By Conan Brew

In the wake of the humiliating and unexpected defeat, and fourth in a line that stretched back to Fort Sumter, the Battle of Bull Run, and the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, the Union Congress created a seven-man Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War to oversee and review all battles and the events surrounding them. Ohio senator Benjamin F. Wade, a much-feared lawmaker known as “Bluff Ben” for his crass, take-no-prisoners demeanor, was named chairman. Other committee members included Michigan senator Zachariah Chandler, Tennessee senator Andrew Johnson, and Congressmen George Julian of Indiana, John Covode of Pennsylvania, Daniel Gooch of Massachusetts, and Moses Fowler Odell of New York. All except Johnson and Odell were Republicans.

The committee’s first act of business was to investigate what had gone wrong at Ball’s Bluff. There was much to investigate. With the Union Army’s commanding officer at the battle, Colonel Edward Baker, two months’ dead, attention fell on his immediate superior—Charles Stone. Meeting in secret for two months, beginning in late December 1861, the committee heard highly spurious testimony alleging that Stone was not merely an incompetent general, but a veritable traitor to the Union Army. Three dozen anonymous witnesses were called, many of them abolitionist-minded members of the Massachusetts regiments under Stone’s command who still bore grudges against the general for his order not to shelter runaway slaves in their camps.

Under orders to reveal exact troop numbers, locations, or tactics, Stone was reduced to giving a bare-bones account of the battle. He did himself no good before the committee by criticizing the martyred Baker’s conduct. “The whole story,” he said, “is that Colonel Baker chose to bring on a battle. He brought it on and, I am sorry to say, handled his troops unskillfully in it, and a disaster occurred which ought not to have occurred.” Given Baker’s posthumous standing as a Union Army hero—Lincoln, Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, members of the Cabinet, and a welter of senators and congressmen followed his casket for the first of Baker’s eventual three burials—such a statement, while true, made Stone seem petty and vindictive.

Charles Stone’s Downfall

The cards were stacked against Stone from the start. Following the committee hearings, the new secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, ordered McClellan to have Stone placed under arrest. No doubt relieved to have escaped—barely—his own censure for the fiasco at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, McClellan hastily complied. He used as his excuse a report he had received from an unidentified source in Leesburg that Stone had communicated with Confederate officers before the battle and “there was a general expression on the part of those rebel officers of great cordiality towards Stone.” It was implied that Stone had knowingly sent Union soldiers to their deaths at Ball’s Bluff. Taken away at bayonet point by Union soldiers in the middle of the night, Stone was imprisoned and held without formal charges for six months at Fort Lafayette in New York harbor. Despite his frequent pleas for a public forum in which to confront his accusers, he was denied a trial in open court. Letters to President Lincoln, Baker’s best friend, went unanswered or were passed off to other government and military authorities. It literally took an act of Congress, making it illegal to hold an officer under arrest for more than 30 days without trial, to gain Stone’s release. He had been held for a total of 228 days.

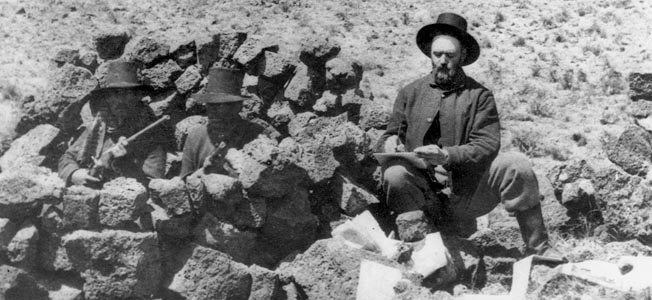

Returning to active duty, Stone sought unsuccessfully to resume his career. He was passed over repeatedly for promotion and never given another command. He served briefly on the staff of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks during the Port Hudson and Red River campaigns—still more Union debacles—before resigning his commission on April 14, 1864. After the war, Stone went into the coal mining business and then served for 13 years as a commander (pasha) in the Egyptian Army. He returned to the United States and worked as an engineer for the private construction company that erected the giant pedestal for the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor—not far from where he had been imprisoned so ignobly, more than 20 years before.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments