by Roy Morris Jr.

The sudden wreck of the Whig Party in the 1850s led to the development of a new political party to contend with Stephen Douglas and the Democrats. Based solely in the northern half of the country, this political party also brought out of retirement an old and bitter enemy of Douglas—fellow Illinois politician Abraham Lincoln. As a one-term Whig congressman, Lincoln had opposed the previous war with Mexico and the subsequent spread of slavery into newly acquired territories. This opposition had cost Lincoln his seat in Congress and seemingly ended his political career. But the uproar over the Kansas-Nebraska Act brought Lincoln back into politics, and his highly publicized senatorial race against Douglas in 1858, although it ended in failure at the ballot box, had vaulted Lincoln into national prominence as one of the most eloquent and thoughtful spokesmen for the antislavery cause.

To Lincoln’s way of thinking, popular sovereignty was a fraud, a device for spreading slavery into “every part of the wide world.” It was true, said Lincoln, that people had the right to decide their local laws, “whether they were the oyster laws of Virginia, or the cranberry laws of Indiana.” But slavery was another matter altogether—it required deciding nothing less than “whether a Negro is not or is a man.” The Declaration of Independence had said that all men were created equal, and Lincoln followed that logic to conclude that “if the Negro is a man, there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.” Typical of Lincoln, he neatly summed up the major difference between the Republican and Democratic parties. “The Republicans inculcate that the Negro is a man; that his bondage is cruelly wrong, and that the field of his oppression ought not to be enlarged. The Democrats deny his manhood; deny, or dwarf to insignificance, the wrong of his bondage, and call the indefinite outspreading of his bondage ‘a sacred right of self-government.’”

[text_ad use_post=”455″]

That, in a nutshell, was what the southern delegates to the Democratic National Convention also believed, and what they demanded that their party’s nominee believe. Northern Democrats disagreed, not so much on the grounds of morality or humanity but on practical political grounds. Many of their constituents either cared very little about slavery, or else secretly shared Lincoln’s belief that it was a moral wrong. Douglas’s northern supporters particularly bridled at southern demands for a party platform plank endorsing the much-loathed Fugitive Slave Law, which required the federal government to actively assist in the capture and return of escaped slaves, or as southerners said, “persons and property.”

Lincoln and Douglas on Election Day

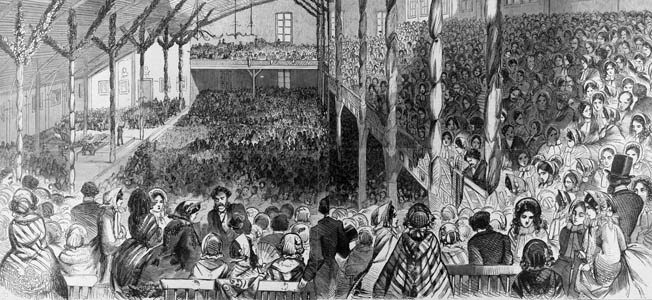

Election Day dawned on November 6. In Springfield, a relaxed and cautiously optimistic Lincoln spent the day in his office in the state capitol, then attended a covered-dish supper with his wife, Mary, at Watson’s Saloon, which had been taken over by local matrons and a more respectable clientele of local supporters. When Lincoln walked in, the women bowed and curtsied, calling out, “How do you do, Mr. President!” Loud cheers greeted each arriving telegram. “Not too fast, my friends, not too fast,” Lincoln cautioned. “It may not be over yet.”

Soon it would be. Mary Lincoln went home to look in on their sons, and the candidate went to the telegraph office, where word came in around midnight that he had carried New York State, giving him a sure 180 electoral votes. He would be the 16th president of the United States. The news spread as if by magic. Crowds spilled into the streets and climbed onto rooftops. Church bells clanged and cannons boomed in the village square. Lincoln put the historic victory telegram in his pocket for safekeeping and hurried home to tell his most loyal supporter the news. “Mary, Mary!” he called, bursting through the front door of their home on the corner of Eighth and Jackson Streets. “We are elected!”

A thousand miles away, in a newspaper office in Mobile, Stephen Douglas received the same news. He seemed oddly detached—the election returns showed why. Douglas had carried only one state outright—Missouri—and split New Jersey with Lincoln, giving him a pitiful total of 12 electoral votes. Breckinridge, who had scarcely campaigned, carried all the Deep South states, along with Delaware and Maryland, giving him 72 electoral votes. Bell’s Constitutional Union Party won the border states of Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, for 39 electoral votes. All the rest went to Lincoln. With 39.9 percent of the total vote, Lincoln’s winning margin was the lowest since John Quincy Adams was elected president in the disputed election of 1824. As southerners had intended—or at least expected—he was entirely a sectional president. Unfortunately for the South, that section was north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

“The Bright Sun Will Soon Chase Away These Clouds…”

Douglas tried to put the best face on the results. “This is no time to despair or despond,” he told a crowd in New Orleans, where he stopped en route back to Washington. “The bright sun will soon chase away these clouds and the patriots of this country will rally as one man and throttle the enemies of our country. Four years will soon pass away, when the ballot box will furnish a peaceful, legal and constitutional remedy for all the evils and grievances with which the country may be affected.” Already, there was talk of Douglas running again in 1864.

Whether there would even be a national election in four years was very much up in the air. “I think the Union is gone,” Douglas’s running mate, former Georgia senator and governor Hershel V. Johnson, told him. “With your defeat, the cause of the Union was lost.” The new president-elect continued to be almost blithely unconcerned. “The hot breath of secession,” Lincoln told his secretary, John Nicolay, “is just the trick by which the South breaks down every Northern man.” He did not intend to be similarly intimidated by the “political fiends” he saw at work in the South.

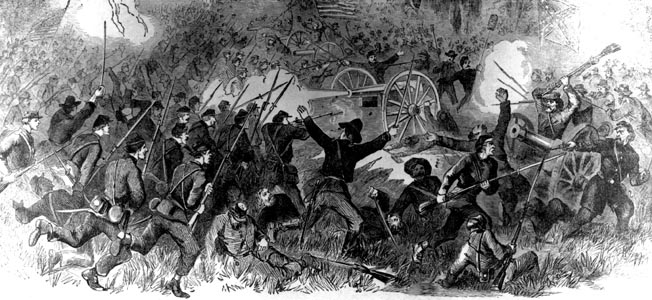

One of those fiends, the editor of the provocatively named Atlanta Confederacy, put the issue of Lincoln’s election in blunt and unmistakable terms: “Let the consequences be what they may,“ he wrote, “whether the Potomac be is crimsoned in human gore, and Pennsylvania Avenue is paved ten fathoms in depth with mangled bodies, or whether the last vestige of liberty is swept from the face of the American continent, the South will never submit to such humiliation and degradation as the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln.” It was a suitably ominous coda for the most divisive election in American history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments