By Johnd Domagalski

On the morning of June 13, 1944, the brilliant new aircraft carrier Taiho weighed anchor and slowly moved out of Tawi-Tawi anchorage in the Sulu archipelago in the southwestern Philippines. The vessel was serving as Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa’s flagship. Departing with Taiho were the sister carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku and an assortment of cruisers and destroyers. The force headed northeast with other elements of Japan’s First Mobile Fleet. Two days later, on June 15, the Pacific island of Saipan in the Marianas was invaded by U.S. forces.

The loss of Saipan and adjoining islands in the Marianas chain would be a critical blow to the Japanese Empire, putting the home islands in range of heavy American bombers for the first time. To counter the American invasion, Ozawa devised Operation A-GO. The battle plan involved luring the American fleet into a position favorable for a Japanese attack. In addition to defending Saipan, Ozawa hoped to win a major victory over the U.S. Navy.

Ozawa’s Battle Plan in the Philippine Sea

Two serious issues hampered Ozawa’s ability carry out such a large scale fleet operation: his overall naval strength and the availability of fuel oil. A shadow of its former self, the Imperial Japanese Navy suffered heavy losses in battles at Midway, Guadalcanal, and elsewhere. However, using a nucleus of aircraft carriers and battleships, the admiral still felt he had enough forces available to make his plan work. The shortage of fuel oil had been brought about by American submarine attacks on Japanese merchant shipping. As a result of the deficiency, Japanese ships were forced to use unprocessed Borneo oil. The low-grade fuel created dangerous fumes and damaged ship engines. In spite of these obstacles, Ozawa pressed forward with his plan.

The Japanese assembled nine aircraft carriers, five battleships, 10 heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a host of destroyers of the First Mobile Fleet to fight the Americans. Blocking Ozawa’s path to the embattled Marianas was the powerful U.S. Seventh Fleet under the command of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. The American force included 15 aircraft carriers, seven modern battleships, and 956 carrier planes. The latter amounted to a roughly two to one advantage over the Japanese.

Wary of a potential Japanese move toward Saipan, Spruance was on guard for a big battle. He was concerned about the possibility that an enemy force might try to move around his ships and strike directly at the invasion fleet off Saipan. Spruance positioned his aircraft carriers to counter that threat.

With land bases in close proximity, Admiral Ozawa knew that the Americans would have to rely solely on carrier-based planes in the Saipan area. Accordingly, his battle plan relied on more than 500 land-based planes, operating from airfields on Guam, Yap, and Rota. Paying special attention to the American aircraft carriers, these land-based planes were to subject the enemy to a series of withering attacks prior to the arrival of the First Mobile Fleet. Ozawa would then use the greater range of his carrier planes to strike before the Americans could reply.

Forming up in the Philippines, the Japanese fleet refueled and moved east. Ozawa and his carriers departed the island group through the San Bernardino Strait, while the main force of battleships emerged from Surigao Strait farther south. Watchful American submarines guarding the Philippines spotted both forces and reported that two large groups of Japanese ships were heading east toward Saipan. The ensuing fight came to be known as the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

The Gato-Class Cavalla

Two days earlier and thousands of miles east at Pearl Harbor, Admiral Charles A. Lockwood studied a map of the Philippines Sea. The American command was on alert to a possible Japanese move to counter the Saipan invasion. As the leader of the American submarine force, Lockwood knew that some of his boats could play an important role in any battle.

The admiral laid an imaginary square over the Philippine Sea and believed that any Japanese surface force intending to challenge the American invasion fleet at Saipan would have to pass through the cube. He directed four submarines, Albacore, Finback, Bang, and Stingray, to patrol 30-mile radii at each corner of the square. He later shifted the shape 100 miles south based on intelligence received. One additional submarine, Cavalla, was not among the initial patrol group but would play a key role in the days ahead. She had already been at sea for weeks.

On her first war patrol, Cavalla departed Midway on June 4, 1944. After pulling away from the submarine tender Holland in the late afternoon, she slowly moved through the channel that led to the open sea. Two planes acting as her temporary escort flew above. After clearing the channel, she made for open sea on a westerly course.

Built by the Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut, Cavalla was put into commission on February 29, 1944, by Lt. Cmdr. Herman J. Kossler. One of 73 Gato-class submarines built during the war, she measured 311 feet in length and had a standard displacement of 1,526 tons. Her maximum surface speed of just over 20 knots fell to under nine knots when submerged. Main armament consisted of 10 torpedo tubes, six forward and four aft, with the ability to carry a total of 24 underwater missiles. A deck gun and a small assortment of light antiaircraft guns were available for use on the surface.

Patrol in the Pacific

After about two months of workups, test dives, and crew training, Cavalla made the long voyage to Pearl Harbor via the Panama Canal to join the war effort. She stayed at Pearl Harbor less than a month before venturing to Midway. For the boat’s first war patrol, Kossler was to prowl along the eastern Philippines.

On June 8, Kossler’s boat entered the 500-mile circle that surrounded Japanese-held Marcus Island. Lookouts kept a careful watch for enemy planes as Cavalla spent the majority of the daylight hours riding on the surface. One day later the submarine had an unusual encounter. “A slight impact was felt aft, and shortly afterwards a whale broached astern in what appeared to be a pool of blood,” Kossler explained. “No apparent change in the propeller beat nor any additional vibration has been noted, so it is not believed any damage was done to the propellers.” Cavalla continued her slow and largely uneventful voyage west.

During the early hours of June 14 the weather began to change. “Seas increasing, barometer dropping steadily,” Kossler recorded. “Took several [waves] over bridge and down conning tower hatch with no serious damage.” The commanding officer drafted a weather message for Pearl Harbor, but the radio operator was unable to send it because of the deteriorating conditions. Kossler decided to ride out the storm below the waves and submerged for much of the day, only surfacing mid-afternoon when the weather seemed to be slowly improving.

At about 7 pm Cavalla received a message about a surface contact reported by the submarine Flying Fish. Kossler immediately set a course for the location. The sea conditions had now improved substantially. “Storm completely past us,” he noted just before midnight. “Increased speed to sixteen knots to make up for lost time.”

In the early evening hours of June 15, Cavalla entered her assigned patrol area. Kossler began to patrol the probable route of the enemy reported by Flying Fish. She was not the only submarine on the hunt for the reported contact. The next morning the patrolling submarine sighted Pipefish. Kossler exchanged communications with the fellow American submarine, and it was decided that the two boats would make a coordinated search with each patrolling on one side of the target’s reported track. Having made no contact by 8 pm, Kossler ended the search and Cavalla continued within her assigned patrol area.

Several hours later, just before midnight, Cavalla sighted a convoy tentatively identified as two tankers and three escorts. It was unclear to Kossler if it was the same group that she and Pipefish had searched for earlier in the day. He spent the early morning of June 17 stalking the convoy but had to abandon his torpedo attack when a fast-moving Japanese destroyer forced him to go deep.

By the time Kossler was able to bring his boat to the surface, the convoy was gone. He unsuccessfully gave chase until receiving orders at about 5:30 pm to move to a different patrol area. Unknown to Cavalla’s commanding officer, the convoy that he had been chasing was one of two tanker trains servicing Admiral Ozawa’s battle force.

Sighting the Japanese Fleet

From the sighting reports transmitted by the submarines, Admiral Spruance knew for certain that the Japanese fleet was on the move. The reports provided the general positions of the Japanese ships, but his search planes were unable to pinpoint the precise location of the enemy carriers. The American reconnaissance planes did see Japanese float planes, indicating the enemy fleet could not be far off. Ozawa spent June 17 at sea moving east, trying to keep out of range of the American carrier planes until conditions were favorable to strike.

Kossler gave up trying to relocate the tanker convoy, but his fortunes were about to change. Just minutes before 8 pm on June 17, Cavalla’s SD radar set registered a ship contact. It was initially nothing more than a small pip on the radar scope. The contact was heading west southwest at a distance of 30,000 yards. “Pip seemed to fade in and out at this range, so put bow to contact and went to four engine speed,” Kossler reported. The range then began to rapidly decrease. “At 22,000 yards other pips began to appear on radar.”

Kossler concluded that his contact was a large task force. It was zig-zagging at regular intervals and moving at a speed of 19 knots. By 8:15 pm, the radar scope was clearly showing seven large pips. Kossler correctly surmised that one was an aircraft carrier and the other six, positioned in two parallel columns, were possibly battleships and cruisers. The aircraft carrier was closest to the submarine at a range of 15,000 yards.

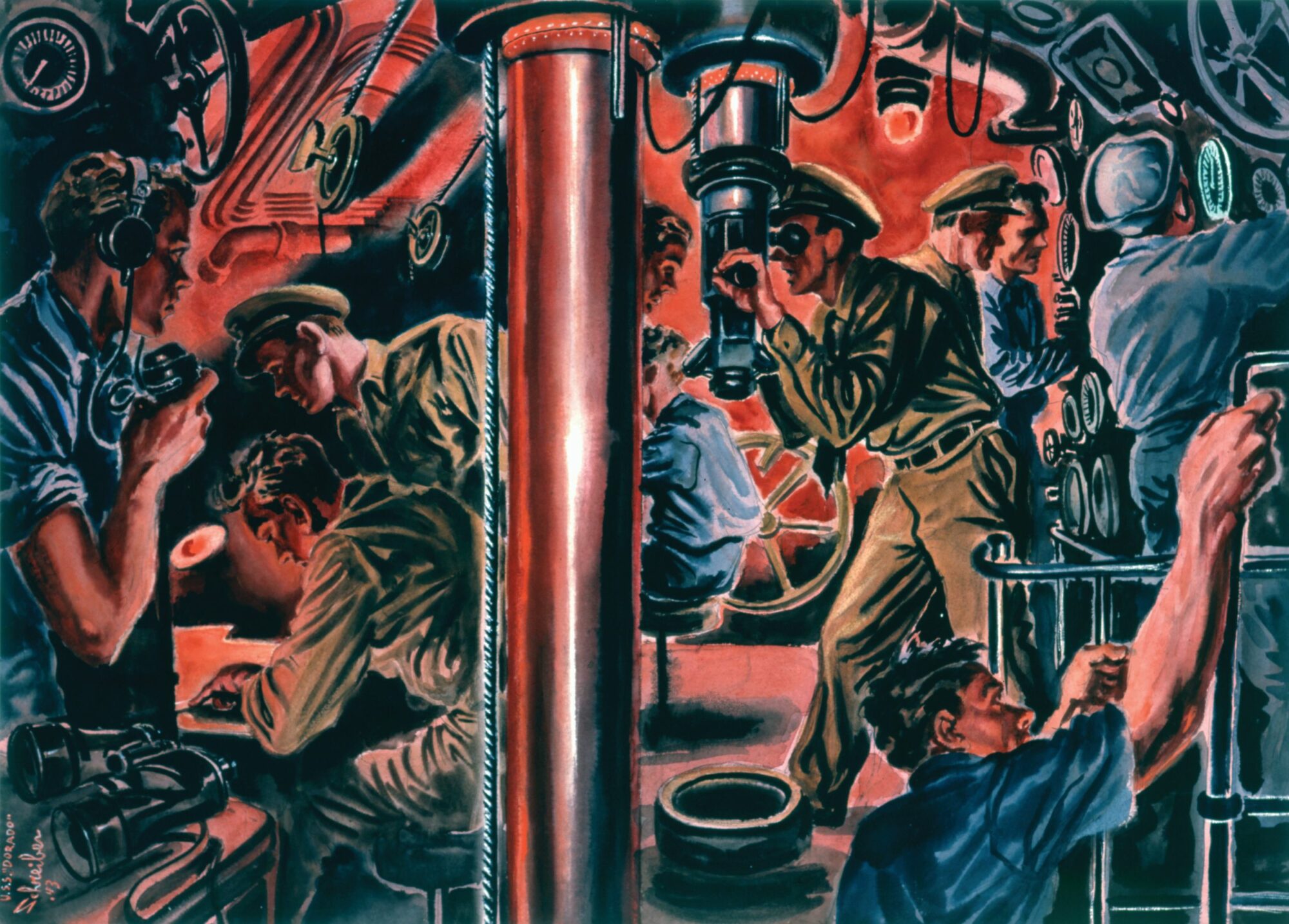

“Although the night was fairly dark, this ship could be seen and looked mighty big,” he later wrote. “We were in position on the track ahead of the formation, so submerged to radar depth and went to battle stations.” While radar was showing seven pips, sound gear was picking up screw noise from 15 different vessels. It was clear that the heavy ships were protected by a bevy of destroyers.

Cavalla’s commanding officer knew he had stumbled on something big. “By now it was apparent that we were on the track of a large, fast task force, heading someplace in a pretty big hurry,” he noted. “Since we had no knowledge of a previous contact report on this task force, it was decided to abandon the attack, and surface as quickly as possible in order to send in a contact report.” It was a difficult decision, but one he knew that he had to make for the greater war effort.

By 9:30 pm, all ships of the task force moved beyond Cavalla except for two fast vessels, assumed to be destroyers, that were mingling near the rear of the formation. “After almost an hour of evading by every method I knew how, managed to get clear of the two ships covering the rear, and surfaced.” Only then was Kossler finally able to send out a detailed contact report to Pearl Harbor.

Stalking the Shokaku

The next day passed uneventfully as Cavalla unsuccessfully tried to regain contact with the task force. At 3:45 am on the morning of June 19, a plane passed low and close over the submerged submarine. The boat crash dived immediately. “It was not sighted,” Kossler reported of the plane, “but the roar of its engines was heard in the conning tower as it passed close aboard from starboard to port. The officer of the deck, Lt. (j.g.) Caslor, was white as a ghost and practically speechless when I reached the control room.” Cavalla continued to periodically sight planes throughout the day, but mostly at safe distances.

At 10:39 am, a group of four small planes was observed through the periscope circling at a low altitude about 15 miles away. Minutes later the noise of surface ships was heard coming from the same direction. Masts were soon spotted on the distant horizon directly under the planes, and the sound operator reported the presence of even more vessels beyond what could be seen through the periscope.

Kossler ordered battle stations and began to cautiously approach the enemy formation. He was astonished the next time he took a look at the targets. “When I raised my periscope at this time the picture was too good to be true,” he reported. “I could see four ships, a large carrier with two cruisers ahead on the port bow and a destroyer about one thousand yards on the starboard beam.”

The lucky Cavalla was in the midst of one of the task forces that comprised the First Mobile Fleet. The group included the carriers Shokaku, Zuikaku, and Taiho, the three largest in Ozawa’s fleet, three cruisers, and seven destroyers. Kossler let the executive officer and gunnery officer take a look at the target carrier through the periscope for identification purposes. The ship was correctly identified as a Shokaku type.

The aircraft carrier that Cavalla was stalking was in fact Shokaku herself. The big flattop was an inviting target. Commissioned in August 1941, the carrier displaced just over 32,100 tons fully loaded. She was manned by a crew of 1,660 officers and enlisted men and could operate 72 planes.

Torpedoes Away

The fluid situation forced Kossler to make some quick decisions. “I could see that the destroyer on the cruiser’s starboard beam might give me trouble, but the problem was developing so fast that I had to concentrate on the carrier and take my chances with the destroyer,” he concluded. The destroyer was Urakaze. From a periscope view, it was clear that she was in a threatening position.

Kossler recorded some details as he carefully studied the carrier minutes before the attack. “The target mounted a large ‘bed spring’ type radar mast on top of foremast, and was flying a large Japanese ensign.” He noted that the carrier was recovering planes. “At the time of attack only one plane was seen left in the air, and the forward part of her flight deck was jammed with planes, my guess at least thirty maybe more.” Kossler’s observation was correct as Shokaku was landing a reconnaissance patrol at the time.

Unbeknownst to Kossler, Ozawa’s task force had already fallen victim to an American submarine attack. Earlier in the day, almost 60 miles away, Albacore put a single torpedo into Ozawa’s flagship Taiho. The ship’s captain deemed it to be minor damage. With speed down by only one knot and the flight deck clear, Taiho continued to sail forward into battle. A victim of poor damage control, she later exploded and sank.

At last it was time for Cavalla to strike. Kossler benefited from such an ideal firing setup that he had only raised the periscope three times during the final approach. At 11:18 am, with Shokaku 1,200 yards away, he gave the order to fire a spread of six torpedoes set to a depth of 15 feet. Although the submarine’s approach was undetected, he still worried about the nearby destroyer. “Angle on the bow of the destroyer was zero, range about 1,500 yards,” he noted at the moment. Kossler gave the order to go deep while still firing the torpedoes. “I fired the fifth and sixth on the way down,” he later recalled.

Cavalla sailors heard the rumbling sound of an explosion about 50 seconds after firing the first torpedo. Two additional blasts came immediately afterward at eight-second intervals. “The last three torpedoes missed,” Kossler concluded after hearing only three sounds. “Put rudder left and rigged for depth charging and silent running.” He now hoped to escape what surely would be an angry Japanese response.

By the time lookouts aboard Shokaku sighted torpedoes approaching off the starboard side, the underwater missiles were already close at hand. The ship’s captain immediately ordered evasive action, but it was too late. The torpedoes struck amidships and forward. Rocked by the series of hits, Shokaku took on a list to starboard and quickly fell out of formation with Urakaze standing nearby.

106 Depth Charges in Three Hours

After launching a devastating attack against an unsuspecting foe, Kossler now focused on escaping alive. He was taking Cavalla deep in the hope of quietly slipping away. The first depth charges exploded a mere two minutes after the torpedoes were fired. “Two salvoes of four depth charges fairly close, first salvo ahead, above and to port, and the second salvo ahead, above and crossing from port to starboard,” he recorded. “Evaded at deep submergence.”

At 11:44 am, a destroyer made a close pass. “High speed screws passed directly overhead and were heard throughout ship,” Kossler remembered. “However, no close charges were dropped on this run.” Dripping in sweat and with wrenched nerves, sailors aboard Cavalla kept as quiet as possible while waiting out the depth charging. “Three destroyers worked on us at first, and after about one and a half hours only one destroyer was left. At no time was pinging heard.”

By 1:30 pm, it looked as if Cavalla was making progress in slipping away from her attackers. “Depth charges began to get further away, but remained between us and scene of attack,” Kossler noted. “About this time JP, which was the only sound gear we had left, began to report loud water noises in the direction of the attack.” Less than half an hour later, Kossler began slowly bringing his boat to periscope depth. Intermittent depth charges were still rumbling in the distance and the underwater sounds continued in the direction of the torpedo attack on Shokaku.

The situation changed suddenly at exactly 2:08 pm. “Four terrific explosions were heard in direction of attack,” Kossler reported. “These were not depth charges or bombs, as their rumbling continued for many seconds.” Cavalla reached periscope depth about 15 minutes later. “Nothing in sight, visibility poor due to rain squalls all around,” he noted of his first look since the attack. “Secured from depth charging and silent running.” Japanese destroyers had dropped 106 depth charges over a three-hour span, with 56 exploding close to the submarine.

Just before 7 pm, Cavalla surfaced and began to leave the area. After traveling for over an hour, Kossler sent a transmission to Pearl Harbor. He reported hitting a Shokaku-type carrier with three torpedoes and told briefly of the depth charging and hearing terrific explosions. He optimistically concluded, “…believe that baby sank.” It was the end of a long and harrowing day.

The Shokaku Goes to the Bottom

The battle-scarred veteran Shokaku had seen plenty of action during the early years of the war, including participating in the Pearl Harbor attack and the Battles of the Coral Sea and Santa Cruz. However, pitifully little was recorded by official Japanese naval sources about her end.

While the commanding officer of Cavalla reported that three of his torpedoes hit the carrier, some Japanese survivors believed that four actually found the mark. It is widely accepted that the detonations ruptured a gasoline storage tank, causing a fire that was initially put under control. A valiant effort was made the save the ship, and she stayed afloat for several hours. However, Shokaku eventually succumbed to a series of tremendous explosions, heard by Kossler and his crew. The detonations may have been caused by the detonation of a bomb magazine or gasoline fumes igniting. The proud aircraft carrier slipped beneath the waves, taking 1,272 crewmen with her. About 570 survivors were rescued by the light cruiser Yahagi and destroyers Urakaze and Hatsuzuki.

Cavalla‘s Well-Earned Rest

Cavalla underwent a tremendous depth charging after firing the torpedoes that doomed Shokaku but was able to escape without major damage. Motors on two pieces of the submarine’s underwater sound equipment burned out during the counterattack, and a ventilation supply pipe flooded. It was a small price to pay for the great achievement of sinking a Japanese aircraft carrier.

The submarine remained on patrol for the balance of June before receiving orders to head for Saipan late in the month. Just after 2:30 pm on July 1, 1944, Cavalla rendezvoused with the destroyer Philip, which served as her escort for the remainder of the trip. The arrival of daylight found the destroyer and submarine close to Saipan. “It was now light enough to see a scene which we will not soon forget,” Kossler recalled. “Practically every type ship in the book was in sight.” Smoke hung over one side of the embattled island as gunfire and explosions could be clearly seen and heard from the submarine.

Cavalla dropped anchor off the southwest side of Saipan in the company of ships of all shapes and sizes. “We were told that Japanese planes generally came over only at night,” Kossler recalled. However, lookouts were positioned topside and machine guns manned to be on guard for the occasional daylight attack.

A group of visitors boarded the boat at 1:10 pm while Cavalla refueled from the tanker Kennebago. “Representatives from the staffs of Admirals Spruance, [Richmond Kelly] Turner, and [Harry] Hill plus six war correspondents and a photographer came on board,” Kossler remembered. “For the next hour I was swamped with questions.” Everyone wanted to know more about his attack on the Japanese fleet. The visitors departed about an hour later, and the submarine made preparations to get underway.

“The stay in Saipan was one of the most interesting experiences I have ever had,” Kossler remembered. “We were only a mile from the beach and had a ringside seat for one of the toughest fights our Marines have had to date.”

On the afternoon of August 3, Cavalla’s first war patrol came to an end when the submarine pulled into Majuro. The patrol lasted 64 days. The boat spent the next month at Majuro with her crew using the time for training and relaxation while the submarine underwent routine maintenance.

Three Japanese Carriers Lost in the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea was such a resounding defeat for the Imperial Japanese Navy that Americans later referred to the one-sided air battle that took place as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. Japanese land-based planes failed to hinder the American fleet. Admiral Spruance found the enemy and struck with a vengeance. In addition to the loss of Taiho and Shokaku to submarines, Ozawa lost a third carrier, Hiyo, and hundreds of planes. A number of other Japanese ships suffered varying degrees of damage.

The last days of the war found Cavalla on lifeguard duty off Japan. She entered Tokyo Bay on the final day of August and remained for the September 2, 1945, formal Japanese surrender. She completed six war patrols and is credited with sinking four Japanese ships. It was, however, her first war patrol and the sinking of Shokaku that was most memorable.

Looking for information concerning the crew of USS Cavalla.

My uncle, Robert F Walker, motor machinist mate, was on the crew of the Cavalla from the time it was commissioned into service at Groton, CT. He was lost to us in an accident whilst stationed at Sub Base Key West, FL shortly after war’s end. How would I determine if he was on the patrol crew when Cavalla SS244 sunk the IJN carrier Shokaku? I’m just trying to put together a more detailed accounting of his Navy service. Many thanks for any info that can be provided.

Patrick Walker

Minden, NV