by Vince Hawkins

George Pommery Colley was born on November 1, 1835, in Dublin, Ireland. He was the third son of George Pommery Colley of Rathangan, County Kildare, Ireland. At age 13, after receiving a rather erratic education, Colley attended the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. He was then commissioned an ensign in the 2nd (Queen’s) Regiment of Foot in 1852. His first service was as a border magistrate in South Africa from 1854 to 1860. Colley was next transferred to China, where he saw his first action during the storming of the Taku forts on August 2. He then took part in the march on Peking and the capture of the city on October 6, 1860. Promoted to captain, Colley was subsequently reassigned to South Africa.

Of sharp mind, Colley tried to make up for his lack of formal education by reading and independent study. He studied science and political economy and learned to speak Russian. In 1862 Colley returned to England to attend the Staff College. Demonstrating a natural aptitude for military theory, Colley amazed his instructors and fellow officers by completing the entire two-year course in less than 10 months while still earning the highest marks recorded up to that time.

[text_ad use_post = “456”]

Breveted major in 1863, Colley then took a position at Sandhurst as Army examiner. In 1870 he was assigned to the War Ministry where he assisted in the preparation of Lord Cardwell’s army reform measures. In 1871 Colley returned to Sandhurst with an appointment as the professor of military administration at the Staff College. In 1873, now as a lieutenant colonel, Colley served in Sir Garnet Wolseley’s expedition during the Second Ashanti War where he was in charge of the expedition’s transport. He became close friends with Wolseley, who declared, “He was a man in a thousand, with an iron will and of inflexible determination.” In 1875 Colley was promoted to colonel and accompanied Wolseley on a visit to the Transvaal. He was appointed military secretary in 1876 and then private secretary to Lord Lytton, the governor-general of India.

In South Africa at the Start of the Boer Wars

In 1879 Colley returned to Natal where he was promoted to brigadier general and appointed Wolseley’s chief of staff during the final stages of the Zulu War. On April 24, 1880, he was promoted to major general and succeeded Wolseley as the governor of Natal and high commissioner for South East Africa. With this position also came the job of commander of all military forces in Natal. When the Transvaal Boers rebelled against English authority at the start of the Boer Wars, Colley took to the field and led operations against them.

Although a capable staff officer and administrator and considered “the best instructed soldier” in the British Army, Colley had limited combat experience and had never held an independent command. On this very point, in a letter to his wife, he stated his concerns over his first command by saying, “Whether I … shall find that South Africa is to me, as it is said to be in general, ‘the grave of all good reputation’s, remains to be seen.” His lack of command experience combined with his underestimation of Boer capabilities and their resolve for independence was to prove fatal.

Fatal Misjudgments

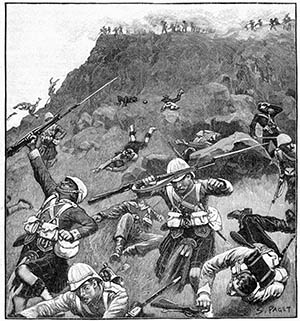

Leading an expedition to relieve besieged British garrisons, Colley first encountered the Boers at Laing’s Nek on January 28, 1881. He launched a frontal attack against the Boer positions which, owing in large part to the misjudgment of a subordinate, was repulsed with heavy loss. Continuing his advance, Colley was checked and defeated again at the Ingogo River on February 8, 1881. He then attempted a turning movement of the Boer flank by leading five companies of infantry to a position on top of Majuba Hill. Here, after a short, confused fight, Colley’s command was routed and he was killed.

Colley was a highly competent and talented staff officer who was looked upon by many of his contemporaries as a paragon of intelligence. Aside from his administrative talents, Colley was also well known for his considerable literary and artistic abilities—he read a great deal and developed a talent for drawing and painting.

Ambitious in his career goals, modest, charming, and chivalrous in his demeanor, Colley was also shy and sensitive, and a man in deep need of reassurance. Convinced of the superiority of the British soldier, he grossly underestimated the fighting capabilities and determination of the Boers. In considering his overall intelligence, his actions at Majuba Hill are all the more surprising, and numerous theories have been advanced to explain why he did what he did. Regardless of what Colley’s state of mind may have been on that unfortunate day in February, as historian Michael Barthorp put it, “the fact remained that he had gambled for high stakes and lost—his battle, his reputation, and his life.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments