By Tom Crowley

Special operations soldiers have existed since armed forces were first organized. Arguably, the hand-picked Greek warriors concealed inside the Trojan horse outside the gates of Troy 3,000 years ago were the first “special ops” troops.

During the French & Indian War in America, a unique band of frontiersmen, Rogers’ Rangers, gained fame for their code of conduct and special skills that made them a valuable instrument of mid-18th century warfare. The legacy of the Rangers endures today in both the U.S. Army’s Ranger Regiment and in the American special operations forces as they have developed over the past 60 years.

Undergoing jungle training near Deogarh, India, in November and December 1943, a band of nearly 3,000 American soldiers were gathered who would provide a unique World War II link between those early Rangers and the American special operations forces of today. This was the band of soldiers who volunteered for “Unit Galahad” in the China-Burma-India Theater and eventually became known as Merrill’s Marauders.

Modeled after the Chindits, the British long-range penetration group that operated behind Japanese lines in 1943, the American volunteers, who had come from commands in the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific, trained alongside the core group of Chindits being readied for their next long-range insertion.

In asking for volunteers for a “dangerous and hazardous mission,” the Army had made the promise that the extent of the mission would involve three months in combat and then the volunteers would be repatriated to the United States. This promise would be repeated often and finally become a source of contention for those who volunteered.

The unit consisted of three battalions that were further divided into six combat teams for tactical flexibility once in the jungle. The newly promoted Colonel Charles Hunter was their commander.

The 1st Battalion, under Lt. Col. William Osborne, was divided into the Red and White Combat Teams. The 2nd Battalion, under Lt. Col. George McGee, Jr., was divided into Blue and Green Teams, and Lt. Col. Charles Beach’s 3rd Battalion was divided into Orange and Khaki Teams.

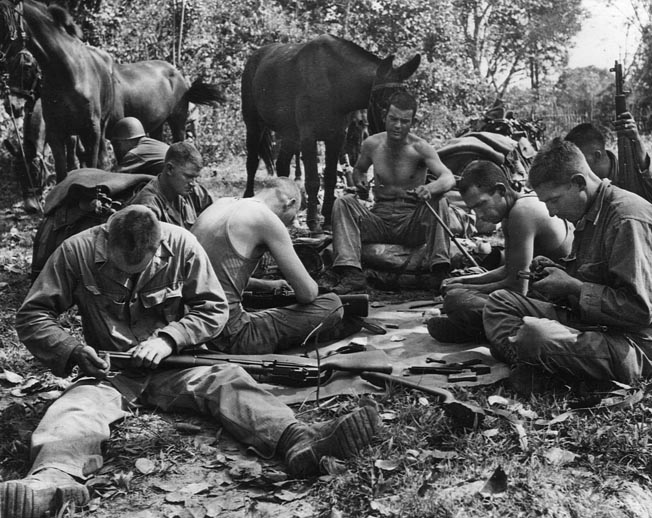

The unit received an important addition during the last weeks of 1943: 300 mules and 80 muleskinners from the 31st Quartermaster Pack Troop. Mules were absolutely necessary to carry the mortars and other heavy equipment needed to sustain combat capabilities once in the trackless jungle.

Although the initial plan was for the British Chindit leader, Brigadier Orde Wingate, to command the unit, the American leader in the China-Burma-India Theater, Lt. Gen. Joseph Stilwell, pushed for them to be assigned to his command; he prevailed. On January 1, 1944, the detachment was designated the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional). One of Stilwell’s long-time close aides, the bespectacled, pipe-smoking Brig. Gen. Frank Merrill, was appointed the new commanding officer with Colonel Hunter being “demoted” to serving as his deputy.

The men of the 5307th were both disappointed and puzzled. Colonel Hunter was liked and admired and had been the officer in charge of their unit from the very beginning. He had an excellent background both as a teacher of tactics and as a commander of infantry units prior to the war. Brig. Gen. Merrill, on the other hand, was an unknown quantity and primarily a staff officer filling the role of Stilwell’s G-3 (plans and operations) officer.

Unknown to the men, Merrill had two qualities that Stilwell prized: he had been one of Stilwell’s inner circle since 1942 and the long walk out of Burma, and he was a reliable yes-man. As senior generals often do, Stilwell had assembled family members on his staff, appointing his 32-year-old son Joe his G-2 and his son-in-law his adjutant.

Many of the men felt aggrieved by Merrill’s appointment, especially Colonel Hunter, a former West Point classmate of Merrill, who had understood that the unit was to be under his command. This widespread feeling of discontent would grow stronger over the coming months and continue well after the war was over.

American reporters following Stilwell visited Deogarh to establish what this new unit was all about. They were greeted by Merrill, who told them “his boys” were the best in the CBI Theater. The reporters, searching for a catchier name than the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) or Unit Galahad, decided the tag for the unit would be Merrill’s Marauders, the name under which it would become famous.

On January 27, the Marauders began their odyssey with a 1,200-mile train journey from the Deogarh camp to Margherita in Assam, arriving on February 6 near the Ledo Road jump-off point.

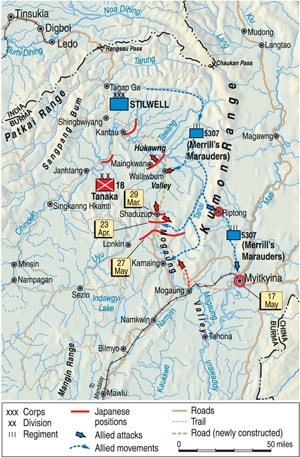

Instead of being lifted into Burma by air to strategic positions far behind the Allied lines, as the Chindits had planned, Merrill decided, with Stilwell concurring, that the Marauders would walk from India. This meant walking more than 100 miles along the Ledo Road and over the 3,727-foot-high Pangsau Pass through the Patkai Mountains to Stilwell’s headquarters at Shingbiyang at the head of the Hukawng Valley.

The reason given for Merrill’s decision to subject the Marauders to this marathon march, which eventually covered an estimated 140 miles, was to use it as a “shakedown” or a “toughening-up” exercise for the unit. It was not a popular decision with the Marauders. The dirt track was a clear trail forged by the Ledo Road construction crews, but it was subject to unseasonal rains.

They learned to march lightly packed in order to keep moving day after day and, as Merrill intended, a good deal of extra camp baggage, such as small cooking stoves, was abandoned along the way. In hindsight, this discipline really did prepare them well for their entry into the jungle proper.

The Marauders’ 1st Battalion set off on the march from Assam on February 7, with the other battalions following on consecutive days and marching at night to keep their movement secret. Two days later, when Tokyo Rose welcomed them to Burma on the radio, it was clear the secret was out, so they switched to day marches. On the 18th, the 1st Battalion reached Stilwell’s former headquarters at Shingbiyang.

Following the forward movement of the Chinese divisions, Stilwell had moved his HQ 25 miles farther along the Ledo Road to Ningbyen. Prior to marching any farther on the 19th, Merrill had his troops shave and put on their steel helmets so they would make a good impression when they encountered Stilwell.

Stilwell, however, was busy that day and it was not until the 21st at Ningbyen that the Marauders encountered him. The 2nd Battalion had closed in on the position early in the day and the 3rd Battalion by its end. The I&R (Intelligence and Reconnaissance) Platoon of the 1st Battalion’s Red Team, under Lieutenant Sam Wilson, picked a suitable drop site and laid out the panels for C-47 transport planes, enabling the first of many resupply drops to be successful.

The Marauders made a good impression on Stilwell, but it seemed, as he didn’t wear rank insignia or special uniform items, it was not entirely mutual. One Marauder, unaware it was Stilwell, was overheard referring to him as looking like a “duck hunter.” To his credit, Stilwell just laughed.

February 22 was a welcome rest day for the Marauders at Ningbyen. The sound of Japanese artillery engaging the Chinese units could be heard in the distance. Equally noticeable to some of the unit was the stench wafting from unburied Japanese corpses nearby.

Lieutenant General Stilwell explained to Merrill that he wanted the Marauders to take to jungle paths going around the Japanese positions. The Marauders would then act as a maneuver element for the main Chinese attack on Maingkwan down the road through the Hukwang Valley and then farther along to Walabum to block the expected Japanese retreat. Merrill briefed his staff on the morning of the 23rd, and a final air resupply was received.

Early the next morning, led by their respective I&R platoons, the battalions moved out on the faint, occasionally undiscernible jungle paths that became their trails to battle in Burma. Stilwell’s primary order to Merrill was that the road leading south out of Walabum—occupied by the Japanese 18th Division, the conquerors of Singapore—was to be cut by his troops by March 3.

The battalions left several hours apart on the primary trail, turning off at different points toward and beyond the flanks of the Japanese force occupying Walabum. The Chinese 38th Division, along with the 1st Provisional Tank Group advised by Americans, would attack the Japanese main force around Maingkwan. They would then move directly toward Walabum once roadblocks were established to the south along with positions to the east and west, thus forming a net in which Stilwell planned to snare the Japanese.

It is important to note that with the attack on Walabum and in successive actions by the Marauders, Stilwell’s concept of a long-range penetration group differed significantly from that of Orde Wingate.

Major General Wingate planned for the various Chindit units to be dropped far behind enemy lines and operate independently. They would aid the main British units by attacking supply lines and disrupting communications, but essentially acting beyond the reach of their support. The Chindits’ planned disruption of the Japanese rear would cause confusion and possible diversion of Japanese troops from the front lines, but there would be little tactical interplay between their efforts and the British units.

In Stilwell’s eyes, the Marauders were to be used directly to optimize the attacks of the two Chinese divisions and the tank unit under his command. They were to maneuver through the jungle and around the Japanese forces occupying objectives targeted by the Chinese, and so disrupt any relief forces and the withdrawal of the Japanese.

Thus the positions taken by the Marauders and the timing of their attacks would be directly tied to the Chinese efforts. While the Marauders moved independently, their actions would be in concert with the Chinese, and the battalions could band together when necessary to reinforce each other.

The differing visions of the two commanders regarding long-range penetration would become critical to the Chindits at a later stage in the Allies’ 1944 Burma offensive after Wingate was killed in a plane crash on March 24 and Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten handed command of the Chindits to Stilwell.

However, as the Marauders entered the Burmese jungle on the morning of February 24, the Chindits had not yet begun to fly in. Their entry on American C-47s and glider aircraft would not begin until March 5.

THE BATTLE OF WALABUM

The Marauders commenced their trek around the main Japanese positions. Communications were at times difficult. While tracking the progress of the Chinese units on a daily basis, Stilwell only mentions the Marauders sporadically in his diary. He still used the term “the 5307th” or just refers to Merrill as “M,” and at one point, unsure of the Marauders’ movements and Merrill’s whereabouts, he wrote “?” Later in the campaign, communications would improve so the Marauders could clear rough airfields for single-engine L-4 liaison planes to fly in and pick up the wounded.

The first major enveloping movement by the Marauders would set the pattern for subsequent actions. Although there were skirmishes with the Japanese—basically squad and platoon actions along the way—the battalions kept moving.

In an early skirmish the Marauders suffered their first casualty, Private Robert Landis of Mahoning, Ohio, a veteran of fighting in the Solomon Islands, killed while walking point for an I&R platoon.

Their fitness and discipline enabled the Marauders to move quickly through the jungle, with the 3rd Battalion covering 18 miles in 11 hours early on March 2. On March 3, Merrill radioed Stilwell to say he would have units in place blocking the road south from Walabum at noon. The Marauders would attack Japanese units on March 4 as part of coordinated Chinese and American pressure on enemy positions north, east, and west of the town. As Stilwell noted in his diary, “The net is set.”

Using the Marauders as a maneuver element quickly bore fruit for Stilwell. Once aware of the American unit to the rear of his forces at Maingkwan (north of Walabum), the commander of the Japanese 18th Division, General Shinichi Tanaka, ordered units of the 55th and 56th Regiments to move south and “destroy” the Americans threatening his flanks. Thus, as the net closed, the Marauders encountered Japanese units up to battalion strength, and skirmishes at times became pitched battles. However, the Marauders’ training in unit maneuvers and their adaptation to local terrain gave them the advantage.

The I&R Platoon of the 3rd Battalion under Lieutenant Logan Weston had moved west across the Nambyu River toward Lagan Ga on the road north of Walabum late on March 3 and had spotted Japanese moving in the area. Early on the morning of the 4th, the platoon moved to high ground and dug in. Almost immediately, they received mortar fire and were attacked by a Japanese unit superior in size, sustaining several casualties.

Mortar support from the 3rd Battalion forces still on the other side of the river reduced the pressure of the Japanese attack, and Weston directed his platoon to cross back to the east bank. As the I&R Platoon initiated the crossing under fire, another 3rd Battalion platoon under Lieutenant Victor Weingartner took up position on the high ground above the east bank to provide cover, firing at the pursuing Japanese soldiers.

The Japanese troops plunged into the river to complete their pursuit, but the accurate fire of the Marauders above them killed many and forced them to abandon their chase. The I&R Platoon was able to cross without further casualties, though two of the wounded died later in the day while being evacuated by air.

Quick support for the I&R Platoon by other Marauders had not only saved the situation that morning, but also set the stage for a mass killing of Japanese in the next days.

From the high ground east of the Nambyu River, the 3rd Battalion and its mortar crews under Lt. Col. Charles E. Beach had a commanding view of Walabum, the road north to Maingkwang (where the main Chinese assault was taking place), and the road south to Kamaing (the Japanese 18th Division HQ).

These routes were key for the enemy to either summon reinforcements for battles north of Walabum or for a possible retreat. Under mortar fire from the high ground, it became obvious to the Japanese command that they had to dislodge the occupiers. The following day, March 6, elements of the Japanese 56th Regiment attacked the 3rd Battalion’s Orange Combat Team.

The Marauders were well dug in and expecting the attack. They had the advantage of higher ground, with the river to their front and an open field on the far side providing a clear firing view of the enemy advance. Nonetheless the Japanese commander followed orders to “destroy the enemy” and launched two attacks, the first early in the morning and the second late in the day. Both resulted in carnage.

The Marauders were amazed by courage of the Japanese troops amazed as they continuously ran to their deaths across the field and into the river. Hundreds of Japanese soldiers were killed (Merrill reported 300 to Stilwell though other reports cite 400). By sunset only seven Marauders had been wounded. The Japanese officers committed their troops to these suicidal frontal assaults with little attempt to maneuver around the Marauders’ flanks.

In the quiet of the night, Merrill sent word for Beach’s 3rd Battalion to withdraw. The Chinese, supported by a tank unit with American advisers, had broken through at Maingkwan and were approaching Walabum, which they would occupy the next day. The fighting wasn’t over, but the battle for Walabum was decided and the Marauders had written the first chapter of a remarkable combat story.

Now it was time to move to the Mogaung Valley farther south along the road to Kamaing.

THE BATTLE OF SHADUZUP

Lieutenant Colonel William L. Osborne’s 1st Battalion took the lead as the Marauders moved south toward Shaduzup, again acting as a maneuver force supporting the main Chinese attack. The Chinese force was to head south from Walabum and attack at Jambu Bun, 25 miles before Shaduzup on the Kamaing-Maingkwan road. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions were to swing farther south through the jungle, bypass the 1st Battalion, and set up roadblocks closer to Maingkwan.

The Marauders left the Walabum camp on March 12; the 1st Battalion aimed to be in position at Shaduzup on March 24. They had enjoyed five days of rest in the camp, but an occurrence there would cause the Marauders more casualties than all the combat with the Japanese put together.

They camped in the same area as the Chinese, who had no concept or training in the importance of field sanitation. To the disgust of the Marauders, the Chinese troops, peasants all, defecated whenever and wherever the spirit moved them, including the streams and river. Although the Marauders treated their water with halazone, it was insufficient to kill the microbes the Chinese soldiers were sharing with them.

Soon the first cases of amoebic dysentery appeared among the Marauders to complement the malaria they were already fighting. With time, this would permeate throughout the battalions with terrible effect.

The 1st Battalion made quick progress leading the way to Shaduzup for the first two days, but then started encountering Japanese ambushes. Enemy resistance continued to grow until Osborne realized his men would have to fight their way down the trail on a daily basis, and thus could neither reach their objective on time nor be in a condition to place an effective roadblock on the road south of Shaduzup. He decided the battalion had to push cross-country around the Japanese in an effort to achieve the target date of March 24.

A critical asset for the Marauders moving through jungle terrain with inadequate maps were the friendly Kachin tribespeople serving as scouts and guides. The Japanese troops had killed and tortured many Kachin people; consequently, the Kachins were highly motivated to help the Yanks.

The Marauders, and the OSS 101st Detachment active in north Burma, praised them and recognized the importance of their service. Even so, progress through thick jungle and dense bamboo over rough, steeply undulating terrain was mercilessly difficult. Units were rotated to cut trails with machetes but still became exhausted and the Marauders fell behind schedule. Food and fresh water were in critically short supply.

On the 17th they received an airdrop of supplies and resumed the trek, but now dysentery was sweeping the unit. On March 22, Stilwell noted in his diary that he “waited for news of the 1st Bn … off on a new trail.”

In the original February movement and the subsequent battle for Walabum, the presence of the Marauders to their rear had surprised the Japanese. Now, Japanese commanders took measures to increase their flank security, and as the days passed and the battalion pushed farther southwest through the jungle toward the road south of Shaduzup, it encountered increasing numbers of enemy troops and engaged in short, fierce firefights.

Lieutenant Colonel Osborne devised a tactic to deceive the Japanese and take the pressure off the main battalion units as they advanced toward the road. He sent a platoon under Lieutenant John McElmurray to the northwest, away from the battalion, to fire on Japanese soldiers on the road above Shaduzup and draw their commander’s attention away from the main thrust of the Marauders.

The plan worked, as McElmurray’s platoon fired on and killed a Japanese soldier on the road and then drew mortar fire from enemy units in the area.

On March 27, Osborne had his 1st Battalion in place along the east bank of the Mogaung River, paralleling the road from Shaduzup to Kamaing that ran west of the river and was occupied by Japanese units.

Acting on a scouting report received from two brave I&R Platoon members, who had crossed the river late in the day to map enemy positions and then discovered a Japanese camp, Osborne drew up a plan for his White Combat Team to start crossing the river at 3 amon the 28th and attack the camp. By 4:30 amthe unit was in position on the west side of the river.

The Marauders attacked the sleeping Japanese soldiers and completely routed them, killing many while the rest ran off into the jungle. At first light the Marauders set up their roadblock, effectively blocking any Japanese reinforcements from coming north up the road to Shaduzup, which was now under attack by the Chinese 22nd Division.

The Marauders who had established the roadblock were essentially trying to hold a fixed position of no tactical advantage and for which the Japanese artillery had clear coordinates. Artillery fire started falling at dawn and continued throughout the day. The Japanese had 75mm howitzers and 77mm mountain guns, and they continued to barrage both the roadblock and the rest of the 1st Battalion dug in on the east bank of the Mogaung River. The Marauders had no artillery with which to fire back. After enduring the barrage into the evening, the Marauders drew back later that night.

The next morning, March 29, the Chinese 113th Regiment, which had been following the Marauders as backup, appeared with four howitzers and put the Japanese under fire. Then the Chinese infantry attacked. The Japanese forces, from Jambu Bun to Shaduzup, were running. The battle for Shaduzup was over.

The 1st Battalion had given an excellent account of itself. Osborne estimated the number of Japanese troops his men had killed at around 300. Their own casualties were eight killed and 35 wounded. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions, much farther south on the road to Kamaing, were also actively engaged with the Japanese during this period.

THE BATTLE OF INKANGAHTAWNG

The Marauders’ 2nd and 3rd Battalions had started out on March 12, the same day as the 1st Battalion, but had taken a wider arc, aiming to emerge from the jungle at the village of Inkangahtawng about 15 miles south of Shaduzup.

Merrill accompanied these units, which were guided not only by the Kachin scouts, but also by two Westerners who had lived in Burma for years and knew the jungle trails well—Jack Girsham, a British/Burmese hunter, and Fr. James Stuart, an Irish missionary. They moved along a well-defined ridgeline far enough from the road to avoid encountering Japanese troops.

The two battalions moved quickly, overtaking the impeded 1st Battalion, bypassing Shaduzup, and taking up position within a day’s march of the road and Inkangahtawng by March 20. Here, Merrill decided to divide his force. He would remain behind at Janpan with the Orange Combat Team of the 3rd Battalion and the OSS 101st Detachment of 300 Kachins, who had been there on their arrival, while he sent McGee’s 2nd Battalion and the Khaki Combat Team of the 3rd Battalion onward to set up a roadblock south of Inkangahtawng under the command of Colonel Hunter.

The diary note made by Stilwell on March 22 reflected Merrill’s plan for the division of his forces: “M … says his movements will look cock-eyed, but never mind. He’s bluffing > Kamaing & going by at night.” Whatever the plan, Merrill was definitely putting the Marauders’ 2nd and 3rd Battalions farther out on a limb with this extended movement without backup while the 1st Battalion was completely engaged at Shaduzup. The Marauders were spread over a 30- to 40-mile loop well behind enemy lines.

Colonel Hunter moved his troops south that same day with the Blue Combat Team of the 2nd Battalion leading the way. They camped at the village of Nhpum Ga the first night. Moving through Auche the next day, the 21st, Hunter arranged a resupply and received radio orders from Merrill to move fast as the Japanese were withdrawing in front of the Chinese at Jambu Bun.

On the 22nd, Hunter’s detachment of Marauders moved back into the valley toward the road used by the main Japanese units. They were forced to leave the ridgeline, trek down a steep jungle trail, and then move along a narrow river from one steep bank to the other in an exhausting exercise.

The troops eventually encountered flat land near the village of Manpin late in the day. Hunter organized a resupply drop then told McGee to take the 2nd Battalion together with the Khaki Combat Team and push five miles farther on to Sharaw. The Marauders walked until 11 pmand then camped. It was raining heavily.

The next morning, Hunter ordered McGee to continue forward to set up the roadblock six miles south of Inkangahtawng. He remained at Sharaw with the 3rd Battalion’s Orange Combat Team in reserve.

With the Blue and Green I&R Platoons in the lead, the 2nd Battalion crossed to the west bank of the Mogaung River. The Khaki Combat Team, with the mortars and mules, kept position on the east bank of the river. The two I&R Platoons separately encountered Japanese units near the road, and both began firing between 4 pmand 5 pm.

The I&R teams then withdrew to join their combat teams dug in on the west bank of the Mogaung some 300 yards from the road. The 2nd Battalion was unexpectedly isolated in Stilwell’s overall attack. The 1st Battalion had yet to launch its assault near Shaduzup to the north, leaving the 2nd Battalion as the only unit to occupy the attention of the Japanese command as a threat to their forces on the road above their headquarters at Kamaing.

In their night position near Inkangahtawng the Marauders could hear trucks pulling up on the road in front of them and Japanese troops noisily talking as they unloaded. They expected the Japanese to attack in the morning light of March 24.

However, when morning came and the Marauders sat in their positions enduring the continuing downpour, there was no attack. A platoon was sent forward under Lieutenant Ted McLogan that soon encountered a Japanese patrol and fired on it. After dispersing the first group of enemy soldiers, McLogan’s men continued patrolling along the road where they found another group and took them under fire as well.

McGee called McLogan on the radio, received the situation report, and told him to return to the battalion position, which he did immediately.

Then the Japanese attacks started. First, a mortar barrage and then, from the elephant grass to the Marauders’ front, Japanese soldiers rose screaming in a banzai charge. These soldiers were shot down with automatic weapons fire, and the attack failed. Moments later in a different sector of the perimeter another banzai attack was launched—this time across an open field. This attack was also mowed down, and the front of the Marauders’ position was now littered with Japanese bodies to the extent they had to be moved aside to maintain fields of fire.

Afterward the Marauders commented on the fanatical bravery and determination of the Japanese troops, but one Marauder also took into account the extensive use of amphetamines by the Japanese Imperial Army whenever they went into battle and noted, “They must have been doped up.”

The mortar fire falling on the Marauders’ position continued, though slackening at times. As the day wore on, the Japanese attacked repeatedly, shifting points of attack around the 2nd Battalion’s perimeter and searching for a weak spot. For some reason, the Japanese only attacked in groups of 10 to 40 men at a time, never really massing their forces. The banzai attacks continued throughout the afternoon.

McGee, out of contact with Colonel Hunter who had radio problems, sent a message to Merrill telling him his unit was running low on ammo and was ordered to withdraw to the east bank of the Mogaung River and tie up with the Khaki Combat Team of the 3rd Battalion. Under cover of a P-51 air strike on the Japanese positions and then a mortar barrage from the Khaki Combat Team, the 2nd Battalion withdrew across the Mogaung in the late afternoon.

They had fought off 16 banzai attacks, killed an estimated 200 Japanese, and were completely exhausted, but they were able to rest for only a few hours. Brig. Gen. Merrill radioed McGee that more Japanese troops were on their way toward them and they should withdraw.

At 5 amon March 25, they withdrew from the Mogaung River site, moving through a torrential rain back up the trail on which they had arrived, to the village of Sharaw where Hunter was camped. Hunter had been out of communication with McGee and was at first unaware of the extent of the 2nd Battalion’s action. When he learned of Merrill’s order for McGee to pull back, he took exception to it. At Sharaw he confronted McGee, who said he was going to continue drawing back according to Merrill’s order.

Conscious that Japanese forces would be coming after them, on March 26 McGee led his men back toward Auche and the north-south ridgeline that the Marauders had traveled along a week earlier. Colonel Hunter, who still disagreed with the withdrawal but felt forced to accede to Merrill’s orders, followed with the 3rd Battalion.

It was Hunter’s opinion that the Marauders should have been attacking, not withdrawing. He doubted the presence of greater numbers of Japanese troops and felt they were missing an opportunity to strike at the weakened Japanese headquarters position farther south at Kamaing. He radioed Merrill requesting permission to attack with the 3rd Battalion but was ordered to withdraw.

Hunter was mistaken, and Merrill’s caution in the matter was definitely correct. There were many more Japanese troops closing in on the Marauders than just the force following the 2nd Battalion up from Inkangahtawng.

The 3rd Battalion commander, Lt. Col. Beach, had earlier had the good judgment to dispatch two platoon patrols to set up blocks to protect the flanks of the 2nd Battalion as it withdrew to Sharaw and then Auche. The I&R Platoon of the Orange Combat Team under Lieutenant Logan Weston had set a block at Poakum seven miles north of Kamaing, and a rifle platoon of the Orange Combat Team under Lieutenant Warren Smith had set a block on the Warong road.

The I&R Platoon was in place on March 24 when a Japanese patrol appeared; the platoon opened fire and killed them all. Another Japanese patrol arrived with scout dogs; they, too, were wiped out. The Marauders received mortar fire but remained in position, blocking the trail throughout the night.

Receiving more intense mortar fire and signs of a flanking movement the next morning, Weston decided to pull his platoon back up the trail. He encountered Lieutenant Smith’s platoon, which shared ammunition with them and, calling Merrill, received approval for both platoons to withdraw along the trail, exchanging positions to defend each other against Japanese flanking movements while delaying any movement by the Japanese against the 2nd and 3rd Battalion withdrawal.

On the following day, March 26, they withdrew in the dark, leaving some small campfires burning to fool the Japanese. A few hours later, dug in higher up on the trail, they heard the sound of shooting as the Japanese attacked the camp they had abandoned, firing into their own forces. The same morning Lieutenant Smith and his platoon ambushed another Japanese force advancing toward them, killing 28.

That afternoon Weston and Smith agreed on a full pullout to avoid encirclement by the Japanese, withdrawing all the way back to Auche, where they dug defensive positions and waited for the 2nd and 3rd Battalions to arrive from Manpin.

The initiative of these junior officers and their brilliantly executed joint movements and tactics had delayed the large Japanese force intent on catching the Marauders’ battalions on the trail and doubtless saved many lives.

However, for the Marauders, a unit that specialized in fire and maneuver, possibly the main encounter of their campaign, an epic defensive struggle, was now at hand.

THE BATTLE OF NHPUM GA

Ever since the Marauders entered the jungle from Stilwell’s headquarters on February 24, Merrill had moved aggressively and spread his troops across a wide network of trails behind the Japanese lines, surprising and killing hundreds of enemy troops.

In response, the Japanese commander withdrew battalions from his front lines to counter the threat to the rear. The unsupported Marauder battalions, far to the south of the main Chinese attack and the 1st Battalion action at Shaduzup, were to be caught out now by superior numbers of Japanese and their artillery.

The village of Nhpum Ga lay four miles north along the trail from Auche. It was the site of Merrill’s headquarters when Lt. Col. McGee’s 2nd Battalion, followed within hours by Colonel Hunter and the 3rd Battalion, entered Auche on March 27. Merrill ordered the 3rd Battalion to push through Nhpum Ga, a high point on the trail, and continue another four miles to Hamshingyang, 1,500 feet lower in altitude. An open valley adjacent to Hamshingyang would serve well as an airstrip.

On the 28th, the 2nd Battalion started its move from Auche to Nhpum Ga with the Japanese harassing them close behind. Several machine-gun teams set up stay-behind positions on the trail, ambushing Japanese scouts and delaying the Japanese units. Later, the Japanese directed artillery fire on the 2nd Battalion’s line of march. By the afternoon the battalion had closed on Nphum Ga and started to prepare defensive positions so they could hold the hilltop against attack.

But a major setback took place. Merrill was struck by a heart attack. He was moved with the 3rd Battalion to Hamshingyang and was evacuated the next day. Leadership of the Marauders now rested with Colonel Hunter.

Throughout the day and evening, Japanese units moved up and surrounded the positions of McGee’s 2nd Battalion at Nphum Ga. The stage was now set for the most vicious fight the Marauders would endure in Burma.

The Marauders had the advantage of a plentiful supply of machine guns and automatic weapons (BARs, Thompson sub-machine guns, and M-1 carbines), exceeding the normal infantry unit allotment. They needed all their firepower in the next 12 days.

The 900 men of the 2nd Battalion, including muleskinners, medical, and communications teams, continued digging into the hilltop position on the 29th, preparing for the Japanese attack. The north-south perimeter was some 400 yards long with a shorter east-west axis. There was a water hole within the perimeter.

Hunter visited to observe the setup and arranged immediate airdrops of food and ammunition. Promising McGee there would be active patrols on the trails between the two villages to prevent Japanese flanking moves, he then left for Hamshingyang and the 3rd Battalion HQ. From there Hunter radioed the 1st Battalion, then pulling back from Shaduzup, and ordered Osborne to start moving toward Hamshingyang.

At dawn on March 30, the Japanese launched the first of many banzai attacks against the Marauders’ positions at Nhpum Ga. This followed an artillery and mortar barrage and set the theme for the following 12 days.

The Japanese artillery pounded the Marauders’ positions, pausing only occasionally. The mortar fire was constant. The horses and mules, out in the open, were early casualties, and their decomposing bodies would lie there throughout the siege. The men fought off banzai attacks on different points of the perimeter. In an early attack, the Japanese managed to capture the water hole.

Trapped in their foxholes, the men used their helmets to relieve themselves, throwing the contents outside when possible. Two Marauders scouting Japanese positions were killed by friendly fire while trying to return to the perimeter.

Attempts were made by 2nd Battalion patrols to attack north along the trail toward the 3rd Battalion, which also sent patrols south back toward Nhpum Ga. But both patrols were turned back by heavy Japanese fire from prepared positions.

The Marauders at Nhpum Ga were encircled. At the end of the day, McGee reported to Hunter that he had three dead and nine wounded.

On April 1 it rained heavily, allowing the Marauders, now short on water, to catch some rainwater in their ponchos. There were no attacks on the village, and McGee received the good news from Hunter that two 75mm howitzers would be brought to Hamshingyang the next day to provide support for the troops at Nhpum Ga. The Orange Combat Team of the 3rd Battalion attacked up the trail toward the 2nd Battalion defensive positions but was beaten back by the Japanese.

On April 2, the Japanese renewed their attacks on Nhpum Ga. Again the pattern was a series of assaults supported by artillery and mortar fire on differing points on the perimeter. All were repulsed. In the middle of the day during a lull in the fighting, the 2nd Battalion received a necessary air resupply of ammo and rations but no water, which they needed desperately.

April 3 was a day of constant shelling by Japanese artillery. Any infantryman who has lived through such an experience can testify to the terror induced by the whistle of shells and their earthshaking explosions as he cowers in his inadequate foxhole. A medic and two doctors crawled from foxhole to foxhole to treat the wounded, exposing themselves to sniper fire. That day the 2nd Battalion had six men killed and a dozen wounded. They needed the 3rd Battalion to come to their rescue.

The next day the main fighting shifted to the 3rd Battalion, trying to fight its way up to the 2nd Battalion’s position. In the afternoon, the two 3rd Battalion combat teams attempted to break through. The Orange Combat Team attacked straight up the trail with the two 75 mm howitzers, parachuted in earlier, firing point-blank in support. The Khaki Combat Team swung through the thick jungle trying to loop around the Japanese blocking force.

Because of the dense jungle and the camouflaged positions of the Japanese, the combatants were often less than 30 yards apart when firing at each other. The men of the 2nd Battalion, still under artillery fire, could hear the roar of the fighting along the trail and off to the sides in the jungle as both the Marauders and the Japanese tried to turn the flanks of the other. The 3rd Battalion moved closer but was still a mile away. Colonel Hunter radioed the 1st Battalion to move as quickly as possible to come to their aid.

At dusk the Japanese began another series of attacks on the 2nd Battalion positions, again shifting their attacks around the perimeter. Many of the Marauders were now so ill with dysentery or disease that they couldn’t stand. The lines were so close that one of the Nisei interpreters with the 2nd Battalion, Staff Sgt. Roy Matsumoto, overheard the Japanese discussing their forthcoming attacks and was able to alert the targeted sector. The attacks were repulsed. The Marauders had survived the day, but McGee sent a message to Hunter, “Please hurry.”

During this period of heavy engagement, there was no mention of the Marauders’ efforts in Stilwell’s diaries. Meetings in China and then India occupied Stilwell’s time. He didn’t return to his headquarters in Burma until late on April 3. His first diary note regarding the Marauders is for April 4, when he mentions a “disturbing msg. from Hunter” the previous night.

On April 5, the battle focused on the 3rd Battalion force attempting to relieve the Marauders at Nhpum Ga. They were in a reverse tactical position to their brothers of the 2nd Battalion in that the Japanese troops blocking their rescue attempt were dug in, and it was the 3rd Battalion troops who had to expose themselves in the attack.

In the thick jungle the fighting was at close range again, with only 20 to 30 yards separating the contending forces, and the firing was intense. By the end of the day the 3rd Battalion had advanced only 300 yards.

On the hilltop at Nhpum Ga, Staff Sgt. Roy Matsumoto again distinguished himself, crawling forward into the jungle from the defense perimeter and overhearing Japanese troops discussing the following morning’s attack on his sector of the defense line. With this information Lt. Col. McGee was able to shift resources to that side of the perimeter, and when the attack came early on April 6 it was handily repulsed. The remainder of the day was quiet on Nhpum Ga, and the Marauders thankfully received a resupply drop that included their desperately needed water.

Following a barrage from their two supporting artillery pieces, the 3rd Battalion continued to attack up the hill toward the embattled 2nd Battalion on Nhpum Ga and by the end of the day had moved to within 500 meters of their perimeter.

The lines did not move on Good Friday, April 7, but something more important happened. By the day’s close, after five days of forced march, the 1st Battalion arrived at Hamshingyang. They were 800 strong though in very poor condition, having had little to eat on their push to aid their brothers. Many were suffering from malaria and dysentery so severe they had cut holes in the seats of their pants so they could continue marching without stopping.

Plans were made to make a flanking attack on April 8 with a hand-picked team of more than 250 of their strongest survivors.

The frontal assault on the 8th was once again led by the I&R Platoon of the Khaki Combat Team. In slow going it suffered nine casualties. The two howitzers were moved up the trail on the backs of mules and reassembled within 700 meters of the Japanese, just a few hundred meters short of Nhpum Ga. The crews threw over a hundred rounds almost point blank into the enemy positions.

The 1st Battalion team undertook a long flanking movement around the west of the Japanese positions and turned toward the hill at sunset. They could hear gunfire from up above and smell the stench of the dead. Blocking positions were set up on several trails, including the one leading back to Kauri, the Japanese resupply base. The unit then camped for the night.

Even though the Japanese positions had been pounded hard, the 3rd Battalion had not broken through during the course of the day. However, the men of the 2nd Battalion were still dug in and holding on.

As dawn broke on Easter Sunday, the Japanese were not firing on the 2nd Battalion so Lt. Col. McGee decided to send out a patrol. They encountered one Japanese soldier and shot him.

Following behind a mortar and artillery barrage, a patrol from the 3rd Battalion moved up the hill through a shattered landscape littered with Japanese bodies, piles of which were “stacked like cordwood” according to one observer.

A patrol from the Orange Combat Team encountered a Japanese machine-gun position. One Marauder was killed before they moved on. At noon, Lt. Col. McGee was able to record in his diary that the relief troops from the 3rd Battalion had arrived. The surviving Japanese had withdrawn, probably due to the flanking movement by the 1st Battalion on top of the battering they had taken on previous days. The 12-day siege of Nhpum Ga was over.

The troops who had come to the aid of the 2nd Battalion were sickened by the carnage they encountered and the stench of the maggot and blowfly-encased bodies, including many horses and mules. The toll of Japanese amounted to 400. The Marauders lost 57 dead and 302 wounded, excluding those almost completely disabled by disease. Many of the 2nd Battalion survivors were shell-shock cases, still sitting in their foxholes in a daze.

The 2nd Battalion had buried their dead on the hilltop, but the bodies were exhumed and reinterred ceremonially in more fitting ground at Hamshingyang, alongside the respective burial plots for the 1st and 3rd Battalions.

All three Marauder battalions were exhausted and depleted of manpower. At Hamshingyang they finally had a period of rest. The improvised airstrip was busy, the wounded and sick were flown out, and resupplies of new uniforms, food, ammo, medical supplies, and mail were flown in.

Of the original 2,600 men who had marched into Burma on the Ledo Road in February only some 1,600 were still available for duty. The Marauders had been victorious on every occasion but had paid a steep price with many dead, wounded, or debilitated by disease.

Stilwell’s limited acknowledgement was a diary entry on Monday, April 10: “Npum (sic) has been cleaned up.” On April 11 he upgraded his comments to: “Hard fight at Npum (sic). Cleaned out japs & hooked up.—good job.” Amazingly faint praise indeed.

Though physically and emotionally depleted the Marauders rested, confident they had fulfilled their mission. The previous promises of 90 days of “dangerous and hazardous” combat duty followed by return to the United States were very much on the minds of most Marauders.

To a man they thought the time of their relief had come. So they were deeply disappointed and angry when word arrived that there would be no relief from combat, but rather they were to march on to Myitkyina. They correctly blamed Stilwell, and the hatred many of the Marauders held for him at war’s end started then.

Their final challenge, Myitkyina, awaited them. It was a bloodbath. In their final mission against the Japanese base at Myitkyina, the Marauders suffered 272 killed, 955 wounded, and 980 evacuated for illness and disease.

By the time Myitkyina fell, only about 200 surviving members of the original 2,600 Marauders answered the roll call. On August 10, 1944, a week after the town was secured by U.S. and Chinese forces, the 5307th was disbanded, with only 130 weary combat-effective officers and men left.

Merrill’s Marauders have gone down in history as an outstanding combat unit, but rarely has the price of fame and glory been so high.

The primary casualty evacuation planes that served the 5307th Composite Unit were Stinson L-1 Vigilant and L-5 Sentinel aircraft. While there were a few Piper L-4’s in theater they weren’t used as extensively in the evacuation role due to their low power and limited carrying capacity.

Heroic!! Horrible challenges to courageous U.S. men and Burmese allies