By Michael D. Hull

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who rode in a cavalry charge in the Sudan in 1898, escaped from the Boers in 1899 and served for six months as a troop leader in the Western Front trenches in 1915-1916, remarked during World War II, “The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

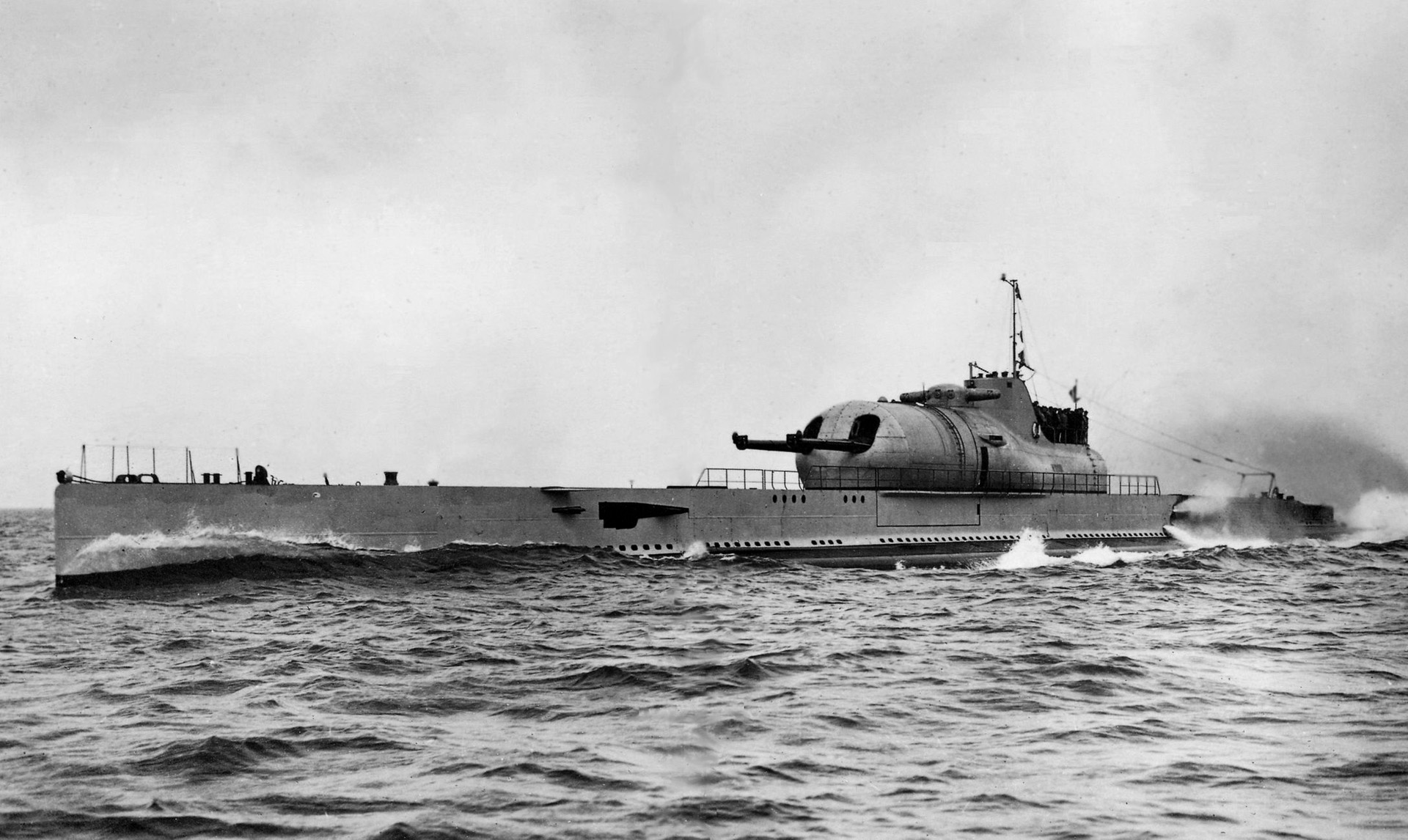

The former First Lord of the Admiralty had good reason to be alarmed. Shipping losses from German U-boats had brought his country to within three weeks of starvation in 1917, and two and a half decades later history was repeating itself with a vengeance. When German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz intensified his offensive against Allied shipping in the North Atlantic late in the spring of 1942, losses rose alarmingly.

The Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy, aided staunchly by units of the Royal Canadian Navy and the U.S. Navy, were engaged in a desperate struggle in which no quarter was given. Dönitz, a former submariner himself, ordered his U-boat commanders, “No attempt of any kind must be made at rescuing crews of ships sunk…. Be harsh, bearing in mind that the enemy takes no regard of women and children in his bombing attacks on German cities.”

The dour, poker-faced admiral, who had hated the British since his capture in the Mediterranean in the last year of World War I, concentrated his 1942 offensive in the “Black Pit” area south of Greenland, where the underwater predators were out of reach of Allied air attacks. Picket lines of U-boats were stationed on both sides, enabling them to attack convoys sailing between Newfoundland and Ireland. Sinkings by Dönitz’s boats mounted, reaching a peak of 117 Allied ships totaling 700,000 tons in November 1942.

Yet all was not lost. When Churchill, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and their military staffs met at Casablanca in January 1943, it had been decided to make the defeat of the U-boats a priority objective. “U-boat warfare takes the first place in our thoughts,” stressed Churchill.

The Casablanca talks led to a convoy conference that March at which it was agreed to pool all antisubmarine resources and also for newly formed U.S. escort carrier groups to be stationed in the mid-Atlantic. Allied scientists, meanwhile, had been busy developing improved antisubmarine weapons and detection equipment to better defend the convoys. This included a microwave radar system that the enemy could not penetrate and a “huff-duff” high-frequency radio direction finder to breach U-boat communications. Escort destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and armed trawlers were fitted with antisubmarine mortar bombs called hedgehogs, and the British introduced “squid” mortars, which fired depth charges that were thrown ahead of the ship. And more escort vessels became available.

Admiral Dönitz, meanwhile, was reaching the conclusion that there were to be no more “happy times” for his fearsome fleet. Sinkings of U-boats mounted, and 40 were destroyed in the first quarter of 1943. Dönitz now also had to contend with an equally ruthless foe, a fellow submarine veteran and underwater warfare pioneer who would emerge as one of the crucial figures in the Allied victory in the Atlantic. He was 59-year-old Admiral Sir Max Kennedy Horton.

Max Horton: A Charming “Pirate”

On November 17, 1942, Horton had succeeded Admiral Sir Percy Noble as commander in chief of the critical Western Approaches Command, responsible for the day-to-day conduct of the battle against U-boats in the Atlantic. During his 20 months at the helm of the Western Approaches before being appointed head of the British Naval Mission in Washington, Noble had done much to improve antisubmarine measures and kept up the morale of escort and aircraft crews with a close, personal touch. He was a charming and charismatic officer—but lacking in aggressive drive.

The complex Horton was a sharp contrast to his predecessor. While Noble was a quiet-spoken naval gentleman, the rough-hewn Horton regularly challenged authority and refused to suffer fools gladly. A stern taskmaster who had gained a reputation in the Navy as a bully and a “pirate,” he was to prove well chosen for the post. He drove his new command hard from the start, fraying the nerves of subordinates and making his firm grip felt by every ship’s company. Admiral Sir Peter Gretton, a distinguished escort group commander, observed that Horton was “ruthless in weeding out the weak and replacing them by high-caliber officers.”

His chief of staff called Horton “a very great man possessing a dual personality, having on the one hand charm and kindness of heart not always realized, and on the other hand hardness which could at times be terrifying even to the toughest of men.” Another officer reported that Horton “had more personal charm than any man I have ever met, but he could be unbelievably cruel to those who fell by the wayside.”

A Royal Navy Submariner in WWI

Born in 1883 into a military family and the son of a wealthy stockbroker, Max Horton entered the Royal Naval College in Dartmouth, Devon, as an officer cadet on September 15, 1898. At the HMS Britannia training school there, he became a cadet captain, outstanding sportsman, and middleweight boxing champion. But he had a wild streak, chafing at authority, being insubordinate, and causing trouble in the mess. His commanding officer’s report in October 1907 cited Horton’s intelligence and “excellent” leadership qualities but noted that he used bad language and was a “desperate” motorcycle rider.

Horton chose the newly formed submarine service as a career because it was the least stuffy and hidebound branch of the Navy. It offered command at a young age and some freedom from authority and ceremonial ritual. Working closely and relying on each other’s technical and professional competence, officers and men enjoyed a special relationship. A submarine commander at sea or under it was independent, and the lone wolf aspect appealed to Horton.

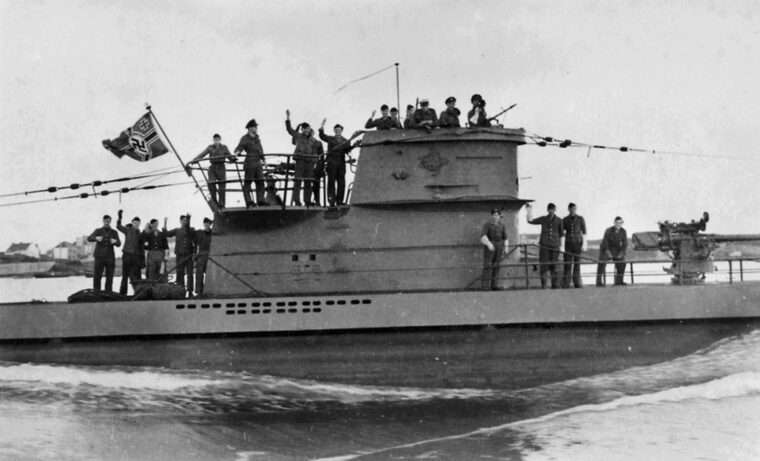

By the outbreak of World War I early in August 1914, Horton was already a lieutenant commander and in charge of one of the first few British ocean-going submarines, the 800-ton HMS E-9. He and a handful of other skippers soon distinguished themselves in action despite the fact that the diesel-powered British submarines, unlike U-boats, were plagued by constant mechanical troubles and a shortage of spare parts. On September 13, the E-9 penetrated the Heligoland Bight and sank the aging German light cruiser Hela with two torpedoes from a range of about 600 yards. A few days later, the E-9 sank the German destroyer S-116 in enemy waters. On returning to his base at Harwich, Horton flew the skull-and-crossbones pirate flag, establishing a tradition in the Royal Navy’s submarine service.

While patrolling off the Ems River in northwestern Germany on October 6, 1914, the E-9 torpedoed and sank the enemy destroyer S-126. Horton was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and recommended for early promotion. In December 1914, the E-9 and two other British submarines were deployed to the frigid Baltic Sea, where they wreaked havoc on German shipping. Horton sank a number of vessels there, including a destroyer, four merchantmen, and a collier, and seriously damaged the cruiser Prinz Adalbert. Because of his bold actions, the enemy called the area “Horton’s Sea” and put a price on his head.

Horton operated in the North Sea from January 1916 onward and emerged from World War I as the British submarine commander most feared by the Germans. He was given command of the Baltic Submarine Flotilla early in 1919. A Russian request for him to be appointed the senior naval officer in the Baltic was opposed by the Second Sea Lord, who said, “I understand Commander Horton is something of a pirate and not at all fitted for the position of SNO in the Baltic.” But the audacious submariner was awarded a bar to his DSO and promoted to captain in June 1920 at the age of 37.

After commanding the light cruiser HMS Conquest and the 29,150-ton battleship Resolution during the 1920s, Horton was promoted to rear admiral in October 1932. He flew his flag aboard the 30,600-ton Queen Elizabeth-class battleship Malaya for three years and then led the First Cruiser Squadron, flying his flag aboard the 9,830-ton HMS London. Given the rank of vice admiral in 1937, he then commanded the Reserve Fleet. He was credited with mobilizing the fleet by the time war came.

At the outbreak of World War II, Admiral Horton was placed in command of the Royal Navy’s Northern Patrol, which enforced the distant maritime blockade of Germany in the waters between Orkney, Shetland, and the Faeroes. When the Admiralty decided to revitalize the submarine service, Horton was called to take charge in January 1940. Drawing on his World War I experiences, he displayed strategic intuition, achieved a close relationship with Coastal Command, and was a tireless leader. Horton reached four-star admiral status in January 1941.

“The Right Man to Pit Against Dönitz”

Horton’s appointment to lead Western Approaches was a well-timed and inspired stroke, and he brought new earnestness to the command. Admiral Noble had laid fine groundwork and made the command run smoothly, but his dynamic successor swiftly instituted improvements and was a more relentless match for Dönitz and his U-boat scourge.

Horton understood the workings of the minds of Dönitz and his commanders. Captain Stephen W. Roskill, the eminent gunnery expert and Royal Navy historian, said of Horton, “With his knowledge and insight, his ruthless determination and driving energy, he was without doubt the right man to pit against Dönitz.” The German admiral eventually dubbed him “my own personal adversary-in-chief.” Horton’s grasp of the essentials was immediate, and on his first day in office he picked up where Noble had left off.

Able to reap much of what his predecessor had laboriously sown, Horton took over at a critical time when the insecurity of the North Atlantic threatened the Allied war effort, particularly the planned liberation of northwestern Europe, and demanded the undivided attention of senior naval officers and officials in London and Washington.

The Convoy Support Groups: Horton’s Cavalry

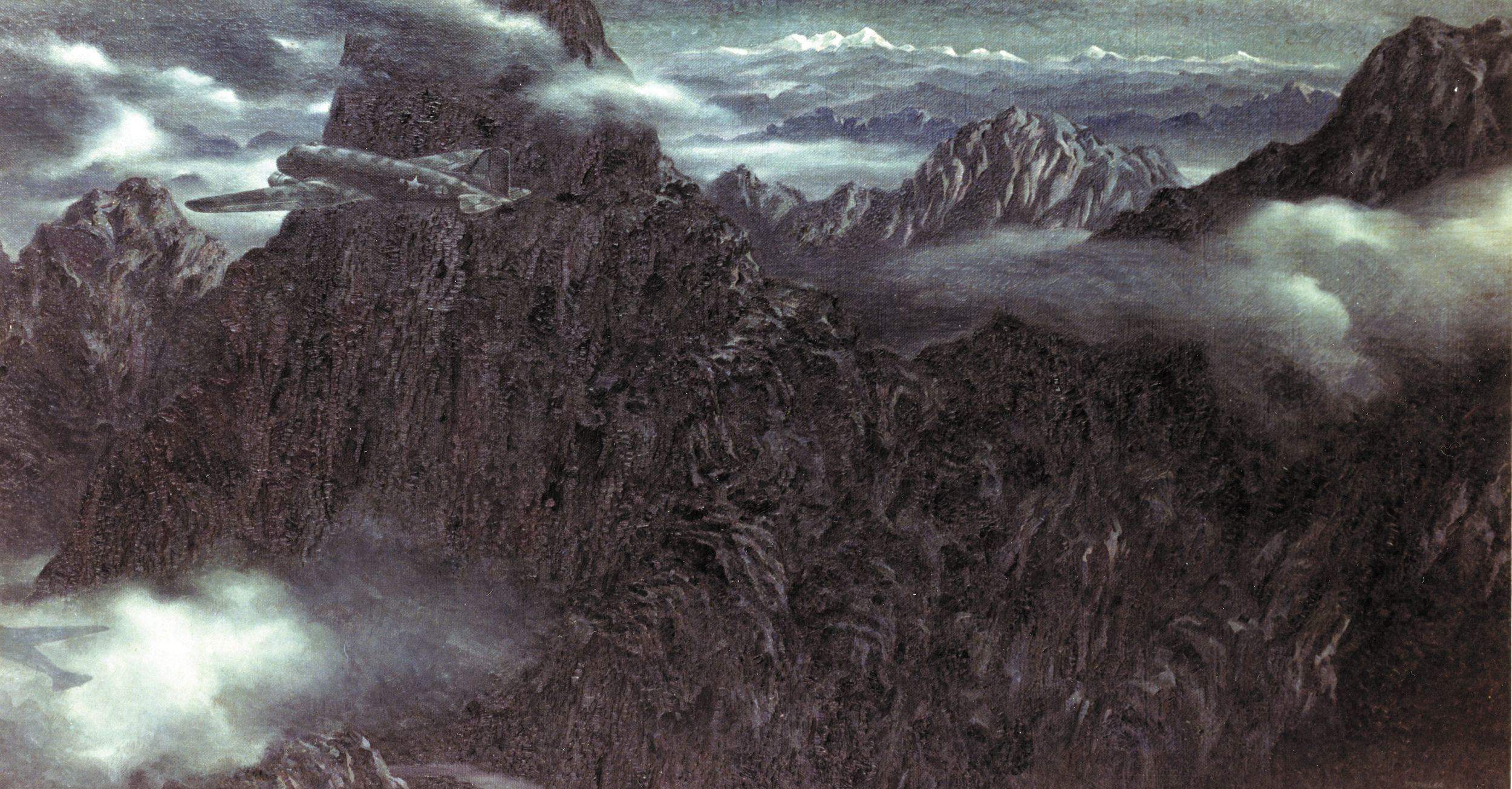

Swiftly and tirelessly, Horton strove to provide increased protection for the convoys carrying men, arms, and matériel from America and Canada to the British Isles. He demanded more long-range aircraft support, including B-24 Liberator bombers, Coastal Command Short Sunderland flying boats, and Royal Air Force Bomber Command Handley Page Halifax bombers. He rushed through advances in weaponry, such as rockets for carrier planes, and assigned special rescue trawlers to convoys, which eventually saved the lives of thousands of Allied seamen.

Most importantly, Horton ordered a series of changes in the operation of convoy escorts while sinkings by U-boats were still “the real danger.” He boldly reduced all convoy escort groups by one vessel to allow the creation of five support groups able to hit back at the U-boats in the mid-Atlantic. Horton reasoned that the U-boats, accustomed to being attacked from the direction of a convoy, would be thrown off balance when the support groups came in attacking from all quarters.

The groups each comprised six to eight destroyers, frigates, or corvettes, occasionally a British or American escort carrier, and MAC-ships, converted tankers and grain ships each carrying three or four Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers. Based in Newfoundland and Iceland, the support group vessels had no escort duties but were used to hunt U-boats and rush to the aid of convoys under attack. The support groups, said Churchill, were “to act like cavalry divisions…. This I had longed to see.”

“School of Battle”

Horton was a training fanatic, so he set about ensuring that sailors and seamen operating in the Western Approaches were fully able and motivated to cope with the rigors of antisubmarine warfare. An escort commander reported, “He drove and drove and drove at training, shore training at their bases, sea training, sea and air training all the time, even when with the convoys.” Horton established the North Atlantic Tactical Training School in Liverpool, where, according to Sir Robert Atkinson, his brilliant leadership turned out “a highly trained force.”

Horton also set up a “school of battle” at the Northern Ireland seaport of Larne in early February 1943. Centered around HMS Philante, a converted luxury yacht, and two submarines, the school’s aim was to “exercise escort vessels in the art of sinking U-boats.” The school, observed Admiral Gretton, was “a thoroughly practical affair and of great value.” Horton took a keen interest in the school’s progress and went to sea in the Philante for important tactical experiments.

Attack on ONS-5

Horton displayed remarkable strategic sense in the disposition of his forces, and his support groups made persistent and successful counterattacks against Dönitz’s wolf packs. The tide began to turn in the bitter battle of the Atlantic. In April 1943, Dönitz’s crews sank 328,000 tons of shipping, half the preceding month’s total, and 14 U-boats were destroyed, seven by escorts and seven by aircraft. For each three merchant ships lost, a German submarine was destroyed. Admiral Horton sent a message to Western Approaches naval and air units in which he observed, “The tide of the battle has been checked; the enemy is showing signs of strain.”

The showdown commenced on April 28, when a slow-moving, westbound convoy codenamed ONS-5 was ambushed in the North Atlantic by several wolf packs. Escorted by a destroyer, a frigate, and four corvettes, the 42 merchantmen were zigzagging through storms and fog when 51 U-boats closed in. Some of the escorts had to withdraw for refueling, but two escort-hunter groups sped to the aid of the convoy. At intervals when the foul weather permitted, Allied planes flew in to strafe the U-boats or force them down. When the battle ended on May 6, a dozen Allied ships had been sunk, but also seven enemy submarines. The attack on ONS-5 was the biggest of the Atlantic war, with the heaviest losses.

Turning the Tide in the Battle of the Atlantic

Four other convoys against which Dönitz dispatched wolf packs that climactic month completed their crossings unscathed, although six U-boats were sunk in vain attacks. During the next three weeks, 12 Allied convoys traversed the Black Pit with the loss of only five vessels, while the escort groups and patrol bombers sank 13 of Admiral Dönitz’s U-boats. A number of others were severely damaged. Losses of 30 percent that May represented a rate that his U-boat command could no longer tolerate, and even the high morale of his well-trained, seasoned crews was seriously shaken.

The German losses were brought sharply home for Dönitz when he learned that his 20-year-old younger son, Sub-Lieutenant Peter Dönitz, and all his comrades had perished in the sinking of U-954. Adding to the admiral’s woes, meanwhile, was the fact that more of his boats were being sunk by B-24s, Sunderlands, and Vickers Wellingtons of RAF Coastal Command along the western coast of France and in the Bay of Biscay. By that time, life at sea for the U-boat sailors was almost unbearably arduous and perilous.

Dönitz reported to Hitler, “We are facing the greatest crisis in submarine warfare, since the enemy, by means of new location devices, makes fighting impossible and is causing us heavy losses.” Dönitz said later, “In the submarine war, there had been plenty of setbacks and crises … but we had always overcome them because the fighting efficiency of the U-boat arm had remained steady. Now, however, the situation had changed. Radar, and particularly radar location by aircraft, had to all practical purposes robbed the U-boats of their power to fight on the surface. Wolf-pack operations against convoys in the North Atlantic … were no longer possible.”

Concluding reluctantly, “We had lost the Battle of the Atlantic,” Dönitz ordered his submarines on May 24 to withdraw from the North Atlantic to an area southwest of the Azores. Admiral Horton was able to triumphantly signal his escorts, “In the last two months, the Battle of the Atlantic has undergone a decisive change in our favor. All escort groups, support groups, escort carriers and their machines, as well as the aircraft from the various air commands, have contributed to this great success. The climax of the battle has been surmounted.”

The End of U-Boat Operations in the Atlantic

After June 1943, the U-boats never again posed a threat to Britain’s lifeline, upon which depended the massive Allied invasion of Normandy a year later. New destroyers and other purpose-built escort vessels entered service in increasing numbers, and merchant shipping construction was finally outstripping losses. Although U-boats were still being built at a rate that kept pace with sinkings, the new crews lacked the training and experience of their predecessors.

Dönitz would not yield and renewed his offensive in September-October 1943. But he was fighting a losing battle. Out of 2,468 Allied merchant ships that sailed in 64 North Atlantic convoys during that period, only nine were lost. Twenty-five U-boats were destroyed. This caused Dönitz to stop deploying his boats in large groups.

When Britain made an agreement with Portugal and took over two air bases in the Azores early in October, Allied planes were able to cover the whole North Atlantic, and worse losses befell the U-boat fleet. In the first three months of 1944, only three merchantmen were sunk out of the 3,360 that crossed in 105 convoys, and 36 U-boats were sent to the bottom. Dönitz cancelled all further operations against convoys and told Hitler that there could be no renewal without new types of U-boats, better defensive equipment, and air reconnaissance.

“He Loved Power, and Used it Mercilessly”

After almost five years of severe hardships and terrible losses in lives, ships, and matériel, the Allies won the crucial Battle of the Atlantic. Without that victory, Operation Overlord could not have been mounted on June 6, 1944. A few U-boats remained in action, nevertheless, until the end of the European war. On May 7, 1945, the day on which the unconditional German surrender was signed, two merchant ships were sunk off the Firth of Forth in Scotland by U-2336.

No man did as much to ensure Allied victory in the unforgiving Atlantic as Admiral Max Horton. Shrewd, intelligent, and energetic, he made sound decisions that swiftly bore fruit at the most critical time of the war. He refused to tolerate inefficiency and did not shrink from opposing Churchill or the RAF while fighting for scarce resources. His abrasive personality won him few friends in the press or among senior officers in the Royal Navy, but his zeal and dedication brought wide respect.

Fleet Admiral Sir Andrew B. “ABC” Cunningham, the famed commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, First Sea Lord, and naval adviser to Churchill, said of him, “Horton I have a great admiration for, although I do not think his judgment is always sound. His main fault, in my opinion, is that he sets everyone by their ears and is inclined to bully his immediate juniors. He is, however, full of energy…. He loved power, and used it mercilessly, taking upon himself the mantle of the strong man apart. He was not of the type who could reprimand an officer on the quarterdeck and afterwards enjoy a glass of gin with him in the wardroom…. He framed his policy on the survival of the fittest, and was sparing with his praise.”

Besides the DSO and bar, Admiral Horton was awarded the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath for his outstanding service. At his own request, he was placed on the retired list in August 1945 so as to facilitate the promotion of younger officers. He traveled in France and other parts of Europe after the war and died at the age of 67 on July 30, 1951.

Please add to your otherwise splendid account of Admiral Max Horton, that he was born in Anglesey to Robert Horton and Esther Goldsmid, of the famous anglo-Jewish family, and was halachically Jewish through descent from his mother’s line

Martin Sugarman (AJEX Jewish Military Museum and Archivist)

My farther served in the Royal Navy 1931 to 1954 he was commended for action against the enemy by Admiral Sir Max Horton. Dad was then serving on the HMS Pelican she was a Egret Class Sloop under the command of (Capt.G.N.Brewer R.N.) the Pelican was credited with HMS Jed the destruction of 4 German U-boats dates…11-7-1942..U-136 NW of Madeira…6-5-1943 U-438 NE of Newfoundland…14-6-1943 U-334…West of Butt of Lewis…14-4-1944 U-448 North of the Azores. I was in touch with the Ministry of Defence and received the Arctic Star for my fathers service on the Russian convoys to Murmansk and Archangel. The commendation dose not say other than that above what he did, Dad left the Royal Navy as a P.O.S.M.

One of my Uncles was on board H.M.S. Isis during World War two. A destroyer . A Able body Sailor .