By William E. Welsh

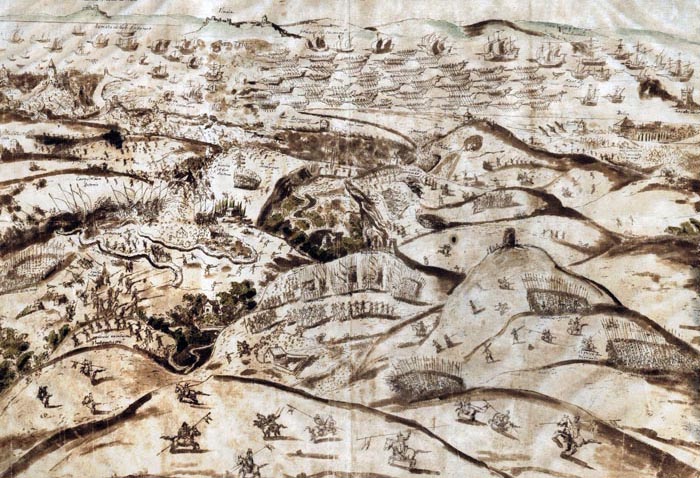

On June 27, 1570, an Ottoman fleet sailed against Venetian-held Cyprus during the reign of Sultan Selim II. After a short siege of Nicosia, the Turks then besieged Famagusta. Its Venetian defenders fought tenaciously but succumbed to the Ottomans on August 5, 1571, after a grueling 11-month siege.

Ottoman general Mustafa Pasha initially offered to allow the Christian troops to sail to Crete. But his mood turned sour and he reneged on his offer. The bloodthirsty Turks slaughtered the Christians. In an act of unspeakable cruelty, Venetian commander Marco Antonio Bragadin was tortured and flayed alive.

The Venetians vowed revenge. Other Catholic maritime powers in the Mediterranean region sympathized with their situation. At the urging of Pope Pius V, Spain, Genoa, Venice, the Papacy, and the Knights of St. John formed a powerful Holy League. It was the only way the Christians could meet the Ottomans on equal terms at sea. The Venetian Arsenal, a massive complex of shipyards and armories, churned out war galleys and galleasses for the expedition.

On October 7, 1571, the opposing fleets faced off at the Battle of Lepanto in the Gulf of Patras. The league’s left division was led by Venetian Admiral Agostino Barbarigo, the center division by fleet commander Don John of Austria, and the right division by Genoan Admiral Gianandrea Doria. The commander of the rear division was Alvaro de Bazan, Marquis of Santa Cruz, who was one of the greatest naval commanders in Spanish history. Aboard his flagship Lupa (Wolf), Santa Cruz performed his duty magnificently. At a crucial point in the battle, he sent a portion of his command to plug a dangerous gap in the Christian line.

One of the soldiers who fought at Lepanto was Miguel de Cervantes, who would go on to write the novel Don Quixote in 1605. In Don Quixote, he spoke in glowing terms of Santa Cruz. The Spanish admiral was “that thunderbolt of War, the father of his soldiers, that fortunate and invincible captain.”

Alvaro was born in Granada on December 12, 1526, to a respected and highly accomplished family from the lush Baztan valley of Navarre. At birth he was given his father and grandfather’s name. The valley in which he grew up lies north of Pamplona and is nestled along the province’s northern border with Aquitaine. His family was one of the principal houses of Navarre, and it had rendered loyal service to the kings of Spain. The family modified its surname, in an effort to reflect the valley from which it came, from Baztan to Bazan. Because of their affluence, his parents were able to send young Alvaro to school in Gibraltar. But he soon went to sea to learn the naval profession.

Alvaro’s grandfather had fought in the decade-long Grenada War that ended in victory for Castile-Aragon in 1492. Alvaro’s father, Don Alvaro de Bazan, Marquis of Viso, served King Charles V, who ruled both the Spanish Empire and the Holy Roman Empire, as Captain General of the Ocean Sea. Spanish shipbuilding was performed largely by private contractors, and Viso also designed and built ships for the Spanish crown.

The Bazan family acquired extensive lands in La Mancha both as compensation for service to the Spanish crown and also from outright purchase from the king. The Marquis of Viso took advantage of the arrangement to purchase the town of Santa Cruz de Mudela from Charles V. When young Alvaro came into his own later in his career and climbed the ladder of success as a preeminent Spanish naval commander, the inspiration for his title came from Santa Cruz de Mudela, for he wished to be known as the Marquis of Santa Cruz.

Because of his lineage, 17-year-old Alvaro received command in 1543 of a Spanish naval squadron composed of four ships and 1,200 sailors stationed in the Atlantic Ocean. The squadron patrolled the waters from Gibraltar to the Bay of Biscay. Bazan the Younger won his first laurels in a major naval clash that unfolded during the Italian War of 1542 to 1546, one of the many wars that pitted Charles V against French King Francis I.

In the summer of 1543 a French fleet composed of 25 warships led by Jean de Clamorgan set out from Bayonne to attack Spain by raiding along its coastline. The Marquis of Viso found the French anchored at Muros Bay in Galicia on July 25. Although the Spanish had only 16 warships, they were on average larger than those of the French. Having captured the French at anchor, the Marquis of Viso sailed directly for Clamorgan’s flagship and sank it. The French capitulated and the Spanish captured all but one of their ships, as well as 3,000 sailors. Bazan the Younger, whose squadron participated in the battle, also basked in its success.

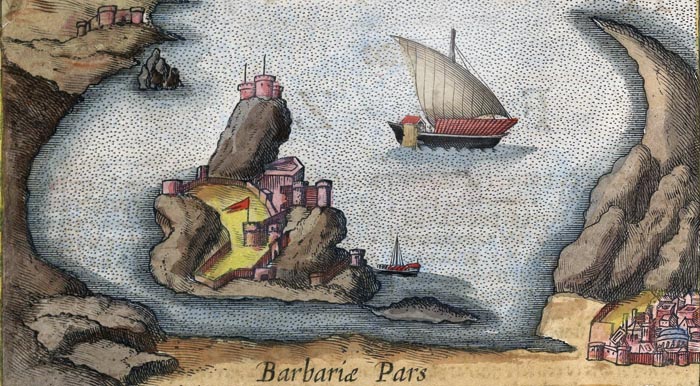

Much of the younger Bazan’s career over the course of the next two decades was devoted to checking the expansion of Ottoman corsairs based in North Africa. The Ottomans referred to the 1,200-mile coastline from modern Morrocco to Libya as the Maghreb, whereas the Spanish called it the Barbary Coast. Shortly after the turn of the century corsairs from the eastern Mediterranean relocated to the Maghreb in search of greater riches by raiding Spain, Italy, and nearby islands. This ultimately sparked a long-running amphibious war along the Barbary Coast between the Spanish and the Muslim corsairs. Bazan the Younger played a key role in protecting Spanish lands in the western Mediterranean from corsair raids.

After the fall of Granada in 1492, the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella embarked on a program to construct presidios at key points along the Barbary Coast. The presidios would serve as bases from which to disrupt corsair activity. Archbishop Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros of Toledo, who had his hand in military as well as ecclesiastical matters, drew up a plan for constructing the strongholds.

Cisneros tapped Pedro Navarro, a brilliant military engineer who had served with distinction in Italy during the Italian Wars, to conduct an offensive against the corsairs and build presidios in the ports and cities he conquered. In 1510 Navarro led Spanish forces that captured Algiers, Bougie, Tlemcen, Tripoli, and Tunis. Navarro generally chose a rocky crag or strategically located island to command the harbor traffic. The Spanish referred to these rock-fortresses as peñons.

Navarro’s short-lived offensive was not sustained by his successors. As time went by, the presidios became wholly defensive in nature. The isolated garrisons had to wait anxiously for resupply from Spanish war galleys because the local Arabs and Berbers would not sell them supplies.

Sixteenth-century clashes in the Mediterranean Sea typically involved war galleys and smaller vessels, such as galiots and fustas that combined oars and lateen sails. Because of their sleek design, war galleys could not hold much cargo. They had to put into port frequently to take on food and water. The longest they might go at sea was two weeks.

These vessels routinely participated in amphibious operations, patrols, and raids. Galleys were well suited to capture coastal objectives. An attacking naval force might land troops and guns to assault the objective from land while their galleys furnished fire support with their bow guns.

Fleet-versus-fleet engagements were unusual. This is because the great admirals knew that attempting to destroy an enemy’s fleet was a major gamble and generally not worth the risk. The path to victory in galley warfare was not to destroy the enemy’s fleet, but rather to capture his bases in order to deny him control of the coastline and its ports, harbors, and coastal fortifications. On the rare occasions that galley fleets fought against each other, such as at Preveza in 1538 and Lepanto in 1571, they also might incorporate sail-driven ships, such as the galleon, caravel, or cog.

The Spanish needed ships with the endurance of merchant vessels that could carry guns and soldiers to fend off attacks. They also needed ships that could withstand the rough weather encountered in trans-Atlantic voyages. As early as the 1530s, the Spanish had begun building carracks and galleons capable of transporting men, equipment, and treasure across the Atlantic. The Marquis of Viso and his son both made major contributions to the design of the Spanish galleon, which was an iconic vessel of the Spanish empire. When his father passed away in 1559, the Bazan the Younger built on the advances his father had made to perfect the design of ocean-going galleons used in trans-Atlantic voyages.

His innovative design incorporated the best features of the Portuguese caravel. He designed a standard galleon that was 100 feet long and 30 feet wide and could transport 600 tons. Such capacity was necessary both for storing supplies for the crew on long voyages and for transporting goods and treasure from Spanish possessions in the Americas back to Spain. That was just one of many sizes, though. Depending on the specific model, it might have three or four masts, a combination of square and lateen sails, and several decks. For armament galleons had from 24 to 48 guns. A typical crew size was 200 sailors and 100 soldiers.

A Spanish galleon’s guns were not sophisticated enough at that stage of artillery evolution to fire repeated broadsides at enemy vessels. They were so heavy that once fired, the crews could not easily run them back and fire again. Besides, the Spanish were not keen on destroying enemy ships because they preferred to capture them as prizes and reflag them. A Spanish galleon usually fired one broadside before coming alongside the enemy ship for boarding. It then sent sailors and soldiers to fight their way aboard the enemy ship with half pikes and swords.

For his design achievements, King Philip II bestowed on Bazan the title of Marquis of Santa Cruz in 1559 and gave him the governorship of Gibraltar. The following year Santa Cruz was promoted to Captain General of the Galleys. He transferred his squadron to the western Mediterranean to address the continuing threat posed by the Ottoman fleet against Spanish possessions in Italy and the Muslim corsairs in the Maghreb.

One of his first expeditions was to drive the corsairs from Peñon de Velez de Gomera on the coast of modern-day Morocco. For the next several years he worked to drive the corsairs from their many makeshift bases in the region. This was necessary because the Ottoman corsairs routinely raided the eastern coast of Spain where they would assist the Moriscos. The Moriscos were Moors in Spain who had been coerced into becoming Christians.

During the winter of 1564-1565, Santa Cruz led a Spanish force in a surprise attack against Ottoman corsairs based at the mouth of the Tetuan River east of Peñon de Velez de Gomera. He departed Seville with six galleys and stopped at Gibraltar and other Spanish-held ports in the vicinity to gather additional ships. With his galleys as the core of the fleet, he added six brigantines, four caravels, three armed chalupas (fishing boats), and a galiot. The two-masted brigantines were used not only to transport troops, but to conduct swift reconnaissance against targets. His small fleet had a total of 225 arquebusiers and crossbowmen for amphibious assaults.

In mid-February 1565, the fleet sailed east from Gibraltar. The chalupas with their shallow draft carried the soldiers to an anchorage near the mouth of the Tetuan where the men attempted to burn two Ottoman raiding vessels. They were counterattacked by a strong force of arquebusiers and light cavalry. The chalupa crews fired swivel guns to assist the Spanish troops. A fierce melee ensued. The Ottomans got the upper hand in the frenzied fighting. Fearing that his soldiers would be annihilated or captured, Bazan ordered the galleys to move to their assistance. The bow guns of the galleys sent shells crashing into the Ottoman ranks. This furnished the cover Santa Cruz needed to withdraw his troops. His fleet suffered 50 killed in the unsuccessful attack.

In September 1565 Santa Cruz assisted Don Garcia de Toledo Osorio, Viceroy of Sicily, with the transport of 9,600 Spanish reinforcements to Malta to assist the Knights of St. John who were besieged in the Grand Harbor by 40,000 Turks. Santa Cruz commanded three of the eight Spanish galleys. Other galleys came from Genoa, Florence, and the Knights of St. John’s own fleet. The fleet arrived in Mellieha Bay on September 6 and disembarked the troops the following morning. Three years later, Santa Cruz was given command of Spain’s Neapolitan fleet.

The effort to relieve the Venetians at Cyprus five years later, which failed because the Catholic maritime powers did not act with enough urgency, ran concurrent with Pope Pius VI’s effort to form a Holy League composed of Latin kingdoms and republics to contest Ottoman sea power.

During the Christian naval offensive that culminated in the Battle of Lepanto on October 7, 1571, Santa Cruz served as one of the key advisers to fleet commander Don John of Austria. As such, he helped Don John decide the arrangement of forces for battle. Of the four available commands, Santa Cruz chose to lead the rear guard of 38 galleys. His duty as commander of the rear guard was to reinforce the three front divisions as he saw fit or to contain breaches of the main line.

Philip instructed Don John to heed the advice of his principal fleet commanders, namely Doria and Santa Cruz. Doria was by nature cautious, whereas Santa Cruz was daring and courageous. While Doria cautioned Don John that it was too late in the year for a naval campaign of such magnitude, Santa Cruz advised the commander in chief to proceed with the campaign regardless of the weather. Don John’s spirit was more like that of Santa Cruz, and he took Santa Cruz’s advice over that of Doria.

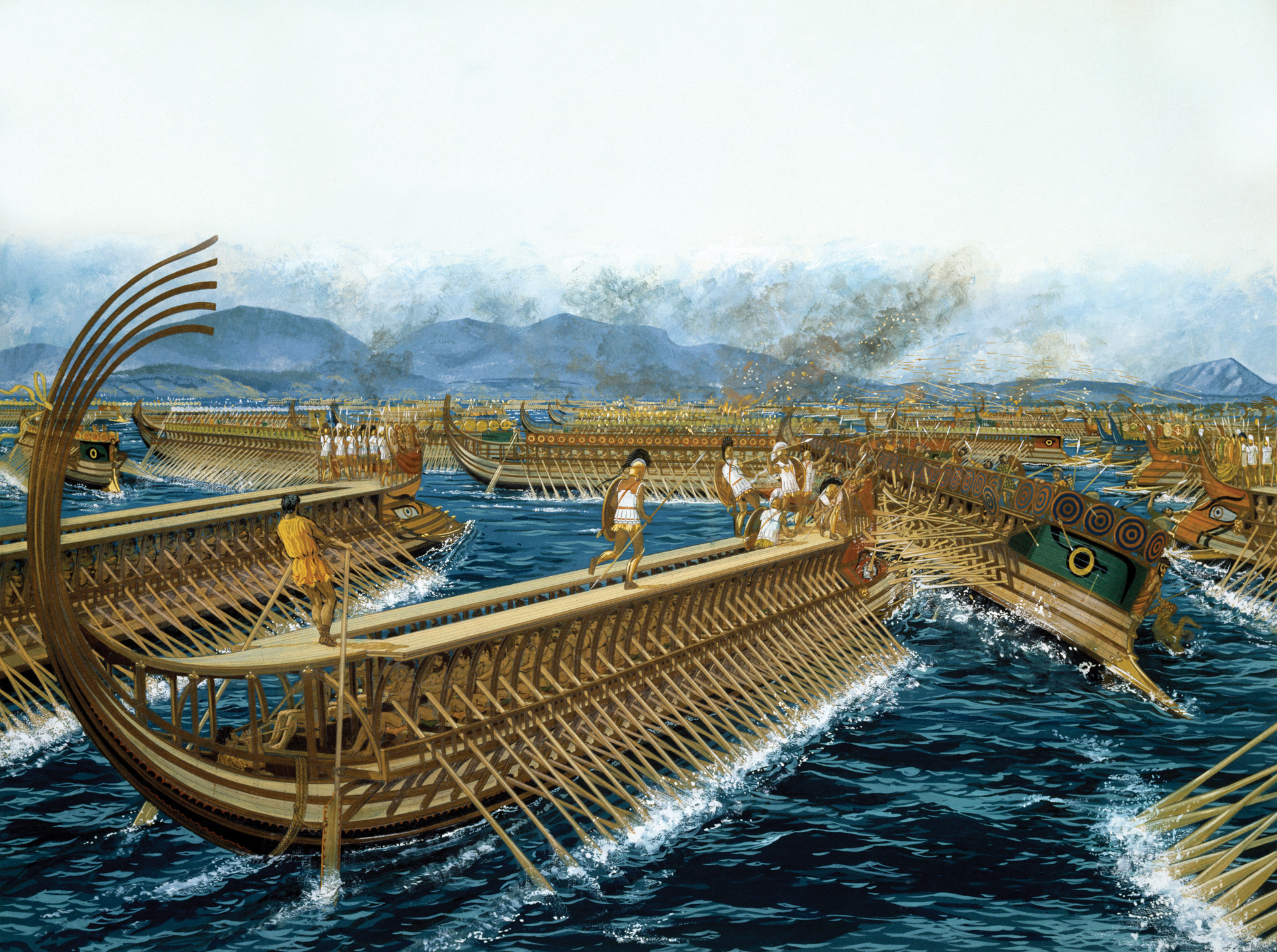

At mid-morning on the day of battle the Holy League’s fleet assembled in the Gulf of Patras. The galley captains could not have asked for better weather. The wind was light, the sea calm, and the sky clear.

The Christian fleet’s secret weapon was its six Venetian galleasses. Each of these specially designed vessels bristled with 40 guns on two decks. The galleasses not only mounted guns fore and aft, but also had a few guns squeezed in among the rowing benches in order to fire broadsides.

The job of the galleasses was to inflict heavy damage on the Ottoman galleys before the fleets collided in battle. Both fleets began moving slowly toward each other an hour later. At 11 am the galleasses, which were three-quarters of a mile in front of the Christian main line, began shelling the enemy with thunderous fire from a distance of 1,200 yards.

As the Turkish galleys approached the Christian line, the galleasses on the Christian left and center wreaked terrible havoc on them. Spanish shells smashed banks of oars and sent showers of deadly splinters raining down on the Turks. The galleasses wheeled as the Turkish galleys passed, firing first into their sides and then into their sterns as they made for the Christian galleys. When the galleys clashed, Spanish arquebus fire swept their forward platforms. Not all of the Turkish soldiers had arquebuses. Many fought with only bows, and their arrows glanced harmlessly off the armor of the Spanish knights. When galleys collided, Spanish troops swarmed onto the Turkish galleys and fought desperately to secure them as prizes.

Neither Ali Pasha, commanding the Ottoman center, nor Mehmet Sulik Pasha, leading the Ottoman right, showed any of the requisite skills of a good admiral. The only Turkish commander who exhibited any measure of tactical competence was Uluj Ali Pasha, who commanded the Ottoman left opposite Doria. Uluj, who had more galleys than Doria, stretched his line until Doria was forced to shift his line to the right to avoid having his flank turned. This opened up a wide gap between the Christian center and right that some of Uluj’s galleys exploited. Although Santa Cruz had reinforced Don John’s division in the center with some of his galleys, he had retained enough to thwart the Ottoman thrust through the gap. Uluj suddenly found fresh Christian galleys bearing down on him to his front, while galleys of both the Christian center and right had turned to take his breaching galleys in the flank. Uluj decided to quit the fight with 13 of his galleys that were undamaged.

The four-hour Battle of Lepanto was Santa Cruz’s finest hour up to that point in his career. By containing Uluj’s penetration of the gap that opened up late in the battle, he saved the Christian fleet. The Christians lost 15,000 men, and the Ottomans lost 30,000. The Christians lost only 12 galleys, whereas the Turks lost 113 galleys sunk and 117 captured.

The Fourth Ottoman-Venetian War ended with the Venetians pulling out of the Holy League and making a separate peace with the Ottomans on March 7, 1573. The Venetians did this because they desperately needed to maintain their lucrative maritime trade with the Ottoman Empire.

In the wake of Lepanto, Spain’s priority shifted from the Mediterranean to the Spanish Netherlands where the Spanish were heavily engaged trying to suppress the Dutch Revolt. Philip entered into a truce in 1578 with the Ottoman Sultan Murad III that allowed the Spanish monarch to focus his military assets against the Dutch and protect his colonies in the Americas. The result in the Mediterranean was that the Ottomans were able to reinforce their garrisons throughout the Maghreb, as well as foment an Arab rebellion against Portuguese rule in Morocco.

The Ottomans subsequently furnished funds to the Saadi Dynasty in Morocco to assist them in expelling the Portuguese. Unwilling to give up his North African possessions, 24-year-old King Sebastian of Portugal led an army against the Saadis. In an effort to crush the Arab rebellion in Morocco, Sebastian launched what amounted to a small crusade in Morocco. The crusade floundered, and he was slain in the Battle of Alcacer Quibir fought on August 4, 1578.

Sebastian’s death had far-reaching consequences for both Spain and Portugal. He had no heirs, and therefore his uncle, Cardinal Henry, succeeded him. But he also died childless on January 31, 1580. This plunged Portugal into a succession crisis. King Philip of Spain had a strong claim to the throne through his mother, who was a Portuguese princess, and he exercised it. But it was contested by another claimant. This individual was Dom Antonio, Prior of Crato, who was the son of Duke Louis of Beja. On July 24, 1580, Dom Antonio had the audacity to crown himself King of Portugal. Philip resolved to unseat him by force.

Philip put Santa Cruz in charge of Spain’s Atlantic fleet for the invasion. The fleet comprised 80 galleys and 30 galleons. The Spanish admiral outfitted the fleet at Cadiz. Santa Cruz would sail to Setubal, 30 miles south of Lisbon, where he would rendezvous with a 40,000-strong army led by the veteran general Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba. He would then transport Alba’s army to a position behind Antonio’s army covering Lisbon.

Alba’s army departed Badajoz on June 27, 1580, on its march to Setubal. Once the army arrived at Setubal, Santa Cruz transported them to the Tagus River. Since the Portuguese nobility and clergy pledged their fealty to King Philip, Dom Antonio had been forced to cobble together a militia army composed of peasants, townspeople, and African slaves to whom he promised freedom if the army was victorious. On August 25 Alba’s veterans soundly defeated Antonio’s inexperienced soldiers at the Battle of Alcantara. The following summer Philip was crowned in Lisbon with the approval of the Portuguese nobility. Through conquest of Portugal, Philip inherited a large navy and a maritime empire that spanned the globe.

Following his defeat at Alcantara, Antonio had fled to England to request military assistance. In the meantime, he received word from local officials in the Azores that they supported his claim to the Portuguese throne. This gave Antonio a base from which to continue his struggle against Philip. The Azores, which were situated 950 miles southwest of Lisbon, were a crucial way station for the Spanish treasure fleets returning from the Americas.

Antonio communicated his desire for assistance through the proper channels to both Queen Elizabeth of England and King Henry III of France. Both England and France were rivals of Spain, and neither wanted to see King Philip increase his power. In return for support, Antonio promised that if the Azores were secured for him he would give access to the Portuguese resources in the Atlantic to his benefactor. This appealed to Spain’s rivals, for whoever controlled the Azores would have an excellent way station for sailing ships setting out from Europe for the other continents.

Elizabeth allowed English privateers to assist. Antonio received support in France from dowager Queen Catherine de Medici. She told Antonio that she bankroll a fleet of French privateers to assist him. She even arranged for fellow Florentine Filippo di Piero Strozzi to command the fleet.

In the summer of 1582 Strozzi put to sea at the head of a French fleet composed of 60 warships and transports with 7,000 soldiers aboard. His objective was to secure the Azores for Antonio. The fleet included a squadron of nine English privateer ships led by Captain Henry Richards.

Meanwhile, Captain Pedro de Silva led the Spanish-Portuguese naval vanguard, which was composed of two galleons, three caravels, and five other vessels, to the Azores. He had instructions to wait for the arrival of Santa Cruz with the main fleet before undertaking any action against the enemy. But De Silva decided to land some of his soldiers on Sao Miguel on July 15. At the time, Antonio was on the island of Terceira with some Portuguese troops loyal to him. He quickly ferried his troops to Sao Miguel to contest the Spanish occupation but re-embarked them when he learned that Santa Cruz was approaching the island with a large fleet.

Santa Cruz soon arrived with a fleet of 31 ships that included two massive Portuguese galleons, armed merchantmen, and transports carrying 4,500 soldiers. The two Portuguese galleons were the admiral’s flagship, the 48-gun San Martin, and the 34-gun San Mateo. The Spanish admiral weighed anchor at Vila Franca do Campo on the south side of Sao Miguel but found the local people hostile.

The two fleets clashed 18 miles south of Sao Miguel on July 26, 1582. The encounter occurred beyond sight of land, which was rare for naval battles in that period. The two fleets sailed on a northerly course three miles apart from each other. The French initially had the weather gauge and attacked the rear of the Spanish fleet commanded by Santa Cruz. At midday, Strozzi bore down on the San Mateo, passing just windward of the Spanish line. The San Mateo, which was sailing leeward, withheld fire from her double decks until the spars of the two vessels brushed each other. Strozzi’s flagship and four other vessels in his fleet isolated the San Mateo. After pounding her with broadsides, the French successfully boarded and captured the large ship.

Meanwhile, Santa Cruz maneuvered the San Martin toward Strozzi’s flagship. Once within range he pummeled his opponent’s flagship with a broadside. His men then swung over to the French ship and fought furiously with Strozzi’s crew for control of it. The Spanish prevailed in the melee, and afterward the decks were awash with the blood of 400 dead Frenchmen. Strozzi, who was mortally wounded, was carried to Santa Cruz. The French admiral surrendered his vessel and then succumbed to his wounds.

Although the San Mateo was crippled from extensive shot damage to her side, Santa Cruz was able to have it towed to port at Villa Franco de Campo on the south side of San Miguel Island. The French lost 10 ships and 2,000 men in the clash at sea, whereas the Spanish suffered 200 killed and 500 wounded.

Santa Cruz’s ships prevailed in the fighting in large part due to his excellent leadership, yet he inadvertently marred his glorious victory by ordering the execution of the French prisoners captured in the battle. He did this despite the loud objections of his own men. The Spanish put 380 French sailors and soldiers to death.

The Spanish admiral decided to wait until the following year to carry out the landing and conquest of Terceira Island with his galleys and landing barges. He left a garrison of 2,000 Spanish soldiers on Sao Miguel to await the fleet’s return the following year.

Santa Cruz returned with his Atlantic fleet to the Azores chain in the summer of 1583 to complete the Spanish conquest. The fleet comprised five large galleons, 31 armed merchantmen, 12 galleys, two galleasses, and 48 smaller vessels. Aboard the fleet were 9,000 soldiers and 6,000 sailors and oarsmen.

Santa Cruz would have to pry 8,000 French and Portuguese troops from Terceira. While his supporters risked their lives for him, Dom Antonio was in France attempting to raise more troops. Santa Cruz, who led the galleons to the Azores, rendezvoused at Sao Miguel with Admiral Diego de Madrano, who commanded the galleys. The galleys would furnish the close-range fire support with their bow guns for the oar-driven barges that would land the troops on the island. The Spanish fleet arrived without incident off Terceira on July 23.

French Admiral Aymar de Chaste commanded the 3,000 French troops, and Governor Manuel de Silva led the 5,000 Portuguese troops on the island. De Silva had gone to great lengths to improve the coastal defenses, and they were well manned against an assault.

De Silva had detailed four companies of infantry to defend the works. The coastal works consisted of 31 small stone forts and 300 guns. These forts and coastal batteries were connected by a series of protected trenches. He deployed the rest of the troops to defend the towns of Angra on the south side and Praia on the east side. His ships were anchored in the harbor at Angra.

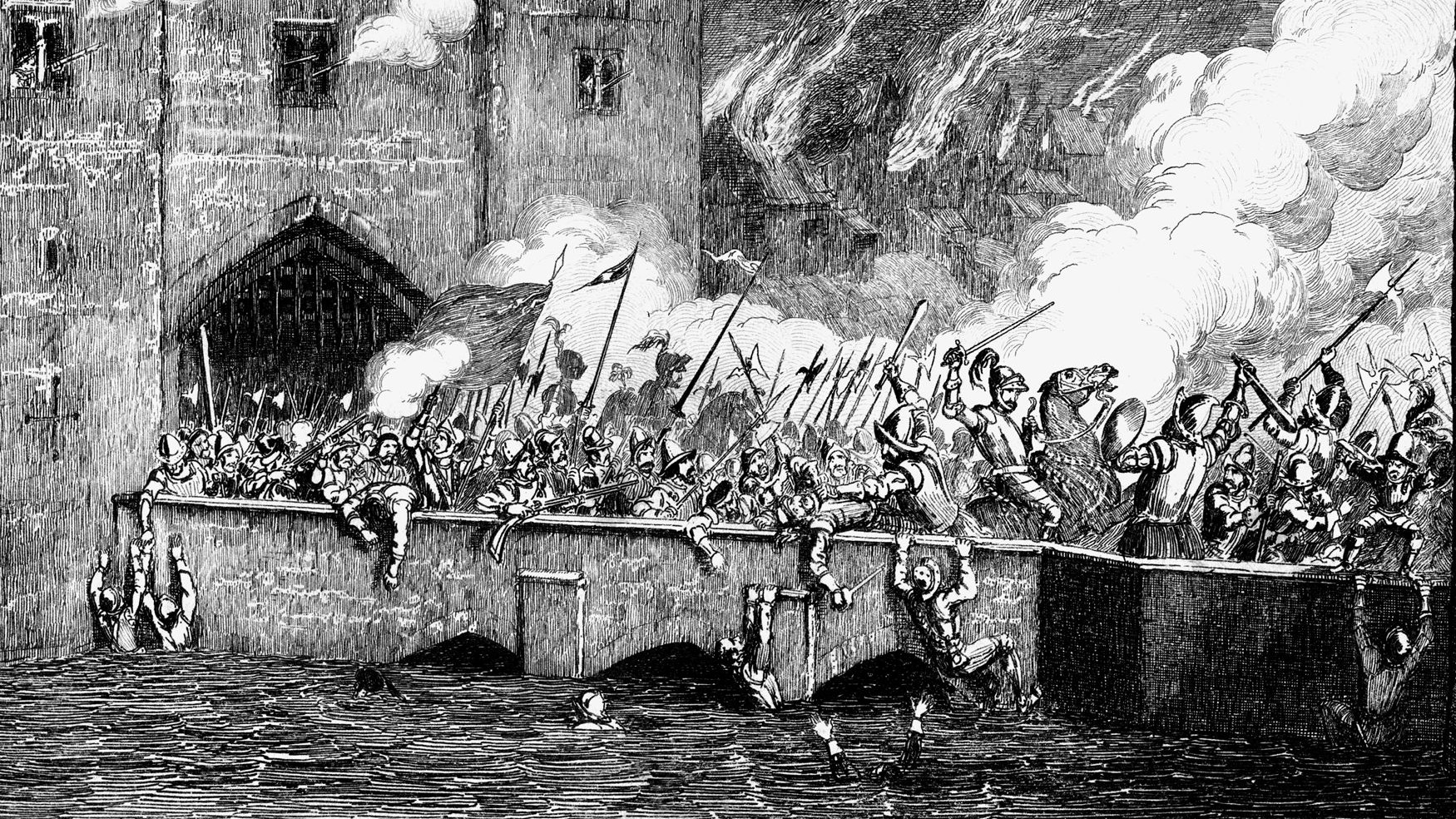

Under cover of darkness on the night of July 23-24, Santa Cruz transferred his men to the landing barges. The Spanish galleys towed the landing barges, which contained 4,000 soldiers, to shore under cover of darkness. The Spanish troops assaulted the shoreline at dawn. A withering fire from the coastal guns took its toll on the landing barges, but the assault proceeded unabated despite the losses. The Spanish galleys, which could turn with their oars to point their formidable bow guns at various targets, returned fire on the shore batteries, causing substantial damage.

Santa Cruz recounted the fiery coastal assault in his journal. “The flag galley began to batter and dismount the enemy artillery and the rest of the galleys did likewise,” wrote Santa Cruz. “The landing boats ran aground and placed the soldiers at the sides of the forts and along the trenches, although with much difficulty and working under the pressure of furious artillery, arquebus, and musket fire of the enemy. The soldiers mounting the trenches in several places came under heavy arquebus and musket fire but finally won the forts and trenches.”

Once the Spanish troops had a secure foothold, Santa Cruz came ashore to supervise the fighting. His presence electrified the troops, who after a fierce engagement forced the defenders to withdraw. After an hour of heavy fighting, the four companies of French and Portuguese who were entrusted with defense of the shore fled inland. When word reached De Chaste that the defenders of the cove had been routed, he promptly issued orders for the remainder of his troops to drive the Spanish into the sea. Rather than launch a counterattack, the Franco-Portuguese reserve simply took up a defensive position near the town of Sao Sebastiano at the southeast corner of the island in a blocking position protecting Praia, thereby allowing the Spanish to establish a firm foothold on the island.

Fighting raged in the settled parts of Terceira as the Spanish carried one enemy position after another. The following day, July 25, Santa Cruz landed the balance of his infantry. They proceeded to capture Angra and Praia. Santa Cruz allowed his men the customary three-day period to sack the towns. Afterward, they rounded up the surviving French and Portuguese troops who had hidden in the island’s forests. The fighting ended on August 2.

Rather than execute the French and risk a war with France, Santa Cruz decided to grant them safe passage home. But De Silva was executed, and the captured Portuguese loyalists were condemned to serve as galley slaves for the Spanish fleet.

In appreciation for his successful conquest of the rebellious Azores, Philip made Santa Cruz a Grandee of Spain, which raised him to the highest echelons of the nobility, and appointed him to serve as Captain General of the Ocean Sea, the same high office his father had once held. His primary responsibilities were defending Spain from attack by sea and ensuring the protection of the Spanish treasure fleets.

The renowned English privateer Sir Francis Drake would prove to be the bane of the Spanish navy for the rest of the decade. In a bold raid against Galicia in October 1585, Drake burned ships. He also put men ashore who desecrated Catholic churches. In response, Philip vowed to teach the English a lesson.

In August 1585 England signed a treaty with the Dutch in which it agreed to furnish the Dutch with 7,400 troops to fight the Spanish in Holland and Flanders. The event moved Spain closer to declaring war on England.

Meanwhile, Drake preyed heavily on Spanish outposts on both sides of the Atlantic. He attacked Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands in November 1585, sacked Santa Domingo in Hispaniola in January 1586, and plundered Cartagena in March 1586. At that point, King Philip instructed Santa Cruz to draw up plans for an invasion of England.

For the next three years, Santa Cruz devoted his energies to the invasion plan. He was an excellent choice for the assignment not only because of his experience commanding large fleets, but also because of his superb administrative skills. In July 1586 Santa Cruz submitted plans calling for a 500-ship armada, of which 150 would be large galleons and carracks, which would land 55,000 troops.

King Philip was adamant that the invasion should include the Army of Flanders led by Alexander Farnesse, Duke of Parma and governor of the Spanish Netherlands. The king approved Santa Cruz’s plans and sent them to Parma for his input. Parma formulated an alternate plan whereby he would be the primary commander and Santa Cruz would play a supporting role. The glory-seeking Parma believed that he could conquer the English with his Army of Flanders alone. He would build barges and ferry his army across the Strait of Dover to Kent. It was a fatuous idea given that Dutch and English ships prowled the English Channel and North Sea.

Parma suggested to the king that Santa Cruz’s armada make a diversion to draw the English away from his intended crossing. King Philip in turn suggested to Santa Cruz that he land his troops either in Ireland or at Plymouth as a distraction. Santa Cruz had an intense dislike of Parma’s plan. In the end, a compromise was worked out whereby the Spanish armada would keep the crossing area free of enemy ships so that Parma’s troops could make their crossing unhindered by Dutch or English vessels. The revised plan called for an armada of 130 large ships. Santa Cruz would transport 17,000 soldiers from Spain, while Parma would ferry 17,000 soldiers from his army across the English Channel in 120 barges.

In September 1587, Santa Cruz moved to Lisbon to supervise the assembly of the invasion fleet. His job was complicated by frequent interference by the king, corruption by private contractors, and disease that swept through the fleet while at anchor.

Drake continued to harass the Spanish navy. In a bold raid on Cadiz harbor on April 29, 1587, the English captain torched 27 Spanish ships. Although Santa Cruz sailed in pursuit of Drake, he was unable to catch him.

Santa Cruz would not live to see the armada sail, though, because he died on February 9, 1588. Philip ultimately spent 10 million gold ducats to finance the expedition. The king gave command of the fleet to the Marquis of Medina Sidonia, who was not a naval officer. The fleet set sail on May 28, but bad weather forced it into La Coruna. It departed that location on July 21 and when it arrived in the English Channel it found the English navy waiting for it. Major sea clashes occurred at Plymouth, Portland, and Gravelines.

Unable to ferry Parma because of the interference from the English navy, a decision was made to return to Spain by sailing around Scotland. The Spanish armada encountered some storms in the North Sea, but even worse weather lay ahead. The fleet, which was scattered over hundreds of miles, was pummeled for several weeks by storms off the coast of Ireland as it worked its way south through the Atlantic Ocean. The less seaworthy galleasses were not designed for such a long journey through storm-tossed waters. During that time numerous ships sank or ran aground on the rockbound coast of Ireland. On September 21 Medina Sedona arrived in Spain. Many ships were still at sea well into October. The Spanish ultimately lost 45 large ships in the ill-fated expedition.

If Santa Cruz had led the armada, it might have fared better. Leading oared and sail-powered ships in the Azores expedition had given him the experience to know what such a fleet could achieve and what was beyond its capabilities. Still, the expedition was fraught with problems from the moment it set sail. Spain’s greatest successful naval operation of the period remained the Azores expedition in which Santa Cruz had achieved victory both on land and at sea.