By Peter Kross

In 1920, a young, handsome Jewish boy from New Jersey took the train from Grand Central Station to Princeton, New Jersey, where he would enroll that fall. The Princeton University that Morris “Moe” Berg attended ran through the quiet Nassau Street, surrounded by the splendid campus buildings and bounded by stately trees that seemed to welcome one and all. This member of the class of ’23 brought a unique blend of brains and brawn to that already well-endowed institution. At the time of his graduation, Moe Berg would be known as a star collegiate baseball player, an expert linguist, and an enigma to all who knew him.

Morris Berg was born in New York into a poor Jewish family of Russian heritage on March 2, 1902. His parents led a simple, middle-class existence. His father Bernard was a druggist, and his mother Rose was a homemaker. Moe had two siblings, a sister Ethel and a brother Samuel. In later years, when he was down on his luck, Moe would move in with one or the other.

When Moe was a young man, the family left its teeming neighborhood on East 121st Street in Manhattan for the greener pastures of Newark, New Jersey. From his home across the Hudson River, young Moe could see the Polo Grounds, the cathedral of baseball that would one day be home to the New York Giants.

In 1906, Moe’s father bought a pharmacy on Warren Street in West Newark. He worked in that location until 1910 and later bought a building at 92 South 13th Street in the Roseville section of Newark. Moe hardly ever worked for his father in the store; instead, he was encouraged to spend his time studying and reading, traits that would endure his entire lifetime.

A Passion For Baseball

Besides studying, young Moe’s passion was baseball. Every time he could, he was seen throwing a baseball on the street, oftentimes with a Newark policeman named Hibler who befriended Moe at a young age. In time, Moe would join the Roseville Methodist Episcopal Church baseball team, much to the chagrin of his father who viewed baseball as a waste of his son’s time and intellect. At age 16, Moe graduated from Barringer High School and, when he was in his senior year, the Newark Star Eagle newspaper selected a nine-man “dream team” with Moe as the third baseman.

After graduating from high school in the spring of 1918, Moe was accepted to New York University at age 16. He played baseball as well as basketball, but only spent two semesters there until he transferred to Princeton in September 1919. At Princeton, Berg studied languages including Spanish, Latin, Greek, Italian, German, and Sanskrit. He played first base and shortstop for the Princeton Tigers and started every game for the team for the next three years. He was never a great hitter, though, batting .235 in his sophomore year and .230 in his junior. In what must have been the thrill of his young life, Moe played for Princeton against Yale at Yankee Stadium on June 26, 1923 (Yale won 5-1). Berg had three hits, including a single and a double.

Moe graduated from Princeton in 1923 with a degree in modern languages. In later years, Ted Lyons, his Chicago White Sox teammate, said of Berg, “He can speak 12 languages, but he can’t hit in any of them.”

On June 27, 1923, following graduation, Moe was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers for the then-handsome annual salary of $5,000, and his dream of playing major league baseball was now a reality. However, his talent on the field was not great; in 49 games at shortstop with the Dodgers, Berg batted just .186. But his educational background quickly attracted the attention of the nation’s sports writers, including Red Smith, who became one of the foremost columnists of the day. After the season ended, Moe packed his bags and left for Paris, France, where he enrolled in the Sorbonne, and delved further into Latin.

Moe’s Baseball Career

In 1924, Moe returned home and resumed playing baseball. To his surprise, he was sent to Toledo in the minor leagues, where he finished the year batting .264. The next year saw Moe playing for the Reading Keys of the International League where he got 200 hits and batted a respectable .311. Due to his superior performance, Moe’s contract was bought for the 1926 season for $50,000 by the Chicago White Sox. Instead of donning his uniform, he chose to attend Columbia University Law School. Thanks to contacts he made, Moe was able to complete his studies while also playing ball.

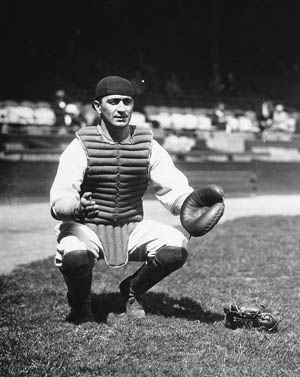

While with the White Sox, Moe played catcher, a position he played for the rest of his baseball days. Casey Stengel observed of Moe, “Now, I’ll tell ya. I mean Moe Berg was as smart a ball player as ever came along. Knew the legs wouldn’t cooperate in the infield and when the catching job opened up, he grabs a mask and puts it on and there he was. Guy never caught in his life and then goes behind the plate like Mickey Cochran. Now that’s something. But I’ll tell ya again, nobody ever knew his life’s history. I call him the mystery catcher. Strangest fellah who ever put on a uniform.” The normally loquacious Stengel of later years was for once, right on the money.

Moe Berg Goes to Tokyo

After an injury, Berg was sent to the Cleveland Indians and later spent time in the Washington Senators organization. In October 1934, he, along with an all-star American baseball team whose members consisted of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmy Foxx, “Lefty” Gomez, and others, boarded the liner RMS Empress of Japan in British Columbia bound for Japan. Why Moe Berg was selected to join this rarified company is a question in itself, one that still has no concrete answer. Unlike the other members of the team, Berg was no superstar. In actuality, he was nothing more than a mediocre player—albeit one with enormous talent that still had not been properly harvested. Is it possible that because of his language skills he was chosen to go along on the trip as an interpreter on some secret, government assignment? The jury is still out on that one.

The Americans were to play a round of exhibition games against the best of the Japanese players, but what Moe Berg carried in his valise was a letter addressed to the U.S. Consulate in Tokyo, instructing them to provide “Mr. Berg such courtesies and assistance as you may be able to render consistent with your official duties.” The letter was signed by Cordell Hull, Secretary of State.

During the team’s stay in Tokyo, Berg took part in all the official functions, holding forth his legendary intellectual prowess on the field and off. He even had time to lecture at one of Tokyo’s major universities, but what Moe understood better than the other American baseball players who accompanied him on the trip was that that the Far Eastern nation was bent on more than just learning the fundamentals of baseball.

Photos For the Doolittle Raid

The Japan of the early 1930s had its foreign policy sights on territories well beyond its borders. Japan, then as now, was wholly dependent for its fuel on outside sources—mainly the oil fields of the Middle East and to a lesser extent, its neighbors in Asia. Japan, like the newly awakening Germany under Adolf Hitler, decided that it needed more living space and, in 1932, invaded Manchuria, its first step toward conquering all of Asia.

The United States was still nine years away from Pearl Harbor, and it would be another seven years before Hitler invaded Poland, touching off World War II. In those intervening years, Washington realized that it needed intelligence concerning future Japanese moves.

After playing a game at the Omiya Grounds near Tokyo, Moe Berg quietly slipped away from the stadium and made his way to St. Luke’s International Hospital. Berg had a cover story on hand as he entered the hospital. He inquired as to the room of Elizabeth Lyon, the daughter of U.S. Ambassador Joseph Grew, who had just given birth. With flowers in hand, Moe made his way toward her room, but along the route he slipped out and climbed up to the hospital’s roof, which had a commanding view of the city. Taking out his movie camera, Moe took pictures of Tokyo, including strategic sites as well as commercial and industrial centers and the naval base in Tokyo Bay. Berg never did meet with Ambassador Grew’s daughter. Just as soon as he reentered the hospital, he quietly returned to his teammates.

Approximately seven and a half years later, military intelligence removed Berg’s films from their resting place. Initially employed in the preparation of General Jimmy Doolittle’s attack on the Japanese mainland from the carrier USS Hornet, they were among the chief photographs used to prepare planners and air crewmen for the massive raids against Tokyo in World War II.

Working With the OSS

The last few years of Berg’s baseball career saw Moe playing for the Cleveland Indians, Washington Senators, and Boston Red Sox.

Shortly before his retirement from baseball, Moe Berg had been corresponding with 32-year-old Nelson Rockefeller, who headed the Office of Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. By June 1941, Berg had been introduced to Rockefeller’s office by a friend named Enrique Lopez-Herrate, a Guatemalan diplomat. While contemplating working for Rockefeller, Berg tried to get the FBI to hire him but was turned down. Berg officially signed on with Rockefeller on January 5, 1942, for the paltry salary of $22.22 per day. His supposed mission was to travel to Latin America as a special consultant to monitor the health of the American military and to extol the merits of physical fitness.

Moe met with both military and civilian officials in Brazil, Panama, and Peru. Later, when Berg began his work for the OSS (the Office of Strategic Services, America’s fledgling intelligence service which was headed by William “Wild Bill” Donovan), he brought with him a letter from Rockefeller explaining that “he had been on a confidential mission for the White House.” Commander R. Davis Halliwell, the chief of the Special Operations Branch of the OSS, said of Berg’s trip to Latin America, “It is evident from Mr. Berg’s conversation with me that his mission for the White House indicated that considerable responsibility had been placed on him and that he was entrusted with a most confidential mission since he was last in this office.”

Returning to Washington after his Latin American sojourn, Berg found himself with little to do. While he waited for his new assignment, he was asked by the OSS to make a broadcast to the Japanese people. In his short wave address he talked about the long-time bond of friendship between America and Japan and said, “I ask you, what sound basis is there for enmity between two peoples who enjoy the same national sport?” Unfortunately, his words had no resonance with the leaders in Tokyo.

In the off-season, Berg worked for a Wall Street brokerage firm, a job that failed to capture his imagination. An unexpected knee injury cut Berg’s playing time, and when he finally hung up his spikes at age 37, he had accumulated 441 hits in 1,812 at-bats, hit only six home runs, and had 206 runs batted in. Berg ended his baseball career with Boston while, at the same time, managing to earn his law degree from Columbia University.

Official Entrance Into the OSS

Moe left baseball, the game he truly loved, on January 14, 1942, the same day his beloved father Bernard died. It was a bittersweet time for Moe, leaving one profession and not knowing what was ahead for him. But, as fate would have it, events a world away would plunge Berg into a new profession, one that he never saw coming, that of a spy for the United States of America.

On July 17, 1942, Seymour Houghton of the OSS thanked Berg “for making it possible to view your film [the one Moe shot from on the roof of St. Luke’s International Hospital in Tokyo in 1934] and for your untiring efforts during the screening of it. Mr. John F. Langan, a member of our staff, reports your film to be of strategic importance.”

Shortly after he left the Office of Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, Berg was officially recruited by the Office of Strategic Services. The man who signed up Berg was Colonel Ellery Huntington, a partner in the Wall Street law firm of Satterlee and Canfield. Huntington was also a personal friend of William Donovan.

Huntington, who served as the deputy director of operations at OSS, wrote a letter to Commander R. Davis Halliwell in which he said of Berg, “ I can vouch for his capabilities. He would make a good operations officer, either here or in the field.”

Berg officially signed on with the OSS at a salary of $3,800 per year and waited for his new assignment. The OSS did not know at first what to do with him, and its records say of Berg’s time in limbo, “It was believed best to keep Berg’s assignment somewhat amorphous.”

After completing his basic OSS training, Berg was stationed in the United States, doing routine work. One of his first assignments was to follow the movements of the exiled King Peter of Yugoslavia, who was now a student at Cambridge University. He also followed intelligence reports from the Balkans and checked on people from the Slavic-American community who had been accepted into the OSS.

Tracking Down the Nazi Nuclear Scientists

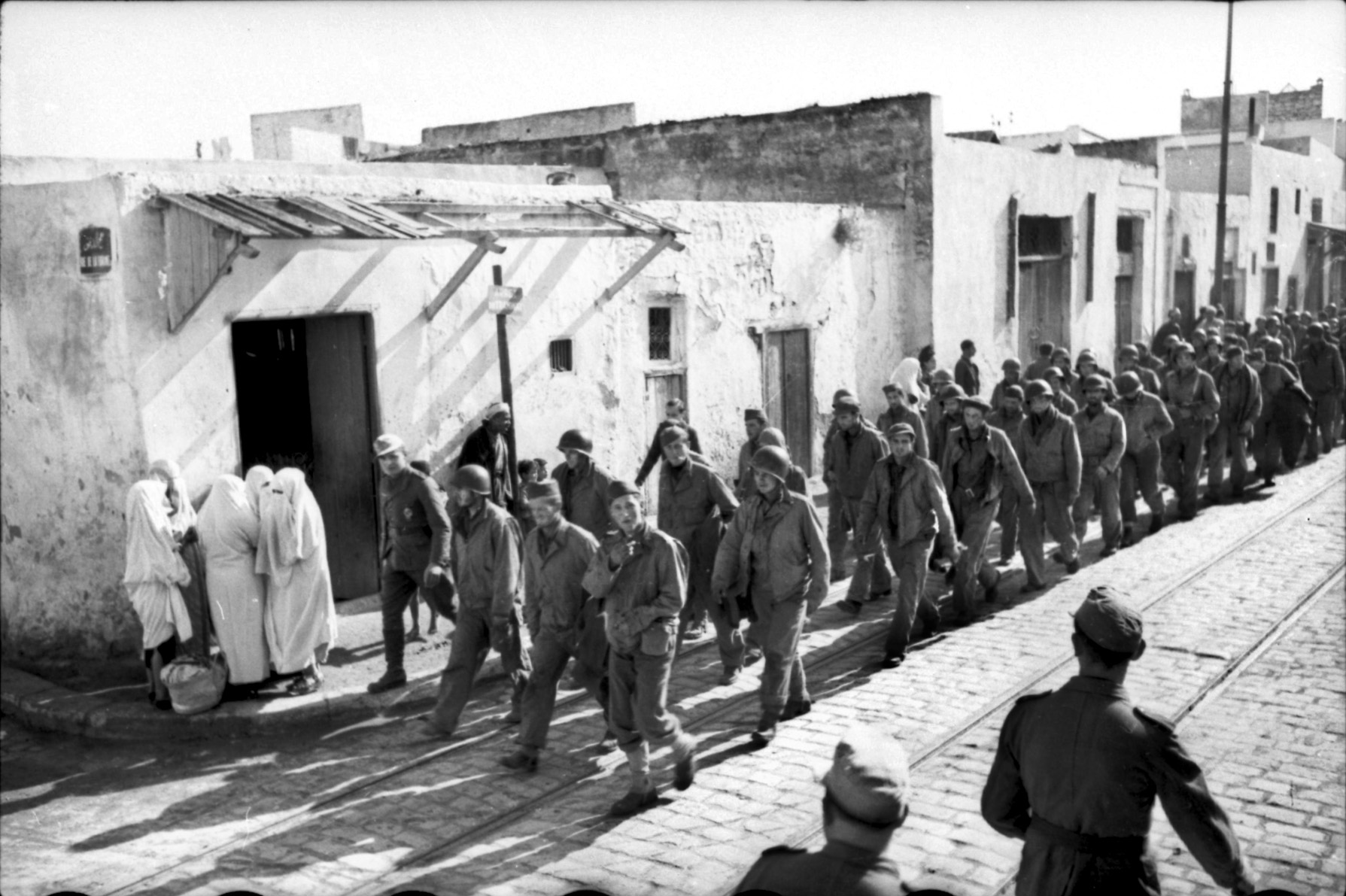

Soon, though, his fortunes would turn, and by April 1944, Berg had been assigned as an agent in the Special Operations Branch where his travel was secret, his expenses were to be paid out of special funds, and he was authorized to carry a .45-caliber pistol and accessories and other special OSS equipment. Berg flew to Italy, Portugal, and Algiers on a mission that involved American interest in possible German development of an atomic bomb.

As Berg flew east across the Atlantic, neither he nor the majority of the American people knew that the United States was developing its own atomic bomb. Knowledge of this super-secret endeavor, called the Manhattan Project, was even withheld from Vice President Harry Truman.

Major General Leslie Groves, military director of the Manhattan Project, was looking for the best agents he could find, and he hired Berg to serve as an undercover operative to track down Nazi scientists who were developing a similar weapon.

Berg was given the code name Remus, was dispatched by his immediate boss Robert Furman to Italy on a submarine borrowed by the U.S. from the Italian Navy in Brindisi. For his own protection, Berg carried a Bersher 7.65mm automatic; he never had to use it. Furman sent Berg to Florence to investigate the Galileo Laboratory where Italian scientists were working on developing long-range missiles.

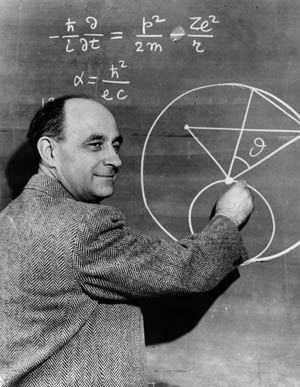

Berg also contacted Italian scientists to find out anything he could on the development of radar and jet propulsion engines. However, this was just a cover mission in case anyone was interested in Berg’s activities. His real assignment, on direct orders from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was to bring any willing Italian scientists back to the United States. He persuaded physicist Enrico Fermi to leave Italy. Fermi later contributed to the development of the U.S. atomic bomb. When Fermi arrived in the United States, Roosevelt said, “I see that Moe Berg is still catching pretty well.”

The Italian project that Berg was assigned to was given the code name Project Larson, which was an OSS operation headed by John Shaheen, head of the department’s Special Projects Division. Project Larsson, however, was just a subterfuge. Its real purpose was to determine what Italian scientists knew about two top German scientists: Werner Heisenberg and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker.

To prepare for his mission, Berg consulted with the top American scientists who were knowledgeable in physics, quantum theory, and electronics. He read all he could on the subjects and talked with such eminent authorities as William Fowler, a Cal Tech Nobel Prize-winning physicist, and Dr. Vannevar Bush, chief of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research.

To Kill or Not to Kill Werner Heisenberg

Werner Heisenberg was the most prominent German physicist of the day, and it was widely believed by the OSS that he had made significant advances in the development of a German atomic weapon. To stop Germany’s progress, the OSS hatched a plot to kill Heisenberg. The operation began in October 1942 and ended in December 1944 when it was no longer considered prudent to continue.

As time went on, a scheme was hatched to kidnap Heisenberg. The plan called for Heisenberg to be taken from Germany to Switzerland, then by plane across the Mediterranean and dropped by parachute to a waiting American submarine. Dr. Hans Berthe, who helped build the American atomic bomb at Los Alamos, New Mexico, tried to get British intelligence to go for the kidnapping plot but was refused.

Like a scene in a Keystone Kops routine, the Heisenberg operation was canceled but reactivated in the summer of 1944. In December, Berg met with William Casey of the OSS (Casey was later to serve as the head of the CIA under President Ronald Reagan) at Claridge’s Hotel in London and was told by the spymaster that he (Berg) was “going to try to find Heisenberg.” Two days later, Berg left for Paris and then Switzerland. Before leaving, he spent one week being briefed by Major Tony Calvert, an intelligence officer based in London, and by Samuel Goudsmit, a Dutch-born physicist.

The OSS had plans for Berg to enter Switzerland under the cover of “a technical expert who desires to proceed to Switzerland and for a period probably not exceeding two months for possible consultation with well-known Swiss scientists.”

That month, Heisenberg traveled to Zurich to give a talk at the Federal Technical College. Moe Berg was sent to observe the German scientist. If Berg thought that Heisenberg believed Germany was close to building an atomic bomb, Berg was given free rein to kill him.

After watching and listening to Heisenberg, Berg had the chance to meet with him and, following their discussions, he decided not to take Heisenberg’s life. Berg was later to write, “As I listen, I am uncertain what to do.”

In Heisenberg’s War, author Thomas Powers writes, “Heisenberg was quite right when he insisted that a huge effort would be required to build a bomb…. But in Germany the first prerequisite for success was missing—desire for victory. No sense of danger, no optimism that a bomb could be built, no enthusiasm for the effort was ever pressed on authorities by Heisenberg or any other leading German scientist…. But Heisenberg did not simply withhold himself, stand aside, let the project die. He killed it.”

In April 1945, shortly before the war in Europe ended, Berg met with Bill Donovan in Paris, where they both learned of the sudden death of President Roosevelt. Donovan informed Berg that the late president had known about his mission regarding Werner Heisenberg.

A Spy Until the End of His Life

After Germany surrendered, Berg returned to Newark where he moved in with his brother. Berg was informed that he had been awarded the Medal of Merit by the U.S. government for his extraordinary wartime service. For reasons known only to him, he declined to accept it. Berg returned to his prewar habits of attending baseball games and spending endless hours browsing used book stores near his home.

In the late 1950s, Berg continued his covert life working for the CIA and later helped NATO select sites for its intercontinental ballistic missiles. In fact, he continued his undercover work almost until the time of his death.

No longer a young man, Berg never returned to baseball but continued to follow his favorite teams. After a fall at home, he died on May 29, 1972. Shortly before his death in a Newark hospital, Berg asked the attending nurse, “How did the Mets do today?”

His family took Berg’s ashes to Israel for burial. In an act that would have pleased Moe greatly, the place of interment remains a secret.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments