By Jon Diamond

Bernard Edward Fergusson was born on May 6, 1911, and completed his public school education at Eton. A graduate of the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, he received his commission into the Black Watch Regiment. His regimental service ensured that he would meet his superior officer in the Black Watch, Archibald Wavell, with whom Fergusson would serve as aide-de-camp (ADC) in Palestine during the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in the British Mandate.

At the outbreak of World War II, Fergusson was a brigade major in the 46th Infantry Brigade prior to becoming a general staff officer (GSO) in the Middle East under Wavell, who was now Commander-in-Chief Middle East. When Wavell was dismissed from this position in June 1941, after suffering defeat at the hands of German General Erwin Rommel, he was transferred as Commander-in-Chief India, exchanging positions with General Sir Claude Auchinleck. Fergusson accompanied his Black Watch superior officer to Delhi, joining Wavell’s General Headquarters (GHQ) Staff there.

Fergusson wrote of the long association between the two officers, “I shall be grateful all my life for the fortunate chance that brought me into his orbit [Wavell’s] from the age of 23 until his death, when I was just 39.” In his capacity as a staff officer to Wavell, Fergusson would interact with another of the Field Marshal’s protégés, eccentric Brigadier Orde Wingate.

One observer described Fergusson as a “monocled Old Etonian from the Black Watch with a patrician drawl.” He was Wavell’s first ADC and was to have quite an orthodox military career including being an instructor of cadets at Sandhurst, a student at the Staff College at Camberley, and then a junior intelligence officer in Palestine, where Wingate held a senior post in Wavell’s intelligence section during the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939. During World War II’s early campaigns, Fergusson was a liaison officer with the Turks in Wavell’s Middle East Command, as well as a forward observation officer with the Free French during the Syrian campaign against Vichy and the Luftwaffe in mid-1941. Fergusson was also a regimental officer in Tobruk.

During the British retreat through Burma in the spring of 1942, Fergusson’s Black Watch was relieved from its Cyrenaican bastion and rushed from Syria with the intent of reaching Rangoon before its fall. However, the rapidity of the British collapse in Burma meant that Fergusson and his regiment would be too late to do anything meaningful there, and so it began training in Bombay. By virtue of Fergusson’s planning experience in the Middle East, he was transferred to the newly designated Joint Planning Staff (JPS) at Wavell’s GHQ in Delhi in May 1942, to explore the possibility of Burma’s reconquest amid the horror of the British Burma Army’s retreat toward Kalewa on the Chindwin River.

Joining the 77th Indian Brigade

While at the JPS at GHQ, India, Fergusson heard any number of people offering suggestions for the retaking of Burma, but only one that made a real impression, “a broad-shouldered, uncouth, almost simian officer who used to drift gloomily into the office for two or three days at a time, audibly dream dreams and drift out again … as we became aware that he took no notice of us … but that without our patronage he had the ear of the highest, we paid more attention to his schemes. Soon we had fallen under the spell of his almost hypnotic talk; and by and by we—some of us—had lost the power of distinguishing between the feasible and fantastic. This was Orde Wingate.”

Fergusson, like Wingate, had a fondness for the Near East, and like him, too, had been engaged in intelligence work in Palestine, where they met in August 1937. Prior to Burma, the paths of Wingate and Fergusson crossed again, when the former was organizing his campaign with Gideon Force in Ethiopia. Fergusson had not been happy in Delhi, where he had had the only job in which he found himself “continuously and thoroughly miserable.” He was vexed by GHQ, not only for himself, but also for his former chief, Wavell.

Fergusson recalled the brilliant staffs that had served under Wavell in Aldershot and Cairo and compared them to those in Delhi. Fergusson was a man of action who longed to “escape the secretariat for battlefield bravado.” Thus, when Wavell endorsed Wingate’s plans to form a Long Range Penetration (LRP) unit, Fergusson was only too glad to get away. When Fergusson joined Wingate’s 77 Indian Brigade in the autumn of 1942 for Operation Longcloth in Burma set for early 1943, Wavell felt that his protégé from the JPS “had reached his real heart’s desire.”

Fergusson had observed that no one at GHQ Delhi seriously believed in Wingate’s ideas except Wavell, and 77 Indian Brigade was derisively referred to “the Chief’s [Wavell’s] private army.” However, in his memoirs Fergusson wrote, “I was almost the only person in J.P.S. with patience to listen to him, and was therefore encouraged to deal with him whenever he showed up.”

After lamenting his fate at JPS and requesting a transfer back to the Black Watch at monthly intervals, Fergusson, in September 1942, was granted his return to regiment, currently on internal security duties in Bihar, India. However, Wingate again appeared at JPS and at once said, “You’d far better come and command one of my columns.”

When Fergusson arrived at Wingate’s jungle training camp at Malthone, another officer approached him and said, “My advice to you is to turn round and go straight back to Delhi. Wingate’s crackers, and I’m off.”

Operation Longcloth

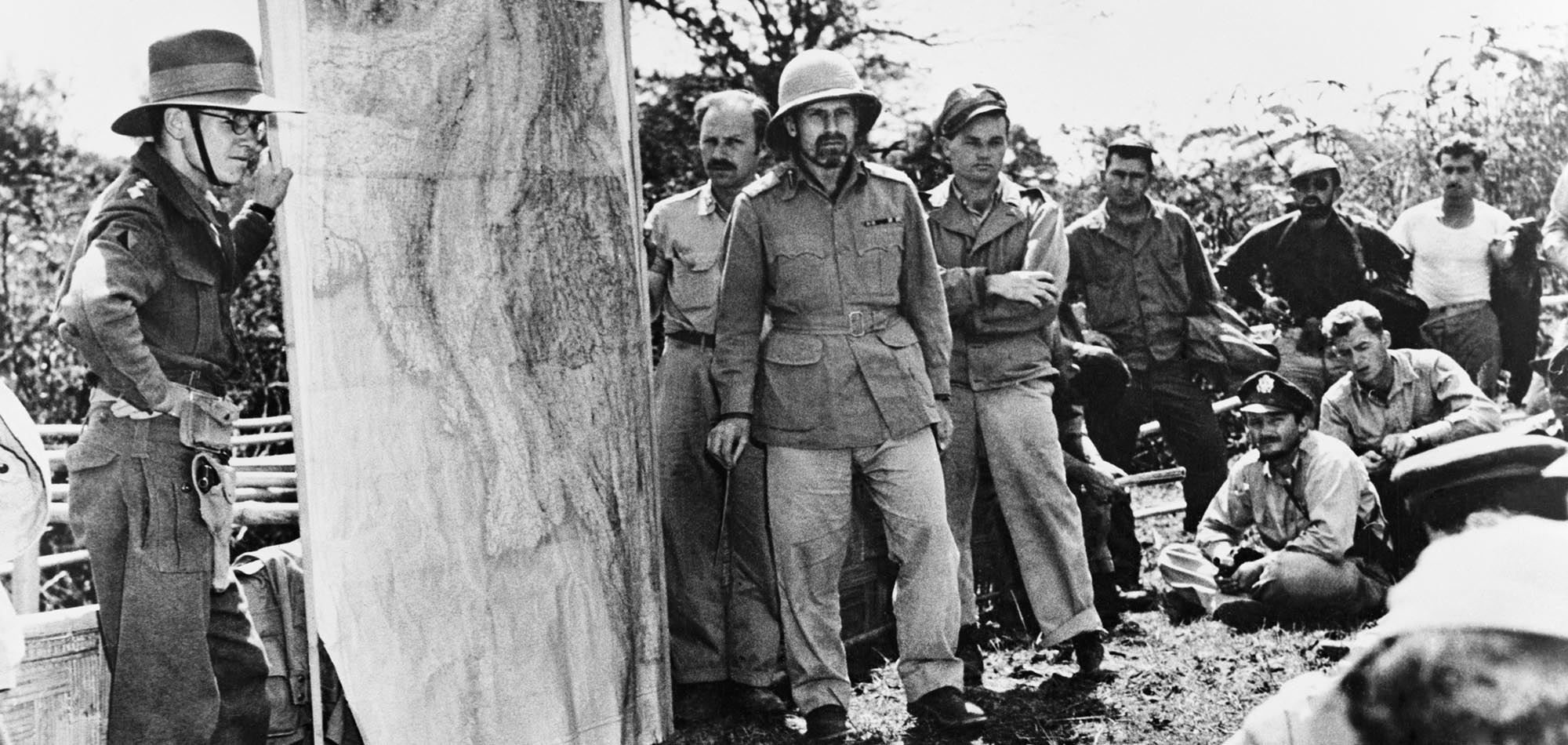

For Operation Longcloth, 77 Brigade began its march on February 8, 1943, in a southeasterly direction from Imphal to Moreh on the Assam-Burma border. Once inside Burma, the brigade was divided into two groups. The Northern Group consisted of the Brigade HQ, the Burma Rifles HQ, HQ 2 Group, and Columns 3,4,5,7, and 8. Fergusson commanded Column 5. The Southern Group was composed of HQ 1 Group along with Columns 1 and 2. The total strength of the Northern Group was 2,200 men, while the Southern Group had 1,000 men. The British 77 Brigade was advancing between the 18th and 33rd Imperial Japanese Army Divisions. For Wingate’s 3,000-man incursion into Burma, the strategic aim was to disrupt the lines of communication of these two Japanese divisions, primarily through the demolition of the Burmese Railway which supplied them, as well as test his long-range patrol philosophy and tactics.

On February 13, the main body (Northern Group) crossed the Chindwin River at Tonhe, where the river was only 400 yards wide. The entire Northern Group had crossed the Chindwin by February 18.

The Northern Group, under both Wingate and Lt. Col. S.A. Cooke, moved over rough terrain for two weeks undetected by the Japanese until they concentrated near Pinbon and north of Pinlebu. Columns 3 and 5 of the Northern Group, led by Major Mike Calvert and Fergusson, respectively, were to head for the Wuntho-Indaw section of the Burmese Railway, which ran north-south from Myitkyina to Mandalay, and cut the line in as many places as possible. The other columns were to search for and engage the Japanese concentrated near Pinbon and Pinlebu in an attempt to conceal the thrust to the railway north of Wuntho by Calvert and Fergusson.

Controversial Decision to Cross the Irrawaddy River

The Chindits were about to achieve a great success under the aegis of Calvert and Fergusson. By March 6, the railway line had been cut in 70 places by Calvert’s Column 3, which had also destroyed two bridges, one of which had a 300-foot span. Fergusson’s Column 5 destroyed a railway bridge about 10 miles northeast at Bongyaung, with its 40-foot center span dropping into the river below. Fergusson also blocked the railway line by dynamiting a gorge outside Bongyaung. This section of the railway wound through the middle of northern Burma, providing the Japanese with an excellent line of supply and reinforcement in inhospitable terrain. Despite this demolition, the Japanese, with the help of forced labor, restored the railway line within four weeks.

Some have argued that Wingate’s next decision to cross the Irrawaddy River was extremely difficult and dangerous, producing the greatest number of casualties. Throughout his career, this difficult event is the one for which he is most blamed. Calvert and Fergusson also wanted to cross the great Burmese river. The specific operational dilemma for Wingate was whether crossing the Irrawaddy was more hazardous than taking his depleted columns in a reverse course through jungle country, which was now teeming with Japanese patrols. Finally, it must be stated that when Wavell reapproved Operation Longcloth, his orders specifically provided for 77 Brigade’s crossing of the Irrawaddy as long as it appeared possible and to evaluate and test the limits of long-range patrols.

On March 10, Column 5 under Fergusson crossed the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing, but they were discovered by the Japanese. The inhabitants of Tigyaing welcomed Fergusson’s column and provided boats for their crossing of the Irrawaddy. Wingate signaled Fergusson on March 23 to meet him at a supply drop rendezvous in the vicinity of Baw, where 77 Brigade fought its last pitched battle as a cohesive unit, albeit under adverse conditions and with only an incomplete airdrop.

Fergusson’s Column 5 had little water and food while between the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers. They sucked fluid from bamboo shoots and butchered mules and other small animals for meat. On March 24, Wingate was ordered to recross the Irrawaddy and withdraw westward to the Chindwin. The Japanese presence on the west bank of the river and only a few boats present made this prospect a daunting one. Ultimately, dispersal of the still extant columns into smaller groups was carried out. Fergusson finally met with Wingate on March 25 and suggested that the Chindit force would fare better by remaining intact with its animals and heavier weapons. However, Wingate vetoed this plan, arguing that the force was too large for air resupply.

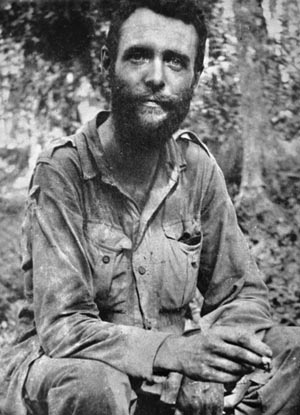

Within the Shweli loop, where his vulnerability was gravest, Fergusson attacked Hintha, halfway between Baw and Inywa, in one of Wingate’s patented feints, losing his radio communications in the process. Unfortunately, this further separated Fergusson from the main body, as well as from another Royal Air Force supply drop. Ultimately, Fergusson’s depleted ranks, after a treacherous crossing of the Shweli, staggered on for another 15 days until they reached the Chindwin on April 24 and finally arrived at Imphal two days later. Column 5 had only 95 survivors from an original roster of 318 men.

“What Did We Accomplish?”

Fergusson summed up Operation Longcloth: “What did we accomplish? Not much that was tangible. What there was became distorted in the glare of publicity soon after our return. We blew up bits of railway, which did not take long to repair; we gathered some useful intelligence; we distracted the Japanese from other minor operations, and possibly from some bigger ones; we killed a few hundreds of the enemy which numbers 80 million; we proved it was feasible to maintain a force by supply dropping alone…. But we amassed experience on which a future has already begun to build.”

In the introduction to Fergusson’s book The Wild Green Earth, the now brigadier of Special Forces’ (3rd Indian Division) 16th Brigade clearly states what Wingate’s original plan was for Operation Thursday, which commenced in early March 1944.

“To introduce his Special Force into the area of Indaw, the northernmost communications centre of any importance in upper Burma,” wrote Fergusson, “part of the Force was to go in by air; my own Brigade by marching. The Force was then to seize and hold an enclave into which two ordinary divisions were to be flown, and towards which the Corps around Imphal was to advance.

By this means, not only would the Japs opposing Stilwell in the north be cut off, but we should have delivered the British-Indian divisions from the defiles in which they had so long been confined, and put them in a bridgehead from which they could advance on a broad front…. It was long afterwards—indeed, until after this book was completed—that I learned from General Sir William Slim, the commander of Fourteenth Army, that the Plan was modified long before the fly-in of Calvert’s and Lentaigne’s Brigades and even before my own Brigade set off on foot. It seems that the Japanese advance across the Chindwin which materialized in March of 1944 was foreseen, and that General Wingate was warned that the ‘follow-up’ could not take place. This modification in the Plan was not made known to General Wingate’s Brigade commanders. Perhaps he thought it would discourage us; perhaps he hoped to create such a favourable situation that the original Plan would be switched on again.”

Operation Thursday: The Second Chindit Campaign

As early as January 16, 1944, Wingate provided evidence to Mountbatten that an Imperial Japanese Army move up to the Chindwin River was preparatory to an offensive against the Imphal/Kohima Plain in Manipur. His prescient views also offered that the Japanese would be compelled to use the “long bad vulnerable roads of Burma” and that this offensive would be “strong and damaging and that before it was overcome 11th Army Group might have to face the temporary loss of all Manipur.”

This prediction was quite accurate as events unfolded. On March 14-15, three Japanese divisions invaded Assam from north of Homalin and from the center of their Chindwin front, launching Operation U-Go. Fergusson’s firsthand account of Wingate’s original plan in full knowledge of the looming Japanese offensive into Assam reminds the reader that with Wingate the distinction between brilliance, exhibited by such an audacious plan for the reconquest of central and northern Burma, or madness, as Wingate’s critics lambasted him for proposing the second Chindit mission as the fulcrum for Burma’s recapture, was always debated. Fergusson clearly believed in the former description of Wingate’s strategic thinking about the second campaign in Burma, Operation Thursday.

To get to the Chindwin River, Fergusson’s 16th Brigade departed from Ledo in India on February 5, 1944, and climbed over and down the Paktai Hills along General Joseph Stilwell’s Ledo Road. Fergusson’s brigade crossed the Chindwin unchallenged on February 28 northeast of Hkamti, courtesy of a decoy crossing south of the town. Fergusson’s boats and engines for the Chindwin crossing had been landed by glider near the river while the decoy party was flown in by light aircraft.

The brigade’s destination was Indaw and its airfield complex some 300-400 miles to the south. On March 10, when 16th Brigade approached Haungpa, Fergusson sent two columns of Chindits to capture Lonkin from the south. On March 12, Fergusson was ordered to capture the Indaw airfields and the surrounding communications and supply depots and establish an airfield that would be transformed into the stronghold named Aberdeen. Thus, at peak marching rate, Fergusson’s 16th Brigade moved south, parallel with and west of the railway toward Indaw.

Japanese Fifteenth Army commander General Renya Mutaguchi realized the threat to his lines of communication, so he ordered the 18th, 56th, and 15th Divisions, the latter heading west for the Imphal offensive, to send one battalion each to the Indaw area to comprise an anti-airborne brigade. Furthermore, General Torashiro Kawabe, commander of the Burma Area Army and Mutaguchi’s superior, brought up the 24th Independent Mixed Brigade from southern Burma along with elements of the 2nd Division and placed these troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Yoshihide Hyashi of the 24th Independent Mixed Brigade, who assumed command at Indaw on March 18.

Unfortunately, Brigadier Walter Lentaigne’s battalions from the 111th Brigade were late in their longer march from their landing field at Chowringhee and thereby failed to block the Japanese reinforcement route from the south before Fergusson’s brigade could attack Indaw. By the end of March, there were nearly 20,000 Japanese troops in the Indaw-Mawlu area. On the positive side, these crack troops were now unavailable for the attacks on Imphal and Kohima. Thus, the Chindits, in approximately division strength, eventually confronted the consolidated strength of two Japanese divisions while the whole of Slim’s Fourteenth Army had only three and a half divisions to encounter.

Orders to Attack Indaw

On March 19, Fergusson established a base at Taungle, but after meeting with Wingate it was moved near to Mahnton, where Aberdeen’s Dakota airstrip would be constructed beginning on March 20. Aberdeen, unlike the other strongholds, was never attacked by the Japanese except by air. After the 300-400 mile overland march, Fergusson’s troops were widely scattered and requested time to concentrate. Since Wingate was aware of the massive Japanese reinforcements pouring into the Indaw area, he ordered Fergusson to attack with three battalions on the night of March 24, which temporally corresponded with Wingate’s fiery airplane crash and death.

The Japanese had expected an attack and had 10 battalions for Indaw’s defense. Fergusson wanted some reinforcements from Aberdeen, which included elements of the Chindits’ 14th Brigade, but Wingate, without informing Fergusson, had instead ordered these troops south to interdict Japanese supplies leading to the Chindwin. With Wingate’s death, there is much speculation as to who, ultimately, originated the plan for 14th Brigade to attack the rear of the Japanese attacking Imphal. One account is that when Wingate’s brigadier, Derek Tulloch, informed the Chindit leader that Slim was now seriously considering taking the reserve Chindit brigades (14th and 23rd) into the Fourteenth Army for the defense of Imphal/Kohima, Wingate immediately flew to see Slim at Comilla.

A compromise between Slim and Wingate was struck in which the 14th Brigade would not be incorporated into the Fourteenth Army, nor would it be used to help Fergusson at Indaw. Elements of the 14th Brigade would instead be sent about 60 miles southwest of Aberdeen to sever Japanese communication lines for the U-Go offensive from the rear. Thus, the defense of Imphal/Kohima was to occur at the expense of weakening Fergusson’s assault against Indaw. Fergusson, to his credit, continued to use sound military principles and ordered an RAF raid on a Japanese supply dump near Indaw West airfield after his 16th Brigade Chindits discovered that it was a major ammunition dump for the Imphal/Kohima offensive.

Fergusson’s Three Mistakes at Indaw

In his memoirs about Operation Thursday, Fergusson stated, “I made at least three mistakes at Indaw. One was in not insisting on a rest for my troops before we assaulted. One was in failing to assess accurately, after all the practice I had had, the Jap reaction to the news they must have had of my approach. The third, and the least excusable, was in losing touch with my columns. There were good reasons for all three, but all three were bloomers.”

Fergusson’s plan called for Indaw to be attacked from the north with four columns, while additional columns would each block reinforcements into Indaw from the west and south. In the end, 1,800 weary Chindits would attack Indaw after “an arduous march of 400 miles without so much as a day’s rest.”

A variety of things went wrong. First, two columns from a different Chindit brigade, probably heading for Pinlebu, had crossed Fergusson’s attack front using an imaginary attack on Indaw as cover for their own brigade’s primary objective. As Fergusson noted later, “It was another example of the old business of excessive security defeating its own object; the concealment of the main plan from subordinate commanders resulting in its chances of success being compromised.”

Another issue was the scarcity of water on the eastern side of the Meza River. Fergusson had experience fighting without water.

He wrote, “In Syria, in 1941, I had seen a company of Punjabis pinned to the forward slope of the Jebel Madani, south of Damascus, in the month of June—a hillside studded with lava, and throbbing in the sun. Fourteen men had died of thirst on that day. With this memory behind me, I was determined, whatever else I did, to make sure of a firm hold on a water supply; and, if necessary, to get a footing on the Indaw Lake before anything else.”

In fact, the Japanese knew that Fergusson was to attack from the north and that “the battle would be a battle for water.”

Finally, Fergusson’s synchronization of his attacking columns went awry when an errant column of his brigade stumbled into the Japanese north of Indaw, setting off a firefight. All of these mishaps now coincided with 72 hours of thunderstorms, which deprived Fergusson of wireless communication with his columns as they forayed toward Indaw Lake, which bisected the Indaw West and Indaw East airfields, north of Indaw town and astride the railway.

As Fergusson recalled, “Thus, out of my six columns engaged, three had lost their power to strike; two were fully committed; the only one intact way … blocking the road between Indaw and Banmauk, at the 20th milestone from Indaw.”

“The Birds Had Flown”

During this phase of his attack on Indaw Lake, Fergusson contemplated a retreat to the Kachin Hills to preserve his force and was also informed of Slim’s diversion of 14th Brigade Chindits to the Taung and Meza Valleys, and nowhere near Indaw. Fergusson ordered the remnants of his columns to return to Aberdeen, where they could refit after, he noted, “they had had a hard battle on top of a hard march of seven weeks, carried out on short commons and culminating in several days of insufficient water.”

Fergusson added that he was “naturally disappointed at my failure to capture Indaw, although less so when I found that it was no surprise to my colleagues or to Force Headquarters. Apparently even Wingate had said that he wasn’t optimistic about it.”

After refitting at Aberdeen for over a month, Fergusson attacked and captured the Indaw West airfield on April 27. He noted, “This second approach to Indaw was an anti-climax, and for two reasons. First, just before we went in we were told that even if we captured the airfield of Indaw West, no troops, no divisions would be available from India for flying in: all hands and the cook, it seemed, were tied up in the great battle for Manipur. We were to capture the field for two or three days and then to abandon it…. Secondly, it was early apparent that the birds had flown. The Queen’s got right on to the airfield without a shot being fired.”

Fergusson was later ordered to fly out to India from either Aberdeen or Broadway, the latter of which was the initial Chindit landing field in early March. Fergusson arrived by plane in India on May 3, 1944.

Fergusson After the War

On which side of the postwar literary debate over Wingate does Fergusson rest? In the book Beyond the Chindwin, his sentiments are quite unambiguous: “By some, chiefly journalists, he has been idealized; by others, chiefly professional rivals, he has been decried. His was a complex character, but two things are sure. First, he was a military genius of a grandeur and stature seen not more than once or twice in a century. Secondly, no other officer I have heard of could have dreamed the dream, planned the plan, obtained, trained, inspired and led the force. There are men who shine at planning, or at training, or at leading: here was a man who excelled at all three, and whose vision at the council-table matched his genius in the field.”

Fergusson became the Director of Combined Operations from 1945 to 1946. After a failed attempt in a Parliamentary election, he returned to Palestine in 1946 as a brigadier in a paramilitary capacity to confront a Jewish insurrection there. While in Palestine, he became implicated in the investigation of the death of a Jewish dissident and the possible cover-up that followed, leading to his return to Britain.

During the Suez Crisis in the mid-1950s, Fergusson was put in charge of the psychological warfare component of Britain’s plan to retake the Suez Canal after Egypt’s President Gamal Nasser nationalized it. In 1962, Fergusson was appointed Governor-General of New Zealand. He served there for five years as the last British-born Governor-General. His father and both of his grandfathers had been governors of New Zealand. In 1972, Fergusson was granted a life peerage as Baron Ballantrae. He died on November 28, 1980, after serving as chancellor of the University of St. Andrews for seven years.

Dear Alfred,

Thank you for your email contact via my website in relation to Captain Talmadge and John Hla Shein. I am afraid that I know very little about your father-in-law and his service during the war. He was a member of the 2nd Battalion, the Burma Rifles in 1944 and it is likely that he served on the second Chindit expedition into Burma which began in March 1944. I do know that he went on to serve with the Karen Army after the war and reached the rank of Adjutant in 1947.

I have attached a copy of the photograph you mention of the Burma Rifles Officers at Dehra Dun in India in 1944, which shows both Captain Talmadge and John Hla Shein.

As you may have already seen, there is a short page devoted to John Hla Shein and his experiences in Burma where he was awarded the Military Cross medal. In case you did not locate this, here is a link:

https://www.chinditslongcloth1943.com/john-hla-shein.html

I would be very interested to hear any details you have about either man and his military pathway in the war and afterwards. I do not even know Captain Talmadge’s first name other than it begins with the letter D. If you have any photographs of the two men that you would like to scan and send to me, it would be my honour to add these to the website going forward.

As you will understand, the men of the Burma Rifles were very important in both Chindit expeditions, providing good knowledge of the country, guiding the British troops through the jungles and communicating with the various villages along the way organising support, food and boats to cross the large rivers such as the Chindwin and Irrawaddy.

Thank you again for your message and best wishes.

Steve Fogden