By John Domagalski

Shortland Harbor was bustling with activity during the late morning hours of December 7, 1942. A group of warships were slowly getting underway, making for the open sea. The anchorage, positioned in the northern portion of the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific, was the home to a forward operating base of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

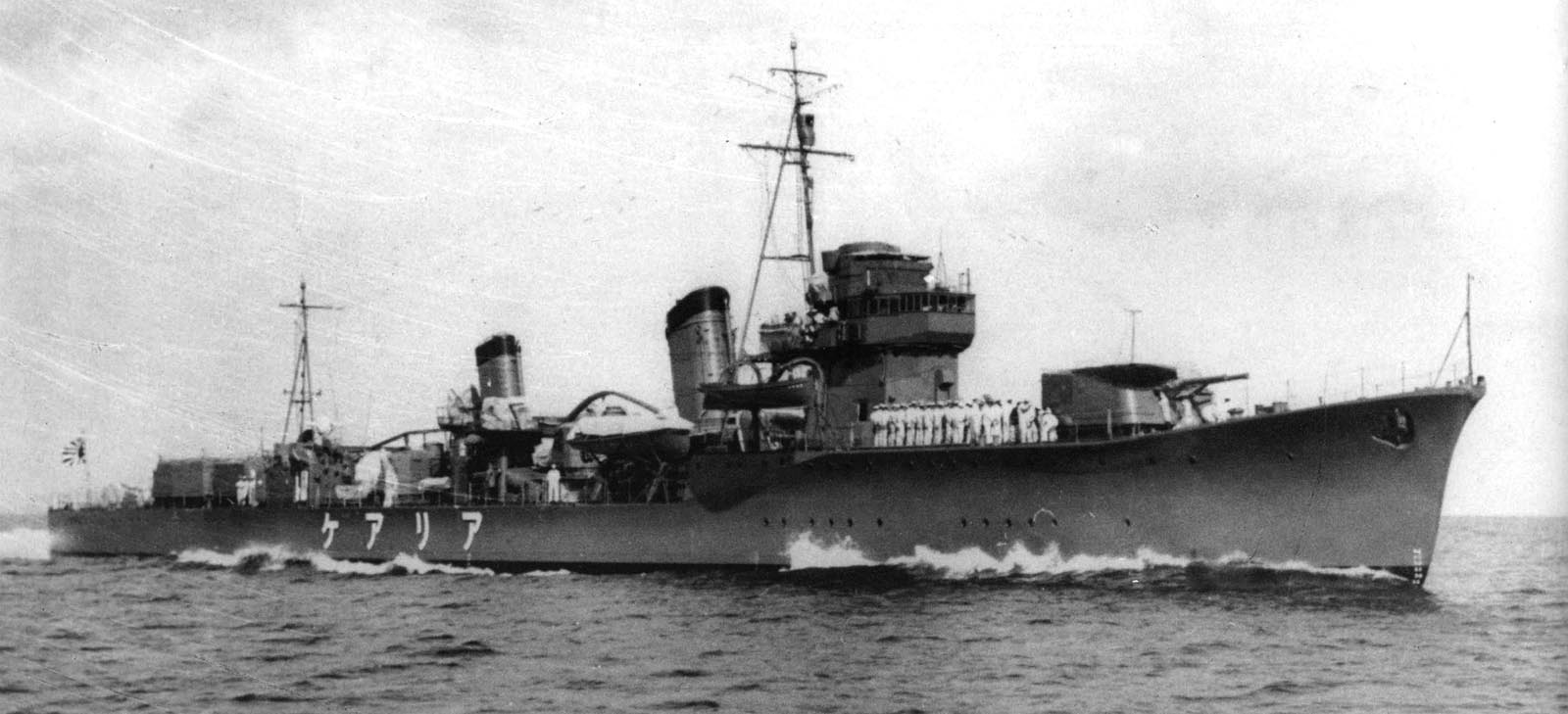

Eleven destroyers departed by 11 am under the command of Captain Torajiro Sato. Their destination was the embattled island of Guadalcanal, located more than 300 miles to the southeast. American and Japanese forces had been struggling for control of Guadalcanal since American Marines landed on the island in early August. The intense battle raged on land, in the air, at sea, and in supply chain logistics.

Intercepting the “Tokyo Express”

The Japanese were slowly losing the fight in all aspects of the campaign. The Imperial Navy, reeling from a series of disastrous naval defeats in November, had been unable to deliver supplies to the beleaguered soldiers on the island using traditional transportation methods. Naval commanders instead devised an innovative plan using destroyers and drums to transport supplies. American sailors dubbed the supply runs the “Tokyo Express.”

Heavy metal drums, normally used for oil or gasoline, were cleaned and sterilized before being partially loaded with food and medical supplies. An internal air pocket was left in place to ensure buoyancy. The containers were placed on the decks of destroyers for the voyage south and tied together in clusters of up to 10. Each warship could hold between 200 and 240 drums. Three destroyers, carrying no drums, served as escorts for the night.

Sato’s force was known as the Reinforcement Unit because of the nature of its mission. He had to rely on the speed of his destroyers to make the run to Guadalcanal, hopefully undetected, arriving under the cover of darkness. The drum clusters were then to be tossed over the side in the direction of land once at a designated drop point on the western end of Guadalcanal. Personnel ashore were to use ropes to pull the drums to the beach. Sato’s force would then depart the area at high speed for the return trip to Shortland.

Much of the voyage south was through a narrow body of water known as the Slot. Lined with parallel rows of islands on each side, the passage led directly to Guadalcanal. American planes regularly roamed the area looking for targets, while coastwatchers—Allied spies—were positioned on various islands on the lookout for Japanese ships.

Sato hoped to be able to slip through the area undetected. Twelve land-based Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter planes and eight seaplanes provided an umbrella of air protection part of the way down the Slot. An alert coastwatcher, however, spotted the ship movement and radioed the information to the Allied command.

The warning sent American airmen on Guadalcanal scrambling to get planes into the air. The Japanese fighters turned back at 4:25 pm, leaving only the eight floatplanes for air cover. The Reinforcement Unit was attacked by 13 American dive bombers a mere 15 minutes later. The strike was beaten back with the loss of several attackers, but not before one Japanese warship sustained damage.

A near miss bomb killed 17 sailors aboard Nowaki. It left the destroyer with a flooded engine room and dead in the water without power. She left the formation under tow by Naganami with Ariake and Arashi acting as escorts for the return trip to Shortland. Sato pressed on toward Guadalcanal with his remaining seven ships.

Planning a Nighttime PT Boat Raid

As the planes tangled with the Tokyo Express over the Slot, American sailors on the small island of Tulagi near Guadalcanal began formulating a plan of action. No large warships were in the area to meet the approaching enemy ships. The only available weapons were PT boats.

The patrol torpedo boats—PT boats for short—were among the newest and smallest warships in the United States Navy. Measuring just 80 feet in length and weighing about 50 tons, the boats’ main weapons were torpedoes and speed. The first contingent of boats arrived at Guadalcanal in October 1942. Their mission was to patrol the waters of Iron Bottom Sound in search of Japanese ships. The body of water, located just off Guadalcanal, had been the scene of a series of fierce naval battles in recent months.

Officers at the Tulagi PT base worked quickly to devise an operational plan for the night. The coastwatcher’s warning, coupled with the air attack and additional aerial reconnaissance reports, helped to narrow the Japanese estimated time of arrival. The situation on land dictated that the supply drop point would likely be somewhere between Cape Esperance on the northwestern tip of Guadalcanal and Tassafaronga to the east.

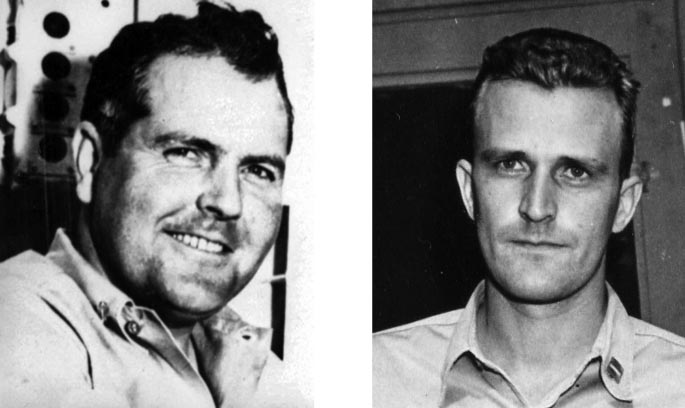

Eight PT boats were available for the night’s mission. The boats were commanded by Lieutenant Rollin Westholm. The leader of Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Two, Westholm had arrived in the area only weeks earlier. This would be the first action for Westholm and his flagship, PT-109. Although the PT boat would later become famous for her final skipper—future President John F. Kennedy—she was currently just one of many small torpedo boats operating on the front lines of the South Pacific.

Three Patrol Groups

The PT boats moved across Iron Bottom Sound toward the west end of Guadalcanal as complete darkness overtook the fading daylight. At the same time, Captain Sato was approaching the area from the north at a high rate of speed. With the Japanese destroyers and American PT boats on a collision course, the setup for the evening battle was complete.

Westholm divided his PT boats into three groups, two patrol and one strike force. Each group would be in a position to provide mutual support to the others once the enemy was located.

The boats were to use radios to stay in contact and report Japanese movements. However, the communication had to be clear and effective if Westholm’s plan was to work. Each PT was equipped with a radio unit mounted in the charthouse. The equipment operated at a very high frequency. The set could transmit voice or Morse code the distance of the horizon or about 70 miles using a 20-foot whip antenna.

The equipment, however, was originally designed for planes and was plagued with problems when used by PTs. Atmospheric conditions, the Japanese use of the same frequencies, and the constant pounding endured by the sets when the boats ran at high speed all combined to make radio communication unreliable. Lacking radar and more advanced radio instruments, the PT boat captains had no choice but to make it work.

The first patrol group, comprised of PT-109 and PT-43, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Tilden, would idle along a line paralleling the Guadalcanal coast from Kokumbona (located just east of Tassafaronga) to Cape Esperance. The second patrol group of two PTs was assigned to the area off the northwest tip of Guadalcanal. This force consisted of Lieutenant Robert Searles in PT-48 and Lieutenant Henry “Stilly” Taylor in PT-40. Both were veteran PT skippers who had arrived at Tulagi with the first boats in October and had since seen plenty of action. The two units were positioned to locate the Japanese either during their initial approach to the area or during their final run to the suspected dropoff point.

The remaining four boats comprised the strike group. Positioned to the south of Savo Island, out of sight of the approaching Japanese, it included Lieutenant John Searles in PT-59, Lieutenant Frank Freeland in PT-44, Lieutenant (j.g.) Marvin Pettit in PT-36, and Lieutenant (j.g.) Lester Gamble in PT-37.

Westholm was comfortable that the plan offered a good chance of success. “The disposition of the boats at the time was considered the best possible to meet all possible approaches of the enemy,” he commented. The squadron commander felt that none of the groups could be outflanked by the Japanese destroyers. The PT boats also had help from above in the form of a floatplane. “One SOC was in air from 11:00 pm to 2:45 am to drop flares as requested.”

The blanket of darkness shrouded the final movements of the Japanese ships. With no additional information available on the approaching enemy, Westholm’s plan remained unchanged in the final hours before the encounter.

The second patrol group and strike force proceeded directly to their assigned positions. Westholm carefully planned the route of his group to maximize its chances of contacting the enemy. “The two boats on the Kokumbona to Esperance patrol had deliberately timed their run to be just east of Tassafaronga headed west at midnight in order that nothing would outflank the boats and to be able to go up the coast and intercept any ships which had slipped by Esperance and were proceeding east along the Guadalcanal coast,” he later wrote.

Lying in Wait For the Tokyo Express

Westholm stood patiently in the small bridge area of PT-109, known as the conn, waiting for the enemy to arrive. His executive officer, Ensign Bryant Larson, was at his side. They looked out into the pitch black night searching for any movement in Iron Bottom Sound. Tension was thick as the pair faced the real possibility of encountering the enemy for the first time. They hoped the enemy would not slip through the various patrol groups.

“The night actions meant limited visibility with patrol sections scattered over a wide area,” Larson later recalled. “Anything we could do to get a better track on the Express and so bring maximum boats to the attack was worth trying.”

The bridge area was small and cramped with a wheel centrally located. An angled instrument panel just above the wheel contained a variety of gauges, including three sets of tachometers and a compass. The area to the right of the control station was dominated by the forward .50-caliber machine-gun tub, but a small open hatch leading to the chartroom below marked the end of the conn area.

By 11 pm, Captain Sato was making his final approach to Guadalcanal. His destroyers were pointed toward the passageway between Savo Island and the tip of Cape Esperance. He unknowingly was on a collision course with at least one group of PT boats.

PT-48 in Trouble

The action started off the northwest end of Guadalcanal at 11:20 pm when lookouts aboard PT-40 and PT-48 spotted a group of ships coming directly toward their position. “These boats at that time were about three miles north-northwest of Cape Esperance and the enemy ships were on a line of bearing, distance one and a half to two miles on a course about 130 degrees true,” Westholm wrote of the initial contact. The course put the enemy ships on a southeasterly heading.

The confrontation that followed developed quickly and then moved at a fast pace. As happened with many PT-boat battles, events often occurred simultaneously or in rapid succession. This battle was fought in the dark of night with occasional flashes of gunfire appearing as speckles against the black backdrop.

Veteran captains Searles and Taylor knew exactly what to do after sighting the enemy. Both immediately turned and added speed in an attempt to gain a firing position ahead of the Japanese ships. One of the engines on PT-48 abruptly failed. The malfunction could not have happened at a worse time. The PT was quickly spotted by alert Japanese lookouts just as the boat started to slow. The lead destroyers immediately opened fire as Searles struggled to get his boat out of harm’s way. He barely cleared the bow of one enemy warship when a second engine failed, slowing PT-48 down to a mere idle. With his main advantage of speed gone, Searles became an easy and inviting target for Japanese gunners.

Alert to his comrade’s predicament, Taylor swung PT-40 around in a tight circle to reverse course. He then ran his boat between the idling PT-48 and the approaching destroyers in a daring maneuver to take the attention away from his ailing companion. Taylor ordered smoke as he opened the throttles to gain speed. PT-40 was headed back into Iron Bottom Sound.

The ruse worked as the two leading Japanese destroyers turned to follow PT-40. Occasional inaccurate gunfire fell close by, but PT-40 was not hit. Taylor poured on speed and soon lost his pursuers as the two destroyers reversed course to rejoin the main group. Searles took advantage of the situation to slowly move to the opposite side of Savo Island, where he dropped anchor close to shore.

The First Attack Run

The captains of the first patrol group successfully radioed out a contact report enabling others to join the action. “The striking force after hearing of the contact deployed and themselves made contact at 11:35 pm,” Westholm later reported. “The enemy force which had originally been coming in fast slowed down at about that time.”

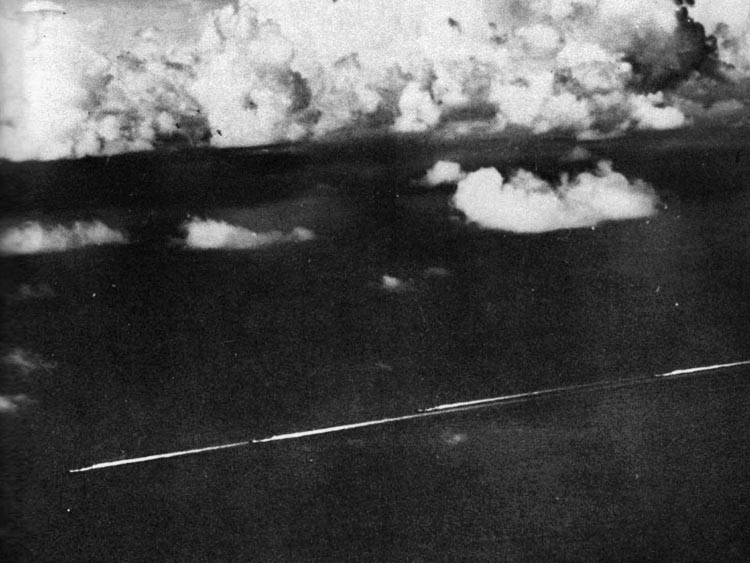

All four boats of the strike force moved toward the enemy for a torpedo attack. Lester Gamble pulled PT-37 into the lead and after closing on the Japanese formation unleashed two torpedoes toward the first destroyer. He was unable to observe any results after turning for cover.

Right behind Gamble was PT-59, which closed and fired two torpedoes. The target ship turned sharply to avoid the fish, but in the process exposed other vessels behind her. Searles believed his torpedoes might have hit one of the distant warships.

PT-59 passed within 100 yards of the destroyer Kuroshio as Searles turned to make his getaway. It was extremely dangerous for the wooden PT-boat to be so close to a powerful warship. Searles told his crew to get ready to fire every available weapon. The PT and destroyer opened fire simultaneously. It was anything but a fair fight as Kuroshio was well over 300 feet long and displaced more than 2,000 tons. Her 5-inch guns could easily blast the PT to pieces with a single hit.

The little torpedo boat could only muster meager firepower in comparison. Bullets from the PT’s machine guns and 20mm cannon raked the destroyer’s deck, gun enclosures, and bridge area. A motor machinist’s mate helped the cause when he leaned out of the engine room hatch to take a few shots with a rifle at the destroyer’s bridge. The barrage of gunfire caused 10 Japanese casualties but no substantial damage.

Gunners aboard the destroyer returned fire at a range so close they could not miss. The PT boat was hit at least 10 times by heavy caliber machine-gun fire. Two bullets pierced one of the gun tubs, setting fire to a belt of .50-caliber ammunition. Gunners Mate 2nd Class Cletus Osborne stayed in the tub and calmly detached the flaming belt of bullets. He tossed it on deck, where the fire was extinguished. The encounter was short and furious, but Searles was able to clear the area. PT-59 miraculously survived the frightening encounter with no casualties, although the captain of Kuroshio reported that he had sunk the intrepid little boat.

Recording Hits on Japanese Destroyers

A short three minutes after the first boat of the strike force attacked, the last two PTs of the group moved in for their torpedo runs. Marvin Pettit conned PT-36 close enough to fire a four torpedo spread at one of the leading destroyers. He sped away untouched believing he scored at least one hit. PT-44 then took aim at one of the last destroyers in formation and fired four torpedoes. Frank Freeland was certain that two torpedoes scored direct hits as he turned his boat away. A destroyer was thought to have been sunk as a result of the encounter after a series of tremendous explosions were observed.

Westholm’s boat was far from the action when the battle started, but it did not take long for PT-109 to speed to the area. “When contact was reported by the boats off Northwest [Guadalcanal] they increased speed to about sixteen knots and proceeded westward up the Guadalcanal coast close in to shore,” Westholm reported of his patrol group’s action. He monitored radio reports from the various PT boats as he moved northwest toward the sounds and flashes of the fight.

After tangling with torpedo boats for almost 25 minutes, Captain Sato attempted to reassemble his destroyers for the final run to the Guadalcanal coast to drop off the supply drums. The two approaching PT boats of Westholm’s group and the sighting of the SOC plane patrolling above were enough to force him to abort the supply mission. Sato ordered his force to withdraw and immediately set a course for the Slot.

Westholm had no way of knowing the Japanese force was already withdrawing as his pair of PT boats continued to move toward the reported action. “The PT’s 109 and 43 continued up the coast and arrived off Esperance about 12:15 am having sighted no enemy ships,” he reported. “At this time the SOC reported a group of enemy ships about seven miles northwest of Esperance.” Westholm gave the order to increase speed and give chase, hoping to get a shot off at the fleeing enemy.

One of PT-109’s three machinist’s mates was stationed in the small engine room near the stern as the boat sped toward the departing enemy. The cramped quarters were loaded with all the machinery needed to keep the boat moving. Westholm’s order to increase speed kept the sailor busy shifting gears to make sure each of the three engines poured on continuous power.

The extra speed did not help. “At about 12:25 am the SOC reported the enemy ships were about 15 miles northwest of Esperance and headed away at high speed,” Westholm reported. It was clear to him the escaping enemy was beyond reach, and the two PT boats returned to their original patrol route.

“Nothing More Was Sighted During the Night”

At about the same time Westholm was giving up the chase, PT-37 was retiring southeast when lookouts spotted a light on land about five miles southeast of Cape Esperance. Lester Gamble requested illumination from above.

“The flare showed a large ship, bow on the beach, and the PT-37 fired her two remaining torpedoes at it,” Westholm explained. “The ship was hit, but it is almost certain that this ship was one which was previously aground.”

The squadron commander’s conclusion was probably correct as four Japanese transports had been run aground several weeks earlier in the area in a futile attempt to deliver reinforcements during the naval Battle of Guadalcanal.

After returning to the Kokumbona-Cape Esperance patrol line, crewmen on PT-109 and PT-43 also saw something on land. “At about 1:15 am a light was observed on the beach one mile southeast of Esperance. Another flare was requested,” a cautious Westholm recalled. It was worthy of further investigation because American sailors had no way of knowing if a supply drop had actually been made during the confusion of the night battle.

“It revealed nothing except some tents or grass huts,” he said of the flare. Westholm decided to leave it for an aircraft to further investigate later. “The plane strafed these but no activity was noted.”

Iron Bottom Sound reverted to silence after the Japanese force escaped to the north. “Nothing more was sighted during the night,” Westholm reported.

The PT Boats Return to Their Stations

The PT boats were scattered among various positions across the area in the immediate aftermath of the action. Westholm tried to keep track of each boat as best he could. PTs 36, 44, and 59 returned to Tulagi after making their torpedo runs.

“The PT-40 reported having trouble with gasoline suction and requested permission to take station southeast of Savo,” Westholm noted. “This was granted.” The boat eventually made her way back to base without assistance.

There was one boat whose position was unknown. “At 4:00 am the PT-48 revealed her position and requested assistance,” Westholm recalled. He was by now certain the Japanese were gone for the night. “The PT-109 and PT-43 proceeded to her position.”

PT-48 suffered engine trouble and fled to the far side of Savo Island and beached early in the skirmish. At about 4:15 am, PT-109 arrived on the scene and pulled the stranded boat free. The three PT boats then returned to Tulagi.

PT-109 moored at the base at 5:20 am. The long night was over for the exhausted crew. Rollin Westholm and Bryant Larson were now combat veterans after experiencing a full-fledged sea battle.

Westholm began work on the required report. He gathered information from his boat captains to determine the sequence of events and the probable damage inflicted on the enemy. Sorting out the facts was a difficult undertaking, but he concluded that one Japanese destroyer was probably sunk and some torpedoes may have hit other ships.

Tokyo Express Deterred

The sinking claim was based on reports and observations from various boats. Of particular note were the two explosions reported by PT-44 in the aftermath of her torpedo run. The timing seemed to be supported by two other observations, including one from Westholm’s own boat. At about 11:50 pm crewmen aboard PT-109 heard “a terrific explosion” to the north, which they attributed to a torpedo hit on a Japanese destroyer. At about the same time, PT-40 was returning to the battle area after slipping away from two chasing destroyers. Her crewmen reported seeing three flashes thought to be torpedo hits in the area between Cape Esperance and Savo Island.

Westholm praised the efforts of three crewmen on PT-59 for their exploits during their close brush with the enemy destroyer. For Cletus Osborne, whose actions with a burning ammunition belt were nothing short of heroic, he called for high commendation. Osborne was later awarded the Silver Star. Westholm also highlighted the actions of two additional sailors who were manning guns during the encounter. “They maintained a high rate of fire on [a destroyer] at close range for a period of several minutes,” he wrote. Westholm thought the pair “should be commended for their skill and valor.”

Contrary to what was reported by the individual boat captains and concluded by Westholm in his official report, none of the 12 torpedoes fired by the PTs hit Japanese ships. A variety of circumstances could explain the explosions reported by the various torpedo boat crews. Some of the weapons may have exploded prematurely, while others could have detonated at the end of their runs. Flashes from enemy guns may also have been mistaken for torpedo hits. An examination of postwar records reveals that no Japanese destroyers were seriously damaged or sunk as a result of the encounter.

The December 7, 1942, battle in which Rollin Westholm led PT-109 and seven other boats against a group of Japanese destroyers did not change the course of the Guadalcanal campaign. The encounter was, however, clearly an American victory. Facing great odds, the brave PT sailors turned back a Japanese supply run that otherwise would have succeeded. It was accomplished without suffering the loss of a single man. Decades later, an American historian wrote that the battle had “cast a different light over the date of December 7 in American naval annals.” As a result of the heroic effort on the part of the PT men, the Japanese supply situation on Guadalcanal remained serious.

Admiral William Halsey, commanding U.S. operations during the Guadalcanal campaign, later reviewed Westholm’s action report and sent a short note to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet. “They are performing heroic services and it is confidently expected that they will set a high record of valor and achievement in the service of their country.”

It was a small victory in the ongoing Guadalcanal campaign fought by brave sailors manning small boats.

Excellent chronology of an important action

The Boats were made of wood but the men were made of steel. God bless our WW2 PT Boat veterans!

This was a tactical draw but a strategic victory for the PT men. Soldiers without supplies are worth no more than (as later events would prove) carriers without planes. Earlier, two other missions were abandoned by the IJN–planned heavy bombardments intended to destroy Henderson Field and the Cactus Air Force. Both were vicious night actions featuring heavy units; both were tactical defeats but strategic victories for the USN, which made the IJN back down. (It’s often forgotten that Navy seamen suffered thrice the casualties of the Marines.) Abandoning Guadalcanal was the start of Japan losing the war: she was on the defensive ever after, with few and futile offensive strikes, growing ever weaker, abandoning thousands of troops on islands they couldn’t re-supply while the USN grew ever stronger and could simply pass them by.

Being an avid reader of WW ll starting in the 1940’s and Guadalcanal being one of my favorite reads the PT boats served in a remarkable way by harassing the enemy and occasionally scoring a torpedo hit.

Thanks for the read, Dave