By Alice M. Flynn and Allyn Vannoy

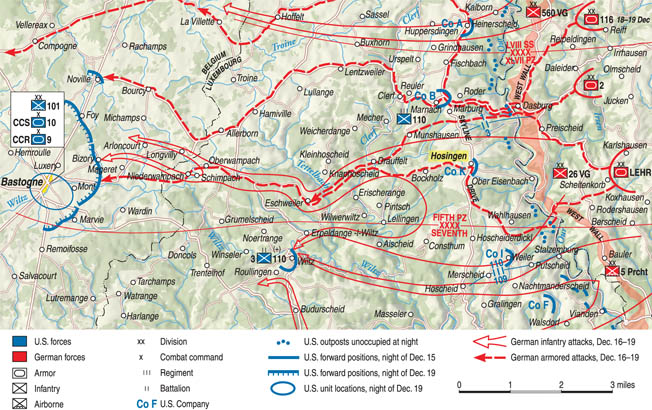

First Lieutenant Tom Flynn and his fellow POWs remained locked inside their boxcar prison on a Frankfurt railroad siding on Christmas Eve, 1944, as air raid sirens wailed and bombs exploded throughout the city. A number of boxcars were hit, sending shock waves and shrapnel throughout the rail yard. The sound of explosions and shrapnel hitting the side of the boxcar was deafening and terrifying. This was not where Flynn, commanding K Company, 110th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division, had envisioned himself being just a few weeks earlier.

Thomas Flynn in the “Bloody Bucket”

Thomas Joseph Flynn was born on August 21, 1920, the fourth child of Richard E. and Josephine Engfer Flynn, a working-class family living on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Thomas graduated from high school in June 1937, having studied French and achieving fluency in German that he would find useful a few years later. In October 1937, he joined the 165th Infantry Regiment, 27th Infantry Division (New York National Guard), which three years later,would become one of the first National Guard units “federalized” and placed on active duty more than a year prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

After the United States entered the war, Sergeant Flynn applied for and was accepted for Officers Candidate School. After OCS, he was assigned to the 353rd Infantry Regiment, 89th Infantry Division, at Camp Carson, Colorado. While there he met Army Nurse 2nd Lt. Anna Bennedsen. Following a short romance, they wed on September 13, 1942.

In March 1943, Flynn was promoted to first lieutenant in the regiment’s antitank company. He was then reassigned five months later as company commander of E Company, 85th Mountain Infantry Regiment of the newly formed 10th Mountain Division. Injured in a rock-climbing exercise at Camp Hale, Colorado, in October, he remained hospitalized until the end of the year.

While still recovering, he was assigned as an infantry instructor until restored to full service in June 1944. He then shipped to the ETO on September 23, assigned to a replacement depot in France, and subsequently to the 28th Infantry Division (known to the Germans as the “Bloody Bucket” given its red keystone shoulder patch).

Just prior to Lieutenant Flynn’s arrival at the division, the 28th had completed a near disastrous operation in and around the village of Schmidt in the Hürtgen Forest, where it suffered heavy casualties. On November 8, Flynn was made temporary commanding officer of K Company, 110th Infantry Regiment.

Some 500 replacements were assigned to fill the devastated ranks of the 110th, 100 of them to K Company, though this still left the company understrength (the authorized strength of a rifle company was 193). Despite this, the unit was immediately ordered to continue operations in the Hürtgen Forest during November 10-13. Machine-gun fire from well-positioned German bunkers, along with antipersonnel mines, mortar attacks, and artillery tree bursts, took a devastating toll on the 110th.

In addition, freezing weather, a foot of snow, and a lack of proper winter gear caused many of the GIs to suffer frostbite, Lieutenant Flynn among them. By the time the 110th left the forest, there were only a handful of men left in K Company that had been with the unit prior to arriving in Europe.

The 28th Division was transferred to a supposedly “quiet area” in the Ardennes Forest, 60 miles to the south. After treatment for knee injuries sustained in combat and frostbite, Flynn rejoined the company on November 20 at the village of Hosingen, Luxembourg.

The company commander, Captain Frederick Feiker, who had been injured prior to action in the Hürtgen Forest, had not yet returned to duty. Thus, despite only having just arrived at the unit, it fell to Flynn to help rebuild and prepare it for action. His prior duty as a training instructor served him well.

The Defenses of Hosingen

Hosingen was one of five company strongpoints the 110th Infantry had established along the front. The village was defended by the 1st and 2nd Platoons of K Company, 3rd Platoon having been assigned to a position just south of the village. Also in the village was B Company (with only 125-130 men) of the 103rd Engineer Combat Battalion, under Captain William H. Jarrett, that was responsible for road maintenance in the area. In support were the 2nd and 3rd Platoons of M Company, the battalion heavy weapons company.

Additional support was provided by attached elements (about 30 men) with three 57mm antitank guns and three .50-caliber machine guns positioned at a crossroads south of Hosingen along Skyline Drive, the main north-south road paralleling the front.

Hosingen was at the middle of the 110th’s 15-mile-long sector, set on the Ober Eisenbach-Hosingen-Drauffelt road that led west to the town of Bastogne. The village was situated on a ridge top with a twisting road to the east, dropping down to the Our River, and to the west to bridges over the Clerf River at Drauffelt and Wilwerwiltz.

Upon arriving at Hosingen, Lieutenant Flynn quickly assessed the situation. Most of the company’s NCOs had come from the 41st Replacement Battalion and seen action in the Hürtgen Forest along with Flynn. There were also some 20 RTD (return-to-duty) men who had recovered from injuries or wounds.

Flynn directed his men in improving defensive positions previously established by the 8th Infantry Division, relocating some mines, and adding minefields along likely avenues of approach. But on-hand ammunition stocks were minimal and the supply system promised little relief.

The communications network was well established with phone lines to the 3rd Battalion command post at Consthum, the engineers, each platoon CP, northern and southern observation posts (OPs), the mechanized cavalry units on either flank, and the other companies of the 110th Infantry, as well as the regimental headquarters in Clervaux. SCR-300 radios provided communications redundancy to the 3rd Battalion net and with the 1st and 2nd Platoon CPs.

K Company was assigned a two-mile stretch of Skyline Drive with patrols monitoring the area between the highway and the Our River during the day, along with OPs near the river, but which were pulled in during the night.

Along with preparing defenses and patrolling, the unit also conducted tactical training of its many replacements in scouting and patrolling, sniping, and observation.

Flynn established the K Company CP in the Hotel Schmitz, a two-story structure in the middle of Hosingen. The 1st Platoon, K Company held the northern perimeter of the village. First Lieutenant Bernie Porter’s 2nd Platoon covered the south end of town and 3rd Platoon was positioned 250 meters southeast of Hosingen on Steinmauer Hill. Support elements of M Company’s 2nd Platoon were positioned to support both 2nd and 3rd Platoons of K Company, covering the southern and southeastern approaches to Hosingen.

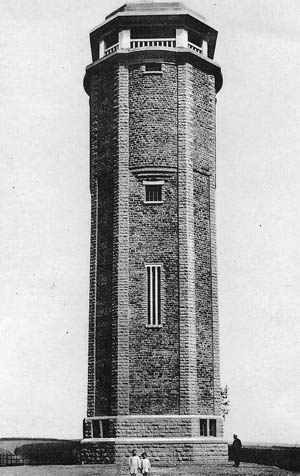

A section of 81mm mortars was set up behind one of the buildings near the center of the village. A pair of .30-caliber machine guns from K Company’s weapons platoon were placed in the northern end of Hosingen covering Skyline Drive, and its 60mm mortars were set up in a courtyard. Squad-strength OPs were maintained on Steinmauer Hill and in the water tower at the northeast edge of Hosingen. All in all, the village seemed to be well defended against just about anything the Germans might throw at it. Or so the men of K Company thought.

Manteuffel’s Volksgrenadiers

Captain Feiker returned to duty on December 6 and Flynn became his executive officer. GIs on the line had increasing indications that something was developing on the far side of the Our River—sounds of heavy vehicles, plus information from prisoners—but higher command failed to take the intelligence seriously.

By mid-December, on the other side of the Our, the German 26th Volksgrenadier Division (VGD) was preparing for operations against the Americans as part of the forthcoming Ardennes offensive. Plans called for Hosingen to receive the attention of an entire battalion.

The 26th VGD was considered to be the best infantry division of General Hasso-Eccard Freiherr von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army. Twelve thousand men strong and under the command of Maj. Gen. Heinz Kokott, the 26th VGD’s mission was to capture the positions held by the 110th, seize control of the bridges over the Clerf River, and then move on to Bastogne by the end of the second day of the offensive.

On the evening of December 15, K Company’s southern OP picked up the sound of what were believed to be motors coming from the direction of the Our, but the sounds soon faded. As a precaution, the company’s mortars were shifted to new positions.

Around 3 am on December 16, elements of the 304th Panzergrenadier Regiment, 2nd Panzer Division and the 39th and 77th Volksgrenadier Regiments of 26th VGD began quietly crossing the Our River in rubber boats, hidden by a thick blanket of fog.

The 77th Volksgrenadier Regiment’s mission was to bypass Hosingen and head for Drauffelt to seize the Clerf River bridges, which German armor planned to cross by nightfall on December 16 if they were to take Bastogne the following day. Delays could be ill afforded.

“The Town Was Pretty Well Lit Up”

American defenses were quietly surrounded by German units. Once in place, some of the Germans began attacking American outposts. But most of the German units waited for the artillery bombardment that would signal the beginning of the offensive.

At 5:30 am, a freezing cold Saturday morning, GIs in the OP atop the water tower in the northeast corner of Hosingen noticed hundreds of “pinpoints of light” to the east. Seconds later, artillery shells began to splatter in Hosingen and the surrounding area, severing wire communications.

During the barrage, Lieutenant Flynn dashed to the north end of the village to check on 1st Platoon while Lieutenant Porter went to the south end to the 2nd Platoon. The 45-minute artillery barrage set five buildings on fire. “The town was pretty well lit up,” Flynn recalled, illuminating the whole ridge top.

When the shelling ended, some members of K Company noted that shells had fallen in the area where the company mortars had been located a few hours before; luckily, no casualties had been suffered among the defenders.

Between 6:15 and 7:15 am, the sound of troops moving could be heard to the north, but it was still too dark to see. At daylight, around 7:30, through the smoke and morning fog the GIs could make out shadows moving in the distance across Skyline Drive. Flynn ordered his men to open fire on the shadows. The machine guns knocked down quite a few Germans and interrupted their westward movement. The American fire was disciplined, the GIs not firing unless they were sure of their targets.

At the same time, Sergeant James Arbella, a 60mm mortar section leader of M Company, and Staff Sergeant Henry Shanabarger climbed the water tower where the two GIs of 1st Platoon were stationed as lookouts and gave their mortar crews direction as to targets along Skyline Drive, helping to pin down the Germans.

As the water tower lookouts scanned the area around the town and the fog lifted, they observed a company of white-clad German soldiers of the II Battalion, 77th Volksgrenadiers charging across open fields from the east. They quickly alerted the GIs on the ground. The combination of mortar shells, BARs, machine guns, and rifle fire shattered the enemy assault. The surviving Germans retreated, leaving behind scores of dead and wounded.

An initial rush of the 77th Grenadier Regiment along the Ober Eisenbach-Hosingen-Drauffelt road overran the outpost on Steinmauer Hill and cut off the 3rd Platoon, K Company and the antitank unit south of the village. Some of these troops were able to retreat to the west, while others continued to fight on until killed or captured.

Captain William Jarrett, commanding officer of B Company, 103rd Engineers, had climbed Hosingen’s church steeple, then contacted Lieutenant James Morse, commanding a section of M Company 81mm mortars in the village and informed him of the targets. Morse’s mortars went into action, pounding the Germans and temporarily halting their movement across Skyline Drive to the south of the village.

From his Hotel Schmitz CP, Captain Feiker requested artillery support, but the nearest artillery unit, Battery C, 109th Field Artillery Battalion, located directly to the west of the ridge, was also under attack by German infantry that had bypassed Hosingen. So the village’s defenders had only their own mortars for support, as Captain Jarrett’s engineers had not yet joined in the defense of the town.

Capturing the German Battle Plans

When other German troops managed to penetrate the southern outskirts of Hosingen, Lieutenant Porter’s men engaged them in house-to-house fighting. During the action, a German officer who possessed a map outlining the German XLVII Panzer Corps’ attack plan all the way to Bastogne was captured.

Recognizing the significance of the map and that the attack was actually part of a much larger counteroffensive, Captain Feiker attempted to have a runner carry it to the regimental CP at Clervaux. But by then there were too many Germans between the two towns, and the runner only made it a mile out of Hosingen before being forced to return.

Feiker then contacted Major Harold F. Milton, 3rd Battalion CO, at battalion headquarters to inform him of the situation and tell him that it was impossible to get the map to Colonel Hurley E. Fuller, commanding the 110th Infantry, in Clervaux.

Milton ordered Feiker to hold his position, promising that L Company, in reserve near the 3rd Battalion CP, would come forward to help and also bring up more ammunition; however, L Company became involved in its own fight and never reached Hosingen.

Sufficient information had reached Colonel Fuller and Maj. Gen. Norman D. Cota, the 28th Division’s commanding officer, for them to realize that the 110th’s line companies were facing a massive German assault and that most of their positions were surrounded or cut off.

Fuller tried to convince Cota to release his 2nd Battalion from reserve to bolster his positions around Clervaux, but Cota didn’t want to commit his reserves so early in the battle. However, at 7 am, the general alerted the 707th Tank Battalion to prepare to counterattack. By 9 am, Major R.S. Garner and 16 Sherman tanks of the 707th’s Companies A and B moved out from Drauffelt and Wilwerwiltz, heading for Clervaux to support the 110th.

By 8 am, Captain Jarrett and the officers of K Company concluded that the enemy might next attack the village from the west, so Jarrett sent his 1st Platoon, under Lieutenant Cary Hutter, to the western edge of the village, shielding the M Company mortar section. Jarrett’s 2nd Platoon, led by Lieutenant John Pickering, set up a roadblock on the Skyline Drive at the southern edge of Hosingen.

The 3rd Platoon of engineers, under Lieutenant Charles Devlin, took up positions in the northeastern part of Hosingen, where they could provide fire support for the K Company outpost in the water tower. Jarrett moved his company CP to a hotel in the northern part of town between the left flank of the 3rd Platoon and the right flank of the 1st Platoon.

Meanwhile, moving beyond the range of the Hosingen weaponry, German infantry continued to bypass the village to the north and the south throughout the day.

Flynn’s Clash Near the Water Tower

When elements of the 707th Tank Battalion got to Clervaux, Colonel Fuller split the tank force into platoons and sent them forward. Part of B Company headed towards Munshausen and Marnach.

The tanks fought their way through the German infantry to the edge of Hosingen. When they reached the intersection of Skyline Drive on the south edge of the village around 1 pm, they took up defensive positions and stayed there for two hours but did not contact the troops in Hosingen.

At 3:15, 1st Lt. Robert Payne led the 707th’s 3rd Platoon of A Company south along Skyline Drive from Marnach, which had just been retaken by an American counterattack. With machine guns blazing, Payne’s tanks entered the north end of Hosingen at about 4 pm.

At about the same time that Payne’s tanks arrived, the four Shermans of the 1st Platoon, B Company that had taken up position at the south end of the village suddenly pulled up stakes and headed south toward Hoscheid. Lieutenant Payne scrambled to get his tanks into defensive positions before dark.

Feiker sent three tanks, accompanied by infantrymen, to the high ground on Steinmauer Hill to help slow the enemy traffic coming up the Ober Eisenbach road; Payne moved his own tank to cover the road to the south of the village. The remaining Shermans positioned themselves to cover Skyline Drive to the north.

At 4 pm, German engineers finally finished construction of bridges over the Our at Gemünd, Dasbürg, and Ober Eisenbach, permitting German armor to cross the river. The Germans desperately needed to eliminate the stubborn American position at Hosingen, regain valuable lost time, and clear the 26th VGD’s main supply route. So, at 5 pm, three panzers from the Panzer Lehr Division’s armored reconnaissance battalion, Kampfgruppe von Fallois, were to be sent against Hosingen.

The Germans were torn between committing the unit to seize Bastogne or using it against Hosingen. To assist Kampfgruppe von Fallois, General Kokott called on part of his division reserve, the I Battalion, 78th Grenadier Regiment. The battalion assembled two kilometers west of Ober Eisenbach while the II Battalion bypassed the town and headed for the Clerf crossing at Wilwerwiltz. Two German panzers appeared on the high ground on Steinmauer Hill and fired on the three Shermans there, forcing the tanks to withdraw into Hosingen near 2nd Platoon, K Company.

German traffic resumed on the Ober Eisenbach-Bockholtz road and passed Hosingen after the three Shermans withdrew. But Payne’s crews spent the evening periodically sneaking out of their defilade positions, lobbing a few shells at the Germans, and then racing back to cover.

The Germans continued firing on Hosingen all night. German patrols were also spotted moving close to the village in preparation for another assault. In the morning the main German attack struck the north part of the village in the area of the 1st Platoon, near the water tower.

The Germans pushed forward, disregarding their losses, capturing a few houses on the outskirts of the village. Vicious and often hand-to-hand fighting continued until around 10 pm.

Lieutenant Flynn became involved in one of these skirmishes, killing a German officer. Searching the officer’s body, he discovered a document that provided details on American positions along the front line; he reported this to Captain Feiker.

Throughout the action, the GIs in the water tower continued to provide the location of the Germans to the 81mm and 60mm mortar crews.

Driving Back the German Assaults

Back in his CP, Feiker assessed the situation. Even as the fighting died down, German patrols continued to work their way to the edge of the village. Amazingly, there were few American casualties. As the day ended, the American troops in Hosingen were still holding.

Just before dawn on December 17, small groups of German troops from the 78th Grenadiers moved to the high ground on Steinmauer Hill and began to fire into K Company’s positions.

German commanders were growing increasingly impatient as the Americans continued to impede their supply route, restricting the flow of matériel to units attempting to cross the Clerf River, delaying their advance. They therefore made the decision to divert Panthers and Mark IV panzers from the 2nd Panzer Division and move them south to help the II Battalion, 78th Grenadier Regiment assault the village.

About 9 am, with the panzers and grenadiers in place, artillery began to rain down on Hosingen. Once again, the town was set ablaze. Captain Jarrett moved his Engineer’s CP to the basement of a nearby dairy.

As the artillery fire lifted, the Germans began another assault on the village perimeter from several directions. The Americans’ already depleted ammunition supply was running low.

The fighting lasted for an hour, but the Germans were again unsuccessful in dislodging the Americans, suffering heavy casualties in the process and then pulling back around 10 am, leaving the ground strewn with wounded and dead.

About an hour later, two half-tracks were observed moving rapidly down Skyline Drive from the north, the lead vehicle being an American half-track. But it was not clear as to the identity of the second vehicle. Flynn and Payne’s men held their fire to see what would happen next. Payne cautiously kept his tank in its defilade position, awaiting developments.

When the half-tracks were about 1,000 yards from the American positions, the two wheeled about and sped back up the road. The Sherman crew identified the second halftrack as German. Still suspicious of what the Germans were up to, the GIs kept watch and shortly afterward the lookouts in the water tower sighted two German Panthers hiding to the northwest in a position from which they could have blasted the Sherman had it revealed its location.

The German commanders were increasingly annoyed at the impact the water tower OP was having on their operations. At 1 pm, the two Panthers opened fire on the tower, but the Americans suffered no casualties within the hardened structure, the outer walls of thick concrete supported by a steel shaft column enclosing a circular steel stairway in the center.

Surrender at the Water Tower

Before long, six more Panthers and Mark IVs from the 2nd Panzer Division, pulled from their position three miles to the north in Marnach, joined the other German panzers. As they fired at Hosingen, German small-arms fire once again increased as grenadiers advanced from the north.

Although U.S. machine guns and mortars pinned down the Germans to the north, more grenadiers attacked from the west. Captain Feiker tried to send bazooka teams to drive off the Panthers, but German small-arms fire prevented the Yanks from moving beyond the edge of the village.

The fighting continued all afternoon. The eight panzers began to work their way closer to the northern edge of the village behind supporting infantry, wary of the Shermans and possible bazooka teams. Buildings in Hosingen were slowly and methodically reduced to rubble.

Lieutenant Payne shifted his Shermans from south to north and west to engage the panzers. Flynn’s 1st Platoon fired on the attackers while mortar shells, still directed by observers in the water tower, pinned down the enemy. Despite the Americans continuing to inflict significant casualties, more grenadiers kept coming from the west.

When communications with the water tower were lost, Sergeant Lloyd Everson, in position a few hundred yards south of the tower, ran a new phone wire. Dodging a hail of fire that kicked up the snow beside him as he ran, Everson made it to the tower only to find that the wire had been cut about 15 or 20 feet from the door of the structure. Exposing himself once again, he was able to repair the phone line.

German infantry worked their way into the village from the north and the west, their numbers too great to be stopped. They were finally successful in taking out both of 1st Platoon’s machine guns covering Skyline Drive as well as a .50-caliber machine gun. Eventually, all the 60mm mortars either ran out of ammunition or were destroyed, and even rifle ammunition was running out.

The water tower went next.

One of the panzers fired two rounds at the tower. Not satisfied with the results, it moved to a new position. Sergeant Everson, firing at the approaching German infantry, watched the tank out of the corner of his eye. The next tank shell exploded and blew Everson down the stairs. Stunned, he was unable to see or hear. When his sight and hearing returned, he found a German pointing a machine pistol at him.

A German medic bandaged wounds to Everson’s face and hands. Two Germans marched several GIs they’d taken prisoner about a hundred yards with their hands over their heads. Everson noted by his watch that it was 4:15 pm.

House-to-House in Hosingen

During the fighting, Flynn discovered that the radio in the 1st Platoon CP had been damaged. To report 1st Platoon’s situation and the enemy attack on the north edge of town to Captain Feiker, he ran a gauntlet of fire through the rubble-strewn streets, even crawling at times to avoid enemy tank fire. He dodged bullets and shells all the way to Feiker’s CP, where he learned that the Germans was moving into the southern end of Hosingen.

By dusk the Germans were inside the town, and fighting became house to house and hand to hand. When forced to withdraw, the GIs set booby-traps that inflicted casualties or started fires. The fires lit up the fields around the village, exposing the Germans to gunfire. But despite American efforts, the Germans pressed forward as their numbers in the village continued to grow.

Gradually, most of the men from 1st and 2nd Platoons of K Company, Lieutenant Payne’s Sherman crews, and the Engineer’s 3rd Platoon under Lieutenant Devlin, worked their way back to the vicinity of the Hotel Schmitz. However, Captain Jarrett’s 1st Platoon, under Lieutenant Hutter, was now isolated in a small pocket to the west, Flynn’s 1st Platoon had a few small groups of men cut off in the north, and Lieutenant Pickering’s 2nd Platoon had individuals and groups of two or three still scattered throughout the town.

Payne’s five Shermans had limited movement so they set up a perimeter defense at Feiker’s CP. Two tanks were knocked out by antitank rockets or panzerfausts.

Feiker met with his officers to assess the situation: small pockets of his and Jarrett’s men were cut off, their ammunition was almost gone, there were only three operating tanks, and there was no artillery support or relief force on the way.

At one point, two groups of grenadiers stormed Captain Jarrett’s command post in the dairy, but he and his men fought them off.

At 4 am on Monday, December 18, Captain Feiker once again spoke with Major Milton, explaining K Company’s situation and asking for instructions. Milton ordered the Hosingen defenders to infiltrate westward through the German lines in small groups while it was still dark.

But Feiker said it was too late: “We can’t get out, but these Krauts are going to pay a stiff price.…” Milton then told Feiker that he and his men should do whatever they saw fit.

The Decision to Surrender

Feiker promptly called together his officers. K Company had only two rounds of smoke ammunition left for the 81mm mortars, the last 60mm mortar had been knocked out, and rifle ammunition was nearly gone. They agreed with Feiker that there was little chance of escaping through the German lines.

Flynn recommended that they surrender so the men would have a better chance of survival. Feiker conceded and the other officers agreed. Feiker then radioed Milton to tell him of their decision. In the meantime, all the engineer trucks and road equipment were burned, K Company vehicles and their garage were set on fire, the tanks were rendered useless, and all weapons were destroyed.

Between 8 and 9 am, German snipers and panzers once again began to fire on Hosingen. To prevent additional American casualties, Captains Feiker and Jarrett had a white flag hung from a building on the north end of town and had white panels hung on the tanks. The Germans ceased fire immediately. Together the American commanders walked out into the open to meet with the ranking German officer on the scene, a colonel from the 78th Grenadiers, and discussed surrender.

At 10 am, Feiker and Jarrett returned at gunpoint, accompanied by German officers and troops. They told their men to come out with hands on their helmets and to assemble in front of the church.

Out of a force of some 300 defenders, casualties included just seven killed and 10 wounded, two seriously. The defenders had inflicted an estimated 2,000 casualties on the Germans, including more than 300 killed.

The Germans were surprised when the American defenders gathered in the street. They could hardly believe that such a small force had put up such a fight against some 5,000 Germans and suffered so few casualties while inflicting such enormous damage on their forces.

Hosingen was the last of the 110th Infantry’s garrison towns to surrender, having held out and delayed the Germans for 21/2 days, giving First Army time to rush troops to Bastogne.

POW March to Germany

The Germans searched the GIs, taking anything of value. The American officers could only watch in silence as their men were yelled at, slapped, and stripped of their valuables. Many of the enlisted men were also forced to give up their overcoats or field jackets, overshoes, and exchange their boots for the inferior, ill-fitting boots of the German soldiers. The situation was tense as two of the defenseless GIs were shot by one of the Germans.

Lieutenant Flynn and the other American officers were taken to a house at the south end of Hosingen where they were searched and then interrogated about the location of minefields and booby traps—German vehicles having detonated several mines.

The enlisted men were moved out into the open fields around the town to help with the dead and wounded. Medic Wayne Erickson was one of the men forced to help bury some of the 300 dead Germans, then care for the wounded prisoners.

Once the officers rejoined the group, the POWs were corralled into a fenced-in area while the Germans tried to figure out what to do with them. It was late in the day when they were finally marched to Eisenbach and locked in a small church for the night. Most of the GIs had not slept for three days and were exhausted.

The Germans had promised a hot meal at Eisenbach but that did not happen. The POWs did their best to get some sleep on the floor or church pews, but the building had no heat.

The next morning the POWs were given only a small cup of hot coffee for breakfast. Standing outside the Eisenbach church, they saw large numbers of heavy artillery pieces moving up the road from the south on the west side of the Our River and realized that the Germans had captured all the frontline towns that had been held by the 28th Infantry Division.

Once again, the K Company prisoners were formed into columns to continue their march to Prüm Germany, a 24½-mile, two-day journey. When they arrived in Prüm late on December 20, other prisoners were added to the group from the 3rd Platoon of K Company, which had been overrun on December 16 on Steinmauer Hill. POW columns from both the 28th and the 106th Divisions also converged in Prüm for transport to prison camps.

The men did not get much rest as the Germans rerouted them to Gerolstein, another 12½ miles away. The weather continued to grow colder. The winter of 1944-1945 would prove to be one of the coldest on record in Germany and would take a devastating toll on the POWs.

The prisoners did not receive any rations until the following day, December 21, when they were issued a small amount of hot soup upon their arrival in Gerolstein. They were starving and what they were given did little to fill their empty stomachs.

In Gerolstein, they were then issued some straw to sleep on and were locked in an icehouse overnight. As more prisoners were added to the group, Captain Feiker instructed his men not to speak to anyone they did not know. He was concerned that the Germans would mix spies in with the prisoners in an attempt to gather intelligence. Thankful to be off their feet and out of the winter weather, the men tried to rest and tend to their aches and pains as best they could.

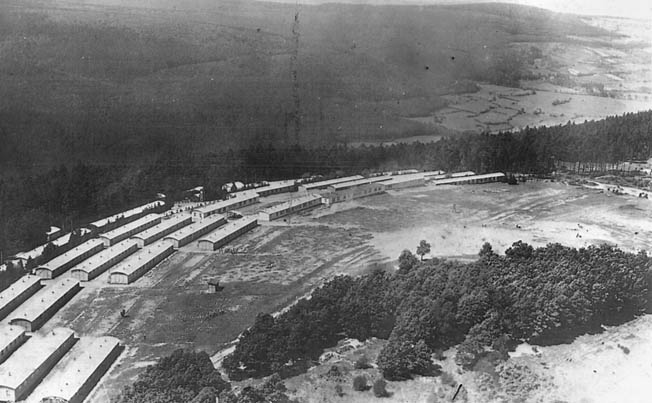

The Notorious Stalag IX-B

The next day, the Germans issued a two-day food ration for their next move. It consisted of two packages of German field biscuits per man and a can of cheese to be split between six men. The POWs were divided into officers and enlisted men and then split into groups of about 50 to be loaded into boxcars, which were then locked.

Lieutenant Flynn’s train was headed for Frankfurt, Germany, 147 miles away. The guards rode in separate cars and dismounted to patrol whenever the train stopped. The train pulled into the Frankfurt marshaling yards later that day. The POWs remained locked inside the boxcars on a rail siding for two more days—waiting, worrying, and wondering—and it was now Christmas Eve, 1944.

It had been nine long days since the Germans’ Ardennes counteroffensive had begun, and a break in the weather finally came on December 24. The U.S. Eighth Air Force and England’s Royal Air Force together launched massive air attacks intending to cut German communications and transportation routes. As a result, 143 planes headed for Frankfurt.

Air raid sirens began to wail and bombs began exploding throughout the city. A number of boxcars were hit not far from where Flynn’s car was sitting, sending shock waves and shrapnel throughout the rail yard. The prisoners were terrified; they had no idea if the next bomb would land directly on them. In a panic, one man tried to escape out a small window in the boxcar but was immediately shot and killed by a German guard. Fortunately, there were several trains parked between Flynn’s boxcar and the exploding bombs, absorbing the shrapnel.

The next day, Christmas, the POWs were given one Red Cross parcel per five men to share in lieu of German rations. The following day, the trains finally headed northeast out of Frankfurt for Bad Orb, Germany, and Muhlberg, in Poland.

On December 26, their train pulled into Bad Orb, where Flynn and hundreds of other GIs were organized into columns and marched up a hill to Stalag IX-B. Flynn’s group was the first wave of American soldiers to be sent there, and the camp authorities were unprepared for them.

Flynn was one of 250 officers jammed into a barracks they would temporarily occupy before being moved to another camp. Most of the men were issued a single blanket that was worn and threadbare. Some men had no blankets and many had to sleep crowded together on the bare wood floor.

Conditions at Stalag IX-B were terrible; it was considered one of the worst German POW camps that held American prisoners. Many of the rooms had broken windows and the wood or cardboard covering the holes did little to keep out the below-freezing weather. There were only three primitive latrine houses and three latrine trenches. There was no hot water, soap, or washrooms. The men had to make do with just one or two cold water taps in each barracks.

German rations were minimal. The POWs typically received a coffee-type beverage for breakfast. Some type of vegetable soup was served at noon. Occasionally, a dead horse would be dragged through the camp, meaning the prisoners might find a piece of meat in their soup. Even a dead bug in the soup was deemed acceptable—it was just another form of protein to the starving POWs. Late in the afternoon, each man received one-sixth of a loaf of bread, a small portion of margarine, and occasionally, a little cheese or meat—usually horsemeat.

In compliance with the Geneva Convention, the officers were separated from the enlisted men. Officers were not allowed on work details outside of camp, which meant there were no additional opportunities to supplement the minimal rations they were given, nor chances to gather firewood for the stoves in their barracks.

Not everyone from Hosingen was sent to Stalag IX-B. Captain Jarrett, 103rd Engineers, Colonel Fuller, 110th Infantry, and other officers of the 110th were taken to a camp in Poland: Stalag IV-B at Mulburg, where they were liberated by the Russians in late January 1945 after just a month of captivity.

Flynn’s Captivity in Hammelburg

The Germans divided their POW camps into Stalags for enlisted men and Oflags for officers. On January 11, 1945, Flynn and 452 officers, 12 noncommissioned officers, and 18 privates were relocated to Oflag XIII-B, 34 miles south near Hammelburg.

Flynn and his group were the first Americans to be sent to this camp as well. They were lodged in premises formerly occupied by Serbian POWs.

Flynn kept track of the days spent in captivity. As mid-January approached, it would be his wife Anna’s 25th birthday. This was not how he had pictured them celebrating. He knew she was probably worried about him and wondering if he was still alive.

The Hammelburg camp was old and rundown. The International Red Cross had been unable to improve living conditions. Only one hot shower was provided a month and lice were prevalent in all the barracks. The lack of hot water to clean kitchen utensils led to frequent outbreaks of dysentery, further weakening many men in the camp. Many POWs lost more than 50 pounds during captivity and their muscle strength deteriorated significantly, leading to immobility or, in some cases, death. Flynn was no exception, dropping from 165 to 125 pounds on his 5-foot, 10-inch frame.

Barrack temperatures averaged about 20 degrees Fahrenheit. throughout most of the winter so the POWs—40 per room—tried to keep from freezing to death by wearing all the clothing they could find. Life at Oflag XIIIB was reduced to the basics: scrounging enough food to stay alive and finding ways to keep warm.

The prisoners also feared for their lives after several men were shot and killed by guards for minor offenses. The POWs were finally allowed to send their first Red Cross cards to their families, but the camp never received any incoming mail.

Flynn kept his thoughts to himself as he found it difficult to establish friendships. Despite the cold, he preferred to be outside as much as possible, spending his time talking through the fence to the Serbian officers in Oflag XIII-A. He developed a friendship with one of them and, as a token of friendship, the man handed him a beautiful, hand-embroidered silk scarf through the fence––a gift he would keep for many years after the war.

The Evacuation of Hammelburg

On March 27, 1945, General George S. Patton Jr. sent a 293-man task force with two companies of Sherman tanks, under Captain Abraham Baum from the 4th Armored Division, 50 miles into enemy territory in an attempt to rescue his son-in-law, Lt. Col. John K. Waters, and liberate the Hammelburg camp.

After the tanks broke down the camp’s gate, Colonel Paul Goode, the senior ranking officer at the camp, let each man decide whether they wanted to try and make it back to the American lines with Baum’s unit, strike out cross-country on their own, or stay at the camp if they were too weak to travel, hopeful that other American units would be coming soon.

Flynn and four other officers decided to try for the American lines on their own and made plans to head southwest; Flynn secured a compass and a case of C rations and they headed through the woods toward Gemünden.

They soon came upon a small house near the edge of a stone quarry where an older German couple lived. With Flynn acting as interpreter (he had taken German in high school), they convinced the couple that they meant no harm and that they were only trying to get back to the American lines. The woman gave them milk and the first good cup of coffee they’d had in months while she heated some of their rations on the stove. The elderly man gave them a map and information to help them with their escape.

After evading capture for three days and traveling more than 13 miles, they were recaptured on March 30 by a search party looking for escaped prisoners. Once again, Flynn’s high-school German came in handy as he explained that they were unarmed POWs and that they had become lost in the woods. They were returned to Hammelburg where they learned that Task Force Baum had been shot up trying to get back to the American lines and that all the prisoners had either been recaptured or killed in the fighting.

The evacuation of the Hammelburg camp had been under way for several days since their escape, as the Germans moved the prisoners farther into the interior of Germany to keep them away from the advancing Allied armies.

The following morning, Flynn and all the remaining POWs were loaded into unmarked boxcars, en route to Nuremberg. Approximately eight miles outside of Hammelburg, American P-51s strafed their unmarked train. The fighters flew the length of the train, shooting up the engine at the front. As the train slowed to a stop, Flynn and the other POWs convinced their guards to open the doors before the fighters came back. The guards jumped out first, and the POWs followed, taking cover away from the train. The fighters returned to rake the train again, but the men were far enough away by then to be safe.

The senior U.S. and British officers protested that their men would not ride any farther unless the train was plainly marked as a POW train. The German commander then gave the men the choice of walking or riding the remaining 90 miles. The majority chose to walk to Nuremberg.

March to Moosburg

The warmer spring weather made the march much easier. Flynn was happy to be out from behind the barbed-wire fences and chose to be a straggler at the end of the column, walking as slowly as the guards would let him in order to delay their arrival at the next camp. Anything was better than confinement.

When Flynn’s group reached Nuremberg and Stalag Luft III, he learned that the first group of American prisoners evacuated from Hammelburg had included Captain Feiker, but that Feiker had been killed during an Allied air raid of Nuremberg on April 5 as their column was being marched through the city.

Stalag Luft III had been so badly damaged by air raids that Flynn’s group was only kept at there for two days. Flynn was marched through Nuremberg en route to Stalag VII-A in Moosburg, another 90 miles away. By this time, American fighter planes and bombers had destroyed much of Nuremberg so the POWs, especially those who were pilots, were met by angry and hostile mobs as they were marched through the bombed-out streets.

Flynn understood what the civilians were saying and told all the pilots around him to hide the pilot wings on their uniforms. When a group of civilians would press too close, Flynn would point to the crossed rifles insignia on his uniform and tell them, “fuss soldaten” (foot soldiers or infantry). He was able to save the pilots in his group from harm in this way, and they made it safely through the city without injury. Some POWs in other groups were not so lucky and were pelted with stones by the mobs.

Near exhaustion, Flynn lost track of time on the march to Moosburg. The prisoners walked as slowly as the German guards would allow in an attempt to prolong the journey. By this time, both prisoners and guards were scrounging for food from the Bavarian farmers, and thanks to warmer weather, they were able to sleep in haystacks in the fields at night.

Yet, they were still not safe. They were once again attacked by an American fighter plane near a railroad overpass. Flynn wasn’t sure if they had been the primary target this time, but some POWs at the front of the column were injured. Flynn was content to be one of the stragglers at the rear of the line.

Flynn’s POW column arrived at Stalag VII-A about April 15. The camp was meant to hold 3,000 prisoners but, as of mid-April, the population had swelled to more than 100,000. There were men from every nation Germany had fought for the past five years.

After Flynn and the other POWs were shown their billets, American and British airmen there gave each of the new arrivals a Red Cross package. This was the first time in four months of captivity that he had received a package just for himself. The airmen shared rumors that Hitler had ordered all American officers in the camp killed rather than surrendering them to any liberators.

Liberation

On April 28, Flynn and the other prisoners heard artillery fire in the distance to the southwest. By sunrise the next morning, sounds of an approaching armored column could be heard, sounds that excited Flynn and the rest of the prisoners.

With the advancing American Army nearby, SS troops began to fire their weapons into the camp in an attempt to carry out Hitler’s orders. The camp guards told the POWs to stay inside with their heads down as the prison guards and the German Army fought off the Gestapo and SS and saved the prisoners’ lives.

The fighting was over in less than an hour, and Flynn soon felt the vibration of tanks approaching. It didn’t take long for the sound of the tanks to be drowned out by the sounds of euphoria erupting from the men in Stalag VII-A.

The Shermans of the 14th Armored Division crashed through the fences of the compound and were engulfed by a sea of ragged, emaciated POWs. When the camp commandant surrendered to Brig. Gen. Charles H. Karlstad, 14th Armored Division, the Americans assumed control of the camp.

As Flynn joined the celebration, he witnessed 1st Lt. Martin Allain, a bomber pilot who had been a POW for more than two years, reveal a treasured American flag he had been hiding for most of that time. When Allain climbed up the camp flagpole with Old Glory in hand, the entire camp went silent as he replaced the ugly swastika with his beautiful Stars and Stripes at 1 pm on April 29, 1945.

Regardless of nationality, every man immediately came to attention and saluted the American flag. The prisoners were overcome with the emotion that most had locked away for months, if not years, and almost every eye filled with tears. They were safe at last and going home.

Flynn Returns Home

With Stalag VII-A, the last POW camp to be liberated, the American Army now had the job of not only feeding the starving men but providing medical attention, clothing, and transportation and helping the troops of other nations as well.

The next day, April 30, Hitler committed suicide. General Patton arrived at the camp on May 1, where he spoke briefly to the men and shook a few hands.

Lieutenant Flynn was one of the first officers to be interviewed at Moosburg by Army Field Historian Captain William K. Dunkerly about the Battle of the Bulge and how he and the other POWs were treated during their captivity. These interviews are housed in the National Archives.

Flynn then had his first plane ride in a C-47 on May 7, en route to the 195th General Hospital outside of Paris. Six days later, Flynn boarded the merchant ship John Erisco and sailed for New York. From there he would go to his oldest brother Bill’s place in Chicago.

Anna received a telegram from the War Department on May 21 telling her that her husband had been liberated from a POW camp. Without telling anyone, or turning in her resignation at the hospital where she was working, Anna immediately packed her bags and left Minnesota to meet her husband in Chicago.

As they entered New York harbor, Flynn watched eagerly as the ship passed all of the familiar landmarks of home. Later that evening he walked in the door of his mother’s Manhattan apartment, and the next day he caught the train to Chicago, where Anna was waiting for him.

Flynn was awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart with Oakleaf Cluster for his actions in the Hürtgen Forest and the Battle of the Bulge and promoted to captain. He was honorably discharged in January 1946 and attended Iowa State University on the GI Bill while his wife worked as an RN at a local hospital.

He graduated with a degree in veterinary medicine in 1950 and established his practice in Anna’s hometown of Kimballton, Iowa. Tom and Anna raised eight children, seven of whom earned college degrees and one who served four years in the Air Force. Tom Flynn was very involved in the town’s civic activities and with the Kimballton Volunteer Fire Department, serving 41 years as a fire fighter, 27 years as chief.

Thomas Flynn passed away in November 1993. The following year, the Kimballton Fire Department honored Tom’s memory and dedication to serving the community by having his name inscribed on the Iowa Firefighters Memorial in Coralville, Iowa.

Capt. Fred Feiker was my Uncle ( My Mother’s Brother) I am now 85 and have been trying to learn all I can about Fred .I plan to visit his grave in St Avold,France (Military Cemetery). If you have any info about Fred please email me .. Ket Weist

Dear sir,

I live in the south of Holland so for me (us) the Ardennes, Luxemburg is a two hour’s drive. I own a Willys MB jeep dated1943 . Although she is was in a very mind state when she ( it?, he?) arrived from the US it took me five years to restore the jeep.

I visit the viscinity of the northern part of Luxemburg often, the towns of Marnach, Clerveaux and Hosingen. With my family we visit a campsite near Obereisenbach in the Our-valley, 4 miles to the east of Hosingen. It is here where the German forces came out of the valley to march in the direction of their objective Bastogne. At a crossroads of Hosingen itself is a little forrest, I tried my luck en went in with a metaldetector. Only e few metres next to the road my detector (and it’s a very cheap one, hahaha) found some metal…..just poking into the ground with a knife and hands I found pieces of munition, both german and American. History is not far away. To me it’s a kind of holy ground, in about two weeks I’ll drive my jeep around Hosingen, Marnach and Clervaux. The world knows about the Battle of The Bulge, about the actions of 101 airborne and Patton saving Bastogne……but the battle wasn’t won in Bastogne, or by the ‘Eagles’ or by Patton. It was won in little villages like Marnach, Hosingen and Clerveaux in those first ours of the offensive, it was won by the 28 ID, by the 110 IR. Kind regards from Holland, hope you are well and a nice Christmas! Jos Helgers

Mr. Weist,

My dad James Morse was one of the Hosingen defenders in the first days of the Battle of the Bulge, Dec 16-18, 1944. Alice Flynn has written a wonderful book about that defense, and their ultimate capture and months as German POWs. The title is “The Heroes of Hosingen,” and I highly recommend it if you haven’t already read it.

My dad knew your uncle well, and liked him. In an interview with another writer, more than 50 years after the battle, he wrote:

“I had a long time relationship with Capt. Feiker, in training and in battle (frequently supporting his Company with 81mm mortar fire, and when no artillery observer present, directing artillery fire). He was a fine gentleman, capable, cool under fire and very intelligent; an exceptional company commander.”

If you’d like to discuss further, you could email me at mthorebian@gmail.com