By Steve Lilley

Brigadier General James S. Rains’s Confederate cavalry rode confidently toward the prosperous little town of Lexington, Missouri. Dressed in Missouri homespun, Rains’s men hardly looked the part of a flying military column, but most of the hard-riding horsemen had known only victory during their short service. As they approached Lexington’s outskirts, blue-coated Federal pickets opened fire, driving the horsemen back. Even the recently commissioned Rains could see the insanity of leading a headlong cavalry charge into the town. Although Rains habitually overestimated his opponents, Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, his commanding officer, surveyed the situation more carefully and chose to wait for his infantry and artillery to arrive before further testing the Federals’ resolve. It was September 12, 1861.

Price knew Lexington well. It lay 65 miles southwest of his tobacco plantation at Keytesville, and he had traveled there often for business and pleasure. On this warm, late summer day, Price was visiting Lexington for very different reasons. He intended to dispose of a small Union army dug into its green hillsides, a situation he would not have dreamed possible a year earlier. An ardent unionist, “Old Pap,” as many Missourians called Price, had served as Missouri’s governor and later as one of the state’s congressmen. Even after Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, he fervently hoped that Missouri would remain neutral.

That would prove difficult. After Sumter’s fall, President Abraham Lincoln had requested that the state send four regiments as part of his call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion, but Governor Claiborne F. Jackson refused. Knowing that a majority of his fellow Missourians probably favored neutrality, Jackson remained coy about the state’s relationship with the emerging Confederacy. In the meantime, he asked the legislature to raise a state militia and quietly sought arms from the new Southern government.

Nathaniel Lyon harbored no doubts about Missouri’s ultimate loyalty. Rightly suspecting that the state was raising troops to aid the rebellion, Lyon acted decisively. On May 10, the zealous young Federal brigadier general seized Camp Jackson in St. Louis and arrested 800 state militiamen. Lyon’s action triggered a riot that resulted in Union troops, many of them German immigrants, gunning down 15 civilians while losing two of their own men.

The incident outraged many Missourians, including Price. One of his friends, Horatio Jones, later observed that Price was “the picture of wrath. I have always had the feeling that the Camp Jackson affair toppled him over.” It also prompted the state’s general assembly to form its own militia, the Missouri State Guards, and to commission Price a major general to command it.

In June, Federal forces under Lyon’s command drove the legislature and Governor Jackson from the capital in Jefferson City and chased them westward across the state. Not only did Lyon’s bold campaign preempt a suspected Missouri rebellion, it also enabled the St. Louis politicians to wrest control of the state from rural Democrats. On July 31, a state convention met in St. Louis under the protection of Federal troops, declared Missouri government offices vacant, and, in an act that was probably unconstitutional, established a provisional government under the newly appointed Republican Governor Hamilton Gamble.

In response, on August 5 Jackson proclaimed Missouri a free and sovereign state. Five days later, Missouri’s legally elected but temporarily dislocated government struck a blow for state sovereignty. On August 10, a combined army composed of Confederate regulars under Brig. Gen. Benjamin McCulloch and Price’s Missouri State Guards soundly whipped the Federals and killed the feisty Lyon near Springfield, Missouri, at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.

Even as the opposing forces fought, political confusion and uncertainty reigned in Missouri. Although it was a slave state, Missouri had not joined the Confederate States of America. Like Price, most Missourians would only take up arms against the Union if the Federals invaded the state and placed it under the control of U.S. Army troops. Many of those troops were Irish and German immigrants and hated by the natives. Now that invasion had taken place.

After thrashing Lyon at Wilson’s Creek, Price saw an opportunity to rescue Missouri from the Federal invaders and their foreign-born minions. McCulloch would have none of it. Despite their shared victory, McCulloch considered Price an overbearing amateur commanding a half-armed mob. When Price invited the Confederate general to join him in freeing Missouri from Federal control, the Texan declined and marched his army back into Arkansas. Price would have to fight alone.

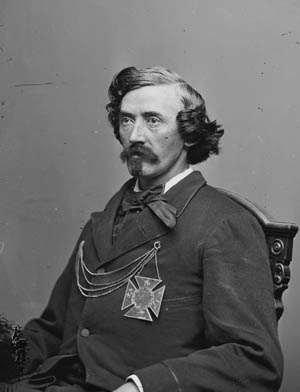

While the Missouri State Guards’ commander had no West Point training, he had successfully commanded troops during the Mexican War. Many professional officers scoffed at the part-time general, but Price displayed two attributes his critics often lacked: He handled volunteer troops well, and he acted decisively. Under his leadership, thousands of volunteers formed infantry and cavalry units. The fledgling army even assembled a small body of artillery and learned how to manufacture munitions for their cannons. One of these, a 12-pounder field piece nicknamed “Old Sacramento,” Price had brought back from the Mexican War. Having scattered one Federal army, he prepared to drive the rest of the invaders from the state.

On August 20, Price issued a proclamation datelined Jefferson City but more likely issued from Springfield that declared his army legally and constitutionally authorized to resist Federal usurpation of power in Missouri. He also proclaimed his determination to protect all Missourians regardless of their sympathies unless they supported Gamble’s provisional government. These he would consider enemies. On August 25, Price and his volunteers began their northward march of liberation.

Major General John C. Frémont, Lincoln’s recently appointed western district commander, viewed the situation with horror. Headquartered in St. Louis, the legendary Pathfinder scrambled to assemble a military force to hold Missouri for the Union and protect Hamilton Gamble’s rump government. Threatened by Confederate forces arrayed in unknown strength along Missouri’s southern borders and facing revolt within St. Louis, Frémont attempted to discourage the rebellion with both words and military action. On August 30, Frémont proclaimed martial law throughout Missouri, announced that the U.S. government would free any slaves owned by disloyal masters, and warned that any citizens bearing arms without proper authorization would be shot. Predictably, that proclamation appalled Lincoln and drove more recruits into Price’s army.

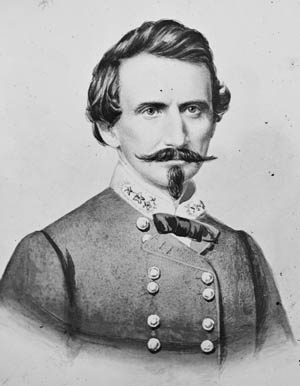

On that same night, Frémont’s subordinate, Colonel Jefferson C. Davis, ordered Colonel James A. Mulligan to march his brigade, the 23rd Illinois Volunteers (known as the Irish Brigade), from Jefferson City to Lexington and hold it at all costs. Mulligan’s orders included instructions to relieve Colonel Thomas A. Marshall’s cavalry regiment, which Confederate troops had hemmed in at Tipton. Mulligan eagerly complied. The son of Irish Catholic immigrants, he had become a Chicago lawyer and saw prospects for political advancement through military achievement. Mulligan issued 40 rounds of ammunition and three days’ rations to his men, said goodbye to his pretty, 19-year-old wife, and enthusiastically led his command westward.

Price faced minimal opposition on his own march. On September 2, his army brushed aside 500 of James Lane’s Jayhawkers, commanded by Colonel James A. Montgomery, in a skirmish at Drywood Creek near the Missouri-Kansas border Fought in prairie grass more than seven feet high, neither side inflicted much damage on the other, but captured soldiers revealed Price’s destination. The Federals now knew that the Missourians were headed for Lexington.

Estimating Price’s column to number at least 10,000 men, Lane, who commanded only 2,000 troops, avoided further battle but sent a request for reinforcements to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Leavenworth’s commander, Major W.E. Prince, forwarded Lane’s request via telegraph to Frémont. Thoroughly distracted by the controversy his August 30 proclamation had ignited, Fremont responded tentatively to Lane’s request.

There was nothing tentative about Price’s actions. He drove his men as much as 22 miles daily. Some of the State Guards marched for 24 hours without eating. Heavy rain doused the Missourians’ campfires but failed to dampen their spirits. Farmers and townspeople greeted the troops as liberators and supplied them with food and drink. All along Price’s line of march, young men saddled their horses, grabbed their fowling pieces, and fell in line with Old Pap’s legions.

As Price’s host approached, Union Colonel Everett Peabody evacuated Warrensburg, led his largely German regiment toward Lexington, and sent word to Mulligan of his intentions. The Guardsmen entered Warrensburg at dawn, just as more rain turned the roads to slime. Price, discovering that the Federals had escaped, halted his hungry, exhausted column and observed with satisfaction that the town’s citizens “vied with each other in feeding my almost famished soldiers.”

By the time Mulligan received Peabody’s news, he had reached Tipton, only to learn that Marshall had also made good his escape and fled to Lexington. Mulligan marched his command in the same direction and notified Frémont that he would need reinforcements immediately. The Irish Brigade reached Lexington on September 12. Mulligan ordered the men to halt, detail their uniforms, wash their faces, and slick down their hair so that they could make a proper impression on the town’s residents, especially the young ladies.

The town the Federals entered was the jewel of western Missouri. Its bank held larger deposits than any other bank in the state. Made prosperous by surrounding hemp plantations and rope walks, Lexington had once served as the home of Russell, Waddell and Majors, the wealthy shipping company that originated the Pony Express. Thousands of wagons and teams had crowded its streets and Missouri River dockyards. During the 1850s, the town’s residents achieved infamy by routinely searching steamers and confiscating the firearms of Free Staters bound for Kansas. Now Lexington lay under the heel of Federal troops.

A brief conference among the Union colonels determined that Mulligan enjoyed seniority and would exercise command over their combined force of 3,500 troops. Mulligan ordered the town’s stately Masonic College occupied and buried for safe keeping confiscated property, including the state’s Great Seal and $900,000 liberated from Lexington’s bank. He then began preparing for a siege. His troopers felled ancient oak trees on the campus to clear a field of fire. In short order, Mulligan’s men dug earthworks with abatis and rifle pits encompassing 17 acres around the college. The defenders augmented their works with explosive devices activated by trip wires and threw up ramparts 12 feet tall and 12 feet thick. Price’s enthusiastic amateurs might have enjoyed superior numbers, but Mulligan felt confident that his command could hold off the rebels until reinforcements arrived—if they arrived.

Rains’s cavalry, with Price in the vanguard, arrived first. Rather than throw his tired men at prepared positions, Price camped his troops at the fairgrounds two miles away to await dawn and reinforcements before attacking. Knowing the State Guard had arrived, the Federals continued entrenching well after dark. “It was a night of fearful anxiety,” Mulligan remembered. “None knew at what moment the enemy would be upon our devoted little band.” As his men threw up breastworks, Mulligan sent word to Jefferson C. Davis that Price and Jackson threatened him with a force of between 10,000 and 15,000 men. “We will hold out,” he assured Davis, but added: “Strengthen us. We will require it.” Davis forwarded Mulligan’s appeal to Frémont.

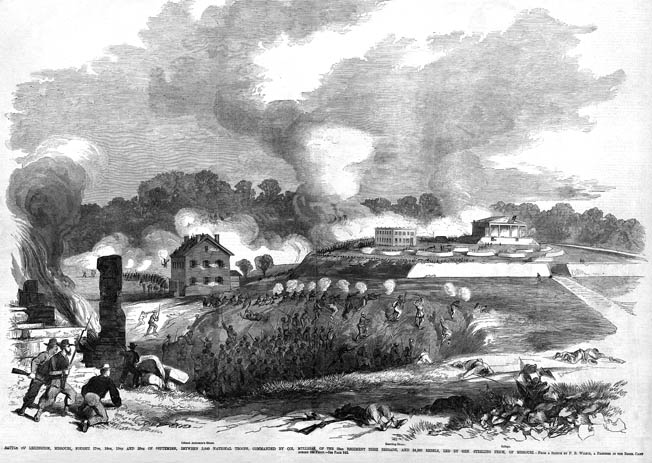

At daybreak on Friday the 13th, a messenger burst into Mulligan’s headquarters with news that the State Guard was crossing the covered bridge into town. Mulligan dispatched three companies that repelled Price’s advance and burned the bridge. A similar attempt by Price’s men to enter Lexington along the Independence Road also bogged down when six companies of the 13th Missouri and some Illinois cavalry blocked their path. Fighting raged in the town’s cemetery, where combatants sought cover behind the tombstones.

That afternoon, Captain Henry Guibor, a veteran of the Camp Jackson affair and Wilson’s Creek, arrived and unlimbered his artillery battery. A well-placed volley of homemade grapeshot and canister scattered Federal officers, who retreated inside their works. The bluecoats sheepishly explained that the cannon fire had panicked their horses. When Mulligan ordered his own field pieces to reply, a fortuitous round blasted a Confederate caisson, sending clouds of white smoke shooting skyward and prompting loud Federal cheers.

For the moment, Price felt satisfied at having driven the Union forces into their trenches.“The enemy fled like rats,” sneered the tough Ozark native, Brig. Gen. J.H. McBride. With darkness approaching and his ammunition running short, Price again withdrew his troops to the fairgrounds, feeling that time was on his side. He had pushed his cavalry and advanced infantry units to the limit in pursuit of the Union troops. Now that his adversaries had dug in, he waited for his supply train and lagging regiments to reach the battlefield.

Lexington Besieged

After the fighting died down, State Guard commander Monroe M. Parsons negotiated a truce with the Federals, during which time both sides retrieved their wounded from the day’s fighting. The siege began in earnest. Pickets occasionally exchanged fire, and Price’s artillery bombarded Union positions. The townspeople recognized “Old Sacramento’s” rumbling boom. For years after the Mexican War, the cannon had been fired to commemorate Lexington’s 4th of July celebrations.

During the lull, the Federals improvised a foundry in the college’s basement where they fashioned 150 rounds of grapeshot and canister for their 6-pounders, but the defenders quickly faced supply shortages. Having begun their march with enough food for only a few days, Mulligan put his men on half rations. The Federals still found it necessary to commandeer food from the locals. Even worse, Marshall’s cavalry carried only pistols and sabers, making them ineffective for siege defense. Some scrounged weapons from Lexington’s residents, a tactic that only deepened resentment toward the occupiers. Water quickly became scarce.

As Price’s units reached Lexington, he deployed them in a ring around the Federal positions, denying the enemy access to the river and posting guards at nearby springs. The town’s cisterns could not supply an additional 3,500 men, much less their animals. The Union cavalry’s fine horses proved more of a liability than an asset, drinking much and contributing little. Heavy rains briefly relieved the water shortage but also turned the trenches into boot-sucking slops. Day after day the mud-spattered Federals watched as enemy units poured in and tightened Price’s grip on the town. On September 15, Father Thaddeus Butler, the Federal chaplain, held mass on the college’s hillside. “All were considerably strengthened and encouraged by his words,” said Mulligan, “and after services were over we went back to work, actively casting shot and stealing provisions from the inhabitants round about.”

Frémont took his time marching to Lexington.

As Father Butler celebrated the mass, Price’s troops continued to take up positions surrounding the Federal works. Brig. Gen. Thomas A. Harris brought his 2,000-man division from northeast Missouri, where one of his recruits, 25-year-old Hannibal resident Samuel Clemens, had recently decided that the soldier’s life was not for him and “lit out for the territory” of Nevada with his older brother Orion. Clemens was not greatly missed. By September 17, Price’s supply wagons reached Lexington. With his army in place and fully provisioned, Price ordered an attack for the next morning.

If Mulligan had ever seriously considered evacuating Lexington, the opportunity had long since passed. Harris’s and McBride’s divisions stood between the Federals and the Missouri River. McBride’s ragged, barefoot, undisciplined Ozark boys resembled an armed mob but were crack shots and fearless in battle. To the northeast, Rains’s division held the high ground. Clark’s division joined Rains’s left, and Parsons’ division extended from Clark’s left along Main Street to the courthouse. Green’s and Steen’s divisions held the ground along Pine and Tenth Streets down to the river bluffs.

For amateur militia, the State Guard opened the battle with considerable flair. Units advanced, banners snapping in the breeze, led by a full military band. Even Mulligan found it impressive. “They came as one dark moving mass,” he reported, “their guns beaming in the sun, their banners waving, and their drums beating—everywhere, as far as we could see, were men, men, men, approaching grandly.”

Price’s 16 cannons opened fire on the Federal positions. Most of the Union soldiers had little combat experience, but Father Butler walked among them blessing the men as he passed, calming and reassuring them. Well dug in, the Federals held their ground. Inspired by the cannonade’s grandeur, Rains offered a gold medal to the artillerymen who could shoot down the Stars and Stripes from the Union battlements. When the flag fell, he proclaimed, the infantry assault would begin. Despite the gunners’ best efforts, hours passed with the flag unscathed.

The Federals’ seven field pieces replied to Price’s barrage, and Mulligan’s entrenched soldiers blazed away at the advancing State Guardsmen, most firing high.

Whizzing shot prompted most of the Rebel officers to dismount as they advanced, but Price remained in the saddle scanning the enemy emplacements. A stray piece of grapeshot smashed the field glass in his hands but somehow left him unharmed. Ignoring the close call, Price retained his composure and, to his men’s astonishment, remained in the saddle directing the battle for another 20 minutes before leaving the front line.

Fight For Anderson House

The home of Oliver Anderson drew more than its share of artillery fire. Lying outside Mulligan’s works, the elegant, two-story Greek Revival brick home had been converted into a Union field hospital. Clearly marked with a hospital flag, the Anderson House could not properly be considered a legitimate target, but the attackers complained that Union soldiers were using its roof as a snipers’ roost. Determined to neutralize the threat, State Guard artillery batteries raked the house with hot shot and shell.

Cannonballs crashed through the building. One burst through the attic and fell to the floor in a second-story hallway, leaving a hole in the ceiling. A Union officer, Major R.T. Van Horn, entered the Anderson House and found a ball smoldering on the floorboards. Grabbing a shovel, he scooped up the ball and threw it out a window. A 13-year-old boy named Linthicum volunteered to take over the job. Before Van Horn could voice his doubts about the boy’s ability to handle the task, a ball burst through the wall and rolled to a stop. Linthicum instantly seized the shovel and disposed of the smoking projectile. Convinced that the boy was more than equal to the job, the officer left.

Once his cannons failed to neutralize the threat from the Anderson House, Price ordered Harris and Colonel B.A. Rives to assault the building. The Guardsmen emerged from the shelter of the river bluffs and advanced through tall weeds toward their objective. Occasionally, Confederate soldiers detonated Federal booby traps, but the troops behind them passed safely through the smoking craters. Within minutes, the Guardsmen entered the house from which the snipers had fled. A search of the building revealed some escaped slaves hiding in the basement. Rives ordered them returned to their masters. Confederate troops now held an ideal position from which to fire into the Federal trenches.

Enraged that Price’s men had violated the sanctity of a hospital building, Mulligan ordered companies from the Home Guard and the 14th Missouri to retake the Anderson House. The troops looked nervously at the open field in front of their objective. Having already witnessed the toll that massed gunfire inflicted on men making grand charges, they refused to budge. Appalled by their disobedience, Mulligan unleashed a torrent of obscenities and called for volunteers. The Irish Brigade’s Montgomery Guards and some of Peabody’s Germans took up the challenge, fixed bayonets, and swept the attackers from the hospital. As the Federals burst into the building, three State Guard troops attempted to surrender, but the Federal soldiers bayoneted them on the spot. One resourceful Rebel, seeing that he could neither escape nor surrender, slipped into bed next to a wounded Illinois soldier and waited for matters to calm down. The Federal victory proved short lived. Confederate troops retook the Anderson House that evening and held it for the remainder of the battle.

Federal troops continued to suffer from lack of water. Price’s troops continued to guard the two springs beneath the bluffs and blocked Union access to the Missouri River. The cisterns within Mulligan’s works had run dry supplying the cavalry’s horses, many of which had fallen to gunfire. Federal canteens ran dry. During their occupation of the Anderson House, Union soldiers maddened by thirst had scuffled over drinks from bloody wash pans in the hospital. The late summer sun beat down on the men in the trenches whose lips cracked and bled from tearing open paper cartridges with their teeth. Hoping to augment the water supply, Mulligan detailed men to dig groundwater wells.

Late in the day, the Federals attempted a counterattack on Rains’s front, but his weary Guardsmen drove them back. Both sides settled in for the night. Price’s men remained in position, sleeping on their weapons without blankets or rations. A few of the more fortunate soldiers feasted on sugar that Rives’s troops had commandeered when they captured two steamers loaded with supplies on the riverfront. The vessels’ capture completed Mulligan’s isolation from the outside world.

After darkness fell, troops delivered Frank B. Wilkie to Price. Thoroughly hung over, the captive identified himself as a war correspondent for the New York Times and claimed that he wanted to write an account of the Lexington battle sympathetic to Missouri. As proof of his good will, Wilkie invited the Missouri general to review his article covering the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. Price read the story and, concluding Wilkie could do little harm, wrote the tottering correspondent a safe-conduct pass, adding the cautionary words: “Keep an eye on him. He is a Yankee.”

September 19 dawned warm and soon grew hotter. Each side continued their cannonade, while some Rebels banged away harmlessly with their short-ranged shot guns. At the beginning of the battle, Price had evacuated the town’s civilians for their own safety. A number of locals fell in alongside the State Guardsmen, augmenting Price’s numbers. One resident, a Lexington farmer in his sixties, arrived carrying his flintlock and a lunch pail. Each morning he fired at any Yankee who dared show himself above the earthworks, took a brief lunch break, smoked his pipe, and then returned to the firing line.

Despite Price’s growing strength and his own dwindling supplies, Mulligan assured his embattled troops that relief columns would soon arrive. Unknown to him, Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis’s six Union companies had marched from Mexico, Missouri, to within 15 miles of Lexington. Unfortunately for the Federals, Price, learning of Sturgis’s approach, sent Parson’s division to ambush the column. As Sturgis advanced through the fields of ripening corn, a black man intercepted the general and alerted him to the danger. A West Pointer who had graduated with classmate Thomas Jackson, Sturgis possessed none of Stonewall’s daring. Rather than confront a superior force, Sturgis hurriedly turned his column toward Kansas City, discarding 200 tents and similarly abandoning Mulligan to his fate. By noon Parsons’ men had returned to their positions at Lexington.

Advancing With Hemp Bales

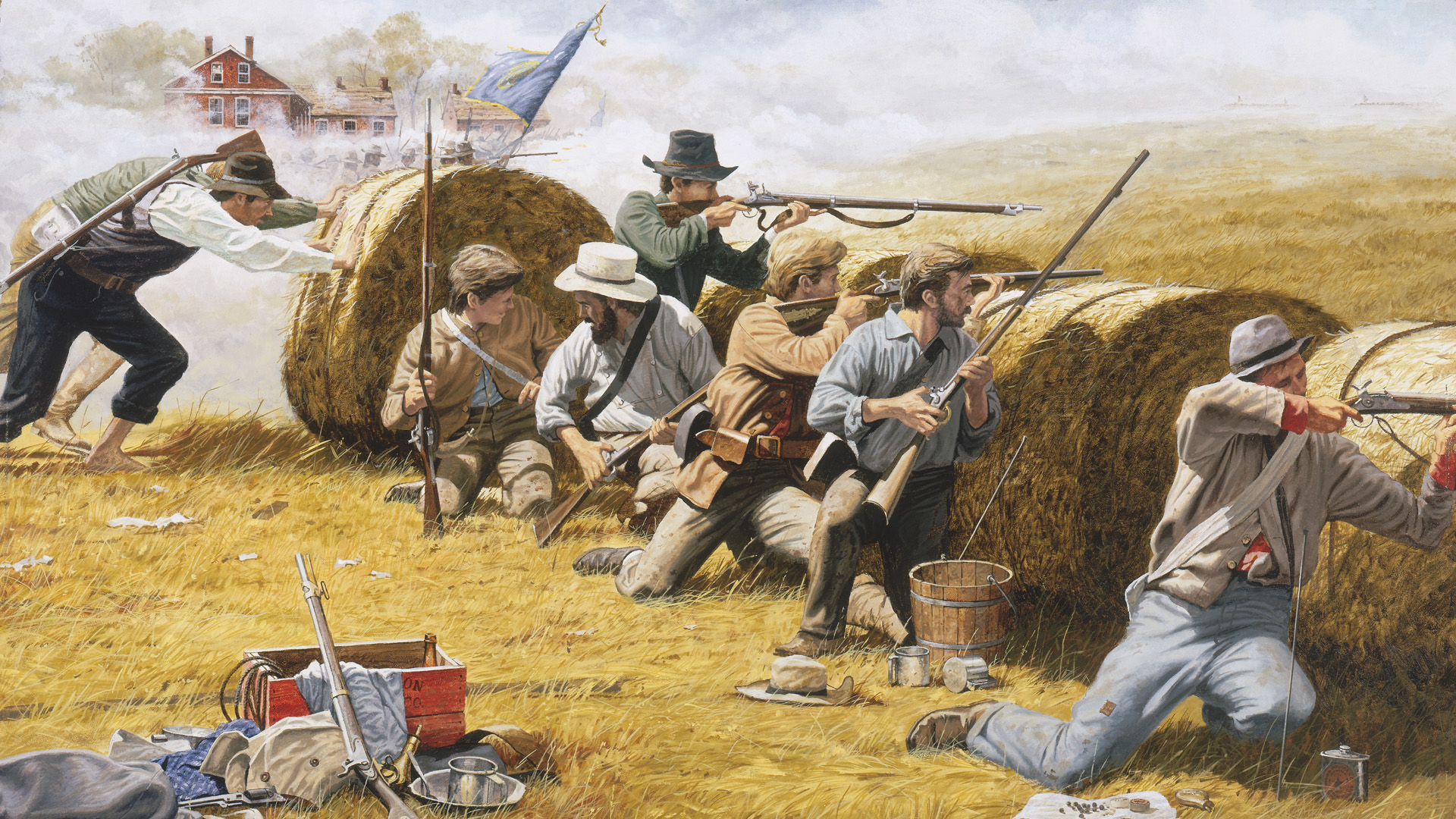

As Federal hopes of victory faded, Confederate impatience with the slow pace of the siege grew. Some of Price’s officers urged him to take advantage of his larger force and assault Mulligan’s lines. Price demurred, assuring his officers that “it is unnecessary to kill off the boys here. Patience will give us what we want.” On the afternoon of the 19th, some of Price’s troops began advancing on Federal positions behind a rolling breastwork of hemp bales that they had found at the dockyards. The Guardsmen found that once the bales had been soaked with water, they repelled both artillery shells and bullets. The bales’ first use appeared promising. During the night, the men of Harris’s 2nd Division rolled more than 130 bales into place.

When the sun rose on the morning of the 20th, the Federals saw a long line of hemp bales arranged to the north and west of their entrenchments. In some places the bales lay within 100 yards of the Union works. Confederates rolled them forward in a continuous line while their riflemen fired on the Federals from behind the improvised bulwark. Enterprising Union artillerymen directed cannon fire against the bales, only to see them rock backward after absorbing the shock. Amused by the Federals’ frustration, Harris quipped that the hemp bales “elicited the obstinate resentment of the enemy, who was profuse in the bestowal of round and grape shot, and was not at all economical of his Minie balls.” Rebel spirits soared as the line advanced. “My own men were so fired up with enthusiastic courage,” Colonel J.T. Hughes later reported, “that it was almost impossible to prevent them from leaping over the bales of hemp and scaling the enemy’s entrenchments, and plunging right into the ditches.” Within a few hours Price’s mobile rampart had positioned the Missourians for a short, final dash into the Federal defenses.

At about 2 pm, a white flag appeared above the Union earthworks. One of the Union officers raised the flag despite Mulligan’s warnings that any unauthorized attempt to surrender would result in the offender’s execution. Firing ceased on both sides, and Price sent a courier under a flag of truce to ask Mulligan why the shooting had stopped. In his reply, Mulligan brazenly wrote, “General, I hardly know unless you have surrendered.” Despite his pluck, Mulligan knew that the end had come. Most of his troops had exhausted their ammunition, food, and water, with no word of relief reaching the besieged Federals. Additional white handkerchiefs began fluttering from Union bayonets. Mulligan polled his officers; they voted to surrender.

The State Guard’s adjutant general, Colonel Thomas Snead, conveyed Price’s terms to Mulligan through Colonel Marshall. A transplanted Virginian, Snead was a college professor of ancient languages and an attorney with no military experience prior to his commission. Price, he informed Marshall, required the Federals’ unconditional surrender. The Union colonel responded that he would pass along Price’s terms to Mulligan. Snead feared that additional Federal troops could arrive at any time. If Mulligan did not accept the terms within 10 minutes, he warned Marshall, the Missourians would assault the Federal positions. Marshall disappeared into the Union works and returned to Snead just as the second hand on the colonel’s watch swept inexorably toward the deadline. Mulligan had accepted Price’s terms.

Price proved a magnanimous victor. In the spirit of Southern chivalry, he allowed all Federal officers to keep their side arms, horses, and personal property. Mulligan’s command stacked their muskets and marched out of their trenches to be paroled. Price could not accommodate so many prisoners and happily sent them on their way. Soldiers returned civilians who had joined the Federals to the “custody” of their wives. As the bluecoats marched into the open, the Irish regimental band marched around the college grounds playing defiantly. Patient as ever, Price allowed them to continue until their anger cooled. That night, he treated the Federal officers to a champagne dinner.

Mulligan, who had suffered a wound, and his young bride, who had joined him at Lexington, remained as prisoners. Price treated his captives as honored guests, transporting them in his personal carriage and lodging them in a comfortable tent near his own. Price later sent the Mulligans to St. Louis with an armed escort under a flag of truce. From there, the dashing Irish colonel returned to Chicago, where he received a hero’s welcome.

The End of Missouri’s Bid For Secession

From Washington, General Winfield Scott telegraphed Frémont that President Lincoln expected him “to repair the disaster at Lexington without loss of time.” Despite Lincoln’s impatience, Price’s army lingered in Lexington for another two weeks before Frémont finally began a leisurely march westward with 38,000 troops. Price’s troops found the time for band concerts and dances with village girls all along their line of withdrawal.

Price’s victory at Lexington, though small by comparison to the bloody battles that still lay months in the future, accomplished much. At the cost of only 97 casualties, 25 dead and 72 wounded, he had captured more than 3,300 enemy troops and inflicted 150 casualties. His poorly armed troops obtained more than 3,000 rifles, seven cannons, 750 horses, and large quantities of wagons and equipment. Although Price returned all the cash seized by the Federals from the Farmer’s Bank of Lexington, he retained $37,000 in badly needed gold which the state legislature had authorized him to appropriate for military expenses. Most importantly, he had lifted the morale of secessionists and State’s Righters throughout Missouri.

Had the Confederacy achieved a string of victories as inexpensive and profitable as Lexington, it might have won its independence. On the day that Mulligan surrendered, the Confederate Congress authorized President Jefferson Davis to form an alliance with Missouri. The action proved more symbolic than real. No Confederate army marched to join Price in halting Frémont’s cautious advance. Such decisive action might have rallied thousands of wavering Missourians to the Southern cause.

Instead, Price’s troops went into winter quarters. Gradually, more than half of the Guardsman drifted away, returning to their warm homes and well-stocked cellars while the Union forces in Missouri grew. By the following spring, the opportunity to secure Missouri’s independence and its effective membership in the Confederacy had passed. Eighty-six years earlier, Massachusetts farmers had defied the British Empire at another Lexington and thousands of armed Americans from 12 other colonies had joined them in a war for independence. The outcome following the Battle of Lexington, Missouri, had proved far different.

I lived just down the road from Lexington, MO, in Higginsville, MO.

There is a canon ball still imbedded in the upper part of the far left (as you look from the street) column of the court house.

Back in the 1960s, there were a few houses left in Lafayette County and the Lexington area that were around during the Civil War.