By William E. Welsh

Rather than embrace his appointment to command the confederate forces in northwestern Virginia with enthusiasm, Brig. Gen. Robert S. Garnett expressed morbid dread.

“They have not given me an adequate force,” Garnett was overheard to say the day before he left Richmond for the battlefront in the Alleghenies. “I can do nothing. They have sent me to my death.”

At the time, Garnett was serving as adjutant general of Virginia’s volunteer army under Robert E. Lee. Garnett graduated from West Point in 1841 and served on the staff of Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor during the Mexican-American War. Having served in the U.S. 4th Artillery Regiment, he was well qualified to step forward and direct the crew of a 12-pounder at the Battle of Buena Vista when its commander was seriously wounded.

Tragedy stalked Garnett. While serving at Fort Simcoe in the Washington Territory his wife and only child, who resided with him at the fort, both died of fever in September 1858. “One day he went off on a mission,” wrote Mary Boykin Chestnut. “They were gone six weeks… when he came back, his wife and child were underground.”

In the wake of the Confederate defeat at Philippi on June 3, 1861, the Confederate government promoted Garnett to brigadier general and sent him off to stabilize the situation in the Tygart Valley. But Brig. Gen. George B. McClellan defeated part of his army at Rich Mountain. Garnett then led 3,500 Confederates at Laurel Hill on a retreat through rugged terrain with a Union force in hot pursuit.

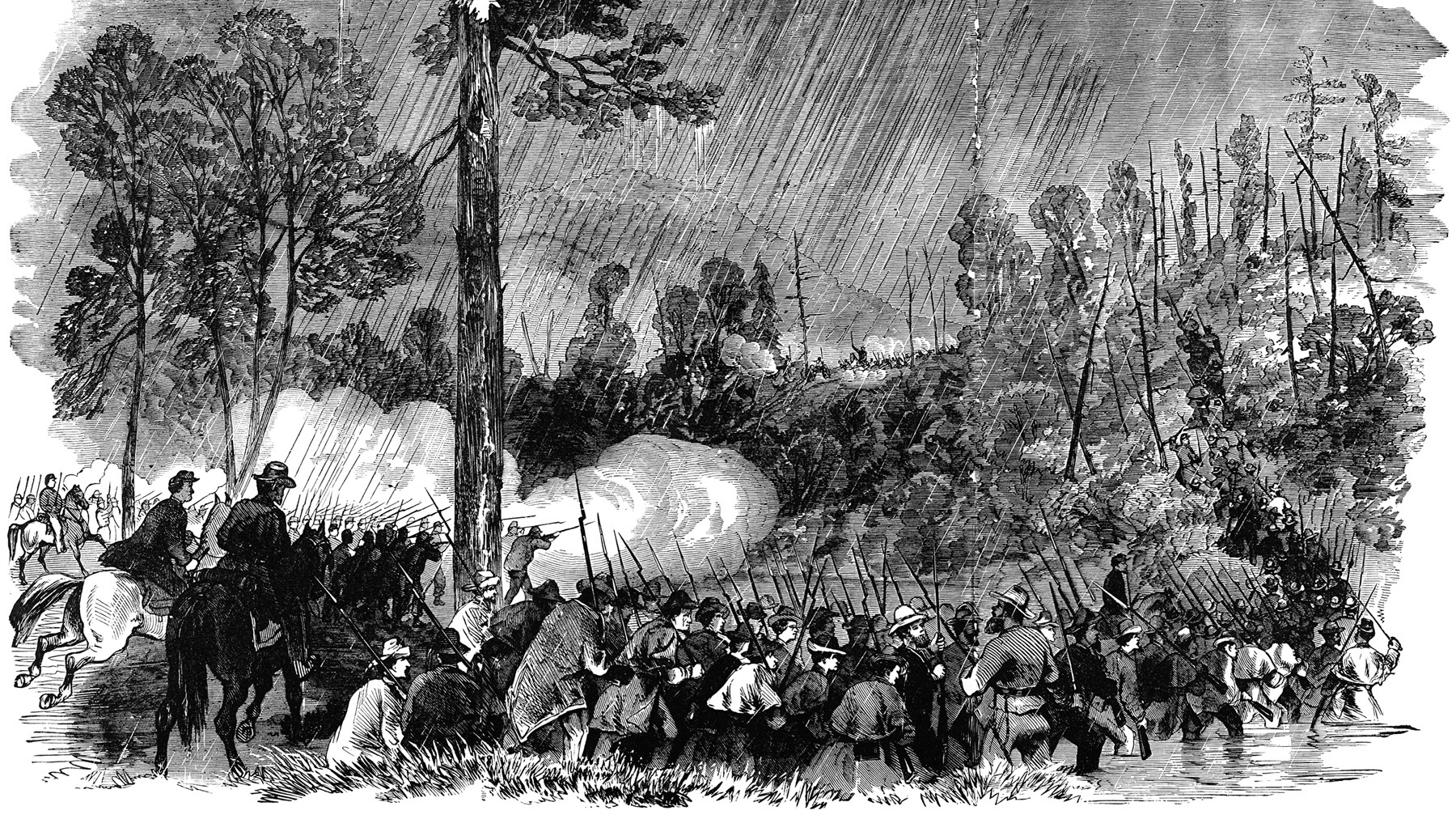

Garnett’s intention was to gain the Cheat Valley and from there make it to Staunton. Garnett refused to leave his wagons and artillery behind, and it slowed his column considerably. When the two-mile-long column reached Shaver’s Fork of the Cheat River, it found the tributary had risen considerably from the heavy rains. Garnett deployed the 23rd Virginia and 1st Georgia Regiments as a rear guard to protect his wagons. He planned to have one regiment pass through the other and reform in leapfrog fashion to keep the Yankees at bay.

The Federals struck on July 13. After the Confederates had forded the twisting river twice, a sharp action took place at Corrick’s Ford where Confederate wagons had a difficult time crossing through the swift-flowing water. Three rebel guns atop an 80-foot ridge banged away at the Federals. Colonel William B. Taliaferro’s 23rd Vigrinia beat back two Federal assaults in a 30-minute clash in which the Virginians suffered 30 casualties. At the next crossing located a half-mile downstream, Garnett posted 10 sharpshooters behind driftwood on the riverbank. Taliaferro urged Garnett, who was mounted, to ride to safety. “The post of danger is now my post of duty,” replied Garnett. While Garnett and an aid, Sam Gaines, were posting the men, they heard a wounded Rebel screaming in agony on the far bank. Gaines rode back to retrieve the soldier, who had suffered a horrible wound in the lower face. By then, sharpshooters on both sides were sniping at each other. Bullets zipped through the air Black smoke hovered over the rushing water.

Gaines ducked, and Garnett gently scolded him for it. Sergeant R.F. Burlingame of the 7th Indiana Regiment was one of the Federal sharpshooters tracking Garnett. At the moment that Garnett turned in his saddle and ordered his men to retire, he was struck in the back. He tumbled hard to the ground, dying almost instantly. The Rebels had withdrawn, leaving Garnett’s body to the mercy of the Yankees.

The Federals broke off their pursuit. They returned Garnett’s body to his family for burial. He was the first of many generals to fall in the long war.

Very good article. Like to read more. S