By Kelly Bell

On December 9, 1941, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, the commander of the Kriegsmarine, lifted all restrictions on German naval attacks against American vessels by his surface and submarine fleets. Atlantic sparring between the two powers had been occurring for several months but would now escalate into full-blown conflagration. For the United States a painful lesson on the consequences of complacency and arrogant refusal to accept outside assistance was coming.

Despite their fearsome reputation, the U-boats commanded by Admiral Karl Dönitz were few in number. When war flared with Great Britain on September 3, 1939, he counted just 57 U-boats, 46 of which were operational. German industry had concentrated on armaments to prosecute a war on land and in the air, and the deliveries of new submarines to the Kriegsmarine amounted to a paltry two per month. Despite this scarcity, ongoing mechanical problems, and unreliable torpedoes, Dönitz’s crews sank over a million tons of British shipping from July through October 1940 in what the submariners called the Happy Time.

The U-boat chief estimated a fleet of 300 submersibles would be required to adequately cut England off from its outside sources of supplies, and with his minuscule fleet’s early successes he may not have been overly ambitious in proclaiming that he might knock Great Britain out of the war before the United States entered the conflict. His hopes rose along with production figures, which later increased to 20 U-boats per month by the time Germany declared war on the United States in December 1941. It was time to show the Americans what they could expect from their adversaries and perhaps even make them think twice about dispatching an expeditionary force to Europe.

If the U-boats could seriously disrupt Atlantic shipping and also sink American supply ships close to their own shores, the losses would be even more demoralizing. Dönitz commenced plans for his first hunting forays into U.S. coastal waters. He called the missions Operation Drumbeat.

Dönitz the Lion

It took a herculean effort by the admiral to scrounge and prepare enough U-boats to make an impression. In December he possessed just 91 operational submarines. Twenty-three were in the Mediterranean, three were en route there, six were stationed just west of Gibraltar, and four were off Reykjavik, Iceland. Thirty-three of the remaining 55 were dry-docked for repairs and maintenance. Eleven more were embarking for or returning from patrols, six were undergoing refit, and five were in the middle of patrols.

Hoping to utilize the long-range Type IXB and IXC boats, Dönitz implored the high command for 12 more IXBs. He managed to get six.

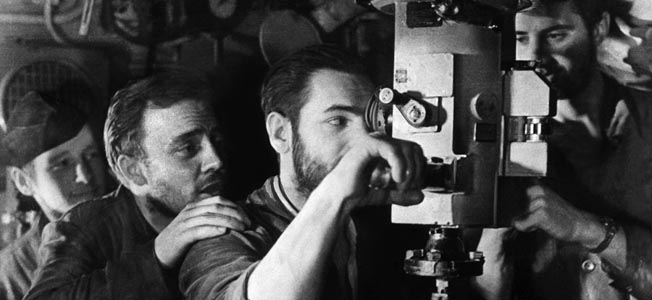

Dönitz’s men called him the Lion. He demanded perfection from his sailors in their confrontations with the enemy. Unsatisfactory performance was not tolerated, but the yearning of his U-boat crewmen to achieve his standards was induced by much more than fear. The Lion never failed to meticulously look after the well-being of his men, assuring that their rations, medical facilities, and overall readiness for combat were the best of the Third Reich’s branches of the military. He was invariably present on the dock at Lorient, France, as his boats embarked on and returned from their voyages, and his sailors’ fervent desire to please him ensured the success of Germany’s submarines early in World War II.

The Sickly Hardegen Takes Command

Kapitanleutnant (Lieutenant Commander) Reinhard Hardegen would play a prominent role in the coming offensive. Originally trained as a naval pilot, Hardegen’s aviation career was cut short by a plane crash in the 1930s that left him with a shortened right leg, permanently bleeding stomach lining, and lifelong diptheria. He was able to stay in his beloved Navy by having himself frequently transferred a step ahead of his medical transcript, which always arrived at his postings just after he departed. Doctors repeatedly learned of his physical debilities only after he had left their jurisdictions, but on the eve of his country’s first serious strikes against its powerful new enemy his clinical records caught up with him.

Hardegen had told Admiral Hans-Georg Friedeburg, a lieutenant of Dönitz, that he was “fit to return to the sea,” without specifically mentioning U-boats, which had little room for sickbays. When Hardegen repeated this clever wording to Dönitz,who had been grimly poring over the medical report, the admiral was impressed and amused by his fearless young commander’s desire and ambition. Despite describing Hardegen as “pale as a boat’s wake,” Dönitz had to admit this was the kind of man he needed at this time. The sickly officer was on his way to America as skipper of U-123.

After briefing Hardegen and two more of his submarine commanders, Richard Zapp of U-66 and Ernst Kals of U-130, Dönitz swiftly but efficiently guided Operation Drumbeat as it began to take shape. These three officers and their commands would make up Group Hardegen. They would steam as soon as possible for the U.S. East Coast and rendezvous with two other U-boats designated Group Bleichrodt. These five submarines would unleash an unprecedented reign of terror on the pitifully unprepared American coastline during the first six months of 1942. It was a campaign that went largely unnoticed by a German populace preoccupied with the Russian front and an American public still in shock over the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and anxiously watching the Philippines. It was nonetheless a monumental clash, and for the men involved it was the center of the universe.

Sailing to the American Coast

At 9:30 am on December 23, 1941, Hardegen’s U-boats, laden with everything from torpedoes to Christmas presents, weighed anchor and churned into the Bay of Biscay. The New World was far from ready for its approaching attackers. No blackouts, radio silence, or other precautions of any note were being employed, and the wolf pack would find excellent hunting.

Just before midnight on the 27th, U-123 crossed the demarcation line of 20 degrees west, where German submariners could finally learn their precise destinations. Opening their sealed orders, Hardegen assembled his officers and showed them the contents: a map of the U.S. East Coast and tourist guides to New York City. With the sudden American entry into hostilities, Dönitz had no detailed navigational material for the U.S. East Coast and was forced to send military personnel to forage through libraries to collect even this much.

Hardegen also learned from the orders that following the initial attacks off New York the U-boats were to move steadily southward, assaulting shipping until reaching Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, where their fuel would be running low, necessitating a return home.

The crew settled into a routine over the next few days as they steamed uneventfully across the Atlantic. Then, at 4 am on January 2, a wireless transmission arrived instructing Hardegen to attack a Greek freighter that had broken radio silence and broadcast a distress signal because of a damaged rudder. Guided by the ongoing directions the vessel, Dimitrios, was sending to an approaching ocean-going tug, U-123 advanced to point-blank range late on the night of the 4th, only for her crew to realize at the last second that two destroyers were escorting the Greek ship. Hurriedly backing off without being noticed, Hardegen resumed his westward trek.

Office of Naval Intelligence in Shambles

Although disgusted with himself for not having attacked, Hardegen had likely saved his U-boat. The Drumbeat boats were already being tracked by British naval intelligence. The dispatch informing him of Dimitrios’s position had been intercepted, decrypted, and passed on to the Canadian Navy, accounting for the destroyers’ presence. In fact, all five submarines were being plotted on their transatlantic passages by Royal Navy cryptanalysts at their headquarters in the town of Bletchley, 50 miles northwest of London.

Bletchley-based U-boat tracking specialist Rodger Winn was familiar with U-123 and even had Hardegen’s dossier. He knew this German was aggressive and independent and that Dönitz had recently begun pulling his U-boats from the high seas convoy routes despite heavy losses off Gibraltar. Abandoning the mid-Atlantic shipping lanes at a time when he no longer had sufficient reserves to withdraw from other theaters to replace those removed from North Atlantic convoy hunting was a baffling maneuver unless the Kriegsmarine was implementing a major strategy change.

Since Hitler had just declared war on America, it did not take Winn long to deduce Dönitz’s intentions. By telling an aide, “Be sure that the people upstairs keep Washington informed,” he made the first of Britain’s attempts to warn her powerful but ill-prepared ally of the approaching peril.

In Washington, the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) was in shambles. Taken totally by surprise by Pearl Harbor, it was also a jumble of unnecessarily complex administrative structures, confusion, and internal feuding. Furthermore, the director of War Plans in Operation, 55-year-old Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, looked upon counterintelligence and espionage with profound contempt and refused to utilize the ONI, whose very capable head, Captain Alan G. Kirk, had resigned in disgust in October 1941.

The commander of the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic Fleet was a hard-drinking 63-year-old admiral named Ernest King. Although his fondness for whiskey and allegedly other officers’ wives called his personal life into question, his diverse service record as an officer experienced in submarines, destroyers, and aircraft was exemplary. King had brought home a Navy Cross from World War I but offset it with another legacy from this conflict—a rancorous hatred of anything British. Also, as one of his daughters later related, “He is the most even-tempered man in the Navy. He is always in a rage.” Finally, King, too, held ONI in the lowest of esteem. All this time Hardegen and his pack were drawing nearer.

Decoding ‘Drumbeat’

At 5 am eastern time, January 9, 1942, U-123 was struggling through a violent marine blizzard 560 nautical miles east of Cape Cod. She had come 2,597 miles, and her men were anxious for some sign of land and targets. Hardegen himself visited the snow-slashed conning tower, and after futilely trying to discern anything through the roiling gray seascape sent his bridge watch below and submerged the boat for some smooth running below the turbulent surface.

When the seas calmed, the skipper ordered the U-boat back to the surface, and radio operator Fritz Rafalski began to intercept American wireless messages from both merchant and military vessels. At 5 pm a message arrived from Dönitz instructing his captains to concentrate on the area from New York City to Atlantic City. Another of the boats, U-125 commanded by Commander Ulrich Folkers, would hunt seaward of Hardegen off the New York and New Jersey coasts, Zapp off Cape Hatteras, Ernst Kals in Cabot Strait off Cape Breton Island, and Heinrich Bleichrodt southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Because of strictly enforced radio silence, Hardegen could not be sure the other U-boats had received Dönitz’s dispatch, but there was no point in worrying about that now since each U-boat was to independently attack targets of opportunity—simultaneously, they hoped, so that stricken vessels could not broadcast news of their attackers in time to save other potential victims. Hastily restationing his bridge watch, the commander eagerly commenced hunting. Soon after night fell on the prowling U-boats, the Operations Intelligence Center submarine tracking room in London stirred to its business.

During the night Winn’s decoding operatives had learned not only of Hardegen’s location and apparent American destination, but also of the mission’s name—Drumbeat. The decoders also overheard another transmission from Dönitz to his men, instructing them that he expected them to be in their attack area by January 13. Because the German submarines were not responding to their chief via radio, Winn had to deduce their definite intentions himself.

Calculating Hardegen’s route from his known position at his brush with Dimitrios and assuming the U-boat was cruising steadily at about 10 knots, Winn figured U-123’s objective was the U.S.-Canada seaboard as far south as Delaware Bay, and if that was where he was headed it was a safe wager his fellow skippers had similarly target-rich destinations in mind. Furthermore, five more Class IX U-boats had just sortied from Lorient. U-boats 103, 106, 107, 108, and 128 were now westbound. Winn headed for his office to telephone Coastal Command and Western Approaches to advise them of the situation.

“Los!”

At 5 am on January 11, Hardegen was reading the sheaves of wireless intercepts from incautious cargo captains whose broadcasts for aid and position fixes following the previous night’s storm were flooding the airwaves. The tempest had done Hardegen’s job for him in at least one instance as the steamer Africander had already been sunk by the rough seas, and at 4:35 that afternoon he was on the conning tower when one of his lookouts spotted the 9,076-ton British freighter Cyclops.

After a slow, careful stalk U-123 was in attack position 1,500 yards from her unsuspecting quarry, and Hardegen handed over the attack periscope to First Officer Rudolf Hoffman, who barked preparatory orders to the forward torpedo room. At 8:49 pm, Hoffman hit the launch button and bellowed, “Los!” Somebody in the torpedo room yelled back, “Failure!”

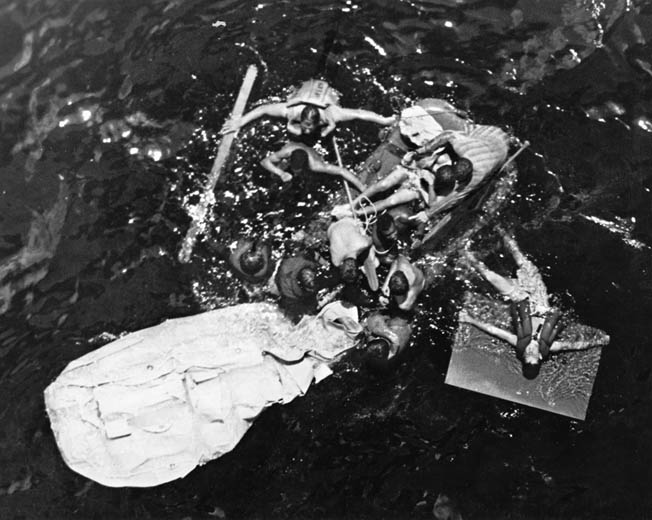

Petty Officer Rudolf Fuhrman slammed his palm against the manual launch button, and the greased missile hissed from its tube as every man on board fell silent and listened. The torturous tension lasted 97 seconds until a muffled explosion shook the sub slightly and Hardegen ordered all deck gun crews to their combat stations. Hoping to silence radio calls for help, the machine gunners opened fire on the antenna array on the steamer’s deckhouse, but the target was still out of range of the bullets. Maneuvering to the front of Cyclops, Hardegen drilled her port side with a stern torpedo just forward of the bridge at 8:18. Five minutes later the ship went under.

In accordance with Dönitz’s orders, Hardegen did not pick up survivors and resumed course for his hunting grounds. Drumbeat was under way, and in the very area Winn had warned about.

“Where is the U.S. Navy?”

Because of the time-consuming sinking of Cyclops and the heavy seas, U-123 did not arrive off New York City until 4:48 on the afternoon of the 14th, when her crew established her position by Long Island’s Montauk Point lighthouse. Cruising on the surface to the mouth of New York harbor, the Germans were stunned when a large vessel steamed casually past as if there was no war. It was the 9,577-ton Norwegian tanker Norness bound for Halifax with a cargo of precious petroleum.

Hoffman fired torpedoes from 800 and 700 yards. The first missed, but the second hit squarely at the waterline below the aft mast. The explosion was a spectacular 50-yard-high column of orange flame as the big ship quickly listed to starboard, but the tilt stopped at a few degrees and the target showed no sign of going down. Cruising to the other side, Hardegen fired a second torpedo into the hull just below the bridge. When this exploded, emergency SOS calls from the stricken tanker abruptly stopped, but the huge hole in the port side apparently counterflooded the vessel and she resumed an even keel. A fourth torpedo malfunctioned and missed. It took a fifth to finish off this fat trophy.

No ships ever responded to the Norness distress signals, and apart from Hardegen’s there is no record of them. The next day a fishing trawler happened to sight a life raft full of chilled survivors and picked them up before sounding the alarm on this attack. The tanker sank in water so shallow that her bow still protruded above the waves. So close to shore and no defensive military action meant that locals were already asking, “Where is the U.S. Navy?”

The man responsible for New England’s coastal defenses was Rear Admiral Adolphus “Dolly” Andrews, commander of the North Atlantic Coastal Naval Frontier. When word reached him of Norness’s demise, the 63-year-old Andrews ignored standard naval procedure decreeing that in such cases every available seaworthy warship be launched for immediate aggressive counterattack. Instead, he launched a cutter, minesweeper, and a few planes to investigate the immediate area of the tanker’s sinking.

Furthermore, the commander of First Bomber Command, U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Arnold N. Krogstad, mysteriously sent his search planes fanning out over a sprawling slice of the Atlantic ranging from 0 to 180 degrees rather than concentrating on the area of 40 degrees latitude, where the attack had occurred. Hardegen should have been imponderably grateful for all the aid afforded him. At the moment, however, he was gingerly negotiating the treacherous waters off Long Island to take up a submerged daylight position at the seaward entrance of Ambrose Channel—the direct route into New York harbor.

U-Boat Attacks Off Nova Scotia

While these Germans passed an uneventful day on the bottom, another U-boat flotilla arrived off Newfoundland and sank the British steamer Dayrose. Also, Kals’s U-130 had sunk the Norwegian steamer Frisco and the Panamanian freighter Friar Rock off Sidney, Nova Scotia, on the 13th.

It was the 19th before Bleichrodt found a target, a medium-sized freighter off Seal Island just south of Nova Scotia. The ship was anchored in 55 meters of water while waiting for a chance to enter ice-choked Yarmouth Harbor. Creeping to point-blank range, the Knight’s Cross wearer fired five torpedoes at the stationary, looming target without touching it. Problems with overcomplicated, unreliable torpedoes were not fully rectified until early 1943. On the 21st, Bleichrodt fired yet another dud at a 6,000-ton freighter off Shelburne, Nova Scotia.

New York City Lights

Still guided only by a tourist brochure, Hardegen was nearing Ambrose Channel at 9 pm on January 14 when he saw a bright light dead ahead. Wondering if he had spotted a target of opportunity, he steered toward the beacon through steadily shallower water. Ignoring his increasingly agitated navigator, Walter Kaeding, who was warning him the light was on the shore, the skipper kept approaching until he saw foamy white waves breaking on a beach just in front of him. “Both back! Emergency full!” he screamed through the hatch. Backing his boat to safety, he turned her away from the rocks and resumed his search for Ambrose Channel.

Unknown to Hardegen, the channel lightship mentioned in his traveler’s pamphlet had been temporarily relocated to Cape Cod, so his search for the floating nocturnal beacon was both fruitless and disorienting. There was, however, the glowing horizon to the west.

Although they were below the narrows and could not see the storied New York skyscrapers, the submariners were awestruck by the luminous heavens above Manhattan. Having visited the metropolis before the war during his around-the-world cadet cruise, Hardegen was stunned at how nothing seemed to have changed from peacetime. New Yorkers were taking no apparent precautions in case of air or sea attack even after losing three ships just offshore.

As the skipper gazed at the glittering vista, he let his eyes wander north to Rockaway Beach and Coney Island and realized he had a golden propaganda opportunity. Hastily summoning the mission’s war correspondent, he had the young man photograph the scene before taking bearings from dead-ahead Sandy Hook, turning away and prowling toward the New Jersey shore.

As they steered away from Sandy Hook, men on the bridge watch were stunned to notice a large, lantern-bedecked tanker following blithely in the sub’s wake. Hoffman leaped to his attack post as Hardegen ordered the boat swung around into a position where the target was silhouetted against the urban backdrop. Flooding No. 1 tube, Hoffman lined up on the ship’s bridge, and at 2,460 feet bellowed, “Los!” The muffled boom of a direct hit came 58 seconds later, and a massive yellowish-red plume erupted from the precise spot where Hoffman had aimed. The stricken vessel quickly listed to starboard.

Through his binoculars Hardegen could see crewmen racing to man an aft gun. With his submarine bathed in flickering light from the blazing victim, he hastily finished her off with a torpedo from a stern tube.

The victim was the 6,867-ton British tanker Coimbra, which went down with the captain and 35 of his crew. Like U-123’s earlier kills, her bow remained jutting above the water, and Hardegen acidly recorded in his log, “The Americans had recalled some of their lightships, so it was a good thing my wrecks were sticking partly out of the water. Otherwise how would other ships find the harbor?”

Long Island residents watched in horror the arching pyre so near shore. At 5 am the Germans turned from their latest kill and headed south. They were still totally unmolested by the U.S. Navy.

Drumbeat’s Toll: 400 Deaths Unanswered

On the evening of January 15, U-123 surfaced after a long stretch underwater to escape rough seas and was immediately spotted by a coastal patrol plane. Hardegen ordered all men forward to add their collective weight to the speed of the emergency plunge. He was the last man off the bridge and had seen the warplane turning toward them just as he grabbed the hatch. There soon came four distinct but distant explosions to starboard as the Americans dropped bombs. Suspecting the airmen might have vectored in more bombers or a destroyer, Hardegen surfaced just long enough to climb back onto the wet bridge and scan the sea and sky with his binoculars.

There was nothing, and the only radio traffic was a bulletin from New York’s Hydrographic Institute declaring the waters around Sandy Hook a danger zone until January 31. The submariners realized the air attack had been a fluke. They had just happened to surface under the bomber. This chance encounter would be the only military resistance they would encounter during the entire mission.

By this time, Admiral King had commenced gathering his scattered destroyers, summoning them from ports, training cruises, and convoy escort duty—not for coastal antisubmarine missions but to accompany troop convoy AT10 on its voyage to Northern Ireland. While U-123 was sinking Norness and Coimbra, the U.S. destroyers Mayrant, Rowan, Trippe, Wainwright, Roe, Gwin, Monssen, Livermore, Charles F. Hughes, Lansdale, Ludlow, Ingraham, and Hilary P. Jones were casually assembling off New York. Hardegen somehow managed to avoid stumbling into any of the warships. None of the U-boats in the vicinity spotted any of the transports and their human cargo.

Twelve destroyers still off the New England coast remained idle until the Bristol embarked for Casco Bay for routine assignment on the 15th and the Ellyson went to New London, Connecticut, for training. The other 10 remained berthed. The opportunity to crush Drumbeat and make Dönitz cautious about approaching U.S. shores again was obvious and potentially easy to exploit, but King did nothing. For lesser negligence the Army and Navy commanders at Pearl Harbor had been fired. Meanwhile, with six torpedoes left, Hardegen was moving south as Zapp and Folkers arrived at their hunting grounds. The slaughter was just beginning.

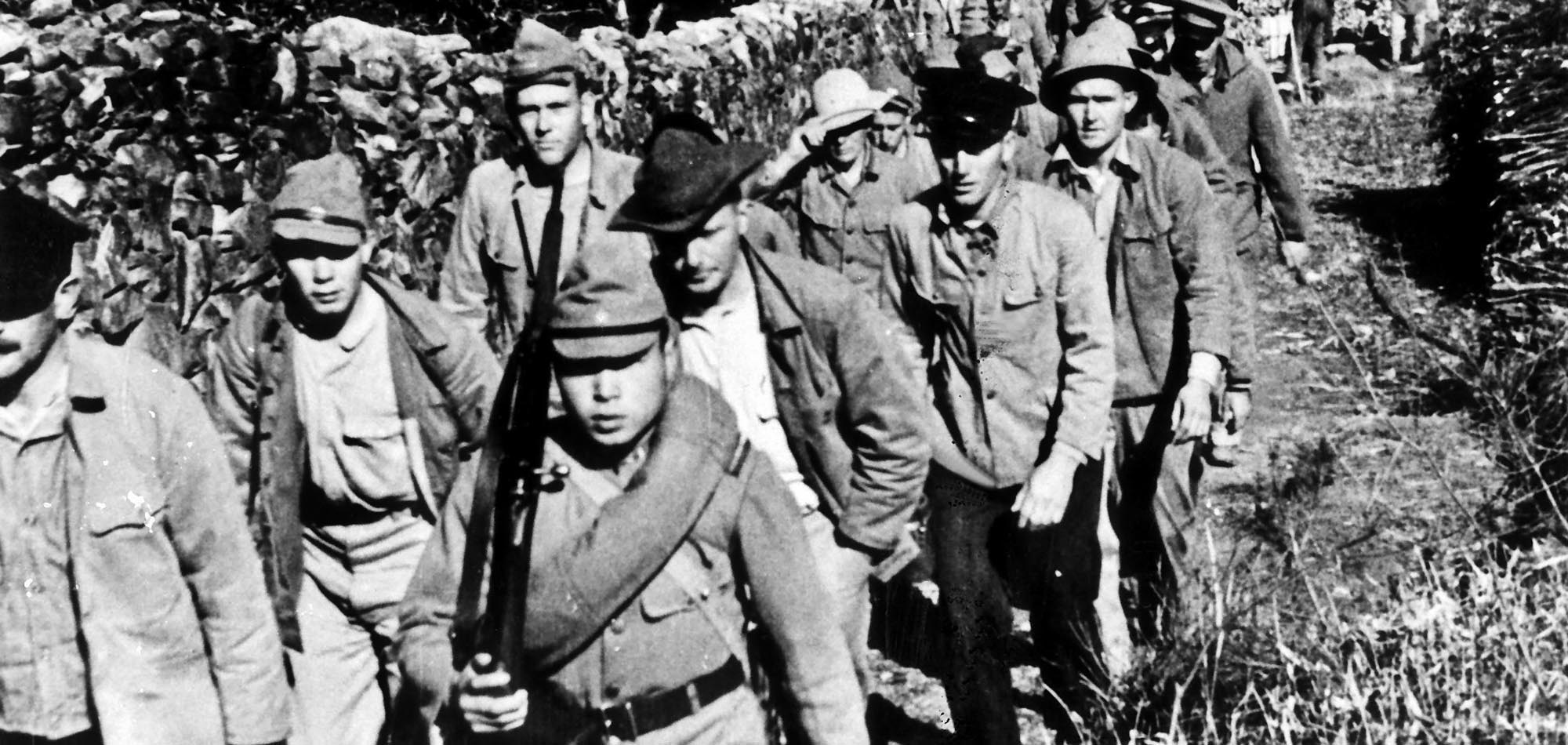

Richard Zapp in U-66 cruised into the risky, shoal-bisected sea-lanes off North Carolina on January 16. Two nights later he spotted his first victim as a blacked-out tanker tried to slip through the moonless night northeast of Diamond Shoals. It was the 6,635-ton Allan Jackson, en route from Cartegena, Colombia, to New York with 72,870 barrels of oil. Zapp’s first officer lined up his forward tubes and sent two torpedoes into Jackson’s starboard hull, igniting an offshore petroleum bonfire. The conflagration was so immense and intense that Zapp decided his original intention of picking up survivors to interrogate about the proximity of more targets was too dangerous.

After waiting 20 minutes and watching the tanker break up and sink among its blazing cargo, the Germans turned away and resumed hunting. Jackson went down with 22 of her 35-man crew. The following night Zapp deliberately sank the 7,988-ton Canadian passenger-cargo ship Lady Hawkins. A total of 162 of the ship’s 212 passengers and 88 of her 109 crewmen were lost, sending Drumbeat’s death toll to over 400. King had yet to react.

Raiding Off Cape Hatteras

During the night of January 16, Rafalski intercepted a transmission on the 600-meter band that gave U-123’s crew a great deal of amusement. The U.S. Army Air Forces had announced that an American coastal bomber had sunk the marauding U-boat off New York. Apparently the crew of that plane had been as inexperienced at interpreting the results of attacks as they were at launching them. Otherwise, there was little excitement that night as U-123 spotted nothing but a small fishing boat.

The following evening the Germans saw their first hostile warship as an unidentified destroyer passed them on the seaward side off Five Fathom Bank. They were lurking in dangerously shallow water and would have been trapped if attacked. Bracketed between the destroyer and the shore and with very little depth beneath them, they could not have fled out to sea or dove to safety, but the ship steamed past. By 7:13 pm, it was out of sight.

Hardegen later claimed to have sunk a 4,000-ton freighter just before daybreak, but no record of its loss is found in Allied maritime records. Rapidly departing the vicinity, the raiders headed east into deep water for a daylight sprint toward Cape Hatteras where, according to wireless intercepts, excellent hunting was accumulating.

After a defiant daylong surface dash, U-123 arrived off Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, at dawn on the 18th and settled to the bottom in 147 feet of seawater. Breaking the surface at 6:46 pm on January 19, she steered for Cape Hatteras, 50 more miles to the south. Hardegen had five torpedoes remaining, and the coming night’s work would be devastating.

At 9:04, the Germans sighted and attacked a medium-sized northbound freighter, but their first shot malfunctioned and missed. By the time they caught up with their quarry, they were back off Kitty Hawk. This time the torpedo ran true, striking starboard and just aft of the funnel. Hardegen had maneuvered to within just 450 yards of the ship, and seconds after the explosion U-123 was showered with burning debris. This vessel, which went under at map coordinates 36-06N, 75-24W, eluded identification. The raiders did not tarry to pick up survivors because of their rush to investigate a ship’s lights spotted to the south.

Before the night ended, Hardegen and his men bagged the 5,269-ton freighter City of Atlanta, the 3,779-ton freighter Ciltvaira, and using their last torpedo and 10 rounds from their 105mm deck gun, crippled the empty tanker Malay. Forty-six merchant seamen died that night.

62 Ships Sunk in Coastal Waters

There was no excuse for the dearth of destroyer protection along the Eastern Seaboard. During the first four months of 1942, the transatlantic convoy routes were so sedate that sailors lost their fear of U-boats and became casual about showing lights at night. Just one convoy, 0N67 in late February, suffered a U-boat attack, losing six ships. Meanwhile, 62 vessels had been lost to torpedoes in coastal waters in less than two months. In March, 74 went down in the Atlantic west of 50 degrees west longitude.

In northern convoy waters, including the Halifax, Argentia, Hvalfjord, and Londonderry sectors, just 6.33 percent of the sinkings occurred, but 41.7 percent of the destroyer fleet was stationed there. The submarine-infested Eastern Seaboard saw 49.3 percent of the tonnage lost but only had 4.9 percent of the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic destroyers. Through it all, King ignored the accurate Royal Navy intelligence warnings he was receiving.

On January 23, the U.S. Navy lied to the American public, claiming to have destroyed an unspecified number of U-boats off the East Coast. In fact, the four miserably aimed bombs dropped in the general direction of U-123 by a patrol plane were the closest thing to an attack of any kind on a Drumbeat U-boat.

Thus far, Drumbeat was a major success. The largest number of U-boats to prowl the coast throughout January was three, including U-123, Zapp’s U-66, and Folker’s U-125. This tiny fleet killed over 500 seamen and civilians by month’s end, and as these U-boats turned for home their replacements began arriving.

156,939 Tons

After leaving the burning Malay, U-123 was spotted and pursued by the mammoth Norwegian whaling factory, Kosmos II, which was operating as a tanker. Its skipper, 36-year-old Einar Gleditsch, tried his best to ram the sub. At 16,966 tons, Kosmos II was the biggest cargo ship afloat and would have smashed the U-boat like a beer can, but Hardegen’s frantic engineers were able to sufficiently patch up an ailing starboard engine to gain a one-knot edge in speed over their pursuer.

Hardegen stood in his conning tower capriciously firing flares onto the whaler’s bridge less than 100 yards behind. Unable to submerge since this would have slowed them enough for their pursuer to catch up, the Germans had to outdistance their foe on the surface. The Norwegians, upon sighting the sub, had immediately broadcast to the Navy information on its location and heading. One hour and 50 minutes later, a plane appeared and buzzed the area where the U-boat had last been sighted, but by then it had reached deep water and safety.

Hardegen alone had sunk nine ships totaling 40,898 tons on this first American cruise, and on January 25 the homebound warriors sighted the 3,044-ton British armed steamer Culebra and sank her in a dramatic exchange of deck gunfire during which the Germans’ 20mm gun exploded and badly wounded their war correspondent, Alwin Tolle.

Culebra had been carrying disassembled Royal Air Force planes, making her a valuable kill. After giving her survivors rations, bailing buckets, and a navigation fix to Bermuda, Hardegen and his men resumed their return trek in high spirits. They had just been notified via wireless that Hardegen was to be awarded the Knight’s Cross on his arrival in Lorient. U-123’s entire crew would be well feted.

Two days later, her men again used their deck guns, sinking the 9,231-ton tanker Pan Norway. It took two and a half hours of pounding from 105mm and 37mm cannon to finish this latest victim.

On the night of February 6, Bleichrodt in his U-109 sank the 3,531-ton Panamanian steamer Halcyon off Bermuda then turned for home, bringing Drumbeat’s first phase to an end. The five U-boats had bagged 25 ships totaling 156,939 tons.

Return to the American Coast

At the beginning of March, U-123 and her men were ready for their second U.S. patrol. During their absence, the replacement U-boats had destroyed 48 ships weighing 281,661 tons, and U-156 commanded by Kapitanleutnant Werner Hartemstein had even shelled the Lagos oil refinery on the Dutch island of Aruba in the Caribbean.

The U.S. Navy had tardily beefed up its presence in destroyers, coastal patrol craft, and observation blimps, but Dönitz had confounded the cryptanalysts by implementing his new Triton code. The reeling Allies had no way of knowing that Hardegen was returning. This time he would prowl the shipping lanes off Virginia.

Late on the night of March 2, under a total eclipse of the moon, U-123 slipped out of Lorient. On the morning of March 22, she sank the 7,034-ton Muskogee, bound from Venezuela to Halifax with a load of crude oil. The Germans were still a full 600 miles east of Cape Hatteras.

Early on March 22, Hardegen sank the brand-new 8,150-ton British tanker Empire Steel, which went down in a horrifyingly spectacular explosion of high-octane fuel. Then, late on the night of March 26, came an adventure new to every man on board.

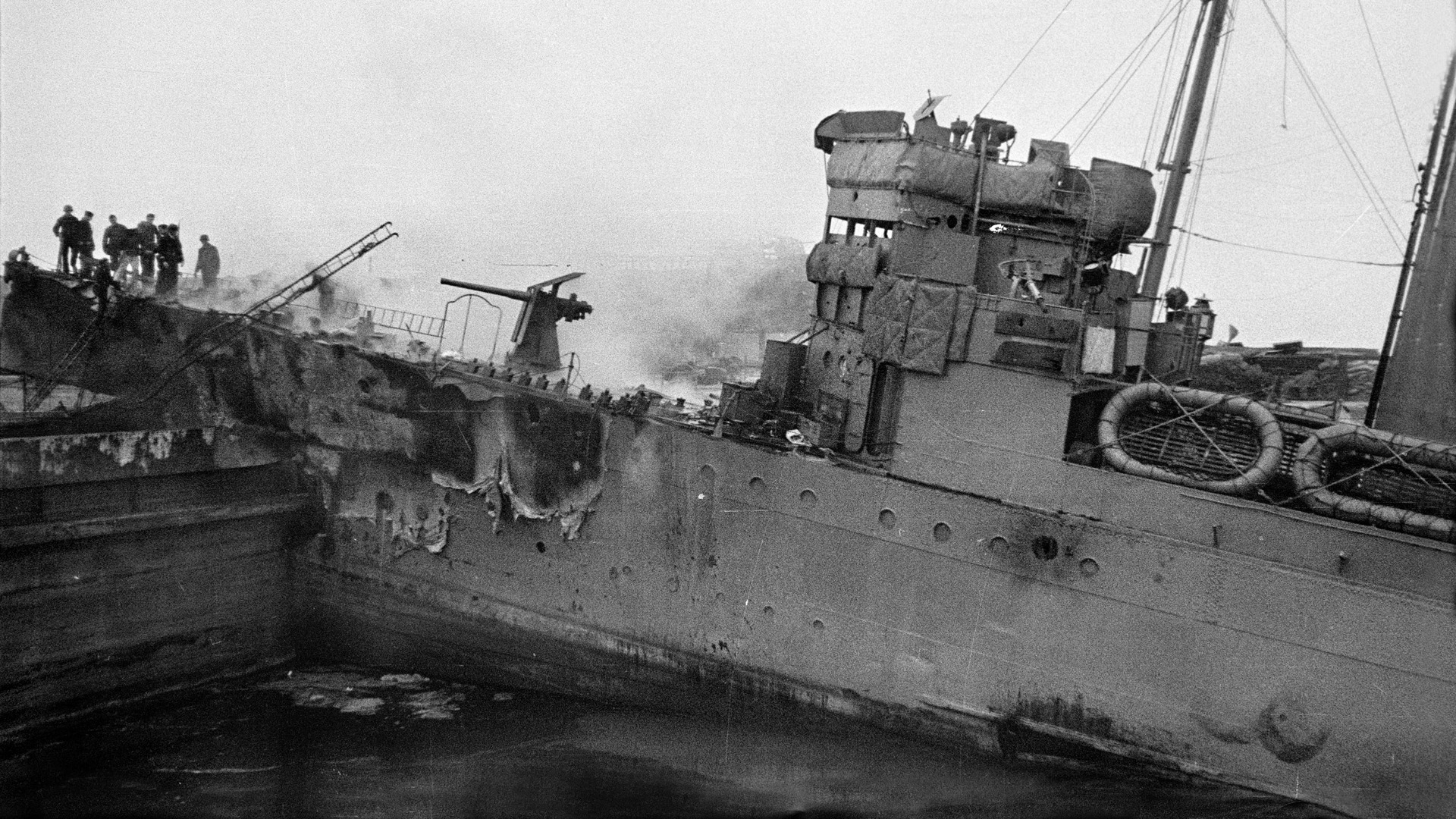

In World War I the British had great success with their Q-boats. These innocuous looking freighters carried hidden deck guns, depth charges, and machine guns and had their holds packed with timber to assure maximum buoyancy. When Hardegen came across the USS Carolyn, he casually torpedoed her just fore of the bridge, then watched as the deck housing fell away and revealed guns. With the torpedo having done little damage, Carolyn swung toward her attacker and opened up with every gun she had while U-123’s gunners were emerging to man their own deck weapons. The new war correspondent, named Holzer, had come on deck to take a look and came to grief even more quickly than his predecessor as a burst of automatic gunfire nearly ripped off his right leg at the hip.

Carolyn’s inexperienced gun crews could not hit their target as it submerged and took off at full speed. U-123 was shaken but undamaged by the exploding shells and depth charges, and, unknown to the U-boat hunters, she was swinging around for another attack. Seething with rage, Hardegen flooded his No. 1 tube and from a range of just 500 yards shot a torpedo into Carolyn’s engine room at about 11 pm. About this same time, Holzer bled to death.

An hour and 20 minutes later the burning ship’s ammunition ignited and blew her apart. After burying their youthful comrade at sea, the grim submariners resumed their patrol. They were headed for Diamond Shoals. Meanwhile, it took nine hours for the U.S. Navy to respond to Carolyn’s distress calls and dispatch a destroyer, bomber, and tug. No trace of the ship, her assailant, or survivors was found.

Pursued by the U.S. Navy

The coastal shipping lanes were somewhat better patrolled than they had been earlier in the year, and when U-123 surfaced off Hatteras Light on the morning of March 30, Hardegen was surprised at the number of patrol boats and planes. Sinking to the sandy bottom 82 feet down, he spent the daylight hours listening to cargo ships passing overhead and worried that the Americans were finally becoming more vigilant.

After dark, the submariners churned southwest to hunt off Cape Lookout and soon spotted a medium-sized freighter, which escaped when the stern torpedo fired at it veered off course and ran harmlessly aground. The next couple of nights were spent dodging PT boats and planes, and then on the evening of April 3 another of U-123’s torpedoes went haywire when fired at the empty tanker Liebre. The angry skipper ordered his gunners topside and had them cripple the target, but as he maneuvered into position to finish Liebre with another torpedo, a lookout noticed a patrol craft approaching at high speed.

Hastily submerging, the U-boat narrowly missed being cut in two by the warship. After a poorly aimed depth charge rattled but did not harm, Hardegen decided to not press his luck and headed south.

In the predawn of April 5, he incapacitated the tankers SS Oklahoma and SS Esso Baton Rouge off the sparsely populated Georgia Sea Islands. Ironically, both ships were repaired only to be sunk by other U-boats later in the war. That evening, Hardegen sank the state-of-the-art cold storage motor ship SS Esparta off St. Simon’s Sound.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy had finally begun to stir.

Fighting Back Against the U-Boats

King was not alone in his Anglophobia. His chief of staff, Rear Admiral Richard S. Edwards, was likewise inclined. When Winn visited Washington in March to attempt to persuade the Navy to introduce coastal blackouts, numerous shore patrols, coastal convoys, destroyer escorts, and a U-boat tracking center similar to the British example, Edwards icily replied, “Americans wish to learn their own lessons, and have plenty of ships with which to do so.”

Infuriated, Winn exploded, “The trouble is, admiral, it’s not only your bloody ships you’re losing! A lot of them are ours!”

This powerful retort, soon reinforced by the second round of Drumbeat, finally made an impression on King and Edwards. In May, they began taking steps to darken coastal cities,learn the sub-tracking business from Winn and installing deck artillery manned by well trained Navy personnel aboard cargo ships. Although blackouts were never effectively initiated, the other precautions would eventually tip the balance against Hitler’s sea wolves.

For the moment, though, Hardegen and his pack were still having things their own way. On the night of April 10, with only two torpedoes remaining, he scored a direct hit from 2,000 yards on the 8,081-ton tanker Gulfamerica. The Germans surfaced 820 feet from their burning target, which was on its maiden voyage, to finish her off with deck guns. Their first shot ignited a film of oil coating the water around them, but the wind blew the flames away from the U-boat.

Crowds of spectators, bathed in brilliant red, flickering light, watched entranced from the Jacksonville, Florida, beach. U-123 and her muzzle flashes were clearly visible from the shore, but Hardegen did not wait long. He knew the military was unlikely to overlook a sinking this spectacular and might arrive any time. He soon departed southward.

About midnight, a plane spotted U-123 and reported her position to the destroyer Dahlgren, which battered the sub with depth charges. Lying helplessly on the bottom in just 72 feet of water and issuing a telltale stream of bubbles, the boat was a sitting duck for what should have been the U.S. Navy’s first-ever successful attack on a U-boat in World War II, but Dahlgren broke off her attack just as the Germans were preparing to abandon ship. Apparently not noticing the bubbles or perhaps misinterpreting them to mean the sub had been destroyed, the Americans abruptly secured from general quarters and headed northeast at 3:58 am on the 11th.

Hardegen was not finished. He used his last torpedo to sink the 2,609-ton American freighter SS Leslie just before dawn on the 13th, then a couple of hours later set his well-practiced deck gunners on the 2,747-ton Swedish freighter Korsholm, sinking her with a cargo of phosphate. After destroying this neutral vessel, U-123, steaming on just one engine, headed home.

Hardegen had sunk another nine ships totaling 52,336 tons. Operation Drumbeat was winding down, but portents of the easy days’ end were already apparent. On March 1, U-656 was sunk by depth charges dropped by a Lockheed Hudson off Cape Race, Newfoundland. Two weeks later, off nearby Virgin Rocks, U-503 was blown out of the water by a PBY-3 Catalina flying boat.

Just after midnight April 14, the destroyer USS Roper sank U-85 off Nags Head, North Carolina. By July 15, five more U-boats had gone down in American coastal waters. By autumn 1942, the panic along the Eastern Seaboard had subsided.

Although U-123 was again bound for Lorient, her adventures were still not ended. Early on the 17th, she sank the 4,834-ton freighter Alcoa Guide with gunfire 260 miles east of Cape Hatteras.

The End of Operation Drumbeat

After arriving safely in occupied France, Hardegen was whisked to Hitler’s headquarters outside Rastenburg, East Prussia, where the Führer personally presented him with the oak leaves to the Knight’s Cross. During the subsequent dinner, Hardegen sat to Hitler’s right and shocked him by commenting on what he saw as flaws in several policies of the regime. He was particularly concerned with the dearth of aircraft carriers and with Hitler’s obsession with the war in the East while turning his back on the growing threat from the West.

Following a perilous voyage to Norway to have his beloved U-123 extensively overhauled, Hardegen turned over command to Second Officer Horst von Schroeter, then departed for Gotenhafen Training Flotilla where he would serve as an instructor. Aboard U-123 and his earlier boat U-147, he had sunk 23 ships totaling 119,408 tons. His precarious health was failing as persistent diphtheria and his bleeding stomach kept him hospitalized for long stretches. After briefly serving as an infantry commander late in the war, he was captured and imprisoned by the British, who erroneously accused him of being an SS officer of the same name. He was finally released in November 1946.

Led by Hardegen, Operation Drumbeat had taken full advantage of American unpreparedness and resistance to accepting British aid in order to launch a devastating campaign against Allied shipping. Drumbeat’s destructive impact far exceeded the human and material toll of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. During the six months the wolf packs were allowed to rampage virtually unchecked, 397 ships and almost 5,000 men and women were killed.

Eventually, the Allies prevailed in the Battle of the Atlantic despite the best efforts of Admiral Karl Dönitz and his marauding U-boats during Operation Drumbeat.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments