By Don Haines

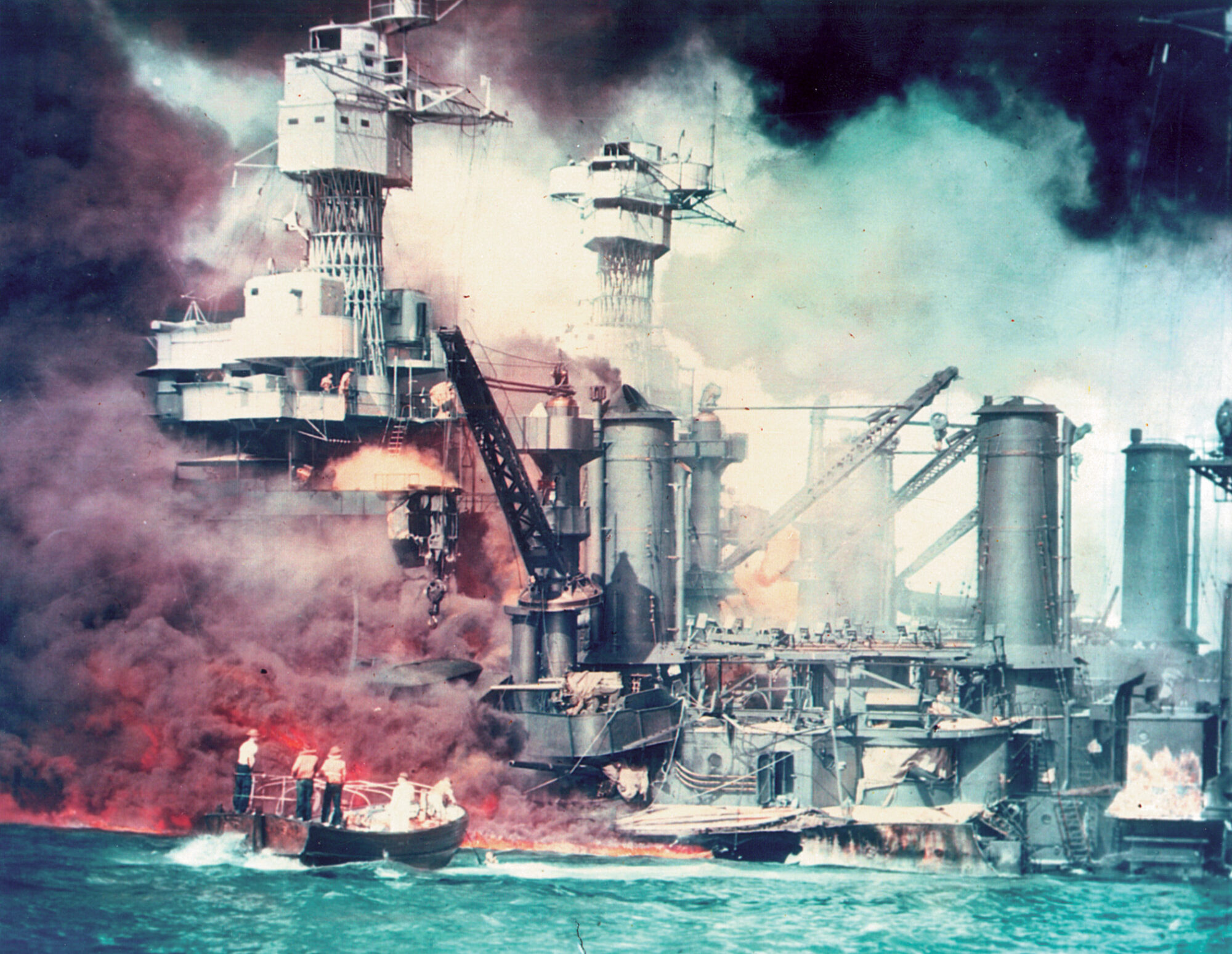

When Nathan and Jane Olds of Stanton, ND; Ralph and Vera Endicott of Aberdeen, Wash.; and Effie Costin of Henryville, Ind., were informed by the U.S. Navy in December 1941 that each of their families had lost a son during the Japanese earl Harbor bombing, they were heartbroken. Clifford Olds, 20; Ronald Endicott, 18; and Louis “Buddy” Costin, 21, had been sailors on the battleship USS West Virginia, which had been hit by a series of bombs and torpedoes. The telegrams merely stated that the three young men “died at their duty stations.” But during the ensuing years another story began to emerge—one so horrible that family members who learned the truth decided not to tell the parents in order to prevent them from suffering further.

Terse Telegrams Didn’t Tell The Full Story

Harland Costin, younger brother of Buddy, found out in 1942 when a chance meeting with a crew member of the now refloated West Virginia told a sad tale that by now has become legend. It was a story of three young men who had survived for what must have been 16 hellish days in the dark pump room of a battleship sitting on the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Costin, Olds, and Endicott had not died easily or willingly, as attested to by witnesses who remember. (Hear about more eyewitness accounts from the Day of Infamy and other critical moments in the war inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

Desperate Banging on the USS West Virginia

“It was worse at night,” said Marine Corps bugler Dick Fiske. “You’d hear bang-bang-bang, then stop, then bang-bang-bang from deep in the bow of the ship. It didn’t take long to realize that men were making that noise.” To this day Fiske chokes up when he tells the story. “Pretty soon nobody wanted to do guard duty, especially at night when it was quiet. It didn’t stop until Christmas Eve.”

Bob Kronberger, who was a crewman on the USS West Virginia, says he knew all three of the young sailors. “I didn’t know them well because I was of a higher rank and couldn’t fraternize, but it was an awful way to die.” Kronberger is a good example of the fortunes of war. His brother and father were also part of the West Virginia crew. All three survived the attack.

A Family Legacy Of Tragedy

It was not hard for Harland Costin to make the decision not to tell his family about the true circumstances of Buddy’s death. His family had already suffered much. A brother had died young of an infectious disease. The father had died in a fight. To tell his mother how Buddy must have suffered might have been too much for her to bear. He would keep his secret until the 1990s, when newspapers began to report the story.

Duke Olds found out about his brother’s struggle to live from a relative who worked at the shipyard in Bremerton, Wash., where the USS West Virginia had been taken for repairs. Olds told his brother and two sisters but not his parents. “It would have been really hard on my father. He and Cliff were real close. It was best to let it be.” It would be many years before Duke would find out that what he thought had been a well-kept secret had been revealed to his mother not long before she died. “They say she took it really hard.”

One Last Night Out Before Infamy

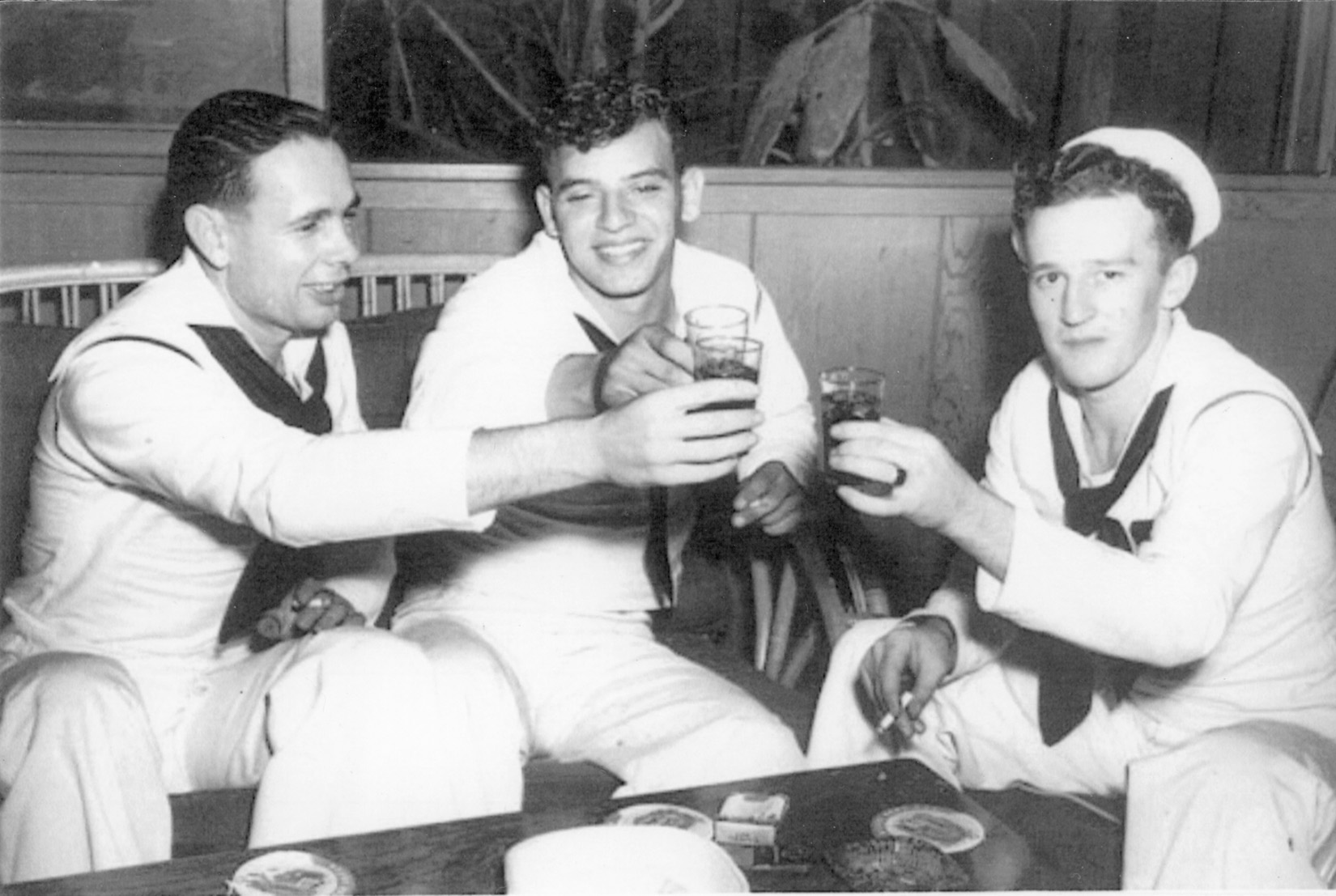

Jack Miller, a buddy of Clifford Olds, says he knew his friend was one of those making the noise that was coming from the bow section. Clifford had often invited him into the pump room for conversation. Just for laughs, they would close the hatch and scream all manner of epithets in the airtight space, knowing no one on the outside could hear them. The night before the attack, Cliff, he, and another buddy had gone to a Honolulu nightspot together. They had said no thanks to a barmaid who had taken their picture and offered to sell it to them. Miller could not know that the morrow would change their lives forever—and how much that photo would come to mean.

Ronald Endicott had joined the Naval Reserve at age 17, mainly because he wanted to emulate his father who had served earlier. He had been on active duty for 10 months when the Japanese rained death on his ship and he found himself entombed in Pump Room A-109 with Olds and Costin. Velma Lawrence, now of California, was Endicott’s childhood sweetheart and says his parents left Aberdeen in 1956. She knows they never knew how their son died.

Fateful Decision Saved And Doomed

No doubt the main reason for the state of anguish among the sailors topside stemmed from the fact that they knew rescue was impossible. Olds, Costin, and Endicott were sitting on the bottom of Pearl Harbor, surrounded by water. The ship’s commander, Captain Mervyn S. Bennion, had been killed in the early moments of the attack, but quick thinking by a young lieutenant who was also the fire-control officer ensured the West Virginia would sink on an even keel.

It is somewhat ironic that the three men were doomed; the young officer’s action saved hundreds but ensured their deaths. Had the WeeVee, as the ship was affectionately known, capsized like the battleship USS Oklahoma, the three might have been rescued by cutting through the hull. Not that rescue would have been guaranteed, as the Oklahoma rescuers discovered. Many men on that ship died of asphyxiation when air rushed out as soon as the hull was breached.

Those topside on the WeeVee also knew that rescue from below the waterline by drilling a hole through the hull would result in a blowout, killing the diver. Added to this was the realization that the United States had been plunged into war, and many things had taken precedence over three enlisted men at the bottom of Pearl. Those above knew it was not a question of whether Olds, Costin, and Endicott could be rescued. It was only a question of how long they would last.

“Does Anybody Up There Hear Us?”

The three entombed young men, who had only three years of service between them, probably did not know they were doomed. They wanted to live, and they had more on their side than their comrades knew. They had emergency food rations, access to the fresh water compartment, flashlights to enable them to see, and two other things—an eight-day clock and a calendar. And so they banged. At the end of each 24-hour period, they marked their calendar. No doubt they wondered, “Does anybody up there hear us?”

They were heard, but nothing could be done. The brass probably saw them as they did all the dead men below. They could not be helped, so efforts were concentrated on the living.

Despite all the remembrances, the story of the three trapped sailors might never have been released to the public without the salvage report filed by Commander Paul Dice during body-retrieval efforts in May 1942.

While many of the 106 deaths on the USS West Virginia were from drowning when compartment hatches had to be closed on those trying to escape, Dice immediately noticed that Pump Room A-109 was completely dry. Three bodies were found huddled together on the storeroom shelf. Then Dice saw flashlights and batteries strewn about, along with empty food ration cartons. The manhole cover to the fresh water tanks had been removed. Then salvage workers saw the eight-day clock and the calendar with a red X marked through each day through December 23. With this discovery, grown men broke down in tears.

Dice’s official report is matter of fact and devoid of emotion. “Three bodies were found on the shelf of storeroom A-111, clad in blues and jerseys. This storeroom was open to fresh water pump room A-109, which was apparently the battle station assigned to these men. The emergency rations at this station had been consumed and the manhole cover to the fresh water tanks had been removed. A calendar which was found in the compartment had an ‘X’ marked through each day from December 7, 1941, through December 23rd, inclusive.”

Dice kept the eight-day clock until, as an old man, he donated it to a museum in Parkersburg, WV, his hometown. He sent the calendar to naval headquarters in Washington. It has never been found.

Unfair Death Date On Tombstones

The three sailors were buried in a mass grave with 22 others. That is what officials told Harland Costin when he journeyed to Honolulu in 1945. In 1949, when the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific was opened, the bodies were disinterred and given separate burials. Clifford Olds’ remains were shipped home to Stanton, ND. Costin and Endicott are buried in the National Memorial Cemetery in Honolulu, which is commonly referred to as the “Punch Bowl.” The three stones are identical and have death dates of December 7, 1941. There is unanimous agreement that the death date is unfair in view of the heroic struggle waged by the three young sailors to stay alive.

When Jack Miller (who died in 2002) returned to Honolulu after sea duty, he understood that the photo taken by the barmaid was one of the last snapped before the world fell apart. He retrieved the negative and kept it for the rest of his life. It shows three carefree young men out on the town and was the last happiness Clifford Olds would ever know.

Submerged Wristwatch Restored By Sailor’s Mother

Hundreds of thousands of young men died in World War II. They all had names and faces. They all had a story and people who loved them. When Buddy Costin’s locker was cleaned out after the raising of the WeeVee, a water-soaked ladies’ wristwatch was found. It was intended as a Christmas present for his mother. She had it restored and wore it until her death in 1985.

Harland Costin and his sister, Edna, still live in Southern Indiana, and the memories of their older brother are ever fresh. “Buddy was such a cut-up, always making jokes and getting into mischief. One of his favorite things was grabbing Mom and waltzing around the kitchen. When he came home on his first leave, he went to school and apologized to all the teachers for raising such havoc in their classes. They loved him,” Edna recalled.

Edna says she cried a lot the day she got a call from the Honolulu Advertiser telling her the story of her brother’s struggle to survive. “We assumed he’d been killed instantly and therefore didn’t suffer.” Now she can’t help but think of her older brother below in his ship trying desperately to let those above know he was still alive.

Honolulu Fitting Resting Place

Letting Buddy’s gravesite remain in Honolulu was not a difficult decision. “It was where he wanted to be.” The Costin family has made several pilgrimages to section Q1105 of the National Memorial Cemetery. They hope someday his date of death will be changed, and they cannot help but think that if Buddy had found a way to make it out of the pump room, he might be alive today, a spry 82-year-old who would still be waltzing.

Dwaine “Duke” Olds will never forget the brother who was nine years his senior. “Cliff loved motorcycles. We still have a picture of him sitting on his bike, dressed in leather. He was a feisty little guy, always picking fights, though he usually lost. Cliff was very close to our Dad. Wherever Dad went, Cliff was right on his heels. Actually, Cliff was in the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) before he joined the Navy. He was making $19 a month in the CCC and he got a $2 raise when he joined the Navy. That was a lot of money back then. And you know, out of that $21 he sent $18 home—said he didn’t need it. Mom put it in bonds.”

No doubt, Clifford Olds’ story mirrored that of other young men who joined the military before World War II. They were children of the Great Depression. In many cases, serving as a lowly enlisted man in the military was superior to any civilian job they could get.

Memories Of Teenage Sweetheart Remain Strong

Velma Partridge (now Lawrence) was only 14 when she became the steady girlfriend of 17-year-old Ronald Endicott. Until now she did not know that the tall, blond, blue-eyed young man who was her first love was one of those trapped in the pump room. “I’d heard the story of the trapped men because it was published in the local paper in 1991. As a matter of fact, his parents got word the middle of December in ¸41 that he’d been killed. It tears your heart out to think that at that very moment, he was trying desperately to live.”

Velma says she remembers that her long-ago sweetheart always wore a leather jacket. “To this day, anytime I smell leather I think of him. It’s funny, because he was tall and thin, but everyone called him ‘Tubby.’ It was a nickname that went back to the time when he was a baby.”

Velma Lawrence went on to marry and have four children and many grandchildren. “I’ve had a wonderful life, but Tubby will always have part of my heart.” Lawrence says that on their last night together they went to a Charlie Chaplin movie. “The next night my Dad and me took him to the bus, and I never saw him again.”

The Men of the USS West Virginia Maintained Navy Discipline to their Final Moments

World War II Navy lore is full of courageous yet sad stories that have been fully told. Yet the story of three young sailors and their heroic struggle to stay alive on the bottom of Pearl Harbor lives only in a few belated newspaper columns and the memories of some shipmates, most of whom have now passed away.

It is time to recognize them. They kept their discipline and a record as they tried mightily to live. They may have died not knowing what catastrophe had befallen them. Had they lived, no doubt they would have gone to war against the Japanese enemy with the same determination as their shipmates.

Louis “Buddy” Costin, Clifford Olds, and Ronald “Tubby” Endicott deserve more than a Purple Heart and an incorrect date on their tombstones.

To the families of the three soldiers,

I’m deeply moved and so very sorry for such a tragedy.

I have the utmost respect for men of that generation for their passion for their country and love and respect of their families.

This country has lost the best men this world has ever offered.

Sincerely,

Crusty Gridley

Thank you Don Haines for writing this. Buddy Costin is my uncle. My Mom (his sister) did not know about this until the papers publilshed it. Thank you for helping him be remembered. John Moore

I just learned of this story today, the 80th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. My heart breaks for the brave young men and their families. I will remember this always and am so sorry this happened.

Pam

Around this time every year I think about Uncle Buddy. My grandma Barbara Costin/Moore was such a treasure, and loved her brother Buddy very much. My first born son is named Costin, for great Uncle Buddy and we will always remember the brave men who served our country on that infamous day.

My brother’s dad, Paul T. King, was on the USS West Virginia when it was attacked and sunk at Pearl Harbor. The next day he was transferred to the USS Benham, which was sunk by a single Japanese torpedo on November 15, 1942, during the Naval battle of Guadalcanal. He survived that sinking also.