, Freeman thought, “This is it!”

After an entire day of driving through light snow and freezing rain, the trucks stopped outside the small town of Bastogne, Belgium, where the men piled out. “I was tired when we stopped,” said Freeman, “and was glad to get out.” As they began their march into the town, a hoard of wounded and worn-out Americans, walking the other way, warned them of what lay ahead. The men were from the 28th Infantry Division and several armored units that had fought for three days to delay the Germans in their offensive toward Bastogne. Now they were spent.

One of the soldiers, a six-and-a-half-foot-tall sergeant, told the paratroopers they risked death if they advanced, “since the Germans were shooting everyone,” Freeman recalled. Private Edward “Babe” Heffron, a rather short paratrooper from Philadelphia, “told him to just go wherever he was going to and we’d stop it.” Freeman appreciated Heffron’s attitude. “He was a funny guy.”

Easy Company passed through Bastogne, where Freeman heard gunfire. “This is it again,” he said to his fellow paratroopers. The men marched to a crossroads and up a hill, occupying the Bois Jacques (Jack Woods), which overlooked the village of Foy. With 2nd Battalion in reserve, Easy occupied the southern section of the woods. Freeman dug a mortar pit about four feet deep near battalion headquarters. Captain Richard “Dick” Winters, Easy Company’s original combat commander whom Freeman greatly respected, had been transferred to battalion staff and occupied a headquarters foxhole. “Winters wasn’t too far,” said Freeman.

On December 20, Easy moved up to the front line on the northern edge of the woods. Freeman communicated with Lieutenant Dike through two-way phones, always ready to drop mortar rounds wherever Dike requested. To keep dry, Freeman and his fellow mortarmen draped tarps over their foxholes. For warmth, they burned gasoline-soaked paper in their canteen cups inside their covered holes. “Whenever you blew your nose,” he recalled, “it was soot.”

Soon after Easy’s arrival, the Germans completed their encirclement of Bastogne. To them, Bastogne was a vital communications link, a “road octopus,” in the words of the 101st’s logistics officer, Lt. Col. Howard Kinnard. To the men of the Screaming Eagles, being cut off meant no more reinforcements, no supplies, and limited medical care for any wounded. Freemen spent the siege hungry, cold, and tired. Hot chow, when the men could get it, consisted mostly of hard bread and pea soup served from a five-gallon tank. “That was a good meal,” said Freeman, “a few peas and some bread.” The men had to leave their foxholes, alone or in pairs, to fill their cups. One night the Germans shelled Easy’s position, hitting the hot food supply and destroying it right after they had eaten. “It blowed up!” recalled Freeman, his disappointment at losing the supply still sharp after 75 years.

When the skies cleared on December 23, two American Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes from the U.S. IX Air Force swooped out of the sky and strafed the German lines. “We were waving at them,” Freeman recalled, “but the bullets kept coming.” The aircraft rounds crossed into the American lines, kicking up snow around Easy Company. “Both those planes put bullets all around us,” he said, but no one in the company was hurt. Pfc. Silas Harrellson, a replacement, was out relieving himself when the fighters attacked, and he dashed back to Easy’s lines. “He came back holding his britches at half mast,” said Freeman, “and he dived into his foxhole head first as a bullet hit the edge of his hole.” The scene was special to Freeman. “That was the time I was scaredest and laughed the most.”

Freeman heard a rumor that Colonel Robert Sink, commander of the 506th, had devised an answer to the friendly fire from an unlikely source. “I heard [that] Sink called one of the Red Tails,” said Freeman, referring to the famous Tuskegee Airmen, the African American pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group, whose North American P-51 Mustang fighters sported a distinctive red vertical stabilizer. “Sink asked him how long it would take and he said about an hour, and those boys came in, knocking the snow off the pines.” However, since the famed Red Tails were flying cover for bombers in Italy during the Battle of the Bulge, these aircraft must have come from a different unit, such as the 360th Fighter Squadron, whose crews also painted their vertical stabilizers red.

The Germans attacked Easy Company on December 24, Christmas Eve. Freeman spent the battle dropping mortars on the attacking enemy. The Germans spent the rest of the siege content with firing an inaccurate artillery piece from Foy. “They covered the gun with sheets and things so you wouldn’t know anything about it,” explained Freeman. “It would hit in the valley, and we could see it blow up the snow. It didn’t bother us.”

Later that day, the men listened to Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe’s Christmas message to the troops. McAuliffe was in temporary command of the division, Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor having departed for the United States a few days before the German attack. In his message, McAuliffe extolled the exploits of the 101st and its dogged defense of Bastogne. He also revealed that he had replied to a German surrender request with a single word: “NUTS!” The men loved it. “I thought it was mighty good,” said Freeman. “He let us know that we weren’t giving up.”

Throughout the siege, Freeman never worried that the Germans would break though. “We didn’t ever see any tanks,” he said. A few days after Christmas, he walked into Bastogne with a few other paratroopers. As he left, he turned around and was shocked at its transformation from the neat little town he had seen on December 19. “Bastogne was torn up and bombed,” he reflected. The siege was taking a heavy toll. As they continued on their way, one of the paratroopers shot himself with his weapon. “He was fooling with his gun, and it went off.” This may have been Corporal Donald Hoobler, who shot himself in the leg with a captured Belgian-made .32 automatic pistol on January 3, 1945. The pistol had no safety switch.

Once the 4th Armored Division of General George S. Patton’s Third Army broke the siege from the south on December 26, Easy Company, as well as the rest of the regiment, pushed north to retake the town of Foy on January 13, 1945. Two days later, at 4 am, Freeman was digging a new foxhole for his mortar somewhere between Bastogne and Foy when he got the word to move out. “By the time we got to the good dirt, from where we could keep the snow from melting,” he said, “they told us we were going in again.” Freeman was exhausted, and his clothes were soaking wet from digging.

The men headed up a road with only their weapons and ammunition. “We didn’t know anything, and we were just messing around,” he recalled. Then a large group of Germans appeared, walking south. Fortunately, they had already surrendered and were heading to the American rear, so Freeman and his comrades gave them the right of way. “I had to stand on the opposite side of the road while they passed.”

The 506th was attacking Noville, about a mile north of Foy. Freeman and Private Ed Joint were ordered to help clear the town of snipers once the company had captured it. As they headed through a wooded area near Recogne, northwest of Foy, they came across a horse with a broken leg. The two men were debating the most humane way to put it down when Pfc. John Sheehy walked up and shot the horse in the neck. It went down, but the bullet did not penetrate the hide. “Another paratrooper shot the animal in the head with his M1 Garand rifle,” said Freeman, “killing it and putting it out of its misery.”

Suddenly, two German Nebelwerfer rockets (known to the Americans as “Screaming Meemies” for their intense whistle) screeched toward them. “It was just howling when it came in,” said Freeman. “I got hit in the leg.” Shrapnel penetrated his right knee. “It didn’t get the bone, but my foot would drag.” Joint also went down with shrapnel in his arm. Easy Company medic Eugene “Doc” Roe rushed over and started cutting off Freeman’s pants leg to treat his wound. “Deal with Ed! Deal with Ed!” he demanded. “Don’t deal with me!” Freeman felt the stinging cold as his skin was exposed to the raw air. Roe patched up both men and ordered them to the rear.

As the two paratroopers limped away, another salvo from the Screaming Meemies screeched in. Freeman ducked between two dead mules to escape the explosion. Once the snow and dirt settled, the two paratroopers continued their journey. “I could still walk, but I couldn’t control my foot,” he said. Eventually, a jeep arrived and took them south to Bastogne. Freeman’s war was over.

From Bastogne, Freeman was put on a boat bound for a hospital in England, where he spent three months in recovery. Surgeons repaired his right leg and kept it stretched so it would not heal shorter than his left. “I walked on my toe for a long time,” he said. “It was sticky; I felt like I had a pin in it.” Once he recovered, he caught up with Easy Company on April 7, 1945. By then the company occupied the west bank of the Rhine River, across from Düsseldorf. It would soon head east by train and later by DUKW amphibious trucks through southern Germany.

On May 4, Easy Company occupied the German town of Berchtesgaden, home of Adolf Hitler’s mountaintop retreat, the Berghof, with its famous “Eagle’s Nest” lookout. With the Americans at the far end of a flimsy and unreliable supply line, food ran low. Freeman and some of his fellow paratroopers remedied the problem by picking up shotguns. “We went hunting, and we fed ‘em good,” he said. “We cooked venison, quail, and wild guinea fowl.”

On May 8, Germany formally surrendered to the Allies. “I was just glad it was over with,” Freeman said. Everyone started tallying their combat points, hoping to reach the magic number of 85. Soldiers earned points for time in service, battles, medals, and their number of dependents. Freeman had accumulated 126 points. He would not remain in Europe long.

Freeman ended the war with the rest of the company in Zell am Zee, Austria, where the men trained, relaxed, drank, and entertained themselves. One day some of the men planned to make a parachute jump into the town’s mountain lake to test new quick-release harnesses. Freeman was supposed to make the jump but begged off. “Some fellah wanted to jump,” said Freeman, “so I gave him a good blessing.” Freeman was training to fight in the Pacific when he learned about the atomic bombs dropping on Japan. “I was glad,” he said, “but I didn’t celebrate.”

With no more combat training needed, Freeman was assigned to shipping horses into Germany. He loaded horses into boxcars and rode with them to their destinations, where he passed them off to German civilians. “I didn’t know where the horses were going,” he said. On one delivery, Freeman opened the boxcar door and found himself in a huge railroad yard. Surprisingly, French soldiers greeted him. “We were in their territory,” he recalled. “They got us off and notified the 101st.”

With high-point men having already departed, what was left of the regiment headed south to the French coastal town of Marseilles to sail for the United States, but as the men arrived the French Merchant Marine went on strike, leaving them stuck for two weeks. Finally, the men boarded a ship and headed home. As they sailed through the Mediterranean and into the Atlantic, they were treated to a wonderous sight. “We could look up and see the Rock of Gibraltar,” Freeman recalled. After an uneventful trip, the ship arrived in Boston, Massachusetts. Freeman did not bother to call his parents and instead boarded a train for home. There was a simple reason: “I didn’t even know they had a telephone.”

After a few days, the train arrived at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. His oldest brother, Earl (Freeman had four older brothers), greeted him. “He carried me from the train and brought me home,” he said. They stopped off in Meridian, where Earl called home to tell their parents of Freeman’s imminent arrival. They had a phone after all.

The two brothers reached home, and as they climbed the hill in front of their house, Freeman’s father walked onto the front porch. “He shook hands with me and didn’t say nothing,” he recalled. “He just opened the door and said, ‘Go on in.’” Freeman’s mother was waiting for him but could not hug her son. His brother Carry had returned a day earlier from the Pacific and hugged his mother so tightly she broke a rib. “That was hard to swallow,” Freeman said. “She was rubbing my knees and seeing about me.” The date was December 2, 1945. Brad Freeman was home.

On Freeman’s second Sunday home, he saw Willie Gurley and reminded her that they used to play together as children. They started dating and eventually married on June 29, 1947. They had two girls, Beverly Clark in 1948 and Rebecca Louis in 1953. After more than 60 years of marriage, Willie passed away on October 5, 2008.

Upon Freeman’s return from the war, he went to work driving a truck for most of 1946, then went back to college on the G.I. Bill but found himself bored. He held a number of jobs, including working as a mailman from 1954 until 1986 and drilling for oil on his grandmother’s property. “I get a little check every year,” he said about his oil revenues.

But his favorite job was farming. “I always liked it.” Freeman tended cows and grew peaches, pears, and hay. When he wasn’t farming, he hunted and fished and enjoyed just sitting on his front porch. As of 2019, at the age of 95, Freeman continues to run his farm (he ran a little late for this interview because he had to park his tractor in the barn).

In 1989, Dick Winters wrote Freeman about the upcoming bookBand of Brothersby historian Stephen Ambrose, which chronicled Easy Company’s wartime exploits. “Although your name is not mentioned under the index you have the satisfaction of knowing you were their! [sic]” wrote Winters. “You got the job done.” Winters then addressed Freeman’s role in Operation Pegasus, the river-crossing rescue of British paratroopers in the Netherlands. “You know many of the details about the rescue that your leaders and his never knew. Further more [sic] you never forgot one detail.” Winters concluded with the two-word saying that became his maxim: “Hang Tough!”

Winters thought highly of Freeman. In 1990, Winters wrote fellow Screaming Eagle veteran George Koskimaki, who was finishing a book about the 101st in the Battle of the Bulge, titled Bastogne. Winters told Koskimaki, “Men like Brad never seem to get promotions or decorations for valor, but when the going gets tough, it’s men like Brad that are always there. They got the job done and won the battles.”

Freeman also thought highly of Winters, inviting him to his farm and explaining that he went to church every Sunday to give thanks for “the way my God and you looked after me,” adding, “I never did give up.”

Freeman found that Ambrose’s Band of Brothersgave him a better appreciation of Easy Company’s exploits. “I didn’t know what was going on,” he said of the war. “I just knew what I was in on.” He felt the same way about the HBO miniseries of the same name that premiered in 2001.

After the miniseries, actor/producer Tom Hanks, at Dick Winters’ request, personally invited Freeman to the 2009 Easy Company reunion in Erie, Pennsylvania. Freeman attended and reunited with Ed Joint, whom he had not seen since they were wounded together in 1945.

Today, Freeman takes pride in his association with the 101st Airborne Division and Easy Company. His home is a memorial to his service. Pictures, plaques, and paintings representing World War II airborne combat cover his walls. A large 101st Airborne crest stands outside his front door. Gifts arrive almost weekly from people all over the world wanting to connect with a living embodiment of Easy Company or to just thank him for his service. His friends and acquaintances call Freeman “Mr. B” out of respect.

He speaks to school classes and civic groups, explaining his role in World War II and the airborne infantry. He also attends World War II-related conventions, again sharing his story, signing memorabilia, and chatting with other veterans. He has participated in other events, like dropping the puck at a hockey game.

Despite his advanced age, Freeman still enjoys traveling to Europe and revisiting his old battlefields. His knee and leg injuries still bother him, as does his back from the rough ride into Bastogne. He appreciates the way Europeans live their lives. “They should send [American] people here to show them how clean the sides of the streets are.”

Since Band of Brothers, Freeman has stood as an inspiration to today’s Screaming Eagles. In 2017, he attended the 101st Airborne Division’s annual “Day of the Eagles” at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he inspected the entire division with Maj. Gen. Andrew W. Pappas, the division commander. Freeman told the general that he must feed his soldiers “better then they fed us, ‘cause they was big boys.”

He later spent a day with today’s Easy Company, 2-506 Infantry, under the command of Captain Zac Shutte. Freeman visited again with Easy’s mortarmen, explaining to them the differences between World War II’s and today’s mortar tubes. He has also attended a change of command ceremony when Shutte transferred from Easy Company to India Company and handed Easy over to Captain Charles Bird.

When elements of Easy Company traveled to Toccoa, Georgia, where the company was born, Captain Shutte and First Sergeant Randy Shorter invited Freeman to come. Freeman slept on a cot at the local armory with the young soldiers and joined them for a run up Currahee Mountain, although Freeman rode in a vehicle. As the soldiers played tag and ran backward up the mountain, one of Freeman’s friends asked him if those soldiers could have run with him back during his training. Freeman simply responded, “Oh yeah.”

Today, Freeman looks back fondly on his experiences in World War II. “I volunteered for it, and I expected to do whatever it took,” he said. “I’m glad that I made it.”

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for Arlington National Cemetery and the author of Patton’s Photographs: War As He Saw It. He is also a historian/tour guide for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours where he leads tours of General George S. Patton’s European battlefields, including locations where Easy Company fought.