By John Walker

When dawn broke on December 1, 1950, on the barren hillsides on the eastern shore of the frozen Chosin Reservoir in northeastern North Korea, the ragged, tenuously held perimeter of the U.S. Army’s Task Force Faith was a scene of utter desolation. The task force’s surviving members were on the verge of annihilation. The perimeter was little more than groups of starving, exhausted, and frostbitten American and South Korean soldiers, in varying numbers, huddled around campfires near the remaining artillery pieces and heavy weapons, trying to find warmth. Thousands of American, Chinese, and Korean frozen corpses lay strewn about the terrain, the detritus of sustained, vicious, close-in fighting. Frozen hands and feet were common. Some wounded men, who were unable to move, had frozen to death.

The American dead were from the previous night’s attack. The Chinese commander had exhorted his troops to wipe out the task force before dawn. The dead bodies were gathered in central collecting points. Survivors searched the bodies for ammunition, weapons, and clothing. Nearly 600 wounded Americans and South Koreans awaited evacuation at the overwhelmed aid station.

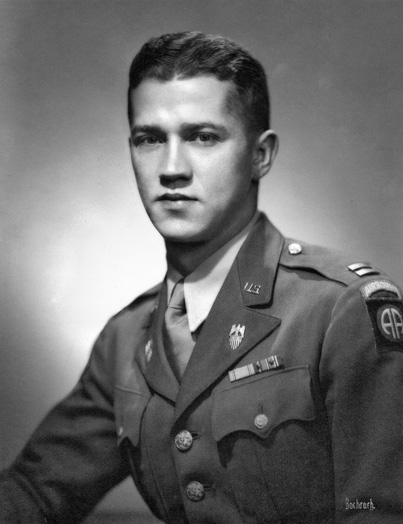

The men of the beleaguered regimental combat team had been under attack against overwhelming odds for 80 hours in the harshest, sub-zero weather conditions ever faced by American troops. Lt. Col. Don Carlos Faith had taken over command of the task force after the group’s commander, Colonel Allan MacLean, had been mortally wounded three days earlier.

Caught by surprise on the night of November 27, the understrength task force had suffered through four consecutive nights of repeated ground attacks. The Chinese had massed their troops in human waves and swarmed over American foxholes into the perimeter, fighting hand to hand, firing burp guns, and throwing hand grenades.

The depleted task force now was going to launch a last-ditch breakout attempt, their goal the U.S. Marine Corps perimeter at Hagaru-ru village near the reservoir’s southern edge, eight miles away to the southwest. Cut off by tens of thousands of enemy foot soldiers, perilously low on ammunition for their heavy weapons, and burdened by 600 wounded they would bring out with them, the task force’s chances seemed hopeless. Faith, however, and many of his men were convinced they could not survive another night of enemy mortar, machine-gun, and ground attacks. The believed the breakout attempt was their only hope for survival. Unfortunately, the weather appeared to be getting worse, threatening air cover for the breakout column and the promised airdrop for that morning, which would provide precious shells for the 40mm dual cannons and ammunition for the .50-caliber machine guns.

Events on the Korean peninsula unfolded rapidly in the months after June 25, 1950, the day North Korean armored forces rolled across the border into South Korea, shattering all resistance and bottling up United Nations and South Korean forces inside the Pusan perimeter. U.N. Supreme Commander General Douglas MacArthur’s strategic masterstroke, the unexpected and risky amphibious landing at Inchon on September 15, led to the recapture of Seoul two weeks later and effectively ended the North Korean invasion. Buoyed by visions of quick and total victory, U.S. President Harry Truman and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff endorsed MacArthur’s plan for a follow-on advance across the 38th Parallel to destroy what remained of the North Korean armed forces, end the war, and unify the peninsula under South Korean control. Two large U.N. armed forces would cross the 38th Parallel and attack in a giant pincer movement.

Red Chinese leader Chairman Mao Zedong, who had tacitly supported North Korea’s invasion, considered the movement of United Nations and South Korean forces across the 38th Parallel northward toward the Yalu River and the Chinese province of Manchuria as tantamount to an act of war against China. Chinese Communist Forces (CCF), including a number of experienced combat units from the recently concluded Chinese civil war, began marching south toward the border. On October 16, 1950, the CCF 124th Division of the 42nd Army crossed the Yalu River, adding another combatant to the Korean War. Tens of thousands of CCF troops infiltrated North Korea. They marched at night, hiding in the rugged, mountainous terrain during the day, awaiting the order to launch a massive counteroffensive against the U.N. forces’ two-front advance into North Korea.

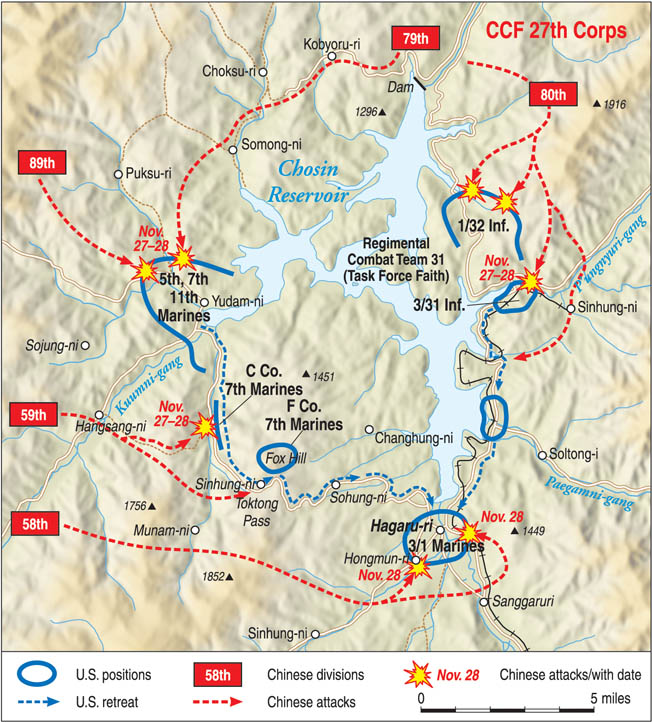

The western prong of the U.N. advance consisted of Lt. Gen. Walton Walker’s U.S. Eighth Army backed by four Republic of Korea (ROK) divisions and units from other U.N. nations. The eastern prong, which was separated from Walker’s forces by the Korean peninsula’s mountainous spine, the Taebaek Mountains, consisted of Maj. Gen. Edward Almond’s U.S. X Corps, made up of three American divisions and two ROK divisions. The three American divisions were the crack 1st Marine Division, the U.S. Army’s 3rd Division, and the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry Division. MacArthur’s strategy to end the war by Christmas called for Walker’s force to move north on November 24. Forty-eight hours later, Maj. Gen. Oliver Smith’s 1st Marine Division would strike west from the Chosin Reservoir and then north to the Yalu. Meanwhile, 7th Infantry Division forces, after relieving a Marine regiment on the reservoir’s east side, would attack on Smith’s right flank and advance to the Yalu. The 3rd Infantry Division would have the dual mission of providing rear security for the Wonsan-Hamhung corps base area on the Sea of Japan coast and sending a force northward on Smith’s left flank.

As the date for the massive offensive into North Korea approached, both Walker and Smith began to harbor strong misgivings about thinly stretching their units over such a vast expanse of territory. Walker tried several times to delay the inevitable by protesting the lack of logistical support and supplies that were en route from Japan and the United States, but all he accomplished was to increase MacArthur’s ire toward him and impatience at the delay. The Army’s 7th Infantry Division was not prepared for arctic warfare yet was ordered forward regardless.

Even as Almond urged Smith to get his division charging north to the Yalu River, Smith’s Marines began noticing ominous signs of activity around them, such as large numbers of deer moving down from the ridges. Before the battle erupted, Smith sent a letter to the commandant of the Marine Corps, stating his misgivings. “Our left flank is wide open,” he said. “I have little confidence in the tactical judgment of X Corps or in the realism of their planning.” These misgivings were quickly pushed aside. MacArthur’s promise to have the boys home for Christmas gave strong impetuous to the ill-conceived move to the Yalu River. Pressure to bring an early end to the war in one massive operation became too difficult to contain, especially in the aftermath of the Inchon victory.

Intelligence reports given to MacArthur and his intelligence chief, Maj. Gen. Charles Willoughby, indicated the presence and capture of Communist Chinese Forces (CCF) troops in late October and early November. A daily intelligence briefing in early November indicated a dramatic increase in combined North Korean and Chinese troop strength. The briefing put enemy strength somewhere between 40,100 and 98,400 men. As late as November 24, Willoughby estimated that no more than 34,000 Chinese were fighting alongside North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) units. These estimates did not seem to take into consideration that U.N. units had been bloodied in heavy fighting earlier that month against Chinese forces on both sides of the peninsula, and therefore the Chinese must have been heavily reinforcing the North Koreans.

Moreover, the Chinese soldiers already engaged were assumed to be merely stragglers or remnants fleeing north across the border, and therefore of no real significance. The true size of the CCF forces south of the Yalu River, which was 30 infantry divisions, had rapidly grown to at least 240,000 men and possibly as many as 300,000. A Chinese division at full strength numbered 10,000 men, but it is believed some of the divisions engaged in North Korea were understrength, and numbered between 7,000 and 10,000 men.

The CCF 13th Army Group, 18 divisions strong, was preparing to strike Walker’s front while the CCF 9th Army Group, 12 divisions strong, was about to hit Almond’s X Corps. Twelve under strength divisions of NKPA troops, having recovered sufficiently from their earlier reverses to be judged battle worthy, added 65,000 men to the enemy’s order of battle. Another 30,000 to 40,000 guerrilla fighters were operating behind U.N. lines in North Korea. MacArthur remained firmly convinced, despite evidence to the contrary, that the Chinese would not dare intervene in the Korean civil war. He assured Truman that the war “was already won” and that any Chinese divisions identified in North Korea would be quickly destroyed by American air power. In the wake of one of the most egregious command and intelligence failures in the history of American arms, a disorganized, hastily assembled, and understrength task force of U.S. Army soldiers from the 7th Infantry Division was about to be virtually abandoned on the barren eastern hills of northeastern North Korea in late 1950, sacrificed to the foolish haste and hubris of top U.S. Army commanders.

Several factors adversely affected the 7th Infantry Division when it deployed to South Korea in late 1950 and found itself facing a savage and tenacious enemy, extremely severe weather conditions, and overwhelming odds. The U.S. Army numbered 89 divisions at the end of World War II but then underwent a drastic reduction in size. By 1950, the 7th Infantry Division was one of only 10 active divisions in the Army. It was one of four understrength divisions on occupation duty in Japan, along with the 1st Cavalry Division and the 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions, when war broke out on the Korean peninsula. The 7th Division already was depleted by postwar shortages of men and equipment when its commander, Maj. Gen. David Barr, assembled the division at Camp Fuji. It was further depleted when it was ordered to send large numbers of its most experienced officers and noncommissioned officers to South Korea to strengthen the two American divisions already fighting there, reducing the division to 9,000 men, half its wartime strength.

To replenish its ranks, the ROK agreed to assign more than 8,600 poorly trained South Korean soldiers to the 7th Division. These troops were known as KATUSA, which stood for Koreans Attached to the U.S. Army. They had been rounded up in Pusan and Taegu and informed they were now members of the ROK army. The ad hoc task force that would be formed to participate in X Corps’ incursion into North Korea would be saddled with 700 of these augmentation troops, which Barr described as “stunned, confused, and exhausted.”

Under the emergency conditions of the war’s early weeks, there was no opportunity to properly train these men and they remained unpaid, separated from their families, poorly equipped, and indifferently supplied. Almost a quarter of the 7th Division was eventually composed of these ineffective KATUSAs, who tended to behave more like prisoners of war than soldiers.

After reinforcements arrived from the United States, 7th Division was slowly brought up to its normal strength, albeit with augmentation troops numbering more than 8,000 among its ranks. In the rush to comply with MacArthur’s orders for X Corps to deploy into northeastern Korea, the units of Task Force MacLean were given no stockpiles of ammunition, fuel, or rations. Nor had any effort been made by X Corps to issue winter clothing to the troops; MacLean’s men were outfitted in field jackets with flimsy pile liners and thin cotton trousers. The item most sorely lacking was the long, hooded, fur-lined parka. To make matters worse, the gross lack of preparation was evident in the virtually nonexistent radio communication equipment made available to the various units of the 7th Division. When it hastily deployed to the east side of the Chosin Reservoir, Task Force MacLean could not make radio contact with either the 7th Infantry Division’s headquarters at Pungsan or the Marines’ command post at Hagaru-ri village near the reservoir’s southern edge. When the order for the task force’s scattered units to converge at the reservoir came, they were isolated not only from the rest of the 7th Division and the 1st Marine Division, but also from each other.

On November 24, for better or for worse, Walker’s reinforced Eighth Army went on the offensive. On the night of November 25, the Chinese struck Eighth Army’s front with massive numbers of troops. With bugles blaring, tens of thousands of Chinese foot soldiers armed with burp guns and grenades swarmed the American, United Nations, and ROK positions. After several beleaguered units were overrun and nearly wiped out, Eighth Army was in full retreat south. The CCF onslaught, which cleared Walker’s entire command from North Korea and captured Seoul in the first week of January 1951, took MacArthur completely by surprise and instantly changed the tide of the war. It was clear that MacArthur had blundered badly in crossing the 38th Parallel. He had been outsmarted by a peasant army without air support or tanks, and hardly any artillery, whose communication and supply systems could only be called primitive. Despite the CCF attack, MacArthur decided that the X Corps offensive scheduled for November 27 would proceed according to plan.

Expecting to face only token resistance, Almond had begun his advance by fragmenting X Corps’ five divisions across an extended 500-mile front in northeast Korea’s rugged terrain. All of his forces, save the 1st Marine Division, were entirely focused on racing to the Yalu River, unaware that CCF divisions were about to strike. When Smith protested that his Marine division was becoming dangerously dispersed, Almond dismissed his concerns. Almond had already urged Barr to get his 7th Infantry Division units heading toward the Yalu as rapidly as possible. Barr and his staff, aware that Almond had been dissatisfied with the division’s performance during the September Inchon operations, were thus desperate to excel in their corps commander’s eyes.

Barr’s 7th Infantry Division, though, was totally unprepared to launch its proposed attack on November 27, since its 17th Infantry Regiment and 32nd Infantry Regiment, which constituted two-thirds of the division’s combat strength, were 80 air miles from the reservoir and approximately twice that distance by road. It would take days to redeploy the infantry regiments, along with their artillery and armor support, over the miserable clogged roads and prepare them for a major offensive. Barr’s advance was therefore postponed, but only for a day. Almond ordered Barr to strike north on November 28 with whatever 7th Infantry Division forces were available. When Smith wisely refused to launch his attack until 7th Division units had relieved the 5th Marine Regiment from its position east of the reservoir, and it could join the rest of his division, Almond, anxious to get the corps’ advance going, ordered Barr to rush his closest available units to the reservoir.

Brigadier General Hank Hodes, 7th Division’s assistant commander, would manage the redeployment to the east side of the Chosin from his command post at Hagaru-ri village. Since the bulk of the units would come from the division’s third infantry regiment, which was MacLean’s 31st Infantry Regiment, MacLean would exercise tactical command.

Under the ad hoc and hurried redeployment plan, Task Force MacLean comprised the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 31st Infantry (2/31 and 3/31); 31st Tank Company with 22 medium tanks; and the 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry (1/32) under Faith’s command.

The task force also included two batteries of the 57th Field Artillery Battalion (equipped with 105mm howitzers); one platoon of Battery D, 15th Antiaircraft Battalion; and the 31st Heavy Mortar Company. The 57th Field Artillery Battalion was composed of eight self-propelled antiaircraft vehicles, four of which were M19 fully tracked vehicles with dual 40mm cannons and four of which were M16 half-tracks boasting quad .50-caliber heavy machine guns.

Task Force MacLean numbered 3,200 men, 700 of whom were ROK augmentation troops.

One welcome addition to the task force was a four-man U.S. Marine forward air control team known as a tactical air control party, consisting of Captain Edward Stamford and three enlisted Marines. Stamford, who would receive a Silver Star for his heroic effort, was a tower of strength throughout the entire ordeal, calling in Marine airstrikes and supply drops, sometimes on the same radio frequency, and finding a way to maintain radio contact with the Marines at Hagaru-ri even after his primary radio equipment was destroyed by Chinese fire. On the first night of Chinese attacks, he assumed command of one of Faith’s rifle companies when that unit’s commanding officers were killed in action.

Moving north toward the reservoir over jammed, precarious, and icy roads, Task Force MacLean’s units made slow and difficult progress. Faith’s 1/32, whose starting position was closest to the reservoir, arrived first, while MacLean’s other units remained strung out in an eight-mile column on the road from Hamhung on the coast to Hagaru-ri. After relieving the men of the 5th Marines and occupying their positions, which were the farthest positions north on that side of the reservoir, Faith’s battalion was dangerously exposed and unsupported and went without artillery backup for a full day.

Even though other task force units were only slowly arriving, MacLean went forward and confirmed to Faith that their attack would go on as planned the next morning, November 28, spearheaded by Faith’s 1/32. Still absent from Task Force MacLean was 2/31, which constituted one-third of the task force’s infantry strength, while the 31st Tank Company remained well south of Hagaru-ri. Due to their deplorable communications, Faith’s men were out of radio contact with 7th Division headquarters, the Marines at Hagaru-ri, and all other task force units.

Since Faith’s infantry battalion had relieved the 5th Marines, General Smith had been able to launch the 1st Marine Division in its attack westward from Yudam-ni on November 27, but it was quickly halted by huge concentrations of Chinese troops. The Chinese units the Marines encountered were part of a six-division force then deployed around the reservoir, preparing for a surprise attack on the night of the November 27. The Chinese planned to hit the widely dispersed X Corps units everywhere simultaneously, isolate them, and then destroy them piecemeal. Three CCF divisions would target the Marines west (Yudam-ni) and south (Hagaru-ri) of the reservoir, while two more attacked farther south to isolate the Chosin area and cut off any retreat routes. The sixth division, the CCF 80th, would attack what the Chinese believed would be more Marines on the reservoir’s east side, but actually was Task Force MacLean. Faith’s 1/32 held its forward position, while two miles to the south 3/31 and two artillery batteries had hurriedly created a perimeter on poor defensive ground at the Pungyuri Inlet. A couple of miles farther south, Hodes had set up a rear command post in a schoolhouse in Hudong-ni village, where the 32nd Tank Company along with 275 headquarters and supply personnel would spend the night. Late in the day, MacLean ordered the 31st’s Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon to scout the enemy’s positions. The platoon was ambushed in the hills east of Faith’s position by CCF troops and every member was either killed or wounded.

With the temperature nearing 30 degrees below zero on the night of November 27, 80,000 Chinese soldiers attacked X Corps along a 35-mile stretch of road east and west of the Chosin Reservoir. At 10 pm, reinforced by an additional infantry battalion from the 81st Division, 80th Division launched its surprise attack upon two of Task Force MacLean’s positions: the forward position of Faith’s battalion and the Pungyuri Inlet position two miles farther south. Blowing whistles, bugles, and horns and shooting flares, they hit Faith’s 1/32 along the north side of its perimeter. Airstrikes called in by Stamford and the men of 1/32 together inflicted heavy casualties upon the CCF attackers, but the battalion suffered more than 100 casualties. Two miles south, the situation was similar. The CCF struck 3/31 Infantry and two batteries of the 57th Field Artillery, overrunning much of the perimeter and killing or wounding most of the senior officers and noncommissioned officers. The 31st’s medical company was wiped out as well. Confused fighting went on through the night, with the Chinese withdrawing at dawn for fear of American air attacks. The 3/31 and artillery personnel suffered heavy casualties and one antiaircraft vehicle was destroyed.

Hodes’ rear command post at Hudong-ni was not attacked and he awoke early on November 28 to the sound of heavy gunfire to the north. Aware something had gone terribly wrong, he ordered Captain Robert Drake to push north with his 31st Tank Company toward the 3/31 and 1/32 perimeters. Drake set off with 16 tanks, with Hodes following in a jeep, and soon ran into trouble with the terrain. The ground was icy in some places, causing tanks to skid out of control, but was mushy in other areas, causing tanks to become mired. CCF troops attacked the tank column with American-made 3.5-inch bazookas, knocking out two; two others became hopelessly mired and were abandoned. With no air or infantry support, Drake called off the advance and he, Hodes, and the 12 remaining tanks withdrew to Sudong-ni. Upon arrival, Hodes borrowed a tank and rode to Hagaru-ri, ostensibly to seek help. He never returned to Hudong-ni.

Later that day, Almond flew into the 1/32 perimeter to confer with MacLean and Faith. Seemingly unaware of the crisis at hand, and although he had canceled any further Marine attempts to advance, he announced that Task Force MacLean would press on with the attack the next day after the expected arrival of 2/31. When Faith tried to inform Almond in detail of the previous night’s assault by elements of two enemy divisions, Almond said, “That’s impossible. There aren’t two Chinese divisions in the whole of North Korea! The enemy who is delaying you for the moment is nothing more than remnants of Chinese divisions fleeing north. We’re still attacking and we’re going all the way to the Yalu. Don’t let a bunch of Chinese laundrymen stop you.” Although Task Force MacLean was weak and vulnerable, especially after the previous night’s casualties, MacLean did not object to Almond’s order and was later much criticized for it.

At midnight on November 28 the CCF 80th Division attacked Task Force MacLean once again. The fighting inside both perimeters—1/32 and 3/31—was savage and hand to hand. At 2 am MacLean, still with Faith inside the 1/32 perimeter, ordered the battalion to withdraw south in the darkness to 3/31’s perimeter in a temporary measure to consolidate forces. Once 2/31 arrived the next day, MacLean fully expected to attack north as Almond had ordered. At dawn, however, when the 1/32 column reached high ground overlooking 3/31’s perimeter, MacLean and Faith were stunned to find the perimeter under heavy attack. One of Faith’s men later recalled it as a “scene of total devastation. In the confusion, while Faith and MacLean were fighting their way forward, MacLean mistook a column of CCF troops coming up from the south to be his overdue 2/31. When the Americans inside the perimeter began firing on the advancing column, MacLean ran forward onto the ice of the Pungyuri Inlet to stop what he thought was friendly fire and was shot several times by CCF troops. He was captured and died of his wounds four days later en route to a prisoner of war camp. He was the highest-ranking officer to lose his life in the Korean War.

Faith and his men finally fought their way into 3/31’s perimeter, only to encounter a ghastly mess. Hundreds of American, Chinese, and Korean dead littered the frozen ground. The 3/31 had suffered 300 casualties and its L Company had been wiped out. In MacLean’s absence, Faith assumed command of the consolidated forces; after search parties failed to find MacLean, the task force became Task Force Faith. That morning, Drake’s 31st Tank Company made another attempt to reach the task force perimeter only to be driven back to Hudong-ni by CCF troops dug in on Hill 1221. For the rest of the day, the newly designated Task Force Faith remained in position, saddled with almost 500 casualties and in no position to carry out any attack as ordered by Almond. Marine close air support and an airdrop of supplies helped matters somewhat, although the drop lacked 40mm and .50 caliber ammunition. Still without radio communication with the 7th Infantry Division headquarters or the Marines at Hagaru-ri, Task Force Faith’s position remained desperate.

Faith’s exhausted troops got a respite on the night of November 29. Chinese probing attacks and attempts to infiltrate the Pungyuri Inlet perimeter continued throughout the night but no general, coordinated attacks were launched. The CCF may have been pillaging Faith’s abandoned perimeter and may have been waiting for reinforcements. Barr flew in by helicopter to give Faith plenty of bad news: all X Corps units, including Task Force Faith, were now under the operational control of the Marines and were to withdraw. The Marines could supply Faith with air support, but other than that they would have to fight their way back to Hagaru-ri on their own. The 2/31 would not arrive. To make Task Force Faith’s situation even more desperate, the 31st CP, the 31st Tank Company, and the headquarters battery of 57th Field Artillery Battalion, approximately 275 soldiers, had all been ordered to evacuate to the Marine perimeter at Hagaru-ri, further isolating Task Force Faith. Not long after the task force’s sister units at Sudong-ni left for Hagaru-ri, the area was crawling with Chinese soldiers from the 80th and 81st Divisions, blocking Faith’s breakout route to Hagaru-ri.

The CCF 80th Division attacked at 8 pm, the fighting escalating as the night wore on. One task force survivor later stated he believed the enemy had been ordered to take the perimeter at any cost. Faith’s force suffered another hundred casualties during the night, bringing the number of wounded to almost 600. That morning, convinced the task force could not survive another major Chinese attack, Faith decided to make a break for Hagaru-ri and instructed his subordinates to prepare to move out at noon or shortly after, depending on when air cover arrived. The promised airdrop of badly needed ammunition for the antiaircraft weapons that might have saved the task force never materialized, diverted instead to two Marine battalions fighting on the other side of the Chosin. The breakout column’s heavy weapons teams remained critically short of ammunition; during the previous night’s attacks, the quad .50-caliber machine gunners had been forced to use only two of their four barrels in an effort to save ammunition.

The first Marine aircraft, which would stay with the column until nightfall, arrived at 1 pm, and Faith’s column prepared to exit the perimeter. Thirty two-and-a-half-ton trucks were carrying 600 wounded; due to acute ammunition shortages, Faith’s column included only four of the eight antiaircraft artillery vehicles, one 40mm gun each at the front and rear of the column and two .50-caliber machine guns in the middle. Chinese soldiers stood boldly in the open not far from the perimeter, watching the exhausted Americans prepare for the move south. As the vehicle column formed up on the road, the Chinese began moving down from the slopes, taking up positions along the breakout route.

Faith’s column finally moved out at 1 pm only to come under fire soon after exiting the perimeter. Chinese riflemen were shockingly close. As Stamford directed airstrikes for Marine Corsairs overhead, the lead plane dropped a napalm canister a millisecond too early. It landed just to the front of the column, striking the ground in a billowing gush of flame that engulfed a dozen Americans and sowed panic within the column. Until the napalm incident, the platoons and companies had maintained a semblance of their organizational structure, but now several units disintegrated into leaderless clusters of men, some of them flooding down the road in a mob, out of tactical control. Faith rushed forward, his .45-caliber pistol drawn, and managed to restore order.

The column moved on in fits and starts, the Corsairs swooping down to drive the Chinese away from the road. Several pilots overhead reported massive concentrations of enemy troops all along and around the breakout route. As the Chinese poured in fire from the high ground, taking a dreadful toll upon the task force’s drivers and wounded, the column was forced to halt at a destroyed bridge. The tracked antiaircraft vehicles were able to bypass the barricade, but only one wheeled truck could be winched across a dry streambed and up the steep slope on the other side, a grueling two-hour task. It was already nearing dusk when the last truck was winched over the frozen marsh.

Wounded men in the trucks were now being wounded again or killed outright, and truck drivers were heavily targeted as well. Under heavy fire, many members of the rear guard sought shelter in a ditch below the road rather than protect the trucks. Some even headed for the reservoir, hoping to move across it to the safety of Marine lines. “Toward dusk I looked toward the end of the column and saw Chinese closing in on the rear, and there were already some GIs walking up to them with their hands above their heads,” said Sergeant Chester Bair afterwards.

The column finally began moving again, only to be stopped a short distance to the south by a Chinese roadblock at the base of Hill 1221. The hill was within range of some of the tank guns and artillery now at Hagaru-ri, and Faith’s column would have profited from artillery support, but it wasn’t forthcoming. Two groups of brave soldiers, led by wounded officers, stormed Hill 1221 and cleared most of it despite suffering severe casualties. It was getting dark and the lights of Hagaru-ri could be seen across the frozen reservoir. Many of the men who stormed the hill, unfortunately, rather than returning to the convoy, continued out onto the frozen reservoir and headed for the Marine perimeter at Hagaru-ri.

Faith got the convoy moving again only to hit yet another roadblock after rounding a hairpin turn. Gathering a small force of able-bodied volunteers, he charged the roadblock and cleared the area of enemy soldiers. Faith, though, was critically wounded by the fragments of a Chinese grenade. His men managed to prop him up on the hood of his jeep, and the column began moving slowly forward once again. Despite the heroic efforts and the few remaining officers, the task force began to come apart. The column managed to creep forward in the dark but was finally halted for good by another Chinese roadblock just north of Hudong-ni village. The Chinese intensified their attacks, throwing white phosphorous grenades into stalled vehicles loaded with wounded, setting some of them on fire. Faith, hit again by rifle fire, died of his wounds. He received the Medal of Honor posthumously. At about 10 pm, in total darkness, Task Force Faith ceased to exist. Those who could escape ventured out onto the ice and began the arduous march to the Marine lines.

Behind the men escaping across the ice lay a long line of destroyed trucks. During the night of December 1, the shattered remnants of Task Force Faith trickled into Hagaru-ri, and by dawn 670 soldiers had been taken to the hospital or warming tents. Many came through a sector held by the Marine 1st Tractor Battalion. The unit’s commander, Lt. Col. Olin Beall, led rescue missions across the ice in a jeep, picking up more than 300 survivors, many suffering from wounds, frostbite, and shock. Of the 1,050 survivors that reached the Marine lines, only 385 of them were considered able bodied. The survivors, along with other 7th Infantry Division troops, were organized into a provisional battalion that numbered 500 and attached to the 7th Marine Regiment. Known as 31/7, the battalion participated in the 1st Marine Division’s breakout from Hagaru-ri to the coast beginning on December 6. More than a thousand members of the task force were killed or died in Chinese captivity, almost a third of the task force’s original strength.

When the Korean War ground to a halt with inconclusive results, Task Force Faith was ignored and forgotten, one of the war’s many unfortunate and regrettable actions. Therefore, the presence and fate of Army troops east of Chosin in November and December of 1950 is not well known. Many accounts of the Chosin campaign tend to overlook or minimize the Army’s role there, or even suggest that the task force disgraced itself. Also overlooked is that Task Force Faith accomplished at least part of its mission: it successfully guarded the right flank of the also surrounded 1st Marine Division, protecting it from additional Chinese attacks for four full days. If not for the presence of the Army task force, the CCF 80th and 81st Divisions might have captured the key Marine base and airstrip at Hagaru-ri before the Marines had concentrated sufficient units to defend it.

Such an event would have blocked the only escape route of the Marines and other Army units. A number of historians, and some Marine veterans of the campaign, now believe the 1st Marine Division might have been destroyed had the understrength soldiers of Task Force Faith not bought time by keeping the Chinese from sweeping south. Recently released Chinese documents show that Task Force Faith fought a significantly larger enemy force than previously believed. Despite heavy losses, X Corps preserved much of its strength and Smith was rightly credited with saving his division from annihilation.

The CCF’s “victory” came at a staggering cost. Chairman Mao’s mission of annihilating X Corps, and especially the 1st Marine Division, never materialized. The effects of combat, severe cold, and poor logistical support wreaked havoc within the divisions that attacked X Corps. The Chinese soldiers alsosuffered from the lack of winter clothing due to Mao’s haste to get them deployed to the reservoir area. The 80th Division that attacked Task Force Faith was virtually destroyed. Not until March 1951 did the CCF Ninth Army Group return to its normal strength and become combat effective once more. With the absence of nearly 40 percent of CCF forces in North Korea in early 1951, U.N. forces were able to maintain their foothold on the Korean peninsula.

After the war, a U.S. Navy chaplain wrote a report denigrating the performance of Task Force Faith. He went so far as to suggest possible cowardice and dereliction of duty. Smith continued to insist, until the day he died, that “the U.S. Army forces made no contribution whatsoever to the withdrawal of the 1st Marine Division.” For 50 years, the Navy Department refused to support the awarding of a Presidential Unit Citation to the U.S. Army’s units east of Chosin, though it awarded one to the 1st Marine Division in 1952. The task force’s records remained in the National Archives. The U.S. government declassified the records in 1979 when service members and historians began to reevaluate the battle. Historians now believe that the men of Task Force MacLean/Faith fought bravely and performed well given the dire circumstances. The task force ultimately received the Presidential Unit Citation in 2001.

Lieutenant Colonel Faith’s remains lay for decades in an unmarked grave in North Korea. They eventually were recovered and positively identified in October 2012 nearly 62 years after the battle. He was buried with full honors in April 2013 at Arlington National Cemetery.

My great aunt, Mamie Smith Dew, lost her son on Nov 30 1950. He was x Corp. I have searched and read for years about him. He went missing, and only presumed dead years later. Aunt Mamie lived to 96 years old and died around 2004(?). This is the BEST article I have read in all of the information I have found. I did obtain a muster roster from Nov 30 years ago (1999). There were 4 still living and I contacted the 3 I could find. He said to me, “how the h*** did you get a muster roster? That was the day hell came to earth. So many Chinese soldiers that they blocked the sun.” Thank you for this step by step up to the day after he went missing. My aunt said he, Daniel Edward Banks, cashed a check at Hagaruri. Never did understand that.

I hope it helped…..John W.

My uncle , MSGT Charles Ogden was killed while a member of the 7th infantry and died in Dec., 1950. We have no knowledge of how or where in the Chosin he was when it happened. Would anyone with any knowledge of him please e-mail me. He was also a surviving member of Merrill’s Marauders in WWII . I am a namesake and would love any additional information. Thank you in advance.

Your Uncle was killed Dec 1, 1950. He was first reported as MIA and then later reported as KIA. Please email me for further details

Julee

Towards the end of his life, Harry Truman was asked whether the decision to drop the atomic bombs in 1945 had been a difficult one.

He replied, “The atom bomb? A difficult decision? No, I made it like THAT” and snapped his fingers before continuing, “No, the atom bomb wasn’t the difficult decision of my Presidency. The difficult decision was Korea.”

If you are interested in the Chosin Reservoir battles you should read Hampton Sides book, “On Desperate Ground”. It is well written and comprehensive book about this battle. He pulls no punches when it comes to his evaluation of Generals MacArthur and Edward Almond. Their arrogance proved to be very costly.

This was a very vicious battle and the Americans escaped because of the-30 degrees temperature. Task force faith the 31st regimental combat team, had sustained slightly more casualties then the 1st Marine Division. Thank goodness that they had the Army Engineers who were able to construct a Treadway bridge across the blown-up bridge at The Fuclin pass. I must recommend the book East of chosen written by Applegate. They also should recommend that you stop by the cemetery where the Navy chaplain who accused the army of cowardice has buried 2 micturate on his grave.