By Arnold Blumberg

“Fighting Joe” Hooker was fighting mad when he summoned his chief of cavalry, Brig. Gen. George Stoneman, to his headquarters at Falmouth, Virginia, on February 26, 1863. “We ought to be invincible, and by God, sir we shall be!” Hooker exclaimed. “You have got to stop these disgraceful cavalry surprises. And by God, sir, if you don’t do it, I give you fair notice; I will relieve the whole of you and take command of the cavalry myself.”

Having lavished much care and consideration, including arms, equipment, horses, training, and better rations, on his horse soldiers since assuming command of the Army of the Potomac in late January, Hooker expected a solid return on his investment. Instead, his mounted arm had just experienced another embarrassing blow, one that not only mortified every member of the newly formed cavalry corps but led Hooker to wonder if his efforts to revive the cavalry service had been in vain.

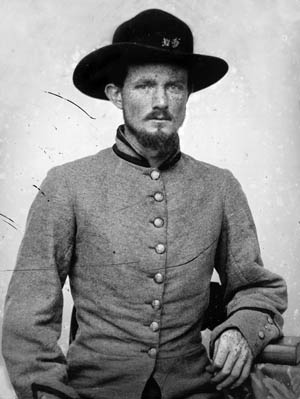

The source of Hooker’s ire was a recent cavalry foray by Confederate Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, Robert E. Lee’s nephew. At Hartwood Church, Lee’s troopers had captured a number of Federal troopers along with their horses and equipment. Making the episode even worse from Hooker’s point of view, Federal pursuit of the Confederate raiders had rapidly degenerated into a comedy of errors that allowed the raiders to escape unharmed.

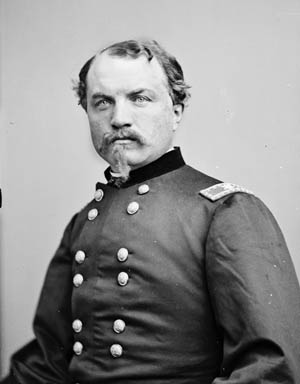

Hooker’s rebuke of Stoneman notwithstanding, the consensus in the Army of the Potomac was that Brig. Gen. William Woods Averell had been the man chiefly responsible for the debacle at Hartwood Church. As head of the 2nd Division of the newly constituted Cavalry Corps, Averell’s command had been tasked with monitoring that part of the Rappahannock River line penetrated by the Rebel raiders. It was his regiments—notably the 3rd and 16th Pennsylvania, 4th New York, and 1st Rhode Island—that broke and ran in the face of the unexpected Confederate attack.

In a subsequent stormy meeting with Hooker, Averell shamefacedly reported on the particulars of the Hartwood episode, as well as a taunting note left behind by Fitzhugh Lee chiding Averell for lax security and suggesting helpfully that the Union brigadier leave Virginia or, failing that, leave a bag of coffee for Lee the next time he fled. Averell, his blood up, requested permission from Hooker to exact revenge for the recent enemy incursion by crossing the river and conducting his own raid. Averell was determined to even the score with his old prewar friend and West Point classmate Fitz Lee and set about planning a mission to do just that. The opportunity for the boiling mad brigadier to implement his scheme was not long in the offing.

Little more than a week after the scuffle at Hartwood, Averell and Stoneman revamped the army’s picket lines to make better use of infantry support and thus decrease the possibility of another unexpected attack by Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s cheeky cavaliers. Officers who had been captured at Hartwood Church had been recommended for dismissal, while noncommissioned prisoners had been reduced to the ranks. Beyond these measures, Averell could do little until the weather cleared. He could not operate south of the river with any confidence on half-frozen roads. The end of February found snow still covering much of the Rappahannock shore. In places where the sunlight beat down on the ground, a trooper in the 8th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry Regiment recalled that the mud was “getting deeper every day.”

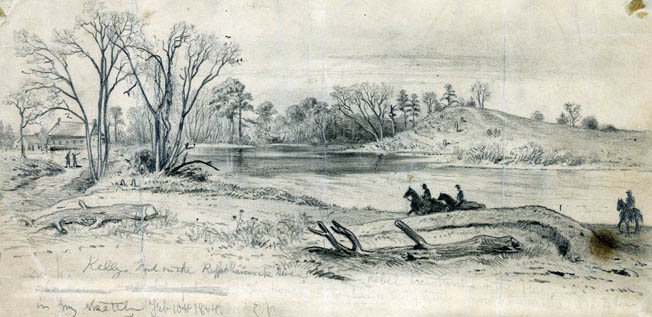

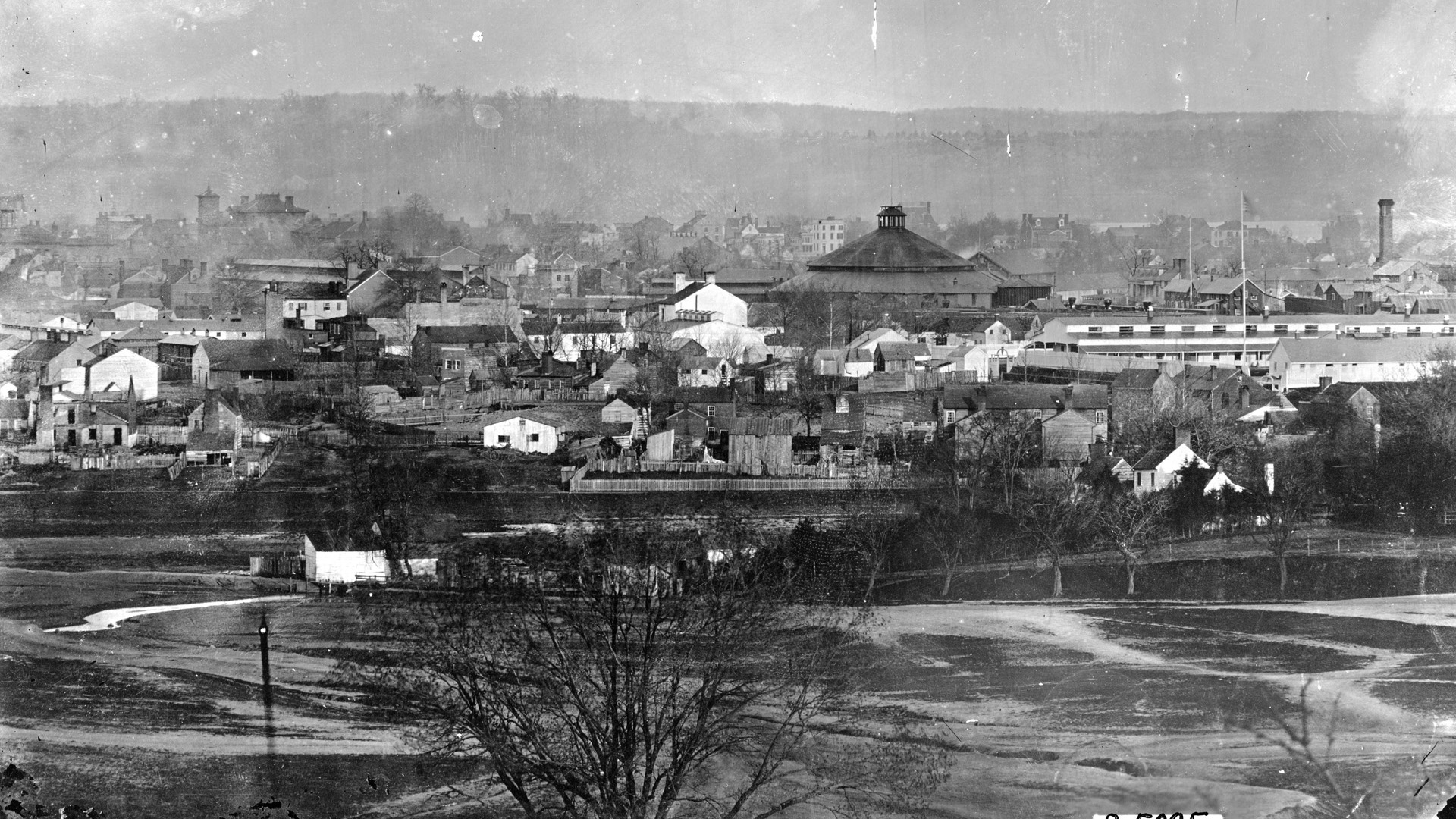

March brought the promise of moderate weather, but not much activity along the army’s front. By midmonth, weather conditions had improved enough for Hooker to plan a retaliatory strike against Stuart. On the 12th he had Stoneman reconnoiter every Rappahannock River crossing between Falmouth and Kelly’s Ford. The scouting mission turned up no Rebels along that stretch of river but did confirm that Fitzhugh Lee’s brigade was camped only 12 miles west of Kelly’s Ford, near Culpeper Court House. Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s horse brigade was thought to be encamped in the same area. Lee appeared to have copied the same mistake Averell had made the month before by setting up a very thin picket line between his camp and the river.

This was all the information Hooker needed. On March 14, he instructed Averell to take 3,000 troopers and a battery of six artillery pieces and destroy “the cavalry forces of the enemy reported to be in the vicinity of Culpeper Court House.” The army commander wanted to test the reaction of his opponent to a Federal crossing of the river. He would use Averell’s raid as sort of a dress rehearsal for his own much anticipated spring offensive.

Assembling at Kelly’s Ford on St. Patrick’s Day

Hooker informed Averell that although Lee’s main body lay at Culpeper Court House, a detachment of between 250 and 1,000 Rebel cavalry, with at least one piece of artillery, was currently active north of the Rappahannock near the town of Manassas. This piece of intelligence would have a significant impact on the forthcoming mission. Averell intended to cross south of the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford. He knew the terrain and that the Kelly’s Ford Road provided the shortest path to the enemy bivouac near Culpeper Court House. He would cross the river there. Normally placid, the water at Kelly’s Ford that March was running unusually fast and deep due to winter rains and melting snow, allowing only one man on horseback to navigate it at a time.

Anticipating a close-quarters fight, Averell ordered his men to sharpen their sabers. He assured his command that they would be victorious in the coming battle. Concerned about the Confederate contingent reported to be north of the river and to his rear near Manassas, he asked Hooker to send a cavalry regiment to Catlett’s Station to cover the Rappahannock fords and picket toward the town of Warrenton. The army commander flatly refused to honor his request, so Averell detached 900 men from the 1st Massachusetts and 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiments to guard against the supposed enemy threat.

Early on the morning of March 16, after drawing one day’s forage for the horses and four days rations for the men, the 2,100-man raiding party rode out of camp at Hartwood Church and advanced 20 miles to Morrisville, reaching the hamlet after dark. The column was composed of Colonel Napoleon Duffie’s 1st Brigade, numbering 775 troopers; Colonel John B. McIntosh’s 2nd Brigade of 565 men; Captain Marcus A. Reno’s Reserve Brigade totaling 760 members, and the 6th New York Light Independent Artillery Battery sporting six 3-inch Ordnance Rifles under Lieutenant George Browne, Jr.

At 1 am on the 17th, the men were roused from their rest and ordered to move out. As the Federals traveled across the countryside, Averell covered his advance with a heavy screen of pickets and sent small parties ahead to observe the roads and fords to mask his approach to Kelly’s Ford. The head of the Union column reached Kelly’s Ford at 8 am. It was Saint Patrick’s Day, and the Union horsemen under Averell intended to celebrate the occasion in high style.

Despite Averell’s precautions during his move to Morrisville, the Confederates knew he was coming. The day before, Robert E. Lee had telegraphed his nephew that “a large body of cavalry has left the Federal army, and is marching up the Rappahannock.” By 6 pm that same day Fitz Lee’s scouts had located Averell’s men near Morrisville. However, Lee still did not know whether the enemy intended to cross at Kelly’s Ford or at Rappahannock Station, four miles farther up the river. Belatedly divining the enemy’s goal, Lee moved to reinforce his 20-man picket party at Kelly’s Ford with 40 more sharpshooters, but only 11 of the newcomers had reached the ford by daylight. In addition, Lee ordered all the regiments of his brigade to send sharpshooters down the road leading from Brandy Station to Kelly’s Ford.

At Kelly’s Ford, the Confederates nervously awaited the Yankees. Meanwhile, they constructed an abatis on the south side bank of the ford and manned rifle pits that had been dug along the shore over the winter. The defenders also occupied two houses that overlooked the ford, as well as a nearby millrace. As Averell neared, the Southerners had only 30 men defending the ford with another 40 troopers five miles to the west where the Orange & Alexandria Railroad and the road to Kelly’s Ford split. Captain James Breckinridge of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry was in charge of the defense.

Deadly Sharpshooters at the Ford

At 8 am Averell’s blue column came within sight of Kelly’s Ford, Duffie’s brigade leading the way. In advance of the column were 100 men from the 4th New York and 5th U.S. Cavalry Regiments whose task was to dash across the ford and capture the Southern pickets on the other side. Covering this move with small-arms fire would be two dismounted squadrons of the 4th New York. The advance guard splashed into the water, which was so high it washed over the backs of their horses, but they were driven back by the fire of the well-protected Confederate sharpshooters on the southern shore. Two more attempts were also repulsed. A member of the 6th Ohio Cavalry Regiment reported, “The [enemy] firing was very sharp and incessant and it seemed as though our men could never cross in the face of that deadly fire.”

A frustrated Averell, seeking to break the deadlock at the ford, sent a small body of men downstream a quarter of a mile to flank the defenders, but the deep water and steep riverbanks foiled the attempt. After 30 minutes of failing to get his men across the river, Averell opted for a more direct way to break the enemy resistance and get his men across the ford. He ordered his chief of staff, Major Samuel Chamberlain of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, to force a passage. The major formed the men of the 4th New York into a column of fours and led them across the Rappahannock, where they immediately ran afoul of the abatis and were peppered by the well-aimed fire of the Confederates in their rifle pits. Southern bullets felled Chamberlain’s horse and wounded the major in the face. Seeing their leader fall into the water, the men of the 4th New York beat a hasty retreat back to the northern bank of the river.

Wounded and exposed to enemy fire, Chamberlain nevertheless called for volunteers with axes to wade the river and dismantle the abatis. Twenty troopers from the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry came forward and, under cover of friendly carbine fire, went to work to destroy the wooden impediment. With Chamberlain leading the way, men from the 4th New York once more plunged into the water and made for the other side but once again were driven back by heavy Confederate rifle fire.

As more Federals dismounted to add covering fire for the axe men working at the abatis, Chamberlain gathered men of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry and directed Lieutenant Simeon A. Brown to “either cross [the river] or not return.” Followed by Chamberlain, the balance of the 1st Rhode Island and the 6th Ohio under Brown sped toward the ford and into a torrent of renewed enemy gunfire. The hail of bullets caused the Rhode Islanders to break and run at the water’s edge, while Chamberlain was wounded a second time, this time in the left cheek. His horse was mortally wounded as its rider fell to the earth. Dragged to the north bank by some of the axe-wielding pioneers, a frustrated Chamberlain first emptied his revolver at the fleeing Rhode Islanders, then turned his gun on the Confederates.

The Rhode Island men soon rallied, and with the 6th Ohio and the pioneers in tow, galloped into the frigid river. Firing their handguns as they rode, the soldiers made it across the Rappahannock and charged at the millrace, causing the Confederate defenders to flee. After a few daring attacks on the Rebel rifle pits, combined with the Southerners running out of ammunition, the Federals took some of the vulnerable places. Seeing no hope for a further defense, Breckinridge escaped. Meanwhile, Lieutenant William A. Moss, commanding Confederate sharpshooters outside the rifle pits, kept up a severe fire on the enemy. However, this did not stop Brown, who was still mounted, from reaching the shore and clearing out some of the rifle pits still held by the Confederates. Brown’s actions not only secured a Union beachhead on the south bank of the ford but also netted him a well-deserved promotion to captain after the battle.

Soon the remainder of the Rhode Islanders crossed the river and broke the Confederate resistance at the ford, capturing 25 of the defenders as they tried to retreat. Over the next two hours the abatis and the road over Kelly’s Ford were cleared of obstacles, allowing Averell’s division to finally cross the river.

Cautious Federal Advance

While giving his men time to water their horses and take a short breather, Averell rode ahead to scout the terrain beyond Kelly’s Ford. He spotted an open plain three-quarters of a mile up the road toward Culpeper Court House near the Wheatley Farm and surmised that it would be there that any future battle with Fitz Lee would occur. The brigadier formed his regiments and at 10:15 am moved forward, leaving one squadron to guard Kelly’s Ford. The blue-clad horsemen rode through the little settlement of Kellysville, consisting of a gristmill and six houses, and followed the road northwest toward the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. Duffie’s men led the way with the 6th Ohio deployed as skirmishers with the 4th New York and 1st Rhode Island following as their support. The column moved slowly and cautiously with scouts investigating every piece of wood they came to. McIntosh formed a line of battle along the woods and along a stone wall, while Reno’s regulars stayed in reserve. All in all it was a cautious advance and missed any opportunity to catch Lee’s regiments isolated and possibly beat them in detail.

As noon approached, Confederate skirmishers in the nearby woods drove back their Union counterparts. In response, Brown brought up an artillery section and shelled the woods. The shelling drove out the enemy from the timber line, allowing Averell’s command to push through the wood and form a battle line in anticipation of an enemy attack. As the Federals cautiously moved forward, they spied Lee’s brigade drawn up for battle on the far side of a wide field.

At 7:30 am, Lee, still at Culpeper, heard that Union cavalry was trying to cross the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford. Lee at once mounted his command, 800 men strong, and trotted off to engage his old friend Averell. His brigade was composed of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiments, supported by a four-gun horse artillery battery under Captain James Breathed. These Virginians, who had humiliated Averell at Hartwood Church, rode to Dean’s Shop, a road junction about 1½ miles from Kelly’s Ford and three miles from Brandy Station, a stop on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. After sending his supply wagons and disabled mounts back to Rapidan Station, Lee eagerly awaited Averell’s arrival.

Following in Lee’s wake was Jeb Stuart. The Southern cavalry leader, who had gone to Culpeper to preside over court marital proceedings for one of his officers, heard the firing coming from the Federals’ attempts to cross Kelly’s Ford. With Stuart rode Major John Pelham, his 24-year-old chief of horse artillery. In his report concerning the battle, Stuart wrote later that “having approved of Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee’s plans [for the conduct of the battle], I determined not to interfere with his command of his brigade as long as it was commanded entirely to my satisfaction.” Both Stuart and Fitz Lee were supremely confident that they would soon have the Yankees on the run back across the Rappahannock.

As Lee surveyed the Federal line, his boss joined him. Lee told Stuart, “We are in a tight place” and then offered to turn the conduct of the pending fight over to Stuart. Stuart would have none of it, laughing, “No you don’t. I came as a volunteer and brought all the reinforcements I could find. Fitz, this is your fight. Command and I obey.” Lee replied: “I think there are only a few platoons in the woods yonder. Hadn’t we better take the bulge on them at once?” Stuart agreed that Lee should commence the attack.

While waiting for Averell to appear and believing he faced only a weak advance guard, Lee had deployed a dismounted squadron near the Wheatley Farm. It was from these men that Averell’s troopers received a volley of fire as the latter emerged from a stand of trees a mile from Kelly’s Ford. In response, Averell formed a line of dismounted men from the 4th New York on the north side of the road and a similar line of men made up of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry on the south side of the road. After two artillery pieces were placed in between the two Union regiments, he ordered the whole force to move to the edge of the wood and open fire.

It took a great deal of cursing and threats by officers to get the Federal line moving as ordered. As soon as the Yanks stepped out, Averell spotted possible trouble on his right flank. In his after action report on the battle, he recalled that to forestall the threat to the northern end of his line his men had to take possession of the Wheatley farmhouse and outbuildings before their opponents could do so. McIntosh sent a force of dismounted troopers from the 16th Pennsylvania and a section of artillery to secure the structures. Passing the buildings, McIntosh advanced beyond his right into the open fields to his front. With Colonel J. Irvin Gregg’s Keystone State men leading the way, the Federals attacked the Southern left. The 4th New York and 4th Pennsylvania soldiers advanced with a cheer against an enemy-defended stone wall on the Wheatley property, while 100 Federals from Gregg’s command crashed through the woods to hit the wall from the rear. The Confederates were soon driven from the wall, replaced by the victorious 4th New Yorkers and 4th Pennsylvanians.

Alarmed by the turn of events, Lee counterattacked with his entire brigade. After tearing down a rail fence to their front, the 3rd Virginia Regiment, hoping to flank the enemy, charged the stone wall in columns of four. Riding into a hail of blistering Union fire, the Virginians veered to their left, showing their flank to the enemy while they sought to find an opening in the wall. All the while they fired their pistols at the well-protected bluecoats. Finding no way to cross or breach the wall, the riders headed for the Wheatley farmhouse in hopes of flanking the Yankees out of their position there.

The Death of John Pelham

Sergeant Robert S. Hudgins of the 3rd Virginia remembered that during this charge “we gave them the old Rebel Yell, we hit them and went through their advance guard nearly up to the Stevensburg Road.” Colonel Thomas L. Rosser, leading the 5th Virginia Cavalry, soon joined the 3rd Virginia in the effort to turn the enemy right near the Wheatley house. If they succeeded, Averell’s line of retreat to Kelly’s Ford would be cut. However, the 100 men McIntosh had posted earlier to safeguard the Federal right poured such a devastating carbine fire into the approaching 3rd and 5th Virginia that the two units had to retreat. Following up on their opponents’ retirement, the Pennsylvanians went forward to a fence and poured hot fire into the Confederate flank. Still full of fight despite their recent reverse, the two Confederate regiments returned to attack the Union center but were quickly repulsed. A member of the 16th Pennsylvania described the latest Rebel charge as “a desperate one, [the enemy] riding up to the muzzles of our carbines, and attempting to force their way through the lane. All to no avail.”

During the first charge, Pelham impulsively joined in the attack. He had been helping position and fire Breathed’s artillery pieces before he dashed forward with the charging 3rd Virginia. Saber drawn, Pelham reached the stone wall, rose in his stirrups, turned his head toward the troopers following him and cried, “Forward! Let’s get them!” At that moment a Union artillery shell exploded on the wall, spraying lethal shrapnel. A chunk of metal the size of a cherry entered the back of the young artillerist’s skull, mortally wounding him. One of the South’s best artillery officers would soon be dead.

As the 3rd and 5th Virginia recoiled from the failed attack, Averell, uncertain of how large an enemy force might lie ahead of him, allowed the Virginians to escape. A determined push against the shaken units by McIntosh might have caused them to quit the battlefield and clinched a singular Union victory at Kelly’s Ford. But caution rode with Averell that day, and it meant that the two Rebel regiments still posed a danger to the Union force.

As McIntosh regrouped, Duffie formed the 1st Rhode Island, 4th Pennsylvania, and 6th Ohio in front of the left of the Federal line and ordered a mounted charge. He did this without first seeking permission to do so from his division commander. He kept the 4th New York in reserve. As Duffie’s men took off, Averell, taken aback by Duffie’s unauthorized, bold initiative, instructed Reno to advance three of his squadrons to support Duffie’s attack, while the balance of the reserve brigade waited for orders to pitch into the fray.

As Duffie’s men rolled forward, led by the colonel, two squadrons of the 5th U.S. Cavalry joined the charge. Almost at the same instant, McIntosh’s left flank units attacked. Lee led the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Virginia to meet Duffie’s assault. Seeing Lee’s men coming out of the woods, Duffie halted his movement. When the Confederate troopers came within 100 yards of the Federal line, the 1st Rhode Island plunged ahead to meet the Rebels in the open field. The 6th Ohio and two squadrons of the 4th Pennsylvania followed on the right, while two squadrons of the 5th U.S. trailed on the Union left, supporting the Rhode Islanders.

The command “Charge!” rang out on both sides, and as one 6th Ohio trooper recounted, “It was like the coming together of two mighty trains at full speed.” What followed was a clash of cold steel, firing of pistols, and the shouts of hundreds of combatants intermingled with explosions of artillery shells. Saber cuts and gunshots drew blood and toppled men and horses to the ground. As the melee continued, the 3rd Pennsylvania took up positions to the west of the Wheatley farm buildings on the Union right flank where the 3rd and 5th Virginia had once stood. Fearing the move would result in his left being turned, Lee ordered his outnumbered force to disengage from Duffie and retreat to the right. The discomforted Rebels were hotly pursued by the 1st Rhode Island, which swept up some Confederate prisoners. But the boys from the Ocean State rode too far ahead and were struck in turn by a fresh Southern squadron, losing two officers and 18 enlisted men in the running fight.

Leaving the field, Lee withdrew a mile to the west to rally his men and forge a new battle line. He formed a new defensive position along Carter’s Run, placing mounted skirmishers in his front and bringing up Breathed’s guns and placing them behind his main line. Lee’s new site was a strong one, 600 yards of flat ground bordered on both sides by woods. The road to Kelly’s Ford ran through the center of the Confederate line and was lined on both sides by a fence. At right angles to the road a plank fence intersected the center of the plateau.

![Harper’s Weekly published this dramatic drawing of the cavalry fight at Kelly’s Ford, referring to the battle as the war’s “first stand-up cavalry [battle] on a large scale.” The scrap gave the embattled Union troopers a much needed jolt of energy and confidence.](https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/CW-KellysFord-1-e1664793824191.jpg)

For a half hour Averell regrouped his men and then went forward toward the new Confederate position. Discovering that the ground to the left of the road was too marshy for mounted action, he placed his left on the highway and spread his right to the edge of the woods. Due to a shortage of ammunition, two of his artillery pieces were sent back to Kelly’s Ford, leaving him with only four cannons. The Federal force finally advanced and found their Southern antagonists glaring at them over 600 yards of clear, level ground sloping gently down to the banks of Carter’s Run.

Lee’s Counterattack

Although the Federals had a large numerical advantage, Averell did not intend to attack Lee’s new position. Undaunted by the odds against him or the drubbing he had already received from his opponents earlier in the day, Lee elected to once more take the fight to the enemy. The Confederate commander’s decision was probably reinforced by the fact that if his attack failed Averell’s frequently displayed caution would no doubt prevent him from exploiting any Confederate failure with a strong Union counterattack.

Lee sent the 1st, 3rd, and 5th Virginia Cavalry at the center of the Union line, while the 2nd and 4th Virginia struck Averell’s left. After crossing Carter’s Run, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th Virginia bore down on three squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania posted on either side of a small stand of trees. Seeing the threat, Averell brought up the 1st U.S. Cavalry and placed it 100 yards to the left of the Pennsylvanians. The Union troopers deployed in a double line, the first line with carbines at the ready, the second rank eager to use their sabers.

As the Confederates slogged through the muddy ground, their left was exposed to small-arms fire delivered by the 16th Pennsylvania. The Confederate advance was slowed by the muddy terrain, and their close-ordered formations quickly became ragged and fragmented. Colonel William R. Carter’s 3rd Virginia was hit by enemy artillery fire the minute it started its advance toward the Yankee position. After they had passed through the enemy’s lines, the Federal gunners abandoned their battery. The 3rd Virginia then attempted to capture the enemy guns but was prevented from doing so by a double fence and determined Union sharpshooters. Under heavy fire, the unsupported 3rd Virginia retreated to Carter’s Run.

As the 3rd Virginia retired under enemy fire, its sister regiments, the 1st and 5th Virginia, came within 25 yards of the position held by the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. As the Rebel horsemen approached in three assault columns, the troopers from the Keystone State poured lethal volleys into them. The Southerners retreated in small groups but then turned to charge again. The time was favorable for a Federal counterstroke before the retreating Virginia units could rally and charge once more. After an unaccountable delay, the 3rd Pennsylvania was ordered to charge, and the Confederates were pushed back to where their artillery battery was posted.

While events took place on the Federal right, the 2nd and 4th Virginia tried to turn the enemy’s left flank. Under intense artillery fire and having to knock down a fence that stood in the way, the gray-clad troopers approached the Federal line only to veer to the left and right due to the heavy cannon fire they were receiving. On the Union left, the 1st Rhode Island, parts of the 1st and 5th U.S., and the 6th Ohio crashed into the Virginians. The toll of dead and wounded was great, and the Confederates, outnumbered, broke and ran for Carter’s Run. Reno joined the pursuit of the enemy but halted at the creek where Lee’s attack had begun and was soon joined by the rest of the Federal division.

Concerned about the reported presence of Rebel infantry, low ammunition, and used-up horses, Averell ordered a retreat to Kelly’s Ford. Reno’s regulars covered the retrograde movement, which was shadowed by small bodies of Confederates with an occasional artillery shell fired at the withdrawing bluecoats. The weary Federals reached Morrisville at 11 am. By March 18 the division was back at its camp at Hartwood Church.

As they departed Kelly’s Ford, Averell’s troops were in high spirts. They had won in a convincing fashion in what the New York Times termed “the First Real Cavalry Fight of the War.” No longer would the Union cavalry feel inferior, overmatched, and on the defensive when confronting their Confederate counterpart. One Federal officer who took part in the fight wrote, “We are more than ever sure that on a fair field the Rebel Cavalry can’t stand [up to] us.” In this sense, the Saint Patrick Day’s victory, incomplete as it was, exerted a more powerful and longer lasting impact on the Eastern cavalry than many later clear-cut victories. Sometimes perceptions matter more than reality.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments