by Donald Roberts II

British colonization of the New World transplanted many British institutions to America. Besides the political and social beliefs seeded in the colonies, military ideals were also implemented. Whereas European warfare was coming to depend increasingly on professional armies, the same cannot be said about the military in America.

[text_ad]

From the start in the colonies, the military focus was based on the British citizen-soldier concept. That is, for the defense of the colonies, there would be a militia force of citizens who would train for war whenever possible. Without the funds or manpower to provide an entire class of professional soldiers to defend themselves, the early settlements at Jamestown, Plymouth, and each successive settlement that followed had to rely on militia for protection.

“Common” and “Volunteer”

Eventually, legislative policies made service in militia units mandatory, with regular training schedules established. As the population increased along the East Coast, company-sized units were formed when sufficient numbers of men were acquired in each settlement and surrounding areas. Where the population was larger, regiments were organized from the various companies.

Over time, there evolved two basic types of militia units. One, “common militia,” was based on the idea of compulsory service. Units regarded as common militia were seldom called up for emergency service.

The second type of unit, “volunteer militia,” was composed of men who chose to be the first to be called up in an emergency. Since the understanding was that volunteer units would be called to active duty first, an elite status was often associated with the volunteers. When reinforcements were needed in volunteer units, they were usually drawn from the ranks of the common militia units.

Rogers’ Rangers and Indian-style Combat

Well into the 18th century, many militia groups from the eastern communities and towns began to study and adopt European-style training procedures and tactical doctrines. With their emphasis on tight infantry formations maneuvering on large, treeless plains and massed concentrations of volley fire, the European tactical concept led many colonial militia units to lose their ability to fight Indian-style in the wilderness. That is, accuracy with the musket and personal concealment were not considered so important to many non-frontier militia units.

These factors became evident by the time of the French and Indian War. They were so apparent that Colonel George Washington of the Virginia militia wrote, “Without Indians [on our side], we shall never be able to cope with those cruel foes to our country. Indians are the only match for Indians; and without these we shall ever fight upon unequal Terms.”An exception during that war was Rogers’ Rangers. This unit consisted mainly of frontiersmen who often found themselves conducting many Indian-style long-range offensive operations.

“No Dependence” in the American Revolution

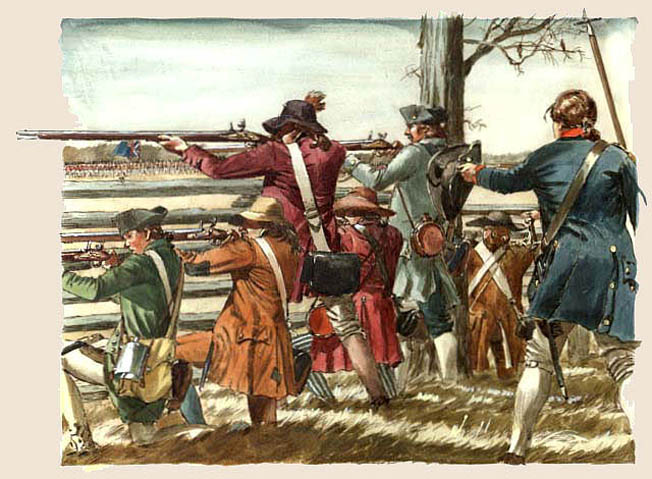

For the most part, when the American Revolution began, militia units were no longer training in the methods necessary to defeat groups of hostile Indians, the very types of enemy formations they had been created to fight against in the first place. Thus, when hostilities broke out with Britain, the colonial militia was unprepared for both frontier-style fighting and, owing to their nature as part-time soldiers, for facing British regulars in open-field battles.

However, the early battles of the war verified what had become a solid characteristic about militia: When fighting defensively, militia could be very effective in battle. Conducting offensive operations was another matter. When militia were used in extended offensive campaigns that took them away from their home region or state, they became less effective. Their appearance and disappearance from camp at any time and general disregard for military order and discipline led General Washington to maintain his initial opinion of militia that “no Dependence can be put on the Militia for a Continuance in Camp, or Regularity and Discipline during the short Time they may stay.”

Successful Guerrilla Campaigns

One of Washington’s true strengths as a general was learning how to get the most out of his citizen-soldiers. He used the militia to supplement the size of the Continental Army during many periods of the war, which was critical for success in the war that Washington was waging.

Aside from supplementing the ranks of the Continental Army (inconsistently), militia forces were able to obtain a relatively high level of success. The key to this achievement was good leadership. Usually, when militia units were commanded by strong, competent leaders, the citizen-soldiers performed well in battle, as was the case in the Battles of Bunker and Breed’s Hills, Guilford Courthouse, and Cowpens. At the same time, militiamen executed some successful guerrilla campaigns under the leadership of such fine officers as Francis Marion, William Davidson, William Davie, and Daniel Morgan.

The Last Years of the War

During the last years of the war, Continental officers (Washington included) learned to appreciate the strengths and weaknesses of militia. In doing so, Continental regiments were often dispatched to help local militia defend their home region. At the same time, in situations where British forces would suddenly attack, Washington and other Continental officers would position militia to counter these thrusts, thus allowing them time to maneuver regular regiments of the line into better positions for engaging the enemy.

Although there were shortcomings with militia during the war, there were just as many positive characteristics associated with them. Without the effective use of and performance by the militia in a conflict that lasted eight years, it is doubtful that the American war effort could have sustained itself long enough to be victorious.

Originally Published April 27, 2014

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments