By Duane Schultz

The five Americans were trapped in a small, dark, empty wine cellar in an isolated French villa on the coast of Algiers. Upstairs, directly overhead, French police stomped back and forth across the rug that covered the trapdoor. The police were so close that the Americans could hear them questioning the owner of the house, Henri Tessier, and the senior American counselor to the Vichy French regime in Algiers, Robert Murphy, about their presence. It was Tuesday afternoon, October 23, 1942.

Tessier had instructed his Arab servants to stay away from the house for the rest of the day. That had made them suspicious enough, but when they spotted several sets of footprints crossing the sandy beach heading toward the house, they reported their suspicions to the police.

Murphy and Tessier pretended to be drunk. Murphy told the investigating officers that they had been having a party. There were women in the bedrooms upstairs, he whispered, and he pleaded with them not to embarrass a “senior American diplomat” who was only having a little fun.

The group in the cellar was led by Maj. Gen. Mark Clark. When he heard the voices, he kneeled at the bottom of the stairs, pointing his carbine toward the trapdoor. Years later he said that he was “prepared to shoot if necessary.”

A few hours earlier, in a meeting in the dining room upstairs with General Charles Mast, commander of the French XIX Corps in northern Algeria, Clark had persuaded Mast not to resist the planned American invasion of North Africa. Codenamed Operation Torch, it was scheduled to take place in three weeks. But if Clark and his group were captured by the French police they would be turned over to the Germans. “If we fell into Nazi hands,” Clark said, “it would be far from pleasant, and, of more importance, it would jeopardize the whole operation.”

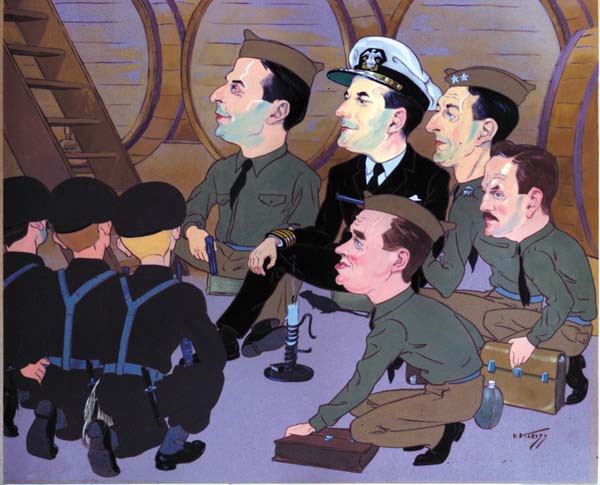

They had to get out of the house and back to the British submarine that was waiting for them offshore. With Clark were Brig. Gen. Lyman Lemnitzer, Colonel Archelaus L. Hamblen, Colonel Julius Holmes, and U.S. Navy Captain Jerauld Wright, an authority on naval gunnery, along with three British commandos. Five days earlier the group had left England for Gibraltar, where they were taken aboard HMS Seraph, an S-class submarine of the British Royal Navy; its commander, Lieutenant Norman Limbury Auchinleck Jewell, was known as Bill.

When Clark told Lieutenant Jewell they would be looking for a house with white walls and a red tile roof some 12 miles west of a fishing village called Cherchell, Bill said casually, “I am sure that we can get you in there and get you off again.” He had arranged for three commandos of the Royal Marines—Captain C.P. Courtney, Captain R.T. Livingstone, and Lieutenant J.P. Foote—to serve as bodyguards.

To enable the group to reach the shore and later return safely to the submarine, the commandos acquainted the Americans with their collapsible two-person kayaks. The boats were constructed of hickory wood frames covered with canvas. Because they could be folded to take up less space, they would be easy to hide onshore.

“I had never been aboard a submarine before,” Clark wrote, “and I soon realized that they were not made for a lanky six-foot-two man.” He had to crouch, and going to the latrine found himself nearly on all fours. When the Seraph submerged, the air grew so stale it made the men groggy. They passed the time playing bridge or trying to sleep.

They arrived at their destination at 4 am on October 21. Two Algerian fishing boats were anchored where they had expected to land. There was no choice but to spend the day submerged in deep water until 10 pm. The fishing boats were gone, but now there was no signal light from the villa indicating that it was safe to come ashore.

While they waited and watched for the light, someone suggested that they change into civilian clothes. “Hell no!” Clark said. “We’ll go ashore as American officers and nothing else. It will help the people we are dealing with to remember who we are and whom we represent.”

That settled, Clark strapped $2,000 in Canadian gold coins and American dollars into a money belt inside his pants for use in an emergency, and a little after midnight on October 22, when the signal light finally appeared from the house, the group made their way to shore through the heavy surf, emerging soaking wet. Robert Murphy was waiting for them on the beach.

“Welcome to North Africa,” he said.

Clark, who had prepared a formal statement that he had practiced in French, instead blurted out, “I’m damn glad we made it.”

The meeting with General Mast seemed to go well. Mast was eager to cooperate with the planned American invasion but insisted on knowing the strength of the landing force. He knew that if it was not sufficiently large, the Germans might be able to defeat it on their own. And if the Germans won, Mast would be in trouble for not having fought alongside them.

Clark knew this was a crucial point that could make or break the agreement with the Vichy government, so he greatly exaggerated the size of the American force. “I had to keep a poker face,” Clark recalled, “while saying that a half a million Allied troops would come in, and I said that we could put 2,000 planes in the air as well as plenty of U.S. Navy.” He knew that only 112,000 troops would be in the landing force. He later wrote in his diary that he had been “lying like hell.”

Clark’s ruse worked, and Mast agreed that the Vichy French troops under his command would not fight the Americans. After a lunch of chicken served with a hot peppery sauce, red wine, and oranges, Mast left while his aides worked out the details of the agreement.

Everyone seemed pleased with the outcome of the mission until an urgent telephone call that afternoon announced that French police were on their way to the villa. Clark and his party hustled into the wine cellar just as the police car pulled up outside.

While the police were still upstairs, Captain Courtney began to choke while trying to suppress a cough; they all knew the noise would give them away. Courtney whispered to Clark, “General, I’m afraid I’ll choke.” Clark hissed back, “I’m afraid you won’t.” Clark handed him a piece of chewing gum, which managed to stop the cough. Later, Courtney complained that American chewing gum was tasteless. Clark laughed and told Courtney that was because he had been chewing the gum himself for hours before he gave it to him! There is no record of Courtney’s reply.

The French police left after about half an hour, warning Murphy that they still had their suspicions and might be back to continue their search of the house. Murphy opened the door to the cellar and told Clark that they had better leave. He suggested that they hide in the woods until they could return to the submarine. Clark agreed; there was no reason to stay there any longer.

When they tried to get back to the submarine, the surf was so strong that Clark took off his trousers, concerned that the money belt containing the gold would weigh him down. But they could not get into the kayaks because of the high waves.

Finally, by 4 am on October 23, the sea had calmed down enough to try again to reach the submarine. But before they got into the kayaks again, what historian Jon Mikolashek described as “a bizarre exchange took place. Wet and [still] fearful that the gold would weigh him down, Clark rolled up his pants and ordered General Lemnitzer to drop his pants and give them to him. What followed next is a prime example of rank. Lemnitzer, now pantless, ordered a colonel to do the same. Eventually, the epic of the pants reached lowly Lieutenant Foote, who outranked no one and was forced to paddle to the submarine without any pants.”

The boats finally reached the submarine, but before they could be hauled on board one of them was tossed by the waves and slammed against the sub, cracking the wooden frame. The commando manning it leaped aboard, but the kayak drifted away and sank, carrying the coins, some secret papers, and Mark Clark’s pants. Clark radioed Robert Murphy and asked him to search for the lost articles in case they washed up on the beach. The pants were later retrieved, but not the papers or the gold. Murphy had the trousers cleaned and pressed, and he radioed Clark that they would be waiting for him upon his return.

The next day, October 24, the sub surfaced so that Clark could send a radio message to supreme commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower touting the success of his mission and describing how, with the arrival of the French police, they all had to hide in a wine cellar. To avoid any possible misunderstanding, however, Clark emphasized that they hid “in an empty—repeat empty—wine cellar.”

When they arrived back in London, Clark briefed Eisenhower on the mission. Clark was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, and he and Ike were invited to Buckingham Palace to meet King George VI. When introduced, the monarch said, “I know all about you. You’re the one who took that fabulous trip. Didn’t you get stranded on the beach without your pants?”

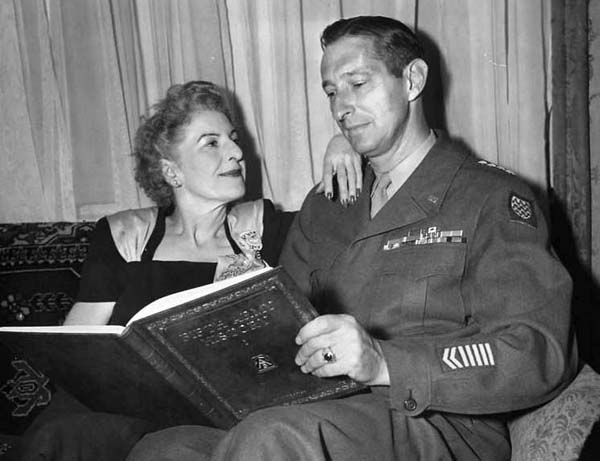

On the same day, General George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, called Clark’s wife, Maurine (called Renie), to assure her that her husband had returned from his mission. He warned her not to talk about it. “General Marshall made it very clear,” she wrote later, “that it was a secret that had to be kept. Adding that it had not yet been decided whether the story would be made public ever.”

Renie Clark had always been eager to promote her husband’s accomplishments. And, fortunately for her, three days after the Torch landings began on November 8, Marshall changed his mind about publicizing Clark’s secret mission.

Clark was promoted to lieutenant general on November 11, at that time the youngest three-star general in the U.S. Army. A War Department press release cited his diplomatic skill as well as his courage in undertaking the secret mission to Algiers. In response to a clamor from the press for more details, Marshall decided it would be good for public morale to release more stories of a personal nature to the public. And to start this new campaign he gave Clark permission to tell the press about his mission to Algiers, which included the story of his lost pants, which by then had been returned by Murphy, cleaned and pressed as promised.

The report of a general losing his pants on a cloak-and-dagger mission behind enemy lines immediately became headline news back in the United States. Mark Clark was suddenly a household name, a celebrity. The story captured the public imagination to such an extent that parents named their newborn sons after him, and thousands of people sent letters and gifts.

Clark’s biographer, Martin Blumenson, wrote, “Every war produced an act of personal daring, ingenuity, and devotion that gave individuals a permanent place in history: Nathan Hale had been the first such American. Clark was the latest.”

The celebrity Hollywood gossip columnist Louella Parsons called Clark ”America’s Dream Hero.” Time magazine noted that Clark was the “only U.S. general in World War II to lose his pants in enemy territory!”

Once the secret was out, Renie Clark did everything she could to enhance her husband’s newfound status. She went on war bond tours with Hollywood movie stars. “I talked five nights a week for nine months in 1943,” she wrote. “It was a roadshow, a new city each night, a one-hour talk in each city.” And she did the same in 1944. She was so effective that the War Department awarded her a Distinguished Service Citation for having sold more than $25 million worth of war bonds.

The prominent Redpath Speakers Bureau hired her to give public, paid lectures, which gave her an even larger audience. A compelling and magnetic speaker, Renie toured the country for Redpath, telling and retelling the tale of her husband’s dangerous secret mission, “one of the great adventures of all time.”

She talked relentlessly about his bravery and how he was winning the war. She read from his letters to adoring crowds and even displayed the famous trousers. And with that theatrical gesture she went too far; General Marshall did not like the idea of his officers being praised for losing their pants.

Marshall made his objections clear to Eisenhower, who in turn informed Clark that his reputation was being damaged by his wife and that he was becoming the butt of jokes. Clark was mortified. Even though he relished the attention and adulation, he was furious. “I do not want you to refer to me in any way in your talks,” he wrote to Renie. “Positively no quotes from me, for some I have seen lately have been embarrassing.”

But the damage had been done, and it fueled the already notable resentment among high-ranking officers that had started before the war when Clark was promoted from lieutenant colonel to brigadier general, skipping the rank of colonel. Less than a year later he was promoted to major general. Many officers senior in age and rank took offense.

Clark was also considered to be arrogant, vain, and overly ambitious for personal fame. Omar Bradley wrote some 40 years after the war that he thought Clark had been “too eager to impress, too hungry for the limelight, promotions and personal publicity.” Even George Patton, no stranger to arrogance and vanity, believed Clark “was more preoccupied with bettering his own future than winning the war.” Both Marshall and Eisenhower warned Clark on several occasions about being so overtly self-promoting.

It was hard not to notice that Clark insisted that the general’s star insignia painted on his jeep had to be bigger than what most other generals had and that he kept a public relations staff of almost 50. Their job was to make sure that photographers were available for important moments like a visit to the front lines. Photos were to be taken of Clark’s better side (the left) and news reports had to mention Clark’s name at least three times at the outset.

The episode with the pants brought Mark Clark to the attention of the American public, which needed heroes in 1942, and also perhaps a bit of comic relief after the defeats early in the war. The story was good for morale, and it undoubtedly helped Renie and other celebrities sell war bonds, which definitely helped the war effort.

Despite Clark’s admonitions to his wife, however, the story of the pants continued to reappear in the news until after the end of the war. An article in the New York Times on September 21, 1943, titled “Not Selling Clark ‘Pants,’” was based on an interview with Mrs. Clark. There had apparently been public pressure for her to hold an auction for the famous pants, the proceeds of which would go to the war effort. When a reporter asked if she would sell the item, she said she was “going to give them to the Smithsonian Institution” in Washington, D.C.

On January 9, 1944, another New York Times piece, this one called “Pants for Posterity,” noted that a spokesman for the Smithsonian said they had received many requests from visitors to see “the well-known britches [but] we have had no offers of the pants, and we, on our part, have made no steps to get them.” The writer, Jay Walz, added (perhaps in an off-the-cuff remark) that “the Smithsonian has no prejudice against pants,” and noted that the museum had collected some worn by George Washington.

Shortly after the war, on August 25, 1945, an article by Geoffrey Hellman and E.B. White in The New Yorker quoted another Smithsonian official: “[The pants] were offered, but were rejected as not being a complete exhibit.” End of story.

The notoriety acquired by losing his pants does not detract from Clark’s leadership in Operation Flagpole; it was a test of courage that he passed. On the day before he left England to fly to Gibraltar to board the submarine Seraph, Clark had written to Renie, “I am leaving in twenty minutes on a mission which is extremely hazardous. If I succeed and return, I will have done great things for my country and the Allied cause.”

He was not exaggerating about the danger or the importance. Later he admitted that he had “hardly ever been less certain of the success of an operational mission in my life.” More than 50 years after the war, historian Rick Atkinson described the mission as both “courageous and daft,” but added that it became “one of the most celebrated clandestine operations of the war.”

Duane Schultz, a psychologist, has written more than two dozen nonfiction and fiction books and numerous magazine articles on World War II. His more recent books include Crossing the Rapido: A Tragedy of World War II, Into the Fire: Ploesti, and Patton’s Last Gamble: The Disastrous Raid on POW Camp Hammelburg. He can be reached at www. duaneschultz.com.