by Glenn Barnett

On Sunday December 7, 1941, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt hosted a luncheon for 31 people at the White House. All present hoped her husband, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, would join them. At the last minute FDR demurred, choosing instead to eat privately with his friend and aide Harry Hopkins.

When her luncheon was over Mrs. Roosevelt retired upstairs to the family quarters, where she found a whirlwind of activity. It was then that she learned what her husband had only just found out: The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor.

In the months leading up to the war, Eleanor had been active with the Office of Civil Defense, and in this capacity she now swung into action. The following day she accompanied her husband to the capitol where he delivered his famous “Day of Infamy” speech asking Congress to declare war on Japan. That night she boarded a plane along with former New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, who worked with her on the OCD. Their destination was the West Coast, where they planned to inspect and discuss preparedness for civilian defense against an anticipated Japanese attack.

While in the air, a rumor reached them that San Francisco was under attack. All were relieved when the rumor was proven untrue. Eleanor’s tour of West Coast preparedness took a week, and on December 15 she was back in Washington. It was the first of many wartime trips that she would take on behalf of her husband and the government.

Even before the war, Eleanor Roosevelt was the most active of any First Lady, and certainly the most prolific activist. Her fight on behalf of civil rights, the poor, and women made her the lighting rod of the administration. During the war all of her activities, including her tours overseas, were scrutinized by enemies of the New Deal. During war it might be considered unpatriotic to attack the commander in chief so Eleanor was a highly visible scapegoat.

By the summer of 1942, representatives from most of the Allied governments had visited the White House, and many of them tendered invitations for Eleanor to visit their countries, including China and the Soviet Union. When the Queen of England discreetly inquired if Mrs. Roosevelt would be willing to visit Great Britain, Franklin got involved. He was keenly interested in having his wife visit the English ally.

When the official invitation came, it offered Eleanor the opportunity to see what the British women were doing for the war effort and to visit with recently arrived American soldiers. FDR encouraged her to accept. He did not tell her about the evolving plans for Operation Torch, the upcoming invasion of North Africa.

On October 21, Eleanor and her friend and aide Malvina Thompson (known as Tommy) boarded a Pan Am clipper on one of the first passenger flights to England since the war began. Foul weather forced the plane down in neutral Ireland, where they were met by the American ambassador David Gray, Eleanor’s uncle by marriage. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent a plane for them to complete their journey, and the travelers were soon at Buckingham Palace, where they were the guests of the King and Queen for two nights.

The First Lady was Shocked by the Extensive Damage Caused by the Blitz

The royal palace was a surreal place in wartime England. Eleanor noted that while they dined off gold and silver plates, they ate the same rationed diet as everyone else in the country. In her bathroom a black line running around the bathtub indicated how high she could fill the tub. With limitations on the use of the fireplaces, the ornately decorated rooms were uncomfortably cold.

Mrs. Roosevelt inspected the damage that German bombs had done to the palace and at the King’s request accompanied the royal couple on a tour of their devastated city. The extent of the ruins caused by the blitz shocked the First Lady.

After two nights at the palace, she moved to the vacated lodgings of the U.S. ambassador and began her tour of the countryside. Her itinerary included visits to factories, farms, airfields, shipyards, American and British bases, and hospitals. It was in England that she began the practice of asking soldiers if they would like her to write to their loved ones when she got home. She would eventually write hundreds of such letters.

The First Lady also became the GIs’ advocate. When she learned that the men were not getting woolen socks and that they were getting blisters from wearing cotton ones, she passed on their concerns to the highest levels of both the military and the government. The supply and distribution of woolen socks got priority.

Lois Laster, a Red Cross worker and eyewitness to one of Eleanor’s visits would later say, “She was a very gracious woman. She didn’t rush in and rush out. She mingled … (and) sat down and talked with the troops.”

The month-long English trip was a tiring ordeal for a woman in her late 50s, but everyone was impressed with her endurance and fortitude, so much so that invitations from other countries began to pour in. Back home in the United States the critics and the press assaulted Eleanor by harping on the expense of the trip (which she had paid for herself), but she was used to criticism and handled it gracefully. Yet, the malice of her political enemies was the reason why she stayed at home for almost a year.

In the meantime, she continued to visit American factories, bases, and hospitals for her husband and was greeted everywhere with friendly and accepting crowds. She also continued her role as hostess to foreign visitors to the White House.

Madame Chiang Kai-shek, wife of the Nationalist Chinese leader who was often in the United States during the war years, traveled with an entourage of 40 people to tend to her security and every need. She marveled at how Eleanor could travel anywhere and everywhere in the country accompanied only by her friend Tommy.

In the summer of 1943, FDR began to consider invitations for a visit from the governments of Australia and New Zealand for a visit. He did not think that he could afford to spend the time away himself but believed that it would be useful for Eleanor to pay them a visit.

When he approached his wife with the idea of traveling to the two countries, she requested to visit America’s island bases as well, especially Guadalcanal. Eleanor had visited many wounded men from that great battle in stateside hospitals and felt that it would be important for her to see for herself where they had been wounded or lost their health.

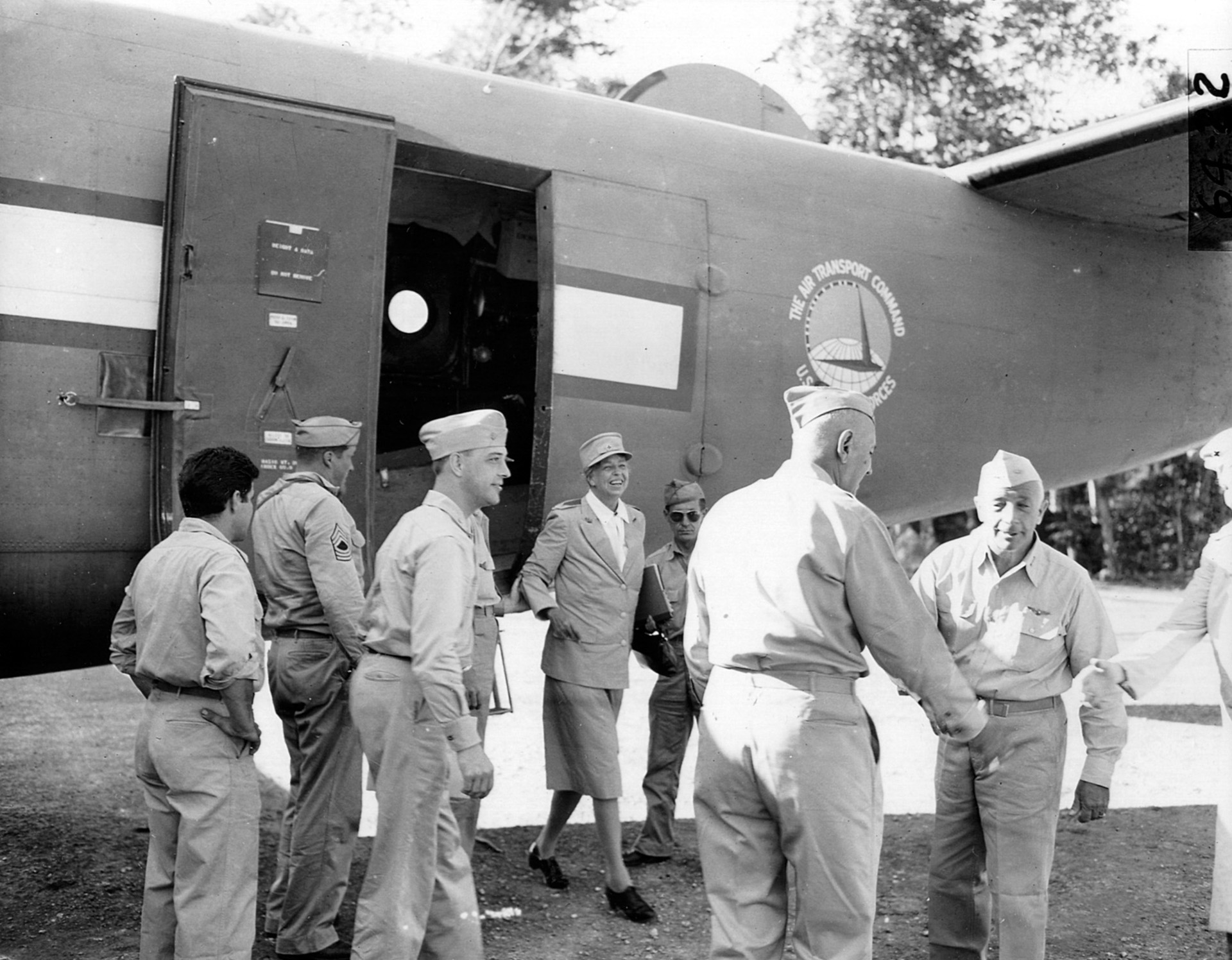

When the plans for the trip were firmed up, she called upon her friend Norman Davis, chairman of the American Red Cross. She proposed to visit Red Cross facilities in the South Pacific. Davis was pleased with the offer and suggested that Eleanor be his official representative and that she wear a Red Cross uniform while on her tour. After discussions with FDR, she agreed to the idea and bought uniforms for the trip.

All the preparations were completed in secret. Further, she decided to go alone and leave her aide and typist Tommy behind. The two had received such criticism from the Republican press that Eleanor thought some of it might be diverted if she went alone. She was wrong. Her profile was too high to avoid criticism of anything that she did.

The night before her departure, she and Franklin were at their New York home, Hyde Park. Winston Churchill was their houseguest at that time as both he and Roosevelt were due to leave for the Quebec Conference the next day.

Eleanor Secretly Flew to Hawii in a B-24 Liberator Bomber

Over dinner Eleanor casually mentioned that she was leaving for the South Pacific in the morning. Churchill was aghast. He was caught completely off guard by the news, but he would wire his people in the British territories that she would visit to take good care of her.

Eleanor secretly flew to Hawaii in the belly of an army B-24 Liberator bomber. There were no heated accommodations for her or the few other military passengers, so the crew offered her blankets to keep her warm in the drafty metal flying box.

The First Lady arrived in Hawaii on August 17, where she was met and hosted by the military brass. However, it was typical of her that she wanted to meet and speak with the ordinary GI. When her caravan came across a stalled truck, she learned that the driver, a young private, was taking a load of 300-pound ice blocks to remote bases on Diamond Head crater. She immediately determined to go with him and announced to her startled and flustered entourage that she would be riding in the ice truck. That done, the officers who had been following her in their army Plymouths hustled to find four-wheel drive vehicles that could make it up the steep grades. As would happen everywhere on her trip, the GIs were glad to see her.

Two days later, she landed on Christmas Island, the first of a series of backwater bases that FDR called “…the islands for guarding the supply route.” The soldiers and sailors were called upon to keep constant vigilance, but there was never any enemy activity to guard against. Boredom was acute, and little was available in the way of diversion. When she landed, an officer told her that she was the first white woman he had seen in eight months.

Eleanor also found that if she wanted to take breakfast with enlisted men (instead of officers) she had to get up before 6 am. Her days rarely ended before 11 pm. Yet, she doggedly maintained a daunting schedule of visits to rest areas, hospitals, and Red Cross facilities, sometimes traveling 40 miles in a jeep to reach remote outposts.

On August 26, on her seventh island stop, she finally reached the headquarters of Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey at Noumea in New Caledonia. Halsey had already been the reluctant host of Congressional and press junkets and was dreading the visit from a woman “do-gooder” whom he was sure would be nothing more than a nuisance.

When they met, Halsey asked Eleanor what her plans were. She at once asked if she could visit Guadalcanal. She had her heart set on it. The Admiral refused. The battle of New Georgia was then raging, and he did not want to spare any of his precious fighters or officers to provide escort for her. He suggested that she complete her visit to Australia and New Zealand first and then return to Noumea. He would decide then. Crestfallen, Eleanor reluctantly agreed. “Ad Halsey seems very nervous about me,” she wrote Franklin.

The next day, she flew to New Zealand. There she made the rounds of government hosted events before visiting hospitals, military bases, and Red Cross offices. She observed the war work of New Zealand women. Her escort was a distinguished Maori guide named Rangi, with whom she hit it off immediately. While touring the country, she received a letter from a New Zealand soldier, which amused her. He asked, “… if I would not see that our men left their women alone.”

On September 3, Eleanor flew to Australia. Relatively few people were on hand to greet her when she landed at the airport, but word spread, and by the time she reached the Sydney city hall a crowd of 20,000 had gathered. Her first round of official visits in Australia was a huge success. The Australians were used to the stiff ritual of visiting British royalty. Eleanor by contrast was warm, personable, and approachable. She then began her ceaseless rounds of hospital visits. Someone estimated that she walked for three miles through hospital wards. As always, she was anxious to see the contributions women were making in Australia’s war effort and visited factories and bases where women were working.

While Eleanor was a hit with the Australian government and people, she was less well received by theater commander General Douglas MacArthur. He did not like sharing the spotlight with any other American, particularly the wife of a man he disliked. If the President sent his wife to meet him, MacArthur would send his wife to meet Eleanor. Claiming that he was too busy with the war to meet her, he sent Mrs. MacArthur instead. When Eleanor requested to visit the troops in New Guinea, he flatly refused saying that it was too dangerous. That vast domain was his exclusive territory.

“It Makes Me Want to do Something Reckless When I Get Home, Like Making Munitions.”

MacArthur’s staff aide, Captain Robert White, was assigned to escort Eleanor around Australia. He was none too pleased with the assignment but came away a changed man. He would later write, “Wherever Mrs. Roosevelt went she wanted to see the things a mother would see. She looked at kitchens and how the food was prepared. When she chatted with the men she said the things mothers say. (She) went through hospital wards by the hundreds. In each she made a point of stopping by each bed, shaking hands, and saying some nice, mother like thing.” She brought many of the hardened GIs to tears. She was especially suited to be motherly to these young soldiers and sailors because all four of her sons were serving in the military.

Eleanor was frustrated by not being able to visit New Guinea and by being hemmed in by generals, admirals and MPs who treated her “like a frail flower.” She wrote to her husband, “It makes me want to do something reckless when I get home, like making munitions.”

While MacArthur was inflexible, Halsey had been won over. When she arrived back in Noumea on September 14, Eleanor found Halsey’s attitude much changed. He had been hearing reports of her work and was impressed. Halsey decided that Eleanor had earned her trip to Guadalcanal.

But Halsey did have a favor to ask. Would she be willing to visit the naval hospitals on the island of Efate? She agreed at once but had to keep the name of the island a secret as the Japanese had never bombed it and the admiral did not want them to know that it was even occupied by the Americans.

The night before her trip to Guadalcanal, the First Lady had but two hours of sleep as she had to catch a plane at 1:39 am to make a cold night flight to the island, which was still being bombed by the enemy. On Guadalcanal the men were not told of her coming, but the night before her arrival they were told that they were not to walk around without wearing pants and shirts, as they often did.

The men on Guadalcanal were completely surprised to see the First Lady. One astonished Marine exclaimed, “Gosh, there’s Eleanor!” Her escorting general was disturbed by the familiarity, but Eleanor was amused. She made the rounds of hospitals, kitchens, a cemetery, workstations, and tent dwellings of the men. Her driver on Guadalcanal was Air Corps Sergeant Joe Lash whom she had known before the war and had requested to see while she was on the island. As they drove along, Eleanor requested that they pick up three skylarking Marines who were hitchhiking. When they discovered the identity of their benefactor, they got quiet, sitting in the back seat until Eleanor started amicably chatting with them. Lash would later write the book Eleanor and Franklin.

During her stay on the island an air raid sounded, and Eleanor joined the troops in a shelter donning a steel helmet until the all clear was given. Though it was a false alarm, Guadalcanal was bombed the night before she arrived and the night after she left. She was as close to the war as she had wished.

Lash noted that on one day of her visit she did not get to bed until after 11 pm and had to be up at 4:30 the next morning. She was 59 years old, and the schedule was exhausting.

When Eleanor took her leave of the island, Admiral Halsey was there to see her off. It was impossible, he told her, for him to express his gratitude for what she had done for the men. He would later write, “I was ashamed of my original surliness. She alone had accomplished more good than any other person, or group of civilians, who had passed through my area.”

During her grueling five-week tour of the South Pacific, Eleanor Roosevelt made 17 stops and talked to an estimated 400,000 people. As soon as she returned home she began the arduous task of writing or calling the parents or loved ones whom the soldiers had requested her to contact on their behalf. It was a labor of love. For months after she flew home, entertainers on the USO tours of the South Pacific would be asked by American servicemen, “How’s Eleanor?”

Author Glenn Barnett, like FDR, is a polio survivor. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History and lives in the Los Angeles area.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments