By John Brown

When World War II began in September 1939, just nine months before the Siege of Malta, its three small islands in the central Mediterranean were still considered part of the British Commonwealth. Soon, Malta’s geographical position would prove to be one of the most decisive factors of the war in the Mediterranean. It lay 985 miles from the British base at Gibraltar and 820 miles from the base at Alexandria, astride Britain’s sealanes to Egypt and the Middle East and through the Suez Canal to India, Asia, and Australia. From Malta’s harbors it was possible for the entire Mediterranean to be dominated by warships and submarines, and from its three airfields and seaplane base by fighters, bombers, torpedo, and reconnaissance aircraft.

In June 1940, Mussolini’s Italy allied itself with Hitler’s Germany and declared war on Britain and Malta, 95 square miles in extent, smaller than London, found itself surrounded by enemy territory and bases. Sicily was only 60 miles to the north, and Italian-ruled Libya 180 miles to the south. Italy’s navy and air force were large, modern, and strategically placed at bases on Sicily, Sardinia, Pantellaria, and the Dodecanese group of islands. A week after Italy’s declaration of war, France’s Marshal Petain ordered the French to stop fighting and sued for peace. Malta was left threatened by a potential German takeover of the powerful French fleet and its bases in the Mediterranean and North Africa. (Subscribe to WWII History magazine to get a more in-depth look at the North Africa campaign.)

Often Outgunned by the Italian War Machine

Malta’s air defense consisted of 42 antiaircraft guns, five antiquated Fairey Swordfish torpedo planes of the Fleet Air Arm, a Queen Bee target drone, and four Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters. Early on the day after Italy’s declaration of war, 25 Savoia Marchetti SM-79 bombers of the Regia Aeronautica, escorted by 12 Macchi C.200 fighters, came in from Sicily to bomb the Maltese capital of Valletta and the installations around Grand Harbor. The four Gladiators went up to intercept them, and the Siege of Malta had begun.

The Gladiators, older and slower than the Italian planes, were able only to slightly damage one of the bombers before they flew away, leaving smoking ruins behind them. The Italians came back in increasing numbers, six times in the next nine days, and the Gladiators failed to shoot down any of them. Then, on June 22 an SM-79 on reconnaissance was intercepted and shot down by a Gladiator. During the same week, two more bombers were shot down. One Gladiator was so badly damaged in the actions it had to be written off, leaving the remaining three to be nicknamed “Faith, Hope and Charity.”

Daily Air Raids

Air raids continued every day, but on June 28 four Hawker Hurricane fighters were flown to Malta from North Africa to reinforce the Gladiators, with 12 additional Swordfish torpedo planes intended to attack Italian shipping. With their arrival, air raids became less frequent. When more Hurricanes were ferried to Malta by aircraft carrier in August there were enough to form a squadron. Other aircraft filtered in to create a small strike force consisting of the 12 Swordfish torpedo aircraft and a few Vickers-Armstrong Wellington bombers and Short Sunderland flying boats.

Malta was not self-supporting. There was no way it could survive without outside help, and this meant convoys of ships bringing in food for the 250,000 Maltese and the British garrison along with oil and military supplies of all kinds.

To end the threat of the French fleet being used by the Germans against convoys for Malta, the British navy sent some of its warships to Oran and Mers-el-Kebir in Vichy-French occupied Algeria to negotiate the future of French naval forces. When the French refused to negotiate, a number of their ships were sunk and damaged, and French naval forces at other ports were disarmed. Convoys from the eastern and western ends of the Mediterranean could now supply Malta more freely, easing the pressure on British submarines that had been bringing in essential military personnel, urgent stores, and oil. During September, two heavily escorted convoys docked in Grand Harbor with aviation fuel, ammunition, and food.

Taranto: Precursor to Pearl Harbor

In November, reconnaissance aircraft from Malta photographed a large portion of the powerful Italian fleet anchored at the naval base at Taranto. Using the photos obtained by the reconnaissance pilots, planes from the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious disabled three battleships, two cruisers, and several other ships, bombed the seaplane base, and started fires in an oil storage depot. The raid crippled the Italian fleet and made Mussolini reluctant to risk a direct confrontation with the British Royal Navy, lessening the threat against Malta.

In December, Malta-based reconnaissance planes discovered a force of 350 Luftwaffe bombers and fighters based in Sicily. In early January 1941, some of the German bombers attacked the Illustrious, but battered, smoking, and listing badly she managed to limp into Valletta’s Grand Harbor.

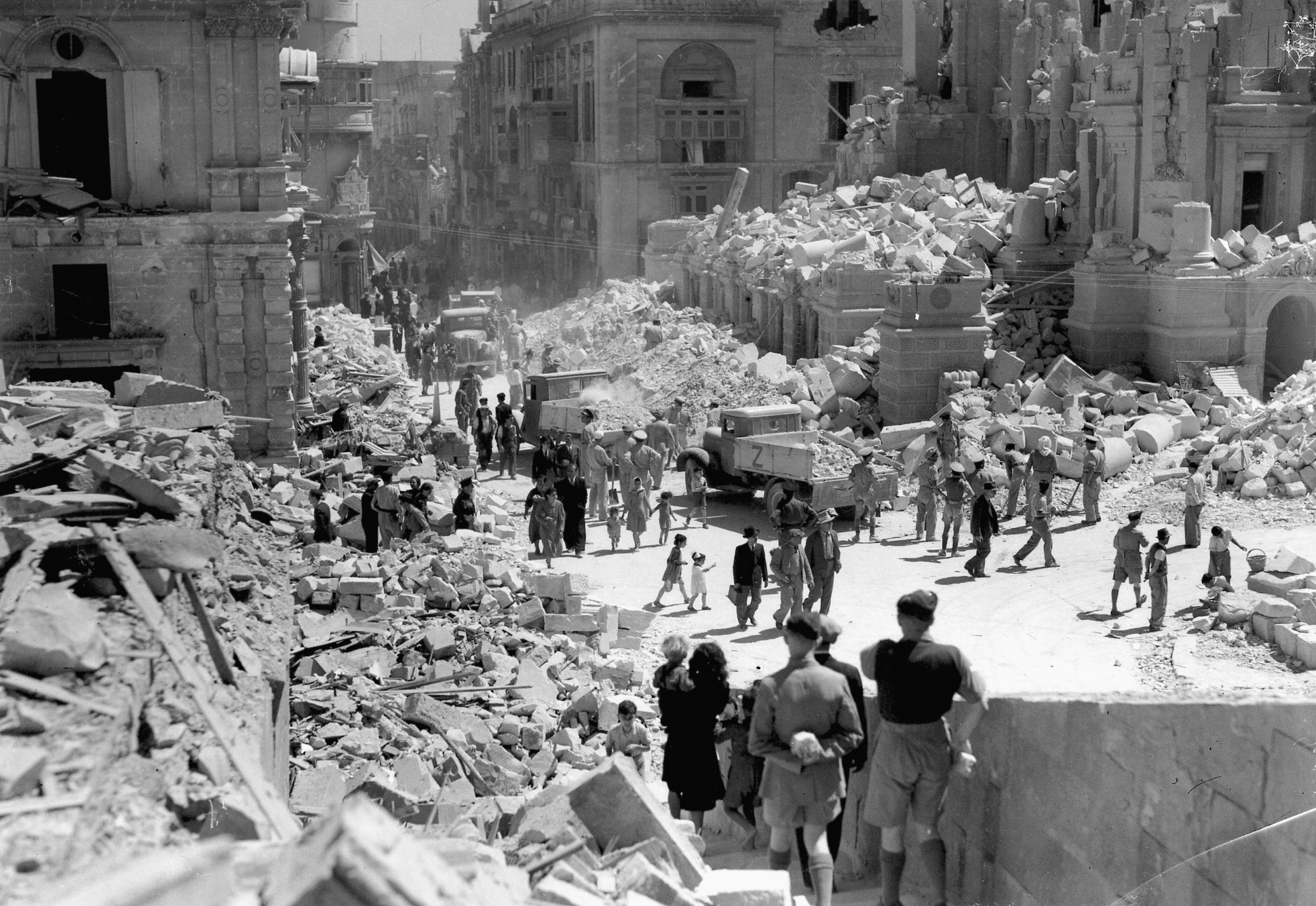

On January 16 more than 70 German Junkers Ju-88 twin-engined medium bombers and Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers, escorted by Italian CR42 fighters, attacked Valletta. Three Fulmars and four Hurricanes, the only serviceable British planes at the time, and an antiaircraft barrage from the shore and ships in the harbor, met them. The Italian fighters held off the British planes while the Junkers bombed the city and installations, leaving smoking ruins behind. Luckily, the Illustrious survived the bombing and, repaired, sailed out of Grand Harbor a week later.

Rommel Arrives in Tripoli

In February, German armor under the command of General Erwin Rommel, later to gain fame in North Africa as the Desert Fox, arrived in Tripoli to reinforce the Italians and stabilize the Axis position in Libya as both Germany and Italy began to massively reinforce their North African front. Malta was astride their supply routes across the Mediterranean, a constant danger to their shipping, so the British bastion had to be neutralized. In addition to stepping up the bombing of Malta’s airfields, dockyards, and other military targets, the Luftwaffe dropped parachute mines at night into the approaches to Grand Harbor and other anchorages. These sank and damaged a number of British ships, but in the first four months of 1941 submarines from Malta, avoiding the mines, sank 25 Axis supply ships bound for North Africa.

At the end of May, the Luftwaffe was withdrawn from Sicily to support the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa. The following month, Malta was reinforced with a squadron of Bristol Blenheim twin-engined bombers, tasked to sink Axis ships carrying supplies for Rommel’s forces.

“The sinking of any one ship,” Air Vice Marshal Hugh Lloyd, commander of the Royal Air Force on Malta, wrote later, “might have meant the loss to the enemy in the desert of at least ten tanks, two or three batteries of artillery, one hundred motor vehicles, perhaps sufficient spares for one hundred or more aeroplanes, food for a month for one hundred thousand men and ammunition for one hundred guns for a battle.” Between May and October, planes from Malta sank nearly 100,000 tons of Axis shipping.

In July, a convoy of six merchant ships under strong Royal Navy escort sailed from Gibraltar for Malta and, despite continuous air and surface attack, reached Malta with only one merchantman damaged.

On the night of July 25, a group of Italian motorboats loaded with explosives and escorted by German E-boats (fast torpedo boats) arrived off Grand Harbor as dawn was breaking. However, they were detected, and as the motorboats entered the harbor they were met with a barrage of fire that destroyed all of them. Cannon-firing Hurricanes pursued the retreating E-boats, sinking several.

In September, another convoy got through to Malta, and in early November destroyers from Malta sank six Axis merchantmen off Libya. But then, in December, the Luftwaffe returned to the Mediterranean. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, commander of the German Navy, had had his way.

Raeder had been advocating an offensive in the Mediterranean that would take Axis forces from North Africa through the Middle East to link up with a German drive through the Ukraine. He stressed that to achieve this objective Malta must be taken. Hitler agreed with him and in November issued a directive that withdrew a complete Air Corps from Russia for use in the Mediterranean. He also appointed Field Marshal Albert Kesselring commander-in-chief of operations. His orders were to secure mastery of the air and sea in the central Mediterranean to allow free communication with North Africa, to keep Malta under bombardment, to help Axis forces in their drive on Egypt, and to close the Mediterranean to British shipping. He had 2,000 frontline aircraft to use in Sicily, Greece, and Crete.

Luftflotte (Air Group) II was based in Sicily. It numbered 325 aircraft, Ju-88s, Ju-87s, Heinkel torpedo bombers, Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters and Me-110 twin-engined fighter escorts and interceptors. It included units specially trained in anti-shipping tactics. Massive attacks on Malta began, sharply reducing RAF anti-shipping missions and allowing better resupply of Rommel’s forces. The Desert Fox counterattacked in Libya, and, with Libya’s airfields in Axis hands, convoys from Alexandria to Malta had to run the gauntlet of “Bomb Alley” between Crete and Cyrenaica.

In February 1942, three modern, fast merchant ships with an escort of eight Royal Navy warships, reinforced by six warships from Malta, tried to dash through Bomb Alley. None of the merchant ships made it. In March, it was tried again, this time with diversions to draw off attacks, and three out of four merchant ships, one badly damaged, got through to Malta. For two days and nights servicemen and civilians worked to unload their cargoes under sustained Luftwaffe attack, but the three freighters were sunk with only 5,000 tons of supplies saved. The German onslaught continued with such ferocity that the Royal Navy had to withdraw its surface ships from Malta or lose them. The same happened with the Wellington and Blenheim bombers; they were flown to safety in Egypt.

Toward the end of March, the RAF commander on Malta advised London, “ … The Battle of Britain is nothing compared with this, certainly as regards being outnumbered and in having no reserves whatsoever.” On April 1, the Governor General of Malta, Lord Gort, warned the British government of “a dangerous shortage of flour, fodder, oil, coal, and ammunition.” That month Malta averaged an air raid every two and a half hours with 7,000 tons of bombs falling on the island, killing 300 civilians and destroying or badly damaging 10,000 buildings. With the bombers came the Me-109s to hover over the bomb-cratered airfields and swoop down to attack when an RAF plane landed to refuel and rearm.

The Maltese people, always hungry, lived below ground in Malta’s many natural catacombs and caves or in air raid shelters blasted from the rock. A soldier noted, “I’ve never seen people like the Maltese for stamina and fortitude. You would see them weep and wail, but immediately after they were marvellous. Everyone would come out after the raids to see if the neighbors were alright and then they would get on with their lives.”

On April 15, at the height of the bombing, Malta was awarded the George Cross, the civilian award equivalent to the military Victoria Cross. Britain’s King George VI made the award saying, “To honor her brave people I award the George Cross to the island fortress of Malta, to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history.”

On April 20, a contingent of 47 Supermarine Spitfire fighters arrived on Malta after being ferried by the U.S. aircraft carrier Wasp. Virtually out of fuel, they were caught on the ground by German dive bombers, and only 17 were left serviceable. During April, with bombing continuous all day and every day, 80 Spitfires and Hurricanes were lost and 48 damaged. Most of these were hit while trying to land to refuel and rearm. Despite the odds, nearly 200 Axis planes were shot down during the month. The British submarine flotilla, which the numerous air raids had forced to dive at their berths during the day, was withdrawn at the end of the month, and Malta ceased to be a naval base.

On May 9, another 62 Spitfires landed from the carriers HMS Eagle and Wasp, but this time refueling was worked out in detail and every serviceable plane was in the air again within 30 minutes of landing on the airstrips. A newly arrived pilot wrote: “The tempo of life here is indescribable. The morale of all is magnificent—pilots, ground crews, and army—but it is certainly tough. The bombing is continuous on and off all day.”

Another wrote: “One lives here only to destroy the Hun … living conditions, sleep, food, have gone by the board … It makes the Battle of Britain seem like child’s play.” The pilots and aircrews were a mix of British, Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders. Probably the most colorful of them was a Canadian, George “Screwball” Beurling; he shot down nine Axis bombers during his first week of operations on Malta, and in the following four months his tally rose to 29.

On May 10, a fast minesweeper, HMS Welshman, made a dash from Gibraltar and arrived safely in Grand Harbor with urgently needed food and ammunition. In June, two convoys, one from Gibraltar and the other from Alexandria, left simultaneously for Malta. The one from Gibraltar was attacked from the air and by Italian warships. Only two of the freighters reached Malta with 15,000 tons of supplies. Torpedo-carrying aircraft and E-boats attacked the convoy from Alexandria, and then, confronted by a fleet of Italian warships, it turned back to Alexandria.

In early July, Rommel’s North African advance was halted at El Alamein just 150 miles from Cairo, and Field Marshal Kesselring, believing that Malta was the key to Rommel’s supply problems, called in 600 planes to begin a final assault that would obliterate Malta as a base. But Malta’s fighter force had been strengthened, and 100 Spitfires went up against the Axis air fleet. The assault lasted two weeks until, with 50 Axis bombers and fighters shot down, Kesselring called off the assault. RAF torpedo planes returned to Malta to resume daylight attacks on Rommel’s supply ships, and Wellington bombers adapted to carry torpedoes attacked them at night.

Two tankers crossing the Mediterranean with oil for Rommel’s tanks and vehicles were sunk, and Rommel, desperate for oil for the battle which he knew was coming at El Alamein, appealed for more. A tanker carrying 5,000 tons of oil, the San Andrea, left Italy at once escorted by two destroyers and German and Italian aircraft. An RAF reconnaissance plane from Malta spotted the tanker and radioed back its course and speed.

RAF Squadron Leader Pat Gibbs led nine Beaufort torpedo bombers and nine Beaufighters over the Italian mainland then swung around to come in behind the high priority target and its escort. The Beaufighters shot a passage through the air escort for the Beauforts, and the torpedo bombers, led by Gibbs, dived through. Gibbs dropped his torpedo at 500 yards, and as he pulled out of his dive the San Andrea exploded in a ball of flame and smoke. Deprived of his fuel, Rommel had to call off an offensive that had already begun at El Alamein.

Despite this reversal of fortune, Malta was starving.

At the beginning of August, Lord Gort advised London that by September 7 Malta would have to surrender due to starvation and lack of military supplies. A major convoy was quickly organized; it was codenamed Pedestal.

In Britain, 14 merchant ships were filled to capacity with food, ammunition, and other supplies. Together with the huge, American-built tanker Ohio, filled with 11,500 tons of kerosene, petrol, and aviation fuel, they sailed for Gibraltar. There, a covering escort met them; it was commanded by Vice Admiral E.N. Syfret and comprised of the battleships Nelson and Rodney, the aircraft carriers Eagle, Indomitable, and Victorious (together carrying 73 aircraft), three cruisers, and 14 destroyers. There was also a close escort, commanded by Rear Admiral H.M. Burrough, comprised of three cruisers, one antiaircraft cruiser, and 11 destroyers.

In the Mediterranean, two submarines patrolled north of Sicily and six more south of Pantelleria where the Sicilian Narrows would be a particular threat to the convoy. Another aircraft carrier, HMS Furious, was 600 miles east of Gibraltar on its way to deliver 38 Spitfires to Malta.

Impressive as the escort was, the danger to the convoy was just as impressive. Along the North African coast, Algeria and Tunisia were in Vichy-French (pro-German) hands with whatever dangers could emanate from there. However, the greatest danger was the 540 Axis aircraft on Sicily, Sardinia, and Pantelleria together with 23 German and Italian E-boats and 21 submarines. Behind them lurked the Italian fleet with its formidable collection of battleships and heavy cruisers.

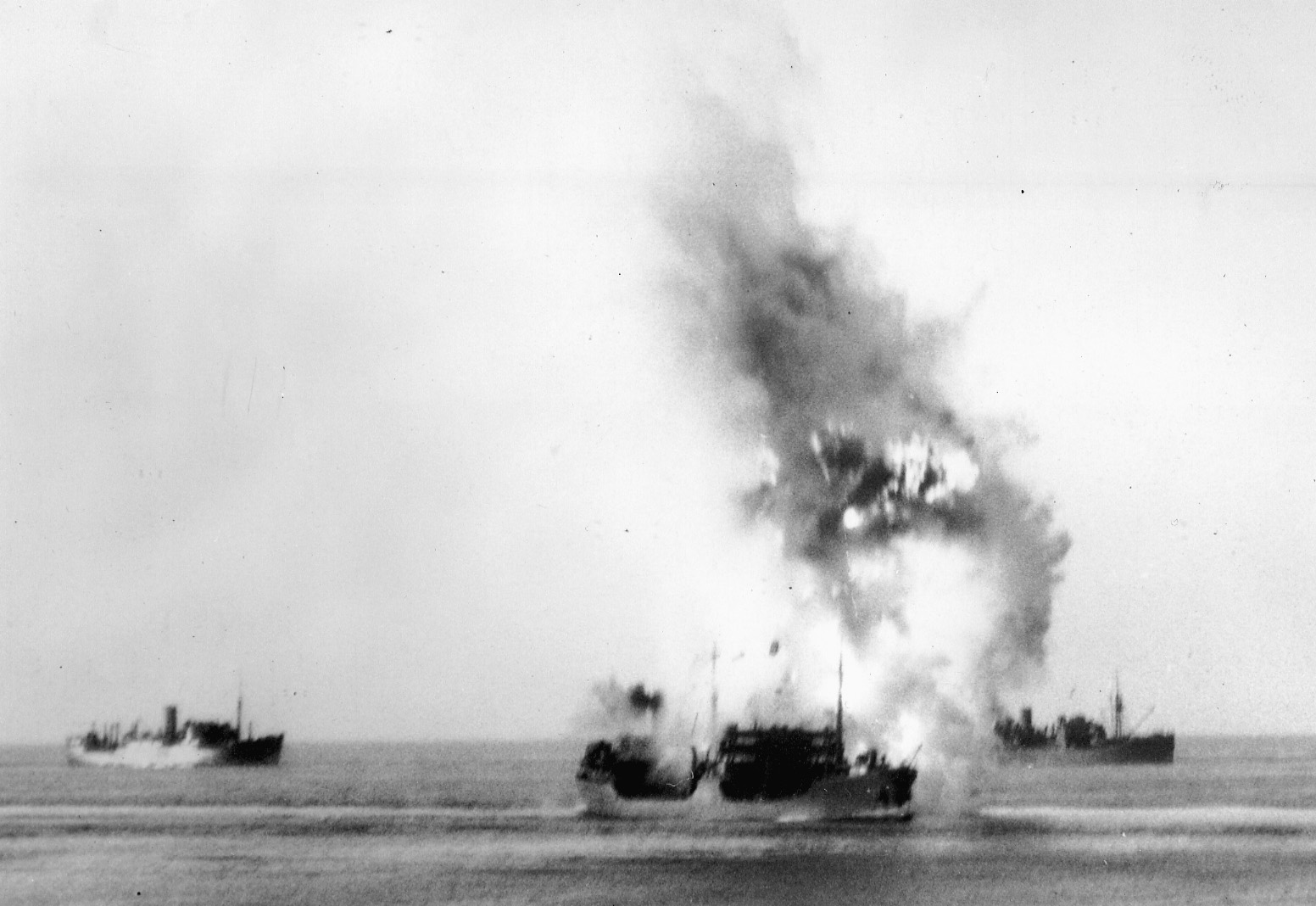

The convoy left Gibraltar on the morning of August 11, and by lunchtime had suffered its first casualty when the German submarine U-73 penetrated the protective destroyer screen and put four torpedos into the Eagle. The carrier turned on her side, sliding her aircraft into the sea. She went down, but 900 of her crew were saved.

Thirty-six Luftwaffe bombers attacked in the last light of day, but they were driven off by antiaircraft fire and the night was peaceful for the convoy as RAF bombers pounded Axis airfields.

The following day, Axis bombers and fighters came back over the convoy at noon. The carrier Victorious was hit, though not seriously, and one of the merchant ships was severely damaged and later sank. During the afternoon enemy submarines were detected but evasive action saved the convoy. One of the submarines, an Italian, was brought to the surface by depth charges and rammed and sunk by a destroyer. The destroyer, its bow crushed, made its way back to Gibraltar.

That evening, near Cape Bon, Tunisia, Stuka dive bombers and Savoia Marchetti torpedo bombers struck, sinking a destroyer and damaging the Indomitable’s flight deck so badly it was unusable. At nightfall five Axis submarines and 19 motor torpedo boats struck the convoy, torpedoing a cruiser and so badly damaging it that it had to return to Gibraltar. The antiaircraft cruiser was torpedoed and hopelessly damaged; it was sunk by British gunfire. The tanker Ohio had a hole 27 feet by 24 feet blown in her port side by a torpedo. The kerosene tanks were set on fire, but the rushing sea helped control the fire and she kept going. An attack by 20 Ju-88s sank two merchantmen, and at the same time another cruiser and merchantman were damaged by torpedoes.

The Pedestal convoy rounded Cape Bon at midnight, and 10 E-boats struck. A cruiser was crippled by torpedoes and scuttled by her crew, two merchantmen were sunk, and two others so badly damaged their crews had to abandon them. By dawn on the 13th, less than half the merchantmen remained, but the vital tanker Ohio, terribly battered, with her deck split across the center and in danger of breaking in half, kept going. The beleaguered convoy was now a mere 100 miles from Malta.

An hour later, the German bombers and dive bombers were back, sinking a destroyer and setting fire to a merchantman that completely burned. The Ohio was damaged again when a bullet riddled Ju-88 crashed into her forecastle and a Ju-87 onto her poop deck. Incredibly, she survived, but her engines gave up and she was left behind. The three remaining merchantmen, protected by two cruisers (one of them damaged) and seven destroyers, raced for Malta.

The prior evening, a reconnaissance plane from Malta had detected two Italian cruiser squadrons northwest of Ustica, presumably preparing for a dawn attack on what was left of the convoy. The new air officer commanding Malta, Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, a New Zealander who had fought at Gallipoli during World War I and led 11 Fighter Group in the Battle of Britain, had no resources to attack the Italian squadrons.

Park sent a few Wellington bombers during the night to drop flares and bombs on and around the Italians to confuse them into thinking a more serious threat awaited them. Before dawn on the 13th, he sent messages to the Wellingtons referring to large Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers and cruisers approaching the Italian squadrons. It was a fiction, there were no Liberators or cruisers, but the Italian commander picked up the messages and ordered the cruisers back to port. A British submarine torpedoed and so severely damaged two of the Italian cruisers that they were never used again.

Air attacks on the Pedestal convoy petered out as it came within range of Spitfires and Beaufighters from Malta. From then on, 16 Spitfires kept constant patrol over the Ohio, during which they shot down several Ju-87s and Italian fighters. At 6 pm on the 13th, the three remaining merchantmen of the convoy reached Grand Harbor to the great relief of cheering crowds on shore. Later, another merchantman made its way in with 10 feet of water in its No. 1 hold. The food these ships delivered would stave off starvation, at least for a while, and the ammunition would keep the island’s guns firing.

While the crowds cheered, 70 miles away the tanker Ohio was still fighting for her life. Throughout the day she had fought off repeated air attacks, helped by the guns of the destroyer that stood by her. Two bombs had fallen so close to her that they exploded under her hull, lifting her out of the water. Riding dangerously low in the water and almost impossible to steer, the tanker was taken in tow by a minesweeper. Then, a tandem tow was attempted with the destroyer, but both failed.

After more damage from air attack, the crew abandoned the Ohio. However, sailors from the destroyer boarded her and kept her afloat during the night. When dawn broke the captain and crew returned to their ship. Another destroyer turned up to help, and more minesweepers were on the way from Malta when the Germans made another desperate attempt to finish off the Ohio. Five Stukas escorted by fighters attacked. One of the Stukas dived through the covering Spitfires and dropped a 1,000-pound bomb in the Ohio’s wake, so close its explosion propelled the ship forward, twisting her screws and holing her stern.

By afternoon, two of the destroyers had secured themselves on either side of the Ohio, holding her up while the third destroyer sailed around them dropping depth charges to discourage U-boats. By dawn the next day, August 15, with Malta a smudge on the horizon, two tugs appeared. One attached itself to the bow of the Ohio, the other to the stern, and supported by the tugs and the destroyers she was brought into Grand Harbor. The massed crowds cheered themselves hoarse. When the last gallon of oil was pumped from her, the gallant Ohio was towed to a quiet backwater of the harbor where she broke in half.

In terms of losses, the convoy battle was a victory for the Axis, but for the British it was a strategic success. The arrival in Grand Harbor of the four merchant ships and particularly the Ohio ensured that Malta would battle on; without the Ohio’s oil the defensive capability of the garrison would have come to a standstill. Within weeks Malta would have fallen.

In August, Malta’s planes and submarines destroyed 35 percent of the total Axis supplies intended for North Africa. In September, more than 100,000 tons of supplies for Rommel’s Afrika Korps were sent to the bottom of the Mediterranean, and the losses were even greater in October. Malta’s bombers, torpedo bombers, and submarines were so worrying the Axis that some of their ships would sail from Italian ports three or four times only to turn back when they spotted British reconnaissance planes.

The continued threat of attack from Malta forced Axis planners to begin routing convoys by way of Greece and the Corinth Canal and Crete, adding many days to their journeys. When General Bernard Montgomery launched a British offensive at El Alamein on October 23, the Afrika Korps was gravely short of supplies.

Air attacks on Malta became less fierce as Axis planes were diverted to help Rommel, but on October 11 the blitz resumed in an attempt to protect Axis shipping. For eight days the fighting was savage, 42 Axis planes were shot down for the loss of 27 RAF planes, and then the Germans and Italians had had enough. Daylight raids against the island were called off.

By mid-November there were only two weeks’ food left on the island. Four merchantmen, escorted by cruisers and destroyers, sailed from Alexandria and arrived in Grand Harbor without loss, signalling the end of Malta’s ordeal. The price paid for her part in the war was heavy—1,540 Maltese civilians killed and 1,846 wounded along with heavy losses among the military garrison and naval and merchant seamen. Approximately 700 planes were lost in the defense of Malta, along with dozens of ships.

After the war, an official Italian report stated, “Malta was the rock on which our hopes in the Mediterranean foundered.” If Malta had not held out, the Mediterranean would have become an Axis sea, giving the Germans and Italians free rein. The consequences of such an outcome are too serious to contemplate.

Author John Brown last contributed to WWII History with a story on the coastwatchers in the Pacific theater. He hails from Minyama, Queensland, Australia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments