By Allyn Vannoy

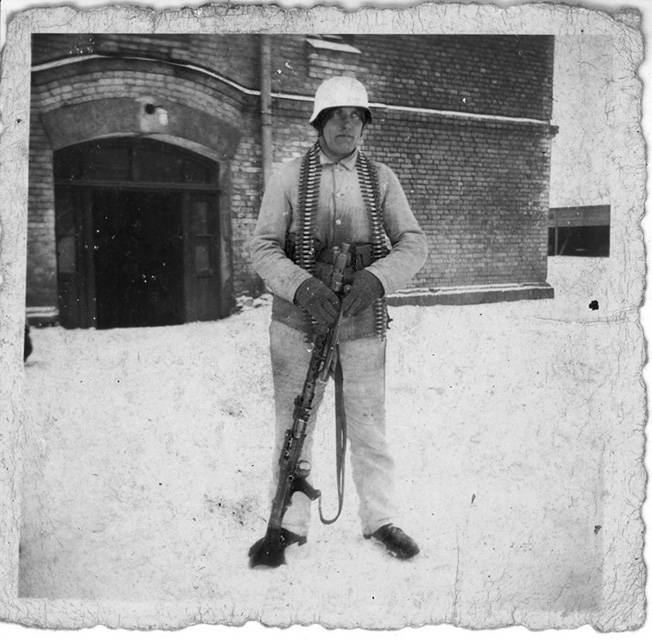

As Russian and German tanks exchanged fire, German Corporal Erwin Engler realized that if he was to get his wound treated, to even survive—if he was to ever see his family again back in what had been the Polish Corridor—he was going to have to make a dash across open ground to reach the safety of a wooded area. It was March 1944 in the Ukraine, and the Third Reich was in retreat.

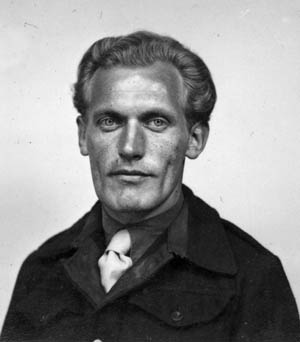

Erwin Paul Engler, born on March 1, 1922, was an ethnic German living in pre-war Poland. From 1941 to 1948 he was transformed from a cabinetmaker’s apprentice into a wounded and decorated veteran of the Wehrmacht and would be a prisoner for three years after the war’s end. His family would face the loss of its home, forced labor, and finally, banishment from their homeland. His son Peter talks about his father’s experiences.

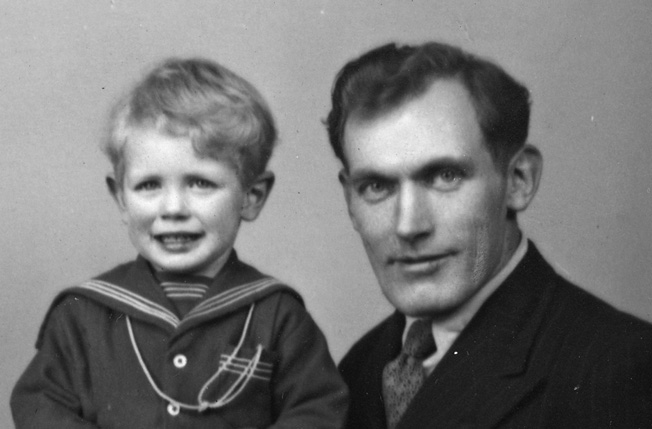

“Erwin Paul Engler, my father, was a caring man, and, over time, he shared some of his wartime experiences with my sister and me. We were then living in England. When I was six years old, our English mother deserted us and Dad, though residing in a foreign country, resolved that he would bring my sister, then age four, and me, up on his own—despite the difficulties he faced. I did not see my mum again for 20 years. Dad was nurturing, saw to our education, and provided us with our sense of values. Being without a mother actually had a far greater impact on me than being half German growing up in postwar Britain.

“As we got older, Dad would tell us his recollections of growing up in his hometown in Poland and his life as a German soldier and as a prisoner of war. He grieved over the death of his mother and aunt in a Polish camp in 1947.

“In our small English town of 4,000, my father earned a reputation as a reliable and a skilled craftsman or wood joiner. Most people judged him by his deeds, not by his ethnicity.

“Dad told us of his family history. As I grew up I wanted to know more about my heritage and read up on German and, more specifically, Prussian history. I also read Polish history and reflected on how the two ethnic groups coexisted for so many centuries.

“It was while researching the family history and translating letters from my German relatives that had been interned in Poland after the war that I became aware of the Polish-German reconciliation efforts in Potulice, Poland, the site of my grandmother’s death. A memorial to German victims was built near the memorial to Polish victims.

“I decided to travel to Potulice in memory of my grandmother and there I met the Polish members of the reconciliation movement. It was during the trip that I was able to put my father’s ghosts to rest—he had died five years earlier. I believe that such a trip might have helped him to find closure to the postwar issues he struggled with.

“Knowing that my dad had fought on the Russian Front fed my own fascination with the subject. Eventually, I gained a greater understanding of the futility of the German war effort and Dad’s comments about it being a ‘meat grinder.’ At the same time, Dad became more open about his experiences.

“On his last visit to my home in Australia, he dictated details that I had never heard before. He provided facsimiles of his decorations. This was so out of character from my earlier memories of him, but I was pleased to have them and the new information. Maybe he had sensed his end was nigh, or maybe the family research I had done showed him I really was interested. Whatever the reason, I was glad to have the memoirs, which I was able to build on later.

“I owe my personal success to him. Given our family hardships and economic difficulties in Britain in the decade after the war, my sister and I could easily have been put into an orphanage at a time when many children, not necessarily orphans, were being sent to be adopted by families in Canada or Australia. He could have insisted that we leave school at age 15 to make his life easier, but he wanted us to have the chance he never had. To him, education was all important.

“He was one of many good men on both sides who were engulfed by the war. The fact is that Dad was obliged to do his duty, and even though he was fighting for a vile regime, a soldier must fight to survive.

“Because he possessed character and a determination to do any job he set his mind to, I assume he was a good soldier as well. He also possessed a certain degree of luck, but he called upon his experience to get himself out of many sticky situations. He was part of a defeated army, but he never complained or considered the ‘what ifs.’ Letters from the time he was a prisoner reflected this acceptance.

“What hurt him most was that his family paid the ultimate price for the Nazi regime’s excesses and history’s ignoring the fate of both ethnic and national Germans in Eastern Europe.”

A Volksdeutscher in WWII

Erwin Paul Engler was born in the town of Schöneck (the present-day Polish town of Skarszewy) in what was the Polish Corridor—between East Prussia and Germany proper—and 40 kilometers south of Danzig (present-day Gdansk), the capital of the former German province of West Prussia. The area had been ceded from Germany in 1919 as part of a reconstituted Poland, under the terms of the Versailles Treaty. As a result, Engler, though an ethnic German, was a Polish citizen—considered a “Volksdeutscher” by the German Fatherland.

Volksdeutsche was a term that the pre-World War II German government used to describe ethnic Germans living outside or, more precisely, born outside the Reich, in contrast to Reichsdeutsche (Imperial Germans) or Germans living inside Germany proper. Under the Nazis, Volksdeutsche was used to describe ethnic Germans living outside the country without German citizenship.

According to 1930s estimates, there were about 30 million Volksdeutsche and Auslandsdeutsche (German citizens living abroad) beyond the Reich. Other sources estimated the number of ethnic Germans in Central and Eastern Europe at 10 million. A significant proportion of these were in Russia, Poland, the Ukraine, the Baltic States, Romania, Hungary, and Yugoslavia. Many of them could trace their family to ancestors who had migrated to Eastern Europe in the 18th century, invited by governments that wanted to repopulate areas decimated by disease and by the Ottoman Empire.

The Volksdeutsche’s Special Role in German Expansion

The Nazi goal of expansion to the East gave the Volksdeutsche a special role in German plans as well as propaganda—to give these people German citizenship and elevate them in status above the native populations. German nationalists used the existence of these large German minorities in Eastern Europe as a basis for territorial claims. Much of the propaganda of the Nazi regime against Czechoslovakia and Poland claimed that ethnic Germans in those countries were being persecuted.

As Nazi Germany invaded Czechoslovakia, Poland, and other European nations, members of the ethnic German minorities in those countries aided the invading forces and the subsequent Nazi occupation. These acts resulted in increased enmity against the Volksdeutsche.

Some of the Polish Volksdeutsche belonged to such groups as Deutscher Volksverband and Jungdeutscher Partei, groups opposing coexistence with the Polish state. Any ethnic Germans who did not act in the proper manner were branded as traitors by these organizations. An estimated 25 percent of the ethnic German population in Poland belonged to Nazi-sponsored organizations supporting the Nazi conquest of Poland. German nationalist organizations in Poland and Czechoslovakia were reputed to be carrying out acts of sabotage against the local population.

As the Nazis moved into Eastern Europe the Volksdeutsche were taken into the Wehrmacht or Waffen-SS, impacting feelings toward the ethnic Germans. In Yugoslavia, the Waffen-SS Prinz Eugen Division was formed from local Germans; it garnered an infamous reputation for its brutal operations carried out against partisans and suppression of the local population. About 300,000 Volksdeutsche from Nazi-conquered lands and satellite countries joined the Waffen-SS. In Hungary alone some 100,000 ethnic Germans volunteered for German military service.

The Deutsche Volksliste

After defeating the Poles, the Nazis annexed the former areas of the old German Empire into the Greater Reich. Volksdeutsche in these annexed areas numbered 2.7 million, with another 120,000 in the area of the General Government—the remainder of occupied Poland.

Following the occupation of western Poland, the Nazi authorities created the Deutsche Volksliste (German Peoples’ List)—a bureau to register Polish citizens of German ethnicity as Volksdeutsche. The German authorities encouraged such registration, in many cases either forcing it upon the population or terrorizing Polish Germans if they refused to register.

Polish citizens of German ancestry were confronted with a dilemma—register and be regarded as turncoats by their fellow Poles or not sign up and be treated by the Nazi occupation forces as traitors to the German race. Those who registered were given benefits such as better food and increased social status. In addition, there was large-scale looting of property and redistribution of goods to the Volksdeutsche—providing them with apartments, workshops, farms, furniture, and clothing confiscated from Jews and Poles. In turn, thousands of Volksdeutsche joined the German armed forces either voluntarily or through conscription.

Conscripted Into the Wehrmacht

Following completion of an apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker in early 1941, Erwin Engler was called upon to serve in the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD, Reich Labor Service), an auxiliary organization that supported the Wehrmacht by carrying out construction and transport projects. From February to June 1941, his RAD unit served in Poland. After the invasion of the Soviet Union, it was sent to Russia from July through November 1941, building barracks and working on runways for the Luftwaffe near Minsk and Smolensk.

In November 1941, the young Engler returned home and was conscripted into the Wehrmacht on December 6, 1941, receiving training at Suwalken, East Prussia (Suwalki, Poland) to operate a machine gun until early February 1942. An amused Engler recalled, “I held the record at training for firing off the least number of rounds.”

After completing training, he was sent as a replacement to the Russian Front, reaching the 519th Infantry Regiment, 296th Infantry Division north of the city of Orel and southwest of Moscow later in February.

The division to which he was assigned had served in France in May 1940 but had seen no serious action there. From the summer of 1940 to the spring of 1941 it was stationed near Dunkirk before being transferred to Army Group Center for Operation Barbarrosa, Germany’s surprise invasion of the Soviet Union. The 296th Division was heavily engaged in fighting near Moscow in late 1941 and early 1942. By the time Engler reached the division, the initial Russian winter counteroffensive in that area had ended, and fighting in the 296th’s sector had settled into one of static warfare.

Engler quickly became savvy to the cruelty of the war that was being fought on the Russian Front. “I always saved one hand grenade in case a Russian tank was about to run over me,” he related.

Wounded on the Eastern Front

After four months of frontline duty, on July 7, 1942, a mortar round exploded in front of Engler, resulting in wounds to his stomach, to his right side (behind the liver), and in the right shoulder. Following six weeks in a field hospital in Orel, he was transferred to an army hospital at Vienna for 61/2 months of treatment and recovery. Engler recalled, “The shell splinters were never removed from my side or shoulder, troubling me in later life.” For his wounds he was awarded the Schwarze Verwundeteabzeichen (Black Wound Badge).

After being discharged from the hospital, he was sent to an army camp at Budweis (Ceské Budejovice), Czechoslovakia. To rehabilitate his arm, he forced himself to peel potatoes and cut the bread for the entire camp. In May 1943, the Wehrmacht classified him as “KVI” or Kriegsversehrtestufe I (War Disabled Level 1)—a classification given to soldiers considered unfit for combat. Those classified as Level 2 were considered too disabled for further duty and were discharged from the army. He was also promoted to lance corporal.

In June 1943, Engler was transferred to a battalion guarding prisoners of war at Brüx (Most), Czechoslovakia. For four months he served as a guard for French prisoners.

Five months later, in November, due to manpower shortages the KVI classification for wounded soldiers was abolished and Engler was declared fit for frontline duty. He spent the next four weeks in a refresher program at a training facility at Bayreuth, Germany, north of Nuremberg.

Engler’s Guardian Angel

Engler was not the only member of his family in the army. His cousin was reported missing at Stalingrad and his brother was shot through the elbow at Leningrad and was invalided out of the army. But he believed that he had a guardian angel watching over him. “I was walking with two comrades and a Russian bomber attacked,” he said. “I hit the ground and a bomb exploded in front of us. When I got up, my two comrades had vanished.” In addition, he recalled, “I was the only boy from my class who survived the war.”

In January 1944, he was assigned to the 326th Infantry Regiment, 198th Infantry Division, as the unit was on its way to Uman, in the heart of the Ukraine.

In action for the next three weeks, his unit found itself alternately fighting one day and retreating the next. Besides facing a Russian winter offensive, Engler would recall years later, “You don’t know what cold is until you’ve had to survive -40 degrees of frost without a roof over your head!”

On March 5, 1944, the Russians launched a massive attack along the front, annihilating Engler’s regiment. He was wounded as a bullet grazed his left shoulder blade. He and six comrades took shelter in a village as a tank battle raged around them. With his wound, he knew he had to escape the fighting, realizing that he would receive no medical treatment should the Russians capture him. Despite his comrades’ refusal to follow, he ran through the middle of the tank battle to the safety of some woods. It was four days before he was able make his way back to his lines and get his wound treated.

During his evacuation from the front, he was placed on a train of cattle cars. There he believed that providence intervened. “I was told to get into wagon number seven,” he said, “and as I was about to do so I heard a voice telling me not to get into wagon number seven, so I got into number eight instead. The next morning the train of wounded soldiers was at a siding when it was bombed. Wagon number seven received a direct hit.”

Engler recalled that at one point a Soviet attack resulted in an unusual debt. “I owe my life to a successful counterattack by the SS against a Russian advance that cut the railway line that was taking me to a hospital behind the lines.”

Earning an Iron Cross

He was next sent to another hospital to recover, and in May 1944 was moved to Mühlhausen, Germany. Three months later he was transferred to Münzingen in the Schwarzwald (Black Forest), where the 1121st Grenadier Regiment, 553rd Volksgrenadier Division, was being formed; he was assigned to the Sturm Kompanie (assault company). The 553rd was sent to the Western Front, where it was tasked with defending the French city of Nancy from the Americans in early September 1944.

Upon the regiment’s arrival at Nancy, Engler’s unit was moved to a position along the Moselle River. For the next few weeks it was in constant action against the U.S. 35th and 80th Infantry Divisions as they maneuvered to cut off and surround the city.

As part of the assault company, Engler was sent on raids against American positions near Millery, a few kilometers north of Nancy. During one mission, his unit blew up a bridge over the Moselle, just south of Millery. On another raid, it crossed the Moselle in rubber boats to destroy a canal or river lock behind American lines.

During September 1944, Engler received the Infanteriesturmabzeichen in Silber (Silver Infantry Assault Medal) for action against the Americans. He had qualified for the decoration many times on the Russian Front but had never been recommended for it. He was also awarded the Eisene Kreuz IIe Klasse (Iron Cross Second Class) for bravery near Millery.

Although he was a loyal soldier and fought well, even Engler had his limits. “I could have become a sergeant,” he said, “but I did not want the responsibility of choosing men to go on a patrol which could get them killed.”

Capture by the Allies

On October 8, 1944, while in the village of Jeandelaincourt, east of Millery, Engler encountered Americans advancing on his unit’s position and came to the realization that “it was all over.” In postwar correspondence he indicated that eventual capture was something he’d reckoned with. A short while later he was sitting in a cellar with a comrade, smoking a cigarette, when an American burst in with his weapon at the ready and shouted, “Hands up!” His American captors took everything of value from him, including his watch.

As American POW camps were full, Engler was handed over to the British, and on November 1 was shipped to Southampton, England. He was transferred to the main processing center for prisoners at Devizes, then in turn to Belfast, Liverpool, and Cheltenham. By 1946 he was in Leckhampton, just outside Cheltenham.

conservative. On the whole, German POWs were treated far better by the U.S. and Britain than those captured by the Soviets.

Engler was one of hundreds of thousands of German soldiers captured as the Allies advanced across France and Belgium and into Germany. Plans were to bring many of the prisoners to Britain, where they would remain until Germany’s capitulation. After the failure of the German Ardennes Offensive (Battle of the Bulge), some 250,000 German soldiers surrendered. Then, with the collapse of the Ruhr Pocket another 325,000 were taken prisoner. After Germany’s capitulation, some 3.4 million German soldiers were in Allied custody.

During 1946, Britain held more than 400,000 German prisoners, many of whom had been transferred from camps in the United States and Canada. Thousands would continue to be held for two to three years after the German surrender and used for forced labor, as a form of reparation. The POWs even referred to themselves as “slave labor.” There were reports from Norway and France of many prisoner deaths while clearing minefields.

One report by French authorities stated that in the fall of 1945, 2,000 prisoners per month were being maimed or killed in “accidents.” The issue brought about public debate in Britain and was taken all the way to the House of Commons. In 1947, the Ministry of Agriculture argued against rapid repatriation of German prisoners, as they made up some 25 percent of the agricultural workforce and the Ministry wanted to continue to use them into 1948.

“Disarmed Enemy Forces”

With the German surrender, the Allied leadership became concerned that their former adversaries might decide to conduct a guerrilla-style war against the Allied occupation. The Allied powers had decided at the highest levels to repudiate the Geneva Conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners, the Soviet Union having never signed the Conventions. The Conventions prescribed that POWs were to be sent home within months of the end of fighting.

As soldiers of a state that no longer existed because the Nazi regime had been destroyed and no civilian government was yet in place, the Western Allied command decided to create a new classification for the German prisoners—“Disarmed Enemy Forces,” or DEF. This allowed the Allied armies to forego treating the German soldiers as prisoners of war—they would not be guaranteed the rights of prisoners of war under the Geneva Conventions.

This raised the contention of prisoner protection and welfare—that the creation of the DEF classification was intended to circumvent international laws regarding the handling of POWs, providing a form of reparations to rebuild the damage caused by the war and Nazi actions. The demands of the French government were considered especially compelling, the Germans having held millions of French POWs and civilians as slave laborers.

After Germany’s surrender, as the United States shipped some 740,000 German POWs to France, there were newspaper reports of their poor treatment. In October 1945, Judge Robert H. Jackson, Chief U.S. prosecutor at the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal, complained to President Harry S. Truman that the Allies “have done or are doing some of the very things we are prosecuting the Germans for. The French are so violating the Geneva Convention in the treatment of prisoners of war that our command is taking back prisoners sent to them. We are prosecuting plunder and our allies are practicing it.”

Rheinwiesenlager

Many of the German soldiers captured in the spring and summer of 1945 by the Western Allied armies were interned in Rheinwiesenlager (Rhine meadow camps) or “Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures.” A group of 19 temporary camps was established, holding an estimated 557,000 POWs from April to July 1945. Most of the camps were established west of the Rhine River to prevent prisoners from attempting to rejoin the German armies or organize a resistance.

Plans for the camps called for the use of open farmland close to railroad lines, enclosed with barbed wire and divided into 10 to 20 camps each housing 5,000 to 10,000 prisoners. Some of the camps quickly became overcrowded. For example, Camp Remagen, intended for 100,000, grew to a population of 184,000 prisoners.

The Americans transferred internal operations of the camps to the German prisoners themselves. Camp administration, police and law enforcement, medical, food preparation, and assigning of work details were all managed by the prisoners.

After screening to detain Nazi Party members for possible prosecution, initial prisoner releases included those who were regarded as harmless—women, old men, and boys of the Volkssturm. Later, those professional groups considered needed for reconstruction as well as farmers, truck drivers, and miners were released. By the end of June 1945, the first of the camps—Remagan, Böhl-Ingelheim, and Büderich—had been closed. Then prisoner releases were halted. On July 10, 1945, eight camps with some 182,400 prisoners were transferred to French control. Those prisoners who were considered able to work were transferred to France, and the rest were released.

Under the Geneva Convention, German POWs were to receive the same ration as their Allied captors. Instead, designated as “Disarmed Enemy Forces,” they got no more than German civilians. Given the situation in Europe from April to July 1945, this meant starvation-level rations, though enough food was provided to prevent mass famine.

Estimates of deaths among prisoners in the Rheinwiesenlager camps ranged from 3,000 (U.S. figures) to 10,000, due to starvation, dehydration, and exposure. Most of the deaths were attributed to the unexpectedly large number of POWs that suddenly came into Allied hands at the end of hostilities.

Reasons given for the poor treatment of some of the German POWs included the indifference, even hostility, of some U.S. guards and camp officers. Revelations of starved inmates and evidence of the mass murder found in recently liberated Nazi death camps provoked distain, if not outright hatred, toward the Germans. Some senior Allied leaders thought the Germans deserved to experience the hunger they had imposed on others.

General Lucius D. Clay, deputy to General Eisenhower in 1945 and then Deputy Governor of Germany under the Allied Military Government, stated on June 29, 1945, “I feel that the Germans should suffer from hunger and from cold as I believe such suffering is necessary to make them realize the consequences of a war which they caused.”

Europe in Crisis

All of Europe faced dire conditions following the end of the war for a variety of reasons. The collapse of Germany in the spring of 1945 was also an economic collapse, especially of food production. Nitrogen and phosphates needed for fertilizer had been diverted to weapons production since 1943. German rail transportation and food production facilities had suffered heavy bomb damage.

In addition, Hitler did not want the German people to survive his defeat and gave orders that scorched earth operations be conducted—though with limited results. The slave laborers who had maintained German agriculture had departed with few returning Germans to replace them. Tribute and goods seized from occupied territories were no longer available. The Russians also blocked the flow of agricultural surplus from eastern Germany to the west. Even “displaced persons” (DPs), victims of Nazi deportation and slave labor (seven million in Germany, 1.6 million in Austria), were on short rations despite the sympathy and efforts of Allied authorities.

At the time of Engler’s capture in 1944, his family and relatives, including his mother, father, two brothers, an uncle, two aunts, and two cousins, were still living in and around their village of Schöneck.

Fate of the Volksdeutsche at Potsdam

While Engler was a prisoner in Britain, the Allies were making plans for what to do with his former home in Poland and for postwar Germany.

A decision to shift Poland’s postwar boundary westward was made by the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, having learned the hard way about the use of ethnic bloodlines as a justification for Nazi Germany to expand its borders and invade its neighbors. The precise location of the border was left open, the Western Allies having accepted in principle the Oder River as the future western border of Poland.

The result of the Potsdam Conference, July-August 1945, was to transfer 112,000 square kilometers of former German territory to Poland while also transferring 187,000 square kilometers of former Polish territory to the Soviet Union. The northeastern third of East Prussia was annexed by the Soviet Union, creating Kaliningrad Oblast.

It was also decided at Potsdam that all ethnic Germans remaining in Polish territories should be expelled to prevent any claims of minority rights or possible land claims by any future German government. The Potsdam provisions prescribed “the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken … in an orderly and humane manner.”

Even British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was convinced that the only way to alleviate tensions after the war was the transfer of people to match the national borders. In a speech before the House of Commons in 1944, he declared, “Expulsion is the method which, insofar as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble…. A clean sweep will be made. I am not alarmed by these transferences, which are more possible in modern conditions.”

There had been German wartime plans for evacuation of civilian populations in areas threatened by Soviet advances—some were prepared well in advance while others had been haphazard or purposely neglected. The evacuation plans for parts of East Prussia were completed and ready for implementation by the middle of 1944.

Despite these preparations, Nazi officials were late in ordering the evacuation of areas close to the front before they were overrun by the Red Army. This was due in part to paranoia regarding the possible consequence of being labeled a defeatist and Hitler’s insistence on holding every foot of ground.

About 50 percent of the Germans residing in areas annexed by Germany during the war and nearly 100 percent of those residing in occupied territory were evacuated. While some 7.5 million Germans were either evacuated or otherwise escaped East Prussia and the occupied territories, many lives were lost because of severe winter conditions, poor evacuation organization, or military operations.

“We Who Have Lost Everything”

As the war had drawn to a close, many Germans had fled before the Russian advance; however, Engler’s parents had decided not to flee because they felt that they had done nothing wrong and naively believed they would be all right. In March-April 1945, their town was occupied by the Red Army, the communist regime interning all ethnic Germans. His family members were subsequently forced to work on farms and in factories, which paid the state, not the individuals, for their labor.

While Engler was in captivity, his hometown came back under Polish control and, apart from his sister, the rest of his family was interned by Soviet authorities. The family’s farm was confiscated, and the family members were forced off the land and into camps.

Concerned about his family’s welfare, Engler asked in a letter to his sister, “Do you by chance know what has happened to our dear mother and the others and where they are now? It would be the greatest joy for me to now find that out. My letters that I have written back home have so far all remained unanswered. I was captured on 8 October 1944 and was brought to England. I am working here on a farm. Health wise I am very good, which I also hope for you.”

Engler was not only a strong individual, having survived several combat wounds, but also exhibited strength of character. In a letter from prison camp to his family in July 1946, he said, “We who have lost everything should realize that our future will not be a bed of roses. Then as long as we don’t also lose the courage to face life, we will pull through, of that I am convinced.”

After the communists took over in Poland, many Polish ex-servicemen chose not to return home and stayed on in Britain. Their presence seemed to make Engler’s life more difficult as he wrote in April 1947: “Unfortunately in the town there are many Polish soldiers and when I see them, the whole Sunday afternoon is ruined.”

During his time as a prisoner in Britain, while working on local farms, Engler earned the respect of those he worked for with his strong work ethic, forming lifelong friendships. And while working German prisoners did receive pay for their labor, it was very little. In July 1947, Engler wrote, “Our POW income is very meagre; we earn 5½ shillings a week. For that we can buy 20 cigarettes and a piece of cake.”

Engler felt that while he and his fellow prisoners were adequately fed, it was torture to arrive at the farm each day to work and see the farmer eating a hearty breakfast of eggs and bacon, which the prisoners did not receive.

Peter Engler recalled his father telling him how as a prisoner he had porridge for breakfast every day, which was unfamiliar to him. To make it more palatable, he would add bits of chocolate to it. Peter said, “Chocolate porridge with cocoa and sugar became a staple in our house as we grew up.”

Nothing to Return to

While a prisoner, Engler’s mother died of pneumonia in a camp near Potulice, Poland, after having been forced to work in the fields while ill. He was also concerned about his 13-year-old brother, Friedel. Engler had heard rumors that the Russians were abducting children and taking them to Russia.

Engler’s surviving relatives were expelled from Poland to Germany during 1948-1950, losing all their property and possessions in the process.

Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans were detained in internment camps or sentenced to forced labor, some of them for years. Even today the expulsions have entered the German vocabulary as “the Flight” or “the Expulsion.” The total number of ethnic Germans living in Eastern Europe today is approximately 2.6 million, just 12 percent of the prewar figure.

Because of actions by some Volksdeutsche and particularly the atrocities committed by the Nazis, the Polish government after the war tried many Volksdeutsche for treason. Even today the word Volksdeutsche is regarded as an insult in Poland.

While a postwar prisoner, there were still rules to be followed, which Engler apparently violated. For that he was given three weeks in the guardhouse.

Toward the end of 1947, Engler was given the opportunity to apply for return to Germany; however, there was nothing to return to. His surviving family members were homeless refugees, having been expelled to Germany.

Many of the ethnic German civilian detainees were held in the same camps that had been built by the Nazis as concentration and death camps. The conditions were abominable, and many perished and were buried in unmarked mass graves.

Taking an English Wife

While working outside his prison camp, Engler met and began dating an English girl. His camp commandant did not approve of the relationship and once told Engler that if he had his way, he would have had Engler transferred to the Shetlands because of his courting the girl.

Nevertheless, the relationship soon flourished. His future father-in-law appealed to the British government and obtained Engler’s release in March 1948, over seven years after being conscripted into the RAD. He later became one of the first released German POWs to take up residence in England. Engler and his English wife would have two children, and he would became a naturalized British citizen in the 1950s.

Engler had fought across Europe—from before Moscow to the steppes of the Ukraine to the Moselle River of France. He carried out his duties and was twice wounded in the process. He considered the war an inglorious waste, believing that it took away seven years of his life fighting for a regime that he felt had treated the German people like so much cannon fodder.

Peter Engler believes his father was “an ordinary soldier faced with extraordinary circumstances, but he demonstrated an important lesson about the measure of a man—it’s not whether you get knocked down, because everyone does from time to time; the measure is in those that get back up.”

Erwin Engler passed away on January 2, 1998, after living a full life during historic times.

Very good article learned new facts

Very good article learned new facts about how the Germans survived

A fascinating story. Many thanks.

Very good article learned new facts about how the Germans survived the war

A wonderful story about the folly of war. Thank you.

Thank you for sharing. Very interesting and educational. Like Mr. Engler, two uncles of mine fought in World War II, in North Africa against the Nazis and Fascists from Catholic Italy. Like millions, they had no inclination for war, were mainly concerned about providing for their own families. But Western Europeans, all professing to be followers of Christ, were for centuries, slaughtering one another resulting in more Christians being killed by fellow Christians than by anyone else. But ask any Christian and he will immediately point to the Muslims. I am NOT a Muslim. It would be interesting to have others comment on this.

A very excellent article. Herr Engler was indeed a fine man, as were many Germans. I lived in Missouri as a young boy during the War. I made the acquaintance of a German POW who worked on a farm. He was even able to have a rifle and hunt game. Many were released during the War in the United States and able to work at various crafts. They were not considered security threats.

His father though, with Gunther Modrow, were responsible for murdering 400 local Poles (priests, teachers, doctors). In 1939, the moment September offensive on Poland was over, Poles were thrown out of homes in that very town, possessions taken, and both Modrow and Engler family benefited. This good soldier benefited from crimes, before he became a good guy. Because of this family, my father grew up as an orphan – his father brutally murdered and possessions stolen, mother died of typhus shortly after. Thanks family Engler and Modrow.

Like Wm. Tecumseh Sherman said; “War is hell!” And WInston Churchill’s admonition; “The only thing worse than winning a war, is losing a war.” War is the distillation of evil.

Very nice article. which speaks good about German people as such.

I am always fascinated by people who try to gain sympathy for their plight but disregard how badly they treated people who were under their control. The Germans were very vicious with their treatment of the French soldiers after France surrendered. There is some comment about it at the end to justify why some European leaders wanted to use German soldiers as slave labor. It should be remembered that Hitler and the Nazis had plans to continue the war after Germany was defeated. Operation Woverine was the code name given to continue the war and it should be noted that there were many incidents of insurgents killing people after the war. I knew of an airman who was a POW and the Germans were given orders to execute them instead of letting them go. He was marched for over sixty miles to get him and his fellow POWs away from advancing soldiers who would have freed him. Poland was treated very poorly during the war and it is understandable that people who served the enemy would be labeled traitors and moved out. I did enjoy reading the story from a different viewpoint. But, I find it hard to feel sorry for people who would have been just fine if Germany had won and had continued to kill Jews and other groups of people. If Germany had won I wonder if the French soldiers would have ever been released.

All that being said Leslie had a comment about Catholic Italy. It should be noted that the Catholic Church saved a great many Jews and did not agree with how Hitler was killing so many people. Christians have not declared war on anyone for hundreds of years. Governments declare wars for political reasons, not religious reasons.

Well – I am quite sure, that my grandfather, local Skarszewy veterinarian and previous honorary mayor was executed by Robert Engler, probably grandfather of the writer. So there is that!

does anyone know if some volksdeusche were also forced labor in pols nines