By Donald McConnell & Gustav Person

When the Civil War erupted in April 1861, the 10 companies of the 4th U.S. Infantry were spread along the West Coast from Puget Sound to the Gulf of California in various small, far-flung garrisons. After distinguished service in the Mexican War and garrison duty along the Great Lakes from Mackinac to Plattsburgh, the regiment had spent the last nine years garrisoning posts, guarding the coast, escorting new settlers, and fighting Indians. Company H, commanded for a time by Captain Ulysses S. Grant in the early 1850s, was based at Fort Vancouver in the Washington Territory.

The Regular Army in the Civil War

With the outbreak of the Civil War, authorities quickly realized that the main body of the Regular Army would be needed back East to form a reserve force and train the multitude of state volunteer forces that were hurriedly mustering in to suppress the rebellion. The 4th returned by sea after a disease-ridden march across the Isthmus of Panama. It arrived at New York and then traveled by train to the camps of the Army of the Potomac around Washington, D.C., in November 1861.

In the spring of 1862, the available Regular infantry regiments in the capital were formed into two brigades in the 2nd Division of the V Army Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Sykes, who had commanded the Regular battalion at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. They accompanied the Army of the Potomac to the James Peninsula in March 1862, and later fought in the Seven Days Battles in June and July. Returning to northern Virginia that summer, the Regulars fought at Second Bull Run and Antietam. They were heavily engaged at Fredericksburg in December, and then went into winter quarters around Falmouth, Virginia. After service at Chancellorsville in April and May 1863, they returned to their winter camps while their main opponent, General Robert E. Lee, made plans for his second invasion of the North.

During the disorderly retreat after the Battle of Chancellorsville, most of the Regulars lost their heavy Model 1853 knapsacks, which weighed up to 50 pounds. The knapsacks carried the soldiers’ greatcoats, spare clothing, wool blankets and personal items. Because the knapsacks were not replaced before the Gettysburg campaign, most soldiers adapted by rolling their remaining personal items in a vulcanized, gum rubber blanket (the forerunner of the modern poncho), tied in a horseshoe roll, and worn over the right shoulder. This greatly reduced their burdens. The soldiers carried blackened canvas haversacks on their left hips for their field rations and canteens containing about three pints of water. The basic load of 40 rounds for the .58-cailiber Model 1861 Springfield Rifle-Musket was carried in a cartridge box worn on the right hip. Waist belts supported the small pouches for percussion caps worn to the right of their brass U.S. belt buckle and the triangular socket bayonet in its scabbard worn on the left hip.

Per general orders of the Army of the Potomac in March 1863, each Regular wore a white Maltese Cross cloth badge on the crown of his Model 1858 Forage Cap. This was the insignia of the 2nd Division, V Army Corps, and it was the origin of the organizational patches each modern soldier wears on the sleeves of his combat uniform. The Regulars wore sky-blue trousers and dark-blue, four-button Model 1858 Fatigue Jackets.

The 4th U.S. Infantry Regiment

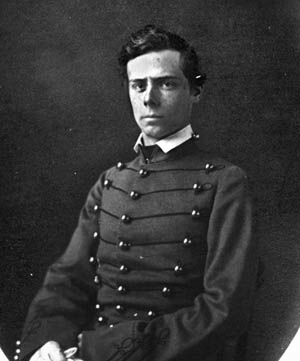

By the late spring of 1863, the 4th Infantry, through casualties and attrition, had been consolidated into four companies (C, F, H, and K), commanded by Captain Julius W. Adams, Jr., who rose to command of the battalion-sized regiment. Adams, the son of a former commander of the 67th New York Volunteer Infantry, graduated from the United States Military Academy in the class of 1861. He remained at the academy after commissioning (along with George Armstrong Custer, who was under arrest) to train the incoming class of cadets in leadership and infantry tactics. He had already survived a serious groin wound sustained at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill on June 27, 1862.

When the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia marched toward Maryland and Pennsylvania, the 4th Infantry left its winter camp on June 4 and marched west eight miles to Banks Ford on the Rappahannock River to provide a picketing force. The regiment remained there for nine days before receiving orders to pursue the advancing Confederates. Obediently, the regiment crossed the Potomac River at Edward’s Ferry.

The 4th U.S. Infantry was a regiment in name only when it approached Gettysburg at the end of June 1863. Reduced from 10 to four companies, its total strength was just 230 enlisted men and 32 officers, counting the regimental staff and band. In actual numbers, there were only 179 enlisted men that could be counted as present for duty. By then, the Army Adjutant General had approved plans to allow regiments to reduce some companies to cadre strength and transfer the privates to other companies. As a result, the 4th Infantry had disbanded Companies D and E in July 1862, and four more companies (A, B, G, and I) in March 1863.

Infantry companies were authorized three commissioned officers. Captain Samuel Sprole was assigned to command Company H on June 11, but he was still on sick leave. First Lieutenant Thomas A. Martin had been under arrest for undetermined causes earlier that spring. He took temporary command of the company in June. Second Lieutenant George W. Dost was a long-service enlisted man prior to being commissioned an officer in February 1863. Second Lieutenant George Williams was temporarily attached to the company from Company I.

Fully authorized strength for a Regular Army infantry company was 82 enlisted men. When Company H departed its winter camp on the Rappahannock River on June 4, it numbered 67 soldiers, but not all of them finished the march. Over the next 29 days, the men covered an average of more than 12 miles per day on nine separate occasions. The longest marches were 18 miles per day. Heat, fatigue, and combat stress had a significant impact on the company’s soldiers.

On June 26, the company left its camp at Aldie, Virginia, marched through Leesburg, and crossed the Potomac River before halting in Maryland about 12 hours later, having covered 25 miles in constant, drizzling rain. Three sick men were left behind in Frederick, Maryland, following the march. One of the soldiers, Private Pratt Day, was hospitalized in Frederick until early September, then transferred to Fort Columbus in New York harbor, where he died on October 6 from the effects of sunstroke incurred while on the march to Gettysburg.

The Men of Company H

After another 25-mile, 13½-hour march on June 30, the company strength stood at 54 men. Of these 54, over two-thirds were immigrants. Typical of other Regular Army units at this point in the war, the vast majority (26) were from Ireland. Six hailed from Germany and three from England. The other two immigrants came from Canada and France. Sixteen men claimed birth in the United States. New York was home to nine, while Pennsylvania provided three. One man each claimed his birthplace in Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, and Ohio, and one man’s place of birth was unrecorded.

Over 20 different civilian occupations were noted on the enlistment forms: the majority of the men (16) were unskilled laborers; seven men worked in construction; six were shoemakers; and another five were farmers. The most educated men in the company were Private William Hamilton, who listed his occupation as a druggist, and First Sergeant John Rowlands and Private Leon Dandelooy, who were both clerks before the war. Dandelooy often worked as a clerk in the regimental headquarters.

The core of the company was composed of 44 Old Army Regulars from various companies of the 4th and 9th Infantry Regiments, men who had served together in California, Oregon, and Washington Territory prior to the war. They were experienced soldiers with an average age of about 30 and just over six years in service. Three soldiers had been in the Army at least 15 years. Another three were approaching the end of their second five-year enlistment. At least one had fought in the Mexican War. These veterans would bear the brunt of the company’s casualties at Gettysburg.

The other 10 men in the company had either been recruited from volunteer units in late 1862 or recently enlisted. As a group, they averaged only about 7½ months in uniform. They tended to be younger, had minimal training or combat experience, and shared no common bonds with the Old Army veterans. All four of the men who went over the hill on the march to Gettysburg were from this group. The case of Private Adolphus Pickney illustrated the problem of desertion and its consequences. Pickney had enlisted in early 1860 in the 9th U.S. Infantry, and by early in 1862 had transferred into Company H of the 4th Infantry. Just days before the Battle of Second Bull Run in August 1862, Pickney deserted and remained a fugitive until apprehended on March 11, 1863. Tried by a general court-martial and found guilty, he was sentenced to forfeit all pay and allowances and be dishonorably discharged. The court clearly decided to make an example of him to discourage further desertion. The muster rolls for April 1863 record that Pickney was “to be marked indelibly on his left hip with the letter ‘D’; then to have his head shaved and to be drummed out of the service.” Regular Army discipline was exacting and rigorously enforced.

While total enlisted strength stood at 54 on paper, just 43 soldiers marched with Company H onto the field at Gettysburg—barely 50 percent of authorized strength. Two soldiers were on detached service (temporary duty), and eight more were sick in various hospitals. Another soldier, Private Richard Bears, probably the luckiest man in the regiment, received his discharge papers in camp at Union Mills, Maryland, on the morning of July 1. He did not reenlist.

4th Infantry at Gettysburg

When the Battle of Gettysburg started on July 1, V Corps arrived in the late afternoon at Hanover, Pennsylvania, after a hot, tiring march of 15 miles from Union Mills. Sykes, elevated to command the corps, received a peremptory order from army headquarters to bring his corps to Gettysburg without delay. He decided to keep the troops on the road for a few more hours. They finally went into bivouac around midnight, but reveille sounded in the camps at 3 am. The troops were soon on the march again after a quick breakfast, and arrived near Gettysburg around 7 am. They occupied an assembly area on Powell’s Hill, southeast of the town. Since leaving camp at Falmouth, the Regulars had marched an incredible 195 miles.

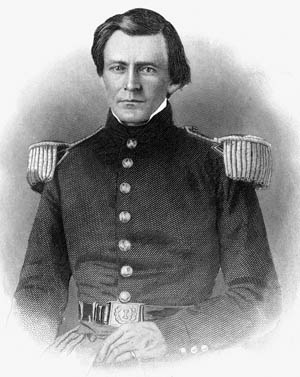

The 4th Infantry, along with the 3rd, 6th, 12th, and 14th U.S. Infantry Regiments formed the 1st Brigade of the 2nd Division. On June 28, Colonel Hannibal Day arrived to take command of the brigade. Almost 60 years old, he had graduated in the West Point class of 1823. Day was originally commissioned in the 2nd U.S. Infantry. He served in a number of operational and administrative postings until June 1862, when he was appointed as the colonel of the 6th Infantry. However, for a number of recent years his questionable health had kept him from an active field command.

Around 1 pm on July 2, the Regulars moved to a new assembly area behind the center of the Union line, where the soldiers dozed, lounged, and talked. It was a brief respite. Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet launched his sledgehammer attack on the Union left flank at 4 pm that afternoon. The Confederates stormed through the Peach Orchard and the Rose Farm and decimated the Union III Corps. Portions of II Corps and all of V Corps were directed to the south to save III Corps from destruction and restore the threatened flank.

The 2nd Division of V Corps set off at double-quick time cross country over fields and fences and panting with the exertions of recent days. While Brig. Gen. Stephen H. Weed’s 3rd Brigade of the division was rushed onto Little Round Top, the two brigades of Regulars deployed on the north slope of that key terrain feature. Colonel Sidney Burbank, commanding the 2nd Brigade of Regulars, formed his brigade into a single line of battle with the 2nd Infantry on the right, followed to the left by the 7th, 10th, 11th, and 17th Regiments. Day’s 1st Brigade formed in column behind the 2nd Brigade with the 3rd, 4th, and 6th Regiments in the first line, followed by the 14th Infantry in the second line, and the 12th Infantry in the third line.

Hell in the Wheatfields: “The Slaughter Was Fearful”

The Regulars were ordered into the Wheatfield to support Caldwell’s division of the II Army Corps. They set off down the slope of Little Round Top at double-quick time and crossed Plum Run, an ankle-deep marshy area about 50 yards wide. The 2nd Brigade mounted Houck’s Ridge at the east side of the Wheatfield, while Day’s brigade adopted a supporting position in Burbank’s rear along the west slope of the valley. As they moved forward, the Regulars received considerable fire from Confederate snipers firing from Devil’s Den on their left flank. The 17th Infantry refused their left flank to provide covering fire. After sheltering momentarily behind the stone wall on the crest of the ridge, the 2nd Brigade then passed through a thin strip of Rose’s Woods before executing a half-left wheel into the open Wheatfield after Caldwell’s division and Schweitzer’s brigade had withdrawn from the field after running out of ammunition.

Attempting to stem Longstreet’s onslaught, Burbank’s brigade was opposed by two Confederate brigades. A heavy firefight ensued, creating great noise, smoke, and rampant confusion. When two further Confederate brigades entered the fight on the Regulars’ right flank and rear, it was quickly realized that they could not hold their position. The noise was so loud that some of Burbank’s men did not hear the order to fall back, and the Wheatfield was swarming with Georgians and South Carolinians inspired by the prospect of victory. By this time, both brigades were receiving fire from three directions in a perfect storm of shot and shell. The hell in the Wheatfield was remembered by an officer in the 11th Infantry as “almost a semi-circle of fire. The slaughter was fearful.”

The Regulars had spent less than an hour in the Wheatfield fight. At the turn of the century, Lt. Col. William F. Fox, New York’s official historian of the battle, wrote, “They moved off the field in admiral style, with well-aligned ranks, facing about at times to deliver their [volley] fire and check pursuit. Re-crossing Plum Run Valley, under a storm of bullets that told fearfully on their ranks, they returned to their original position. In this action the regulars sustained severe losses, but gave ample evidence of the fighting qualities, discipline and steadiness under fire which made them the pattern and admiration of the entire army.”

The Regulars fought their way back 250 yards across the swampy ground, having lost a total of 53 officers and 776 men out of 2,500 engaged in the fight. Day’s brigade, which had occupied a relatively safe supporting position in the initial action, still lost 25 percent of its men. Most of these losses occurred during the withdrawal from the Wheatfield sector. Captain Adams reported that his loss in the 4th Infantry was 10 enlisted men killed and two officers and 28 enlisted men wounded. Unquestionably, the Regulars’ superior discipline and professionalism served them very well in this extremely difficult situation. Less disciplined troops would have folded under the considerable Confederate pressure. A notable absence was the lack of effective artillery support ordinarily coordinated by the Regulars’ commanders. The Confederates now controlled all of the Wheatfield and Houck’s Ridge.

The Regulars remained in their original positions on Little Round Top throughout the rest of the battle, skirmishing periodically with the enemy. On July 5, the entire V Corps left its positions at Gettysburg and set off in pursuit of the Confederates who were now on their way back to Virginia. When the Regulars finally ended the campaign at Warrenton, Virginia, on July 27, they had marched a total of 320 miles since June 1.

Casualties of Company H

Four soldiers in Company H were killed in action on July 2, and nine others were wounded that day, including Second Lieutenant George Williams, who had been attached to the company since May. Of the wounded, four died before August 15. Perhaps because they were Regulars, the backgrounds of some of the dead were recorded carefully.

From Hanover, Germany, Private Christian Abert had been in the Army for almost 15 years and was at the end of his third enlistment when he was killed. He had served in three separate regiments in Texas, California, and Washington Territory. Private Peter McManaman from County Mayo, Ireland, was among the oldest soldiers in the unit at age 42 and had served 14 years. Like Abert, he first enlisted in 1848 but served his entire time in the 4th Infantry. Both are buried in the Regulars’ section of the Gettysburg National Military Park Cemetery.

Private Christian Engers was a cabinet maker from Prussia and had been in the Army for nine years when he was killed. He initially enlisted in 1854 in the 2nd U.S. Infantry and served in Minnesota, and then reenlisted in 1859 into Company I, 4th Infantry at Fort Steilacoom in Washington. Engers was one of the 37 privates transferred into Company H in March 1863. Private Roger McDonald, a shoemaker from Ireland, enlisted in the 9th Infantry in early 1860 and was among the group transferred into the 4th Infantry in January 1862. Both are also buried at Gettysburg.

Private William Becker, a carpenter from Marburg, Germany, was shot in the left chest on July 2 and died of his wound about a week later. Becker presents an unusual case. He enlisted in 1852 but deserted in California in July 1853 along with 15 other men. Becker probably didn’t find his fortune in the gold fields but remained a fugitive for seven years before surrendering on November 21, 1860, at Fort Vancouver. He was tried by courtmartial, sentenced to one year at hard labor, and transferred into Company H to make good the time he lost to desertion. His record indicates that his subsequent service was honorable. Private Michael Carroll was shot in both legs on July 2 and died of his wounds on July 5. He had had about nine years in the army when he marched into the Wheatfield. Carroll, from Tipperary, Ireland, had served in the 4th U.S. Artillery and the 9th Infantry before his transfer to Company H in early 1862.

Private William Hamilton was wounded in the left leg and died on July 22 from complications following amputation. A pharmacist from Maryland in civilian life, Hamilton was called a “hospital steward,” an unofficial company medic, by his fellow soldiers. Corporal Richard Patterson was wounded in the right arm on July 2. He was treated on the field and evacuated to a general hospital in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Medical records indicate he contracted an infection there and died on August 15. His comrades, engaged in pursuing Lee’s army back to Virginia, did not find out about his death until September.

Private David Dunbar was the first man wounded in the entire regiment, according to Lieutenant Dost. Dunbar was shot in the left leg, the bullet “fracturing both shin bones, leaving the leg entirely useless,” according to a surgeon’s report. After treatment in a number of hospitals in the army medical system, Dunbar was transferred to the General Hospital at Fort Columbus on Governors Island in New York harbor, where he was discharged for disability in January 1864. He died on June 23, 1926, at the Soldiers’ Home in Washington, D.C., and was buried in the nearby U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery.

Corporal Martin Kenna was 40 years old with almost 10 years in the army when he was wounded. Kenna survived and was later promoted to sergeant. Private George Farnham received a shell wound, causing a severe bruise to his left foot, but was able to return to duty in late July. Records do not reveal how Private Eugene Mahoney was wounded, only that he was discharged in 1864 at the end of his five-year enlistment.

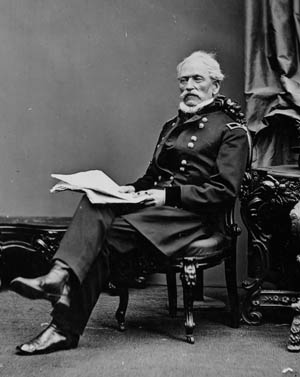

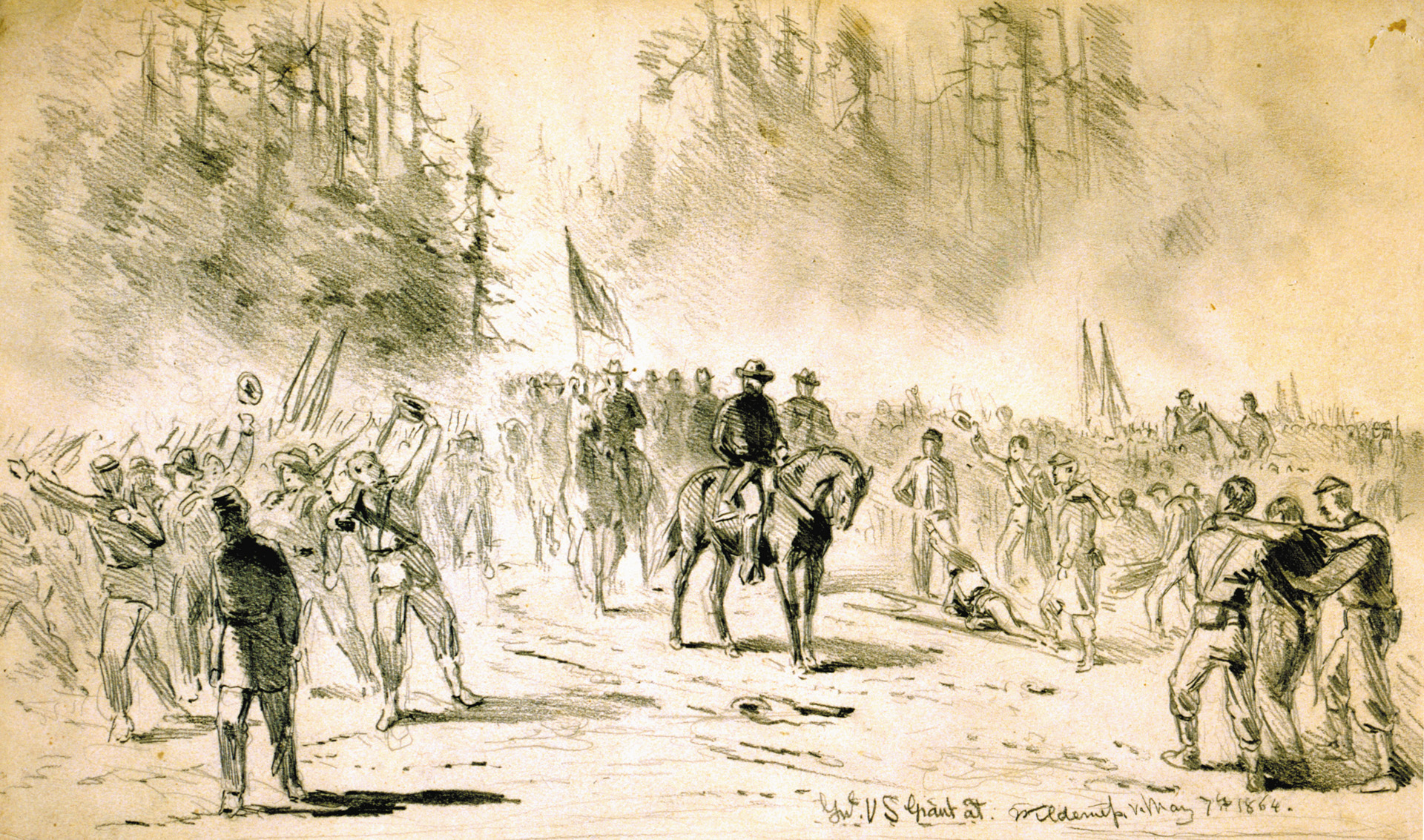

On August 14, the 4th Infantry embarked at Alexandria on the steamship W.P. Clyde to New York City to help quell the ongoing draft riots. Company H had more than 40 men on its rolls from September 1863 to April 1864, when most were attached to Company K. In the spring of 1864, the regiment was transferred to Virginia to participate in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland campaign. Assigned to Brig. Gen. James Ledlie’s brigade in the IX Army Corps, the regiment lost 12 men killed in action, 35 wounded, and 35 missing by the end of May 1864. The following month, the 4th was posted as headquarters guard for General Grant at City Point, Virginia, where it would serve out the remainder of the war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments