by Vince Hawkins

Usually considered to be a single maneuver, Frederick the Great’s “oblique attack” or “oblique order” was in fact two distinct grand tactical maneuvers, each of which could be executed separately or in combination as demonstrated at Leuthen. When the two maneuvers—the “march by lines” and the “attack in echelon” were performed together to create the “oblique order.”

The purpose of the oblique order was to bring together a superior concentration or overwhelming force against a specific sector of the enemy’s position, usually the flank. Although attacking an enemy’s flank is as old a tactic as warfare itself, Frederick developed two new and distinctive means of doing so. Before Frederick, armies would engage in a flank attack using only a part of their field force. Frederick’s concept was to use his entire force, essentially shifting his entire “axis of attack” to a different position from which it started.

“Oblique Order” Step 1: “March By Lines”

Such a maneuver had been attempted by other commanders in the past, but almost always their movements were, by necessity, hidden from the enemy, utilizing covering terrain, night, or poor visibility. To shift the front of one’s army during battle, particularly in the 18th century, took a great deal of time. While the shift was in progress, the enemy could either move his own front to face the threat, thereby negating the maneuver, or attack the maneuvering army, catching it while it was facing the wrong direction and particularly vulnerable.

Such a maneuver had been attempted by other commanders in the past, but almost always their movements were, by necessity, hidden from the enemy, utilizing covering terrain, night, or poor visibility. To shift the front of one’s army during battle, particularly in the 18th century, took a great deal of time. While the shift was in progress, the enemy could either move his own front to face the threat, thereby negating the maneuver, or attack the maneuvering army, catching it while it was facing the wrong direction and particularly vulnerable.

Frederick overcame these problems with the “march by lines.” Upon reaching the battle area the Prussian army would deploy in its standard two lines of battle paralleling the enemy’s position. They would then simply quarter wheel by sections or divisions, to the left or right, and reform into columns. Because every unit was doing this at the same time, the entire army could be reformed into columns in as little as two minutes.

The columns would then march off, angling, or “obliquing,” slightly to bring them closer to the chosen flank and the enemy. Because the columns were made up of the same units that had formed the battle lines, Frederick called the maneuver “marching by lines.” Once they reached their designated position the columns would quarter wheel again, this time in the opposite direction from their starting wheel, and they would instantly be reformed into their original two-line battle formation.

A Loss of Both Position and Morale

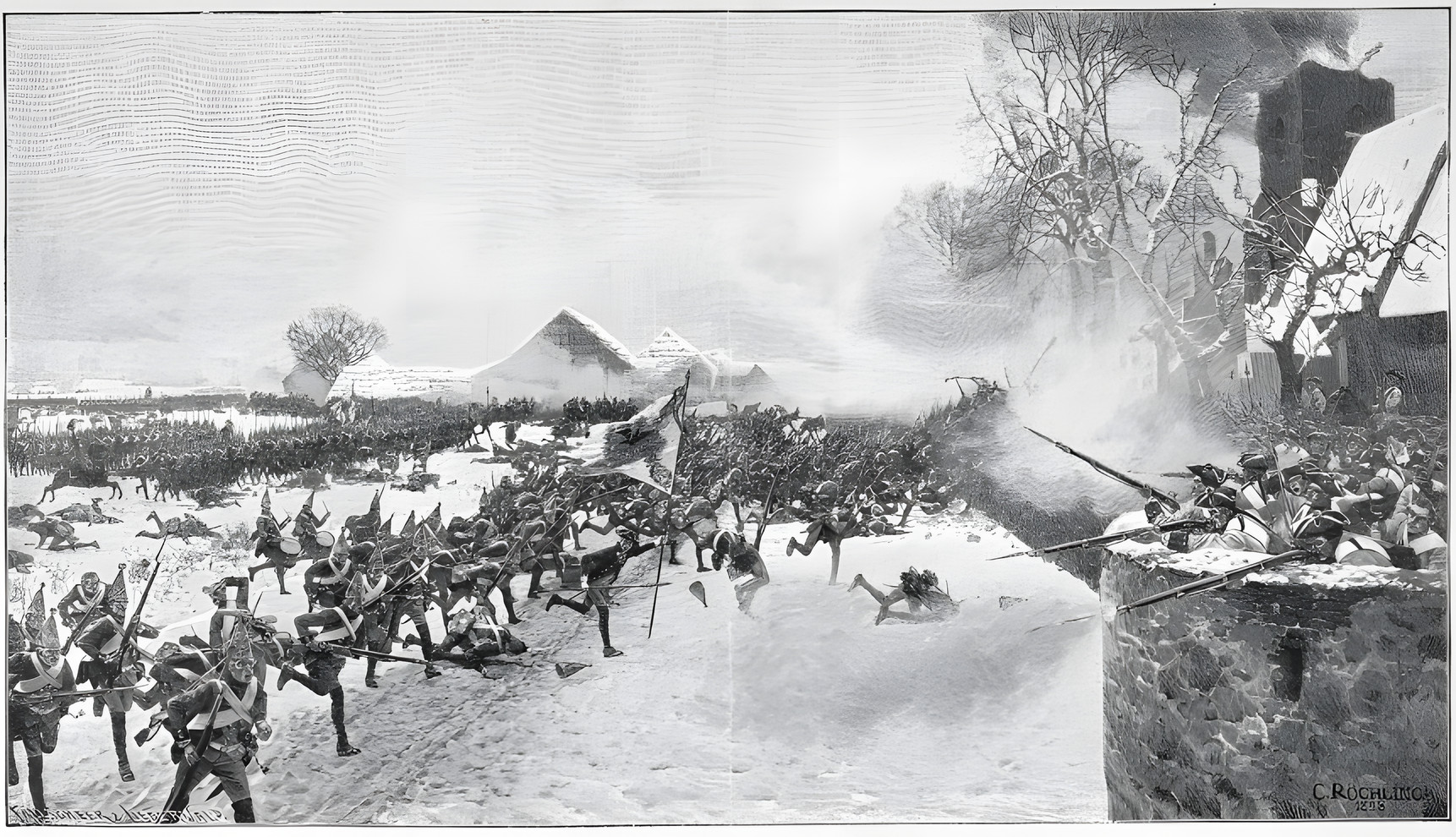

When the maneuver was completed, the army was deployed across the enemy’s flank at an angle or oblique of 30 to 45 degrees from its original line. The attack was then carried out by concentrating as much force as possible against the enemy flank.

Usually, this initial force consisted of an advance guard supported by one or more lines of infantry, a flank guard of cavalry, and 30 to 40 pieces of artillery. When executed properly, the oblique order maneuver rarely failed to either roll up the enemy’s army from the flank, or cause him to try to turn his army to face the new threat, thereby placing his army at a disadvantage of position and morale. Often, just the appearance of the Prussian army on its flanks was enough to send an enemy in a panicked retreat from the field.

“Refusing” The Battle Lines

In some cases, most notably that of Leuthen, the battle line could be “refused,” or angled away, by unit increments from the enemy’s line. This meant that if the Prussian army tried to oblique across the left flank of the enemy line, the advance guard and attack force would be at the right or top of the line and the units to its left would be in echelon or staggered back, each unit in the line being deployed slightly behind the unit to its right and slightly in front of the unit to its left. This would “refuse” the left of the line.

Refusing the line had two advantages: first, it protected that part of the line not yet engaged while at the same time holding the opposing part of the enemy’s line in place, waiting for an attack; and, second, it confused the enemy as to the Prussians’ intentions because looking at the Prussian formations from a distance the enemy was unable to tell which formation was being employed. The entire Prussian army gave the appearance of advancing fragmented and in disorder.

Simple Concepts, Very Difficult Execution

Although these maneuvers might seem to be relatively simple and easy to imitate, quite the opposite is true. At Prague and Kolin Frederick attempted to use the oblique order and failed to do so properly. At Leuthen, he personally oversaw every step of the maneuver to ensure its success.

Although these maneuvers might seem to be relatively simple and easy to imitate, quite the opposite is true. At Prague and Kolin Frederick attempted to use the oblique order and failed to do so properly. At Leuthen, he personally oversaw every step of the maneuver to ensure its success.

To employ the oblique order successfully demanded two prerequisites. The first was a well-trained, highly experienced officer corps. Each officer had to be expert in his duties, know exactly when to do what at a given signal, and have complete control over his men in any given situation. The second was a well-trained, highly motivated army.

The men had to be as experienced as their officers, know their drill perfectly, and be able to execute the orders given them under the most severe battle conditions. In essence, a professional army was required, and Prussia had the first and only professional army in Europe since Roman times. Frederick had seen to the training and education of his officers and their dedication to king and country.

Frederick’s Hands-On Approach to Command

Frederick had also seen to the training of his soldiers, particularly their marching ability. The Prussian army had become experienced in the cadence-step style of marching under Frederick’s father, then with Frederick they attained a level of proficiency and expertise unequaled by any other army in Europe at that time. They were thus able to march faster and farther, while still retaining their formations, than any of their enemies.

At Leuthen, Frederick the Great took full advantage of the ground to screen his army’s movements, but he also counted on the ability of his men to march around the enemy’s flank and execute the oblique order before the enemy could react. When executed properly, the oblique order was a winning tactic a defender could do little to counter.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments