By Mark Simmons

Major Graf Von Kielmansegg, an officer in Germany’s 1st Armored Division based near Orleans, France, was dragged from a cinema on the night of August 28, 1940, and told to report to his chief of staff. “As I entered his office I was sure that we were finally going to be told that Sea Lion had been given the green light. I asked, ‘Are we on our way?’ He said, ‘Yes, we’re on our way but not to England, to East Prussia.’ So then we knew Sea Lion was a dead duck.”

Von Kielmansegg was right. German Führer Adolf Hitler had decided instead to proceed with Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia, which had killed Sea Lion.

Summer 1940 has obtained something of a mythical quality among the British. Many felt at the time that the Germans merely had to turn up on the shores of Britain to defeat the nation. The average citizen knew little, only what he saw, for example, the antics of members of the home guard parading with broom handles or newsreels depicting a defeated army—having lost all its heavy equipment—being rescued from the beaches by little ships off Dunkirk.

However, on the other side of the hill at Dunkirk, the Germans were as confused in victory as Britain was in defeat.

On July 16, Adolf Hitler, in his role as dictator of Germany and supreme commander of its armed forces, issued his Directive No. 16, in which he stated, “As England, in spite of the hopelessness of her military position, has so far shown herself unwilling to come to any compromise, I have decided to begin to prepare for, and if necessary to carry out, an invasion of England.”

A Confident Nazi Germany

It was nearly six weeks since the ‘Miracle of Dunkirk’ when 338,226 Allied troops were evacuated to Britain, some indeed in small boats and ships, but the majority in destroyers and transports, under continuous aerial attack in heavily mined waters.

The Germans were jubilant that summer. France and the Low Countries had fallen in one of the most brilliant campaigns of military history between protagonists of roughly equal strength. On June 22, the French had capitulated, signing the surrender in the Compiegne Forest using the same railway carriage where the Kaiser’s generals had surrendered to the Allies in 1918. Hitler went sightseeing the following day in Paris and visited Napoleon’s tomb.

A month before, on May 21, Hitler had a meeting with Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, commander of the German Navy, or Kriegsmarine, in which a proposed invasion of Britain was discussed. The admiral asked beforehand how the war was going, but all Hitler could tell him was that “the big battle is in full swing.” Case Yellow, the plan for the attack on France and the Low Countries, was not expected to bring a rapid collapse. Col. Gen. Franz Halder, chief of the General Staff, said before the attack, “If we reach Boulogne after six months’ heavy fighting we’ll be lucky.” They had done that in as many weeks.

But even after the defeat of France, Hitler did not exploit the advantage and attack Britain. Luftwaffe aircraft were told not to infiltrate British airspace. The mood in Berlin, as well as within the German Army, was that the war was virtually over. Most felt the British could be induced to make peace.

The Need For Air and Naval Superiority

When the British rejected Hitler’s peace offer speech in the Reichstag on July 19, the practical problems of an invasion began to loom.

For starters, there were no plans in the High Command of the Armed forces (OKW) for an invasion of Britain. The naval staff had produced a study in November 1939 of the problems such an operation might pose. It identified two preconditions, air and naval superiority, and the Germans in 1940 had neither. The German Army produced a staff memorandum a few weeks after the Navy recommendeda landing in East Anglia. Both these were far from plans.

The Kriegsmarine was poorly equipped for such an undertaking. It had no landing craft purposely built for such an operation. The Kriegsmarine had suffered heavily in the Norway Campaign. All it had available was one heavy cruiser, the Hipper, three light cruisers, and nine destroyers. All other major warships had been damaged or were not yet commissioned.

The British fleet was overwhelmingly powerful. The Kriegsmarine might be able to flank the invasion sea lanes across the English Channel with mines and attack the Royal Navy from the air, but German naval commanders were not confident.

Everything would depend on the Luftwaffe being able to deal with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force (RAF) and still support its land forces. At that stage, the landing was codenamed Operation Lion, but the Germans soon changed it to Operation Sea Lion.

Landing 260,000 Soldiers in Three Days

General Alfred Jodl, chief of operations of the Armed Forces High Command, admitted that the operation would be difficult but felt it was possible to carry it out successfully if the landings were made on the south coast of England.

“We can substitute command of the air for the naval supremacy we do not possess, and the sea crossing is short there,” he said.

The German Wehrmacht wanted to land on a broad front stretching from Ramsgate to the west of the Isle of Wight. The first wave would be some 90,000 men landing in three main areas. By the third day it wanted 260,000 men ashore.

Heavy fighting was expected in southern England. Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch, nominal commander of the German Army, felt the operation would be relatively easy and concluded in a month.

However, the German naval staff had grave misgivings, favoring an invasion in spring 1941. They argued that the Kriegsmarine was far too weak. The weather in the English Channel was unpredictable and presented great hazards for the invasion fleet, which was not designed for such a task. What’s more, the Luftwaffe would be affected by bad weather.

With the Wehrmacht wanting to land at dawn, the periods of August 20 to August 26 or September 19 to September 26 had the most suitable tide tables. The Kriegsmarine would not be ready by August, and in September it was approaching the time of year for bad weather. Even in the best of conditions, the motley invasion fleet would cross the English Channel slower than Caesar’s legions 2,000 years before. The Kriegsmarine expected to lose 10 percent of its lift capacity due to accidents and breakdowns before the Royal Navy and RAF put in an appearance.

Operation Sea Lion on Hold

At the beginning of August, Hitler directed the Luftwaffe to defeat the RAF. The German air fleets failed to gain air superiority over the sea lanes and landing areas and could not prevent the RAF bombing the assembling invasion barges. However, in September they did come close to winning some measure of air superiority over Kent and Sussex. But then Reich Marshal Hermann Göring relaxed the pressure on the RAF Fighter Command by switching his offensive to bombing London.

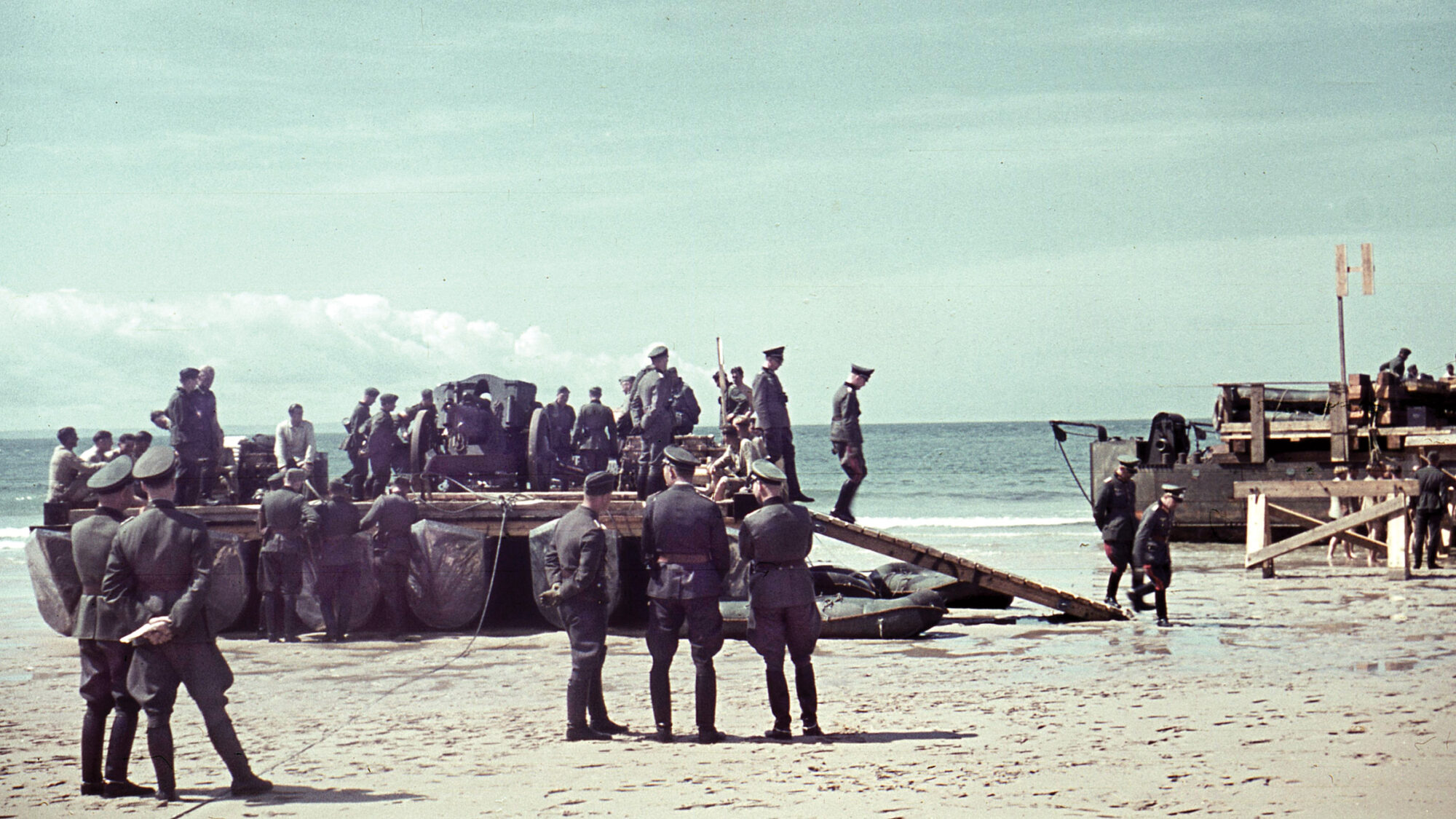

About the same time, the Kriegsmarine had assembled 2,000 barges from the Rhine River and Holland, all of which, although modified, still had poor seagoing characteristics. Nearly all tugs of more than 250 tons were withdrawn from German harbors to tow barges. The Kriegsmarine also assembled 1,600 motor boats and 168 transport ships. By September 21, British air and naval attacks had sunk 67 craft and damaged 173 in harbor.

By mid-September the Luftwaffe had still failed to attack units of the British fleet. Sea Lion was put off from September 15 to September 21. But on the September 17, Hitler postponed Sea Lion indefinitely.

Britain’s Recovery From Early Losses

In April 1940, Britain’s position inviolate behind the Royal Navy received a severe jolt with the loss of Norway, which sea power had seemed unable to influence. What went unrecognized at the time was that this had more to do with a failure of combined operations. And the German Kriegsmarine had been decimated by the Royal Navy in that campaign.

The success of the German blitzkrieg against the French Army in May and June 1940 brought Britain to face the possibility of a German invasion. The chiefs of staff met to address the possibility. With Operation Dynamo, the Dunkirk evacuation, beginning there was little they could do other than recommending the Home Army should be brought to a high state of alert and beach defenses should be given priority.

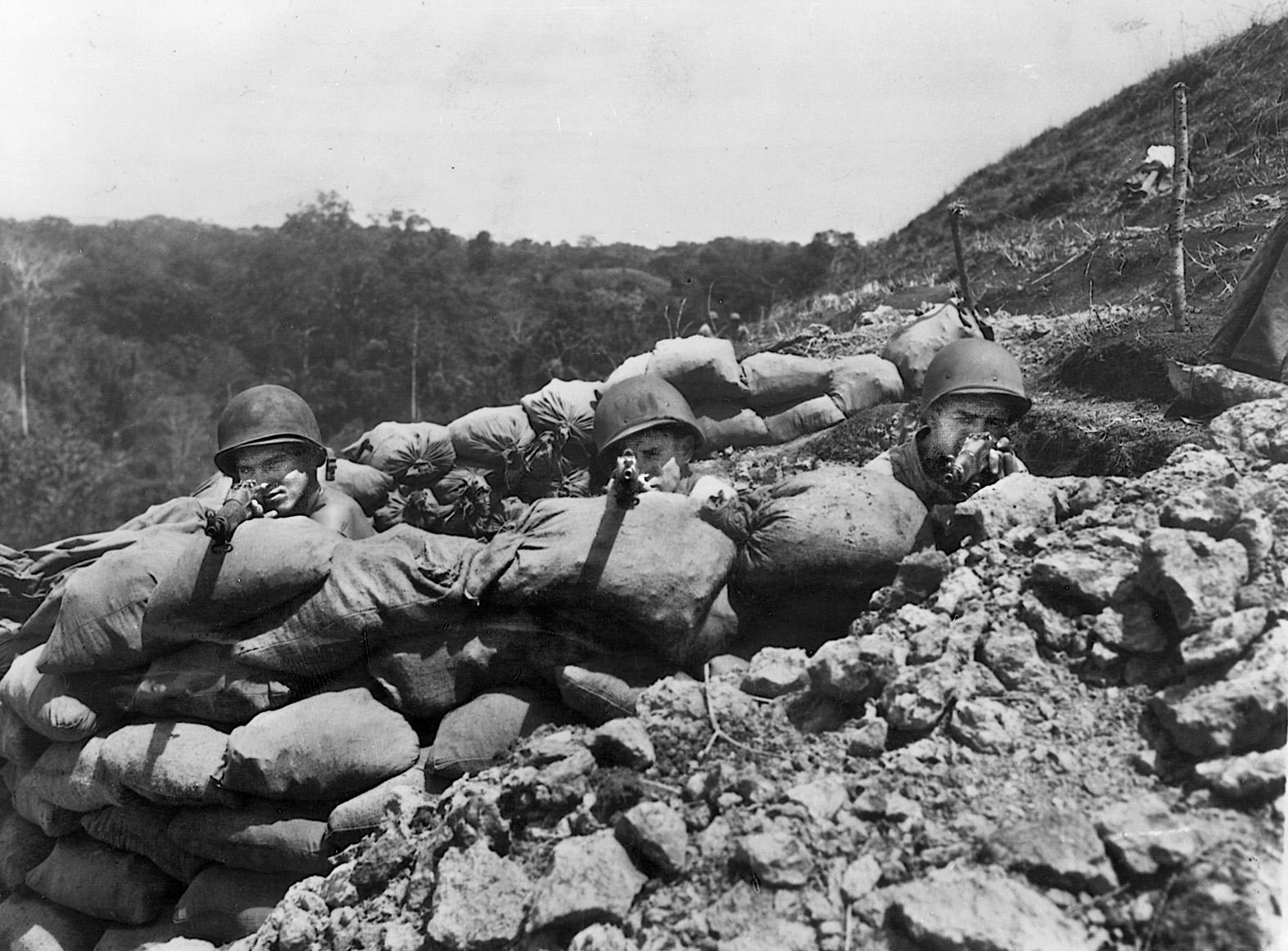

In the face of German air power, evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force was successful. In the United Kingdom there were only 80 heavy tanks, and they were obsolete. There were 180 light tanks armed only with machine guns. There were only 100,000 rifles to equip the 470,000 men of the Home Guard, although 75,000 Ross rifles were on their way from Canada.

The British Army had little chance of stopping the Germans if they had managed to get a large force ashore in June or July 1940.

However, as in previous invasion threats the main defense would devolve onto the Royal Navy and now the RAF. Britain’s Fighter Command had lost many aircraft and pilots in the Battle of France and could muster only 331 Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes. But German indecision and a need to redeploy and refit the Luftwaffe gave Britain a decisive respite.

By September Britain had built up its armored forces to nearly 350 medium and cruiser tanks. Coast defenses were much improved. Strong reinforcements had arrived from Canada. However, General Sir Alan Brooke, Commander in Chief (C-in-C) Home Forces, on September 13 confided pessimistically to his diary that of his 22 divisions “only about half can be looked upon as in any way fit for any form of mobile operations.”

On August 11, the eve of Eagle Day when the Luftwaffe was to launch its offensive to gain air superiority over southern England, RAF fighter command had 620 Spitfires and Hurricanes and aircraft production was exceeding totals called for.

The Defense of Britain: Air, Land, and Sea

For the Royal Navy the advent of airpower posed several problems. No longer could the Navy alone deny the sea to an invader as in 1588 when Catholic Spain attempted to invade England by sea and in 1804 and 1805 when Napoleonic France attempted the same thing. The Royal Navy hoped by the use of bombardment and mines to attack the invasion fleet before it even left its ports. If such attacks were not decisive, it would attack the invasion flotillas as it arrived off the English coast. The Luftwaffe would be stretched to the limit.

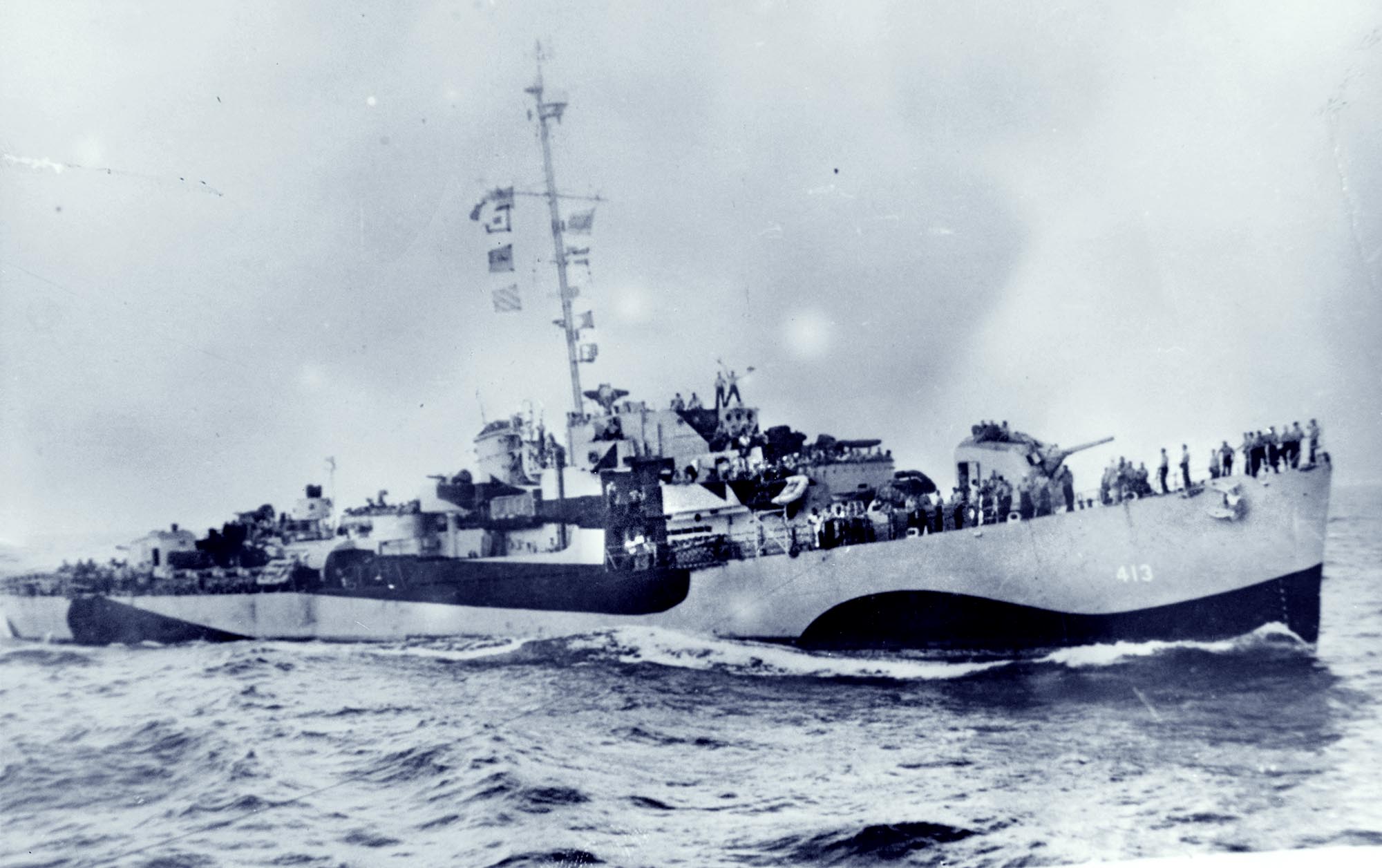

As the invasion beaches were not known, the Royal Navy needed to cover an area from the Wash to Newhaven. It had the strength to carry out that mission. The British Admiralty contemplated “the happy possibility that our reconnaissance might enable us to intercept the expedition on passage.” Given the speed of the invasion barges, taking 12 hours to cross the Channel was a near certainty. The main forces to be used were destroyers and light craft, with close support of cruisers. It was agreed that the battleships should only come south if German invasion transports were escorted by heavier German ships.

Admiral Sir Charles Forbes, C-in-C for the British Home Fleet, argued that so many ships should not be pulled away from the very real German threat to the convoy routes. Forbes kept his battleships, but many of his cruisers and destroyers were dispersed in ports around the southern and eastern coasts. Forbes was proved right with so many ships committed to static roles. Losses among the convoys began to mount.

The RAF also had a vital role in defeating an invasion. Bomber Command would attack shipping as soon as it began to assemble. Once the invasion began, Fighter Command would move to the offensive against troop-carrying aircraft and supply air cover to the Royal Navy attacks on enemy shipping. Coastal Command would support the Navy as well and join Bomber Command in attacking shipping.

Gradually the emphasis and reserves shifted toward southeastern England. Here the sea crossing was the shortest and the beaches would be within German fighter protection. On September 4, a memo warned that if the Germans “could get possession of the Dover defile and capture its gun defenses from us, then, holding these points on both sides of the straights they would be in a position largely to deny those waters to our naval forces.” With this warning the chiefs of staff moved more ground troops into this vital sector.

The End of Operation Sea Lion: Hitler’s Attention Turns East

On September 7, intelligence warned that a German invasion was near. Tide and light conditions would favor the enemy between September 8 and 10. The Royal Navy put all its small craft and cruisers on immediate notice and stopped all boiler cleaning. The RAF moved from Alert 2 invasion in three days, to Alert 1 invasion imminent within 12 hours. It was decided to issue the code word “Cromwell” as a warning to take up battle stations. Unfortunately, a lot of recipients did not know its meaning. Some Home Guard units assumed it meant the invasion had started and rang church bells, which was an agreed warning of invasion, and blocked roads.

The chiefs of staff met in London under Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s chairmanship on September 7, while London was subjected to a massive air raid.

Soon, however, the crisis began to wane. The Germans, stung by an RAF raid on Berlin, switched their attack from RAF fighter bases to London allowing the RAF to make good its losses. The prize of air superiority rapidly slipped away. On September 14, Hitler postponed the invasion until September 17 due to Luftwaffe losses. Then, on September 17, it was postponed again. On September 20, the Germans began to disperse the invasion barges, of which some 10 percent had already been sunk or damaged by the RAF and the Royal Navy.

For the British, the invasion threat remained well into October, but Hitler’s mind was no longer on England, if it had ever really been firmly fixed in that direction. Rather, it was turned east toward Russia.

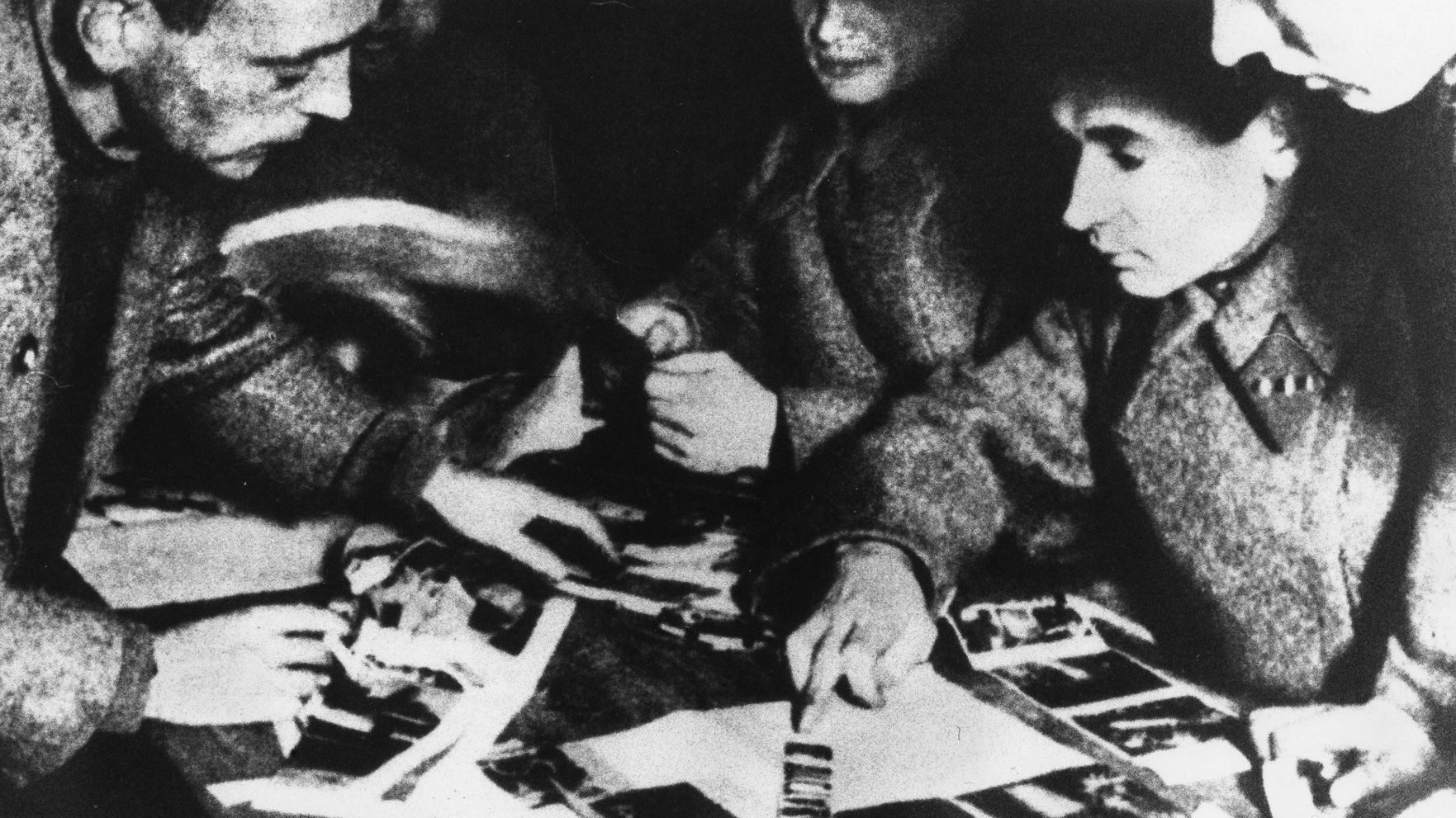

In the 1970s, the Department of War Studies at the Royal Military Academy of Sandhurst made Sea Lion into a war game based on the plans of both sides. A panel of generals, admirals, and air marshals umpired the war game. Any disputes over exact losses were settled by cutting cards. Admiralty weather records were made available, which proved the situation would have been favorable to an invasion between September 19 and September 30. Such findings validate Sea Lion as one of the great “what ifs” of modern military history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments