By R. Thomas Campbell

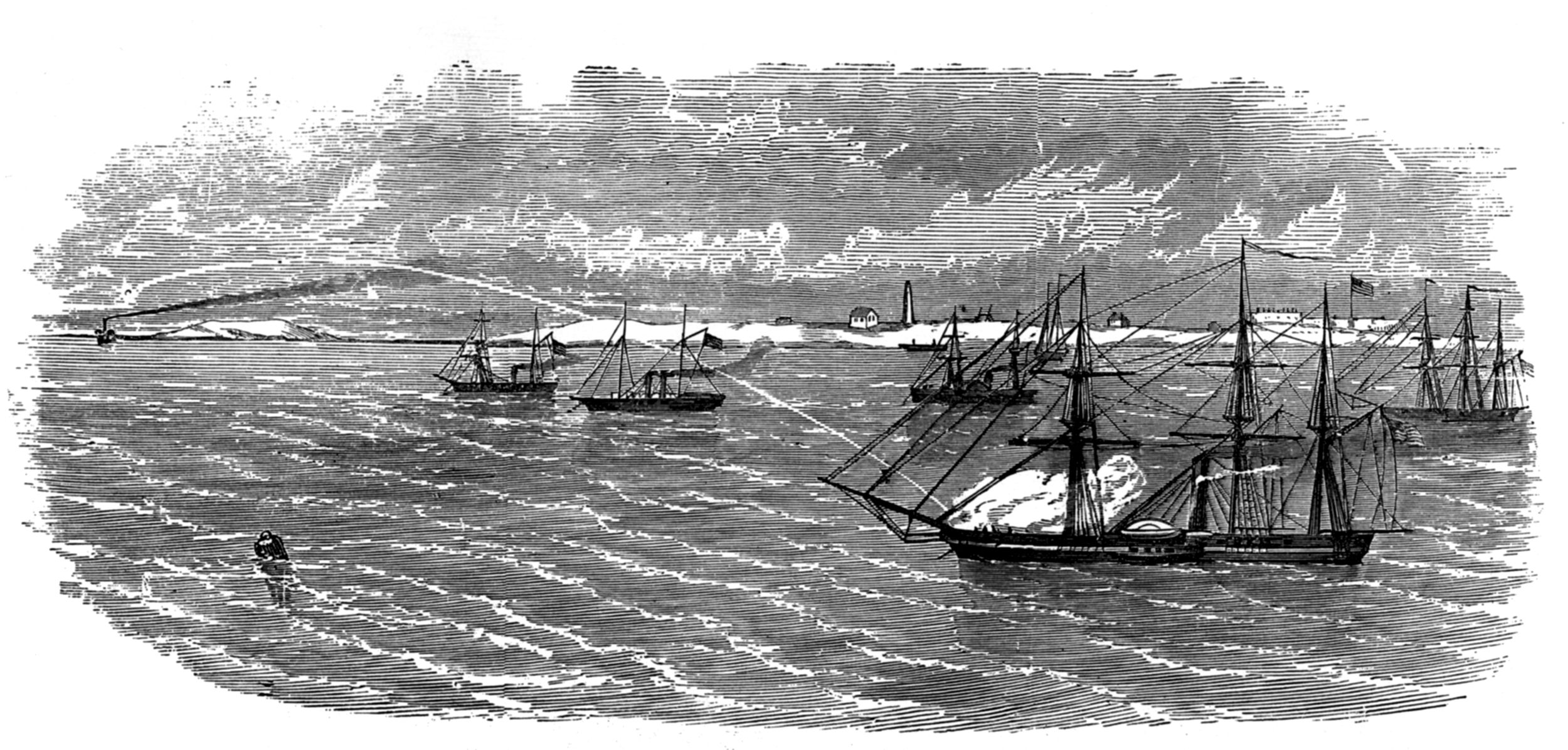

Despite the increasing effectiveness of the Union naval blockade, more and more steamers plied the waters between the few remaining Confederate ports and Nassau, St. George, and Havana during the last two years of the Civil War, bringing supplies and munitions to the hard-pressed southern armies in the field. In 1863, a total of 199 blockade-runners made safe arrivals in Confederate ports. The next year that number increased to 244, with another 30 steaming into port in 1865. To achieve this daredevil record required a special design of steamer, one with high speed, large cargo capacity, and a low silhouette on the horizon. Add to those specifications a brave and imaginative commander, and success was usually, but not always, assured.

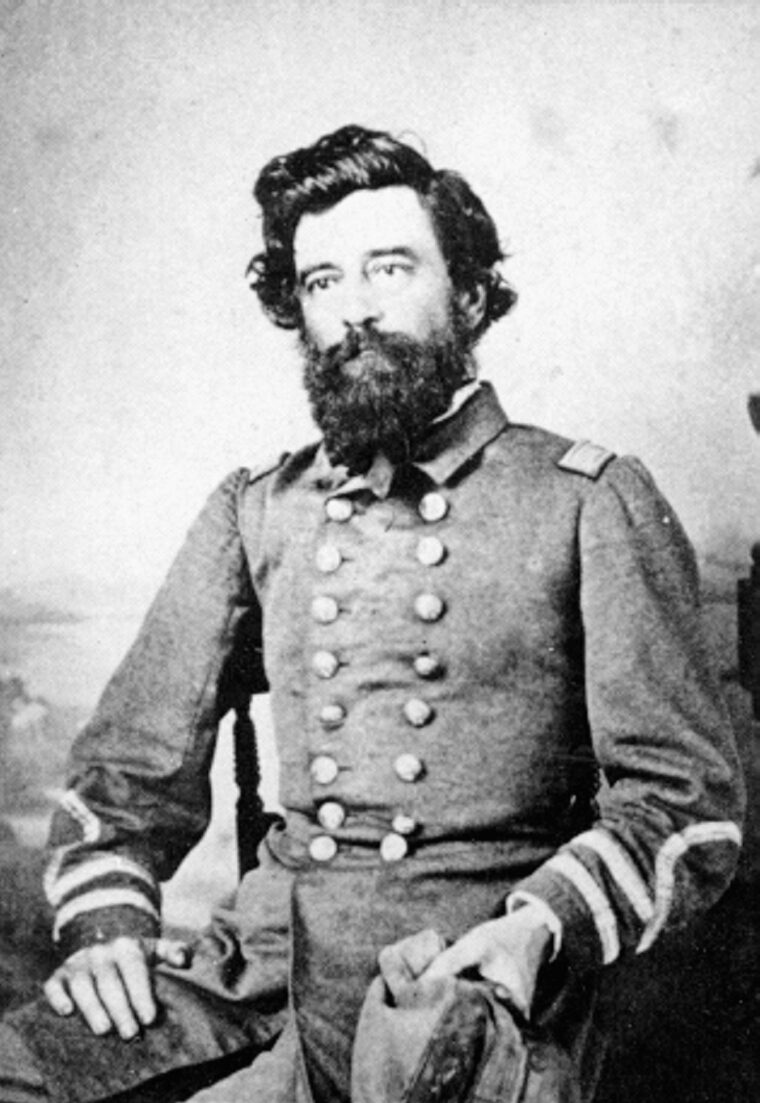

One such commander was English-born Tom Taylor, a supercargo for the Anglo-Confederate Trading Company of Liverpool, England. Taylor managed the loading and delivery of all payloads consigned to the Confederacy by his company. During the war, his steamers compiled an astounding record, successfully completing 49 runs out of 58 attempts. Supervising the operations of nine blockade-runners, Taylor personally made 28 trips to assure the safe delivery of his company’s merchandise. Although sympathetic to the South’s cause and her struggle for independence, Taylor put his vessel and his life in harm’s way not for patriotism, but for the enormous profits that could be accrued by successfully running the Federal blockade. Little did he realize, however, that when the 252-foot Banshee II steamed majestically up the Cape Fear River at Wilmington, North Carolina, on the crisp fall morning of October 15, 1864, it would be the start of his last voyage of the war.

The Banshee II: Pride of the Anglo-Confederate Trading Company

Banshee II represented the state of the art in shipbuilding when she was launched at the Aitken and Mansel facility at Glasgow, Scotland, in the summer of 1864. Advanced in concept, she constituted a class of vessel that would dominate the design of steam-driven merchant vessels well into the 20th century. Grossing 439 tons, Banshee II was 252 feet long with a beam of 31 feet. She drew only 11 feet of water when fully loaded, which permitted her to cross the bar easily at Wilmington. Her steel hull was a light gray, and her giant sidewheels could drive her through the water at over 15 knots. Her 53-man crew, with their English officers and Southern pilots, made the speedy Banshee II almost impossible to catch. She was the pride of the Anglo-Confederate Trading Company, and Taylor was eager to put her through her paces.

Banshee II made three round trips into Wilmington before Taylor had an opportunity to sail on her. Laden with a valuable cargo of cotton, she left Wilmington on December 28, just before the Union attack and eventual capture of Fort Fisher. Taylor’s favorite captain, the competent Jonathon Steele, was at the helm. Accompanied by Frank Hurst, the agent for the Anglo-Confederate Trading Company at Nassau in the Bahamas, Taylor set sail for Havana before attempting a run across the Caribbean to Galveston, Texas.

“When all was ready we experienced the greatest difficulty in finding a Galveston pilot,” Taylor recalled. “Owing to the high rate of pay, numbers of men were to be found ready to offer their services, [but] it was extremely hard to obtain competent men. After considerable delay we had to content ourselves at last with a man who said he knew all about the port, but who turned out to be absolutely worthless. We then made a start, and with the exception of meeting with the most violent thunderstorm, in which the lightning was something awful, nothing extraordinary occurred on our passage across the Gulf of Mexico, and we scarcely saw a sail.”

It is 725 nautical miles from Havana to Galveston. The problem was not so much the distance between the two ports as the lack of transportation from Texas to the rest of the Confederacy. With the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson on the Mississippi River in 1863, very little in the way of supplies could reach the eastern half of the country. Most of the munitions, provisions, and consumer goods arriving at Galveston, therefore, were shipped by rail to Houston, where they were distributed throughout the Trans-Mississippi Department. In March 1865, Banshee II cautiously approached the Texas coast.

“It was a comparatively calm and very dark night,” Taylor wrote, “just the one for the purpose, but within an hour all had changed and it commenced to blow a regular ‘Norther.’ Rain came down in torrents, then out of the inky blackness of clouds and rain came furious gusts, until a hurricane was blowing against which, notwithstanding that we were steaming at full speed, we made little or no way, and although the sea was smooth our decks were swept by white foam and spray. Suddenly we made out some dark objects all around us, and found ourselves drifting helplessly among the ships of the blockading squadron, which were steaming hard to their anchors, and at one moment we were almost jostling two of them. Whether they knew what we were, or mistook us for one of themselves matters not; they were too much occupied about their own safety to attempt to interfere.”

Making a Break For Galveston

Getting into Galveston that night was impossible, so Taylor let Banshee II drift free until she was clear of the enemy fleet. He steamed slowly seaward, shaping a course to make land 30 miles to the southwest at daylight. He dropped anchor in perfectly calm water, the storm having subsided almost as quickly as it had risen. Having seen enough of his new pilot to realize that he was no good whatsoever, Taylor decided to lie off shore all day, keeping a sharp lookout, and that night creep slowly up the coast until he made out the Federal blockading fleet.

Anchoring again for the night, Taylor decided to make a bold dash for Galveston at daybreak. “All went well,” he recalled. “We were unmolested during the day and we got under weigh towards evening, passing close to a wreck which we recognized as our old friend the Will-o’-the-Wisp, which had been driven ashore and lost on the very first trip she made after I had sold her. Immediately afterwards we very nearly lost our own ship too. Seeing a post of Confederate soldiers close by on the beach, we determined to steam close in and communicate with them in order to learn all about the tactics of the blockaders and our exact distance from Galveston. We backed her close in to the breakers in order to speak, but when the order was given to go ahead she declined to move, and the chief engineer reported that something had gone wrong with the cylinder valve, and that she must heave to for repairs.”

It was an anxious moment. Banshee II had barely three fathoms beneath her, and her stern was almost buried in the white water. Taylor released the anchor, but in the heavy swell it failed to hold and the ship began to drift slowly but steadily toward shore. When at length the engineers managed to turn her head, Taylor and the others on the bridge were greatly relieved to see her point seaward and clear the breakers. “As soon as we reached deep water the damage was permanently repaired,” he reported, “and we steamed cautiously up the coast, until about sundown we made out the topmasts of the blockading squadron right ahead. We promptly stopped, calculating that, as they were about ten to eleven miles from us, Galveston must lie a little further on our port bow. We let go our anchor and prepared for an anxious night; all hands were on deck and the cable was ready to be unshackled at a moment’s notice, with steam as nearly ready as possible without blowing off, as at any moment a prowler from the squadron patrolling the coast might have made us out.”

Banshee II had not been lying off for very long when the men on the starboard bow suddenly made out an enemy cruiser steaming toward them. It was a critical time; all hands dashed onto the deck and a man stood ready to knock the shackle out of the chain cable and release the anchor. Fortunately for the blockade-runners, the Union ship did not discover them, and soon disappeared over the horizon to the south.

Under Fire From the Union Blockade

Two hours before daylight, Banshee II quietly raised anchor and steamed on, feeling her way cautiously by the lead. When daylight broke, the men found themselves inside the Union fleet opposite Galveston and prepared to make a short dash for the bar. “We had been under weigh some time, when suddenly we discovered a launch close to us on the port bow filled with Northern blue-jackets and marines,” Taylor said. “‘Full speed ahead,’ shouted Steele, and we were within an ace of running her down as we almost grazed her with our port paddle-wheel. Hurst and I looked straight down into the boat, waving them a parting salute. The crew seemed only too thankful at their narrow escape to open fire, but they soon regained their senses and threw up rocket after rocket in our wake as a warning to the blockading fleet to be on the alert.’

To their dismay, the Confederates discovered that they had not taken sufficient account of the effects of the norther’s effect on the current—instead of being opposite the town of Galveston, they found themselves three or four miles downstream. It was a moment for immediate decision: the alternatives were to turn tail and race back to sea with the Federals’ fastest cruisers in full pursuit, or else make a short but dangerous dash for Galveston under fire. Taylor decided to go for it, and orders to turn ahead full speed were given. To avoid the enemy fleet, Banshee II made a dash for the swash channel along the beach, only to discover that it was nothing more than a cul-de-sac. Shoal waters and heavy breakers still stood between the blockade-runner and Galveston.

By this time the Union fleet had opened fire, and shells were bursting all around the ship. Luckily for the Confederates, the enemy ships were in rough water on the windward side of the shoal and could not employ their guns with any precision. Although Banshee II’s funnels were riddled with shell splinters, she received no significant damage and had only one man wounded. But the worst was yet to come—white water lay dead ahead, and the ship’s only chance was to bump through it. Everyone on board was well aware that if she became stuck fast they would lose both the ship and their lives, for no lifeboats could have been launched safely in such a surf.

“With two leadsmen in the chains we approached our fate,” Taylor recalled, “taking no notice of the bursting shells and round shot to which the blockaders treated us in their desperation. It was not a question of the fathoms but of the feet we were drawing: twelve feet, ten, nine, and when we put her at it, as you do a horse at a jump, and as her nose was entering the white water, ‘eight feet’ was sung out. A moment afterwards we touched and hung; and I thought all was over, when a big wave came rolling along and lifted our stern and the ship bodily with a crack which could be heard a quarter of a mile off, and which we thought meant that her back was broken.”

Banshee II went ahead. The worst was over, and, after two or three minor bumps, she emerged into the deep channel, helm hard a-starboard and heading straight for Galveston Bay, leaving the disappointed blockaders in her wake. It was a narrow escape, but Banshee II steamed gaily up to the town’s wharves , which were crowded with townspeople who had watched the ship’s exploits and cheered heartily for her success.

The Anti-Climactic End of the Banshee II

Taylor, to his disappointment, found Galveston a godforsaken place, its streets covered with sand, its wharves rotting, and its defenses in deplorable condition. The Federals, he believed, could have easily captured the city if they had taken the trouble to do so. But the crew’s welcome was a warm one, and Maj. Gen. John Magruder, commanding the city, boarded the ship for a night of cheerful camaraderie. “We had a capital French cook,” Taylor noted, “and as plenty of game, fish, and oysters were procurable, and our good liquor was plentiful, we had all the necessary ingredients for many most sociable evenings—this was the bright side of the picture.”

The dark side of the picture was that Taylor had to travel all the way to Houston to secure an outbound cargo of cotton for his vessel. This he finally achieved, and after shipment over the worn-out rail line to Galveston, Banshee II cleared Galveston and returned to Havana without incident. By the time she reached the Cuban port, however, the war was over. Taylor sent the speedy runner home to England, where she was eventually sold for less than one-tenth of her original cost. The career of one of the Confederacy’s last blockade-runners ended peacefully, if anticlimactically.

Bat, Stag, and Owl

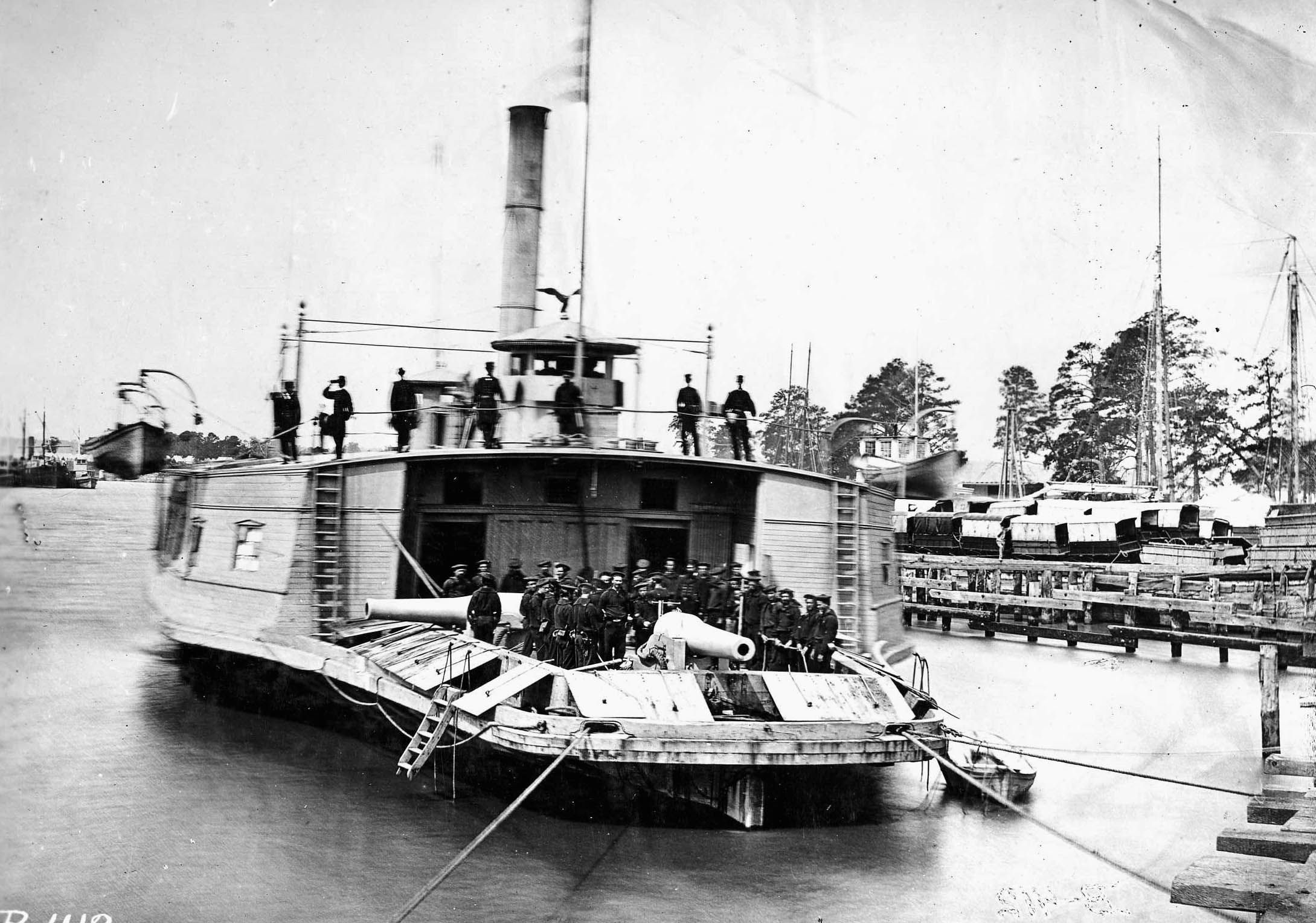

A sister ship, Owl, belonged to a new class of blockade-runners that appeared toward the close of the war. These vessels were constructed in Liverpool, England, under the watchful eye of Commander James D. Bulloch, the Confederate Navy’s agent in Europe. Owned by the Southern government, they included the unimaginatively named menagerie Bat, Stag, and Deer. Owl was a 771-ton sidewheeler with a low, rakishly molded steel hull. She was 230 feet long, 26 feet abeam, and drew 10 feet of water. Her twin Watt engines could drive her at speeds up to 16 knots. She could carry 800 bales of cotton, and her oversized coal bunkers gave her an extra-long cruising range. Being careful to comply with English neutrality laws, Owl was placed under the command of British master Matthew J. Butcher and left Liverpool bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, on July 29, 1864.

Bulloch had personally selected Owl’s cargo. He elaborated on its contents in a letter to Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory, stating that the cargo contained goods for the Navy Department as well as the Ordnance Bureau. Bulloch also explained that he was sending a consignment of wire and a magnetic exploder with 100 fuses for electric torpedoes, the result of successful experiments carried out by Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury.

Arriving at Halifax, Owl attracted the attention of the U.S. Consul, who telegraphed on August 29 that the new blockade-runner was in port and was expected to leave shortly. Two days later, Consul M.M. Jackson rushed another telegram off to the Federal government. “British Blockade-running iron steamer Owl, 330 tons, has just cleared for Nassau with large valuable cargo, real destination, doubtless, Wilmington,” he reported. “Steamer, schooner rigged; has two pipes, one abaft the other. Is long and low and painted light-red color. Takes nearly 100 seamen, probably to supply another vessel at Wilmington.”

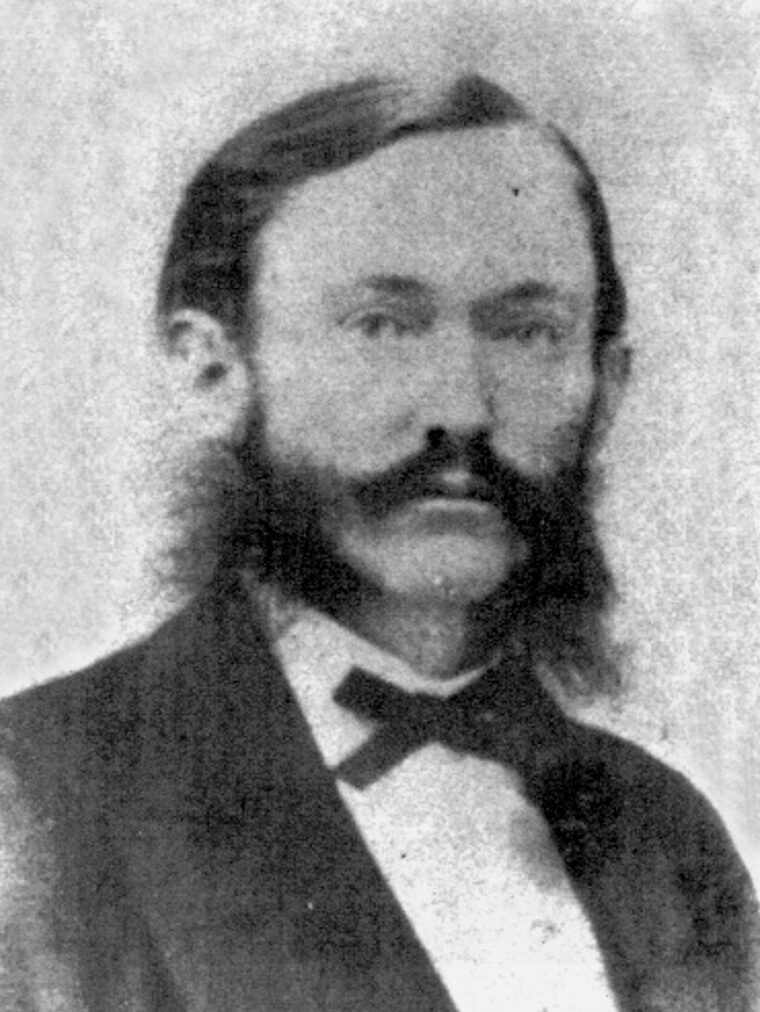

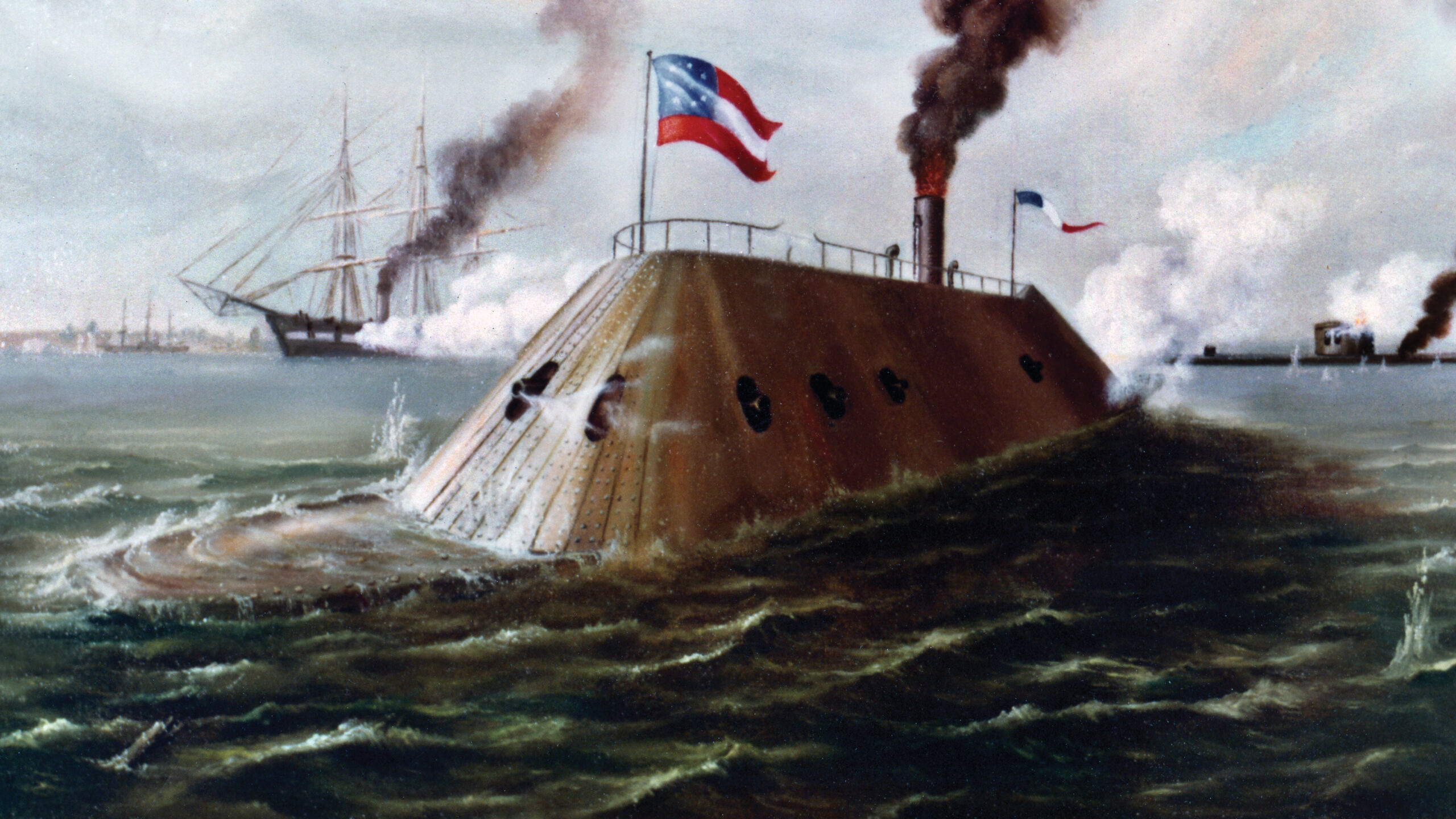

Owl did indeed head for Wilmington, but stopped first at Bermuda to pick up a pilot, arriving in the North Carolina port on September 19, 1864. Ten days prior to Owl’s arrival, Commander John Newland Maffitt received a telegram from Mallory. In it the naval secretary instructed Maffitt to relinquish his command of the ironclad CSS Albemarle in eastern North Carolina and proceed immediately to Wilmington, where he was to report to Flag Officer William F. Lynch. There, Mallory ordered, Maffitt was to take command of Owl. It would be Maffitt’s final command of the war, but it would be several exasperating months before he was able to take her to sea.

While docked at Wilmington, Confederate naval officers attempted to transfer the Owl to government registry, but for some reason Butcher did not consider the process properly executed, and he refused to relinquish command. On the night of October 3, he crossed the bar at the mouth of the Cape Fear and headed for Bermuda with a full load of Confederate cotton. In spite of the moonless night, Federal blockaders quickly spotted the ship and proceeded to send nine shots screaming over and around the speeding Confederate vessel. Several shells exploded in close proximity, slightly wounding Butcher and several crewmen, but Owl reached St. George safely a few days later. Butcher, informed that a Confederate naval officer would soon take his place for the return trip to Wilmington, sailed for Liverpool. First Lt. John W. Dunnington took command of Owl and, guided by the experienced pilot Tom Burroughs, arrived uneventfully back at Wilmington on December 2.

The Worry of Capture

While Maffitt waited impatiently in Wilmington for the transfer of Owl to naval registry, he received a series of instructions from Mallory. The naval secretary was convinced that the most efficient use of the fast steamers now entering the service was to operate them strictly as Confederate Navy vessels, officered and crewed by regular naval personnel. Mallory emphasized that “the Owl is the first of several steamers built for and on account of the Confederate Government, and which are to be run under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy. Naval officers are to be placed in command, and you are selected to take charge of the Owl. As the Owl will soon be followed by several other vessels under this Department, it is important that uniformity, as far as practicable, be observed in their management.”

Five days later, Mallory sent an urgent telegram to Maffitt at Wilmington: “It is of the first importance that our steamers should not fall into the enemy’s hands. Apart from the specific loss sustained by the country in the capture of blockaded runners, these vessels, lightly armed, now constitute the fleetest and most efficient part of his blockading force off Wilmington. As commanding officer of the Owl you will please devise and adopt thorough and efficient means for saving all hands and destroying the vessel and cargo whenever these measures may become necessary to prevent capture. Upon your firmness and ability the Department relies for the execution of this important trust.”

On November 25, Mallory wrote again: “Before leaving port you will station your crew for the different boats of the steamer, having placed in them water and provisions, and also nautical instruments. When capture, in your judgment, becomes inevitable, fire the vessel in several places and embark in the boats, making for the nearest land. The Department leaves to your discretion the time when and the circumstances that must govern you in the destruction of the Owl in order to prevent her falling into the hands of the enemy.”

Although Mallory’s obsession with the possible capture of Owl indicated the desperate straits in which the Confederacy now found itself, the urgent recommendations to a bold and imaginative commander such as Maffitt were unnecessary. Upon the arrival of his new command, Maffitt immediately set out to sea aboard the speedy runner. On the dark night of December 21, he drove Owl across the bar at the mouth of the Cape Fear River and set a course for Bermuda. Stacked in the hold and on deck were 780 bales of valuable southern cotton. Owl, as Maffitt later wrote, “ran clear of the Federal sentinels without the loss of a rope yarn.” Arriving at St. George, Maffitt found several blockade-runners sheltering there, awaiting the results of the expected Union assault against Fort Fisher. By the first part of January, word reached the island that Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler’s assault against the Confederate bastion had failed, and Maffitt prepared to return to Wilmington.

The Disheartening Destruction of Fort Caswell

On January 12, 1865, with her cargo hold stuffed with assorted hardware for the Army of Northern Virginia, Owl stole out of St. George and sped toward the North Carolina coast. On the dark night of the 15th, Maffitt approached Old Inlet at the mouth of the Cape Fear River. Luck was with him. Lookouts spotted only one blockader, and he easily avoided it. Crossing the bar on a high tide at 8 pm, Maffitt eased the big steamer up to the wharf at Fort Caswell. Wisps of smoke spiraled from her twin stacks as crewmen, elated over their easy and successful run through the blockade, rapidly drew the mooring lines taut. Presently, a small boat pulled alongside. The occupants, Confederate soldiers from the fort, had some disturbing news. Fort Fisher had fallen earlier that same day to a combined Federal land and navy force. At that very moment, Southern forces were evacuating Fort Caswell and preparing to retreat to Wilmington. Several Union warships had already crossed the bar at New Inlet and were prowling the river. Owl must leave immediately.

Knowing that he had only minutes to make his escape, Maffitt acted with cool dispatch. As he was about to give the order to slip the chain, his pilot begged for a short delay. He pleaded for Maffitt to wait for 10 minutes while he slipped ashore to check on his ailing wife. Maffitt granted his request, on the strict condition that he return quickly. Giving his word, the pilot bounded onto the wharf and disappeared into the darkness. Maffitt nervously paced the steamer’s deck. Calling the engine room, he ordered the engineer to maintain the highest possible steam pressure and to be ready to start the engines at a moment’s notice. In addition, he ordered the lines cast off and the chain unshackled. Upriver, Maffitt could already see the shadowy forms of several blockaders, and they appeared to be moving in Owl’s direction. The minutes seemed like hours. As steam hissed softly from the engine room, Maffitt once more checked his watch—10 minutes, 15 minutes, they must leave now! Suddenly, the pilot came bounding out of the night. The moment his feet hit the deck, Owl’s big paddle wheels began to turn. The mooring chain let go, her head turned southeastward, and the powerful steamer ran for the open sea. The nearest Federal ship immediately opened fire, her shells exploding around the fleeing blockade-runner, showering her with shrapnel but doing no damage. Soon the speeding Owl was lost in the darkness.

Maffitt had mixed feelings as the throbbing engines drove Owl on into the night. He and his vessel had escaped capture, but with Wilmington gone, he was now completely isolated from his family and his homeland. As Owl steamed seaward, the muffled explosions caused by the destruction of Fort Caswell were clearly audible. Maffitt wrote that they “rumbled portentously from wave to wave in melancholy echoes.” Watching the distant flashes of light, the Confederate commander “in poignant distress turned from the heartrending scene.” It was more than he could bear.

‘Heave to, or I’ll Sink You!’

With his coal supply dangerously low, Maffitt returned to Bermuda under easy steam, entering St. George’s harbor on January 21. He arrived just in time to stop five sister blockade-runners that were preparing to depart for Wilmington. Being the ranking Confederate officer in the islands, Maffitt called 1st Lts. John Wilkinson and John Low to the home of the Confederate quartermaster, Major Norman S. Walker. There, amid the gloom of the most recent news, the three officers discussed possible strategies for reaching the struggling armies with their supplies. Charleston had not yet fallen, and Maffitt and the others determined to sail for that port. “My cargo being important, and the capture of Fort Fisher and the Cape Fear cutting me off from Wilmington,” Maffitt wrote, “I deemed it my duty to make an effort to enter the harbor of Charleston in order to deliver the much needed supplies.”

Accordingly, on January 26, 1865, Owl cleared St. George bound for Charleston. Although several Federal warships were sighted on the departure from Bermuda, the speedy vessel soon left them far behind. Arriving off Charleston in the dead of night, Maffitt placed the government mail and his journal, including his log of his famous cruise aboard CSS Florida, in two weighted bags and slung them over the side on a heavy line. He ordered a trusted sailor to stand by the line with a hatchet—if capture appeared imminent, he was to send the pouches to the bottom of the sea. Several Federal blockaders, freed from their service at Wilmington, now crowded the entrances to the channels leading into Charleston, and Maffitt steamed Owl slowly back and forth trying to locate an opening.

Writing later, he described the nerve-racking effort. “On the western tail-end of Rattlesnake Shoal,” he reported, “we encountered streaks of mist and fog that enveloped stars and everything for a few moments, when it would become quite clear again. Running cautiously in one of these obscurations, a sudden lift in the haze disclosed that we were about to run into an anchored blockader. We had bare room with a hard-a-port helm to avoid him some fifteen or twenty feet, when their officer on deck called out, ‘Heave to, or I’ll sink you!’ The order was unnoticed, and we received his entire broadside, that cut away our turtle-back, perforated the forecastle, and tore up the bulwarks in front of our engine room, wounding twelve men, some severely, some slightly. The quartermaster stationed by the mail-bags was so convinced that we were captured that he instantly used his hatchet, and sent them, well moored, to the bottom; hence my meager account of the cruise of the Florida.”

Instantly, the area was illuminated by burning lights and numerous rockets that sputtered into the blackened sky. Owl was silhouetted in the flickering light as her paddle wheels drove her forward at full throttle. The guns of the blockaders roared, sending shells screaming indiscriminately in all directions. Enemy vessels swarmed everywhere, but owing to the confusion, Maffitt was able to thread his way through the melee. Owl, although badly damaged, finally reached the perimeter of the surrounding blockaders, and with engines still at full power, drove steadily onward into the darkened Atlantic. With no way into Charleston, a disheartened Maffitt reluctantly set course for Nassau.

Owl limped into the Bahamian port, Maffitt recorded, “with a shot through her funnel, several more through her hull, her standing rigging in rags and other indications of a hot time.” The Confederate commander wanted to try running into Charleston again, but while Owl was undergoing repairs, word reached Nassau that the Confederates had evacuated the South Carolina city. Only one southern port remained accessible now—the distant town of Galveston. With a full cargo of essential supplies still on board Owl, Maffit was determined to land it somewhere in the Confederacy. He decided to sail to Havana and, from there, try to reach Galveston. On the way, however, Maffitt agreed to drop off three passengers on the North Carolina coast. Thomas Conolly, a wealthy member of British Parliament, had approached him in Nassau, asking for his assistance in reaching the Confederacy. He was the bearer, Conolly explained, of important dispatches from Confederate diplomat James Mason to the government officials in Richmond. Maffitt, eager to be on his way, agreed, and although the repairs to Owl were incomplete, he steamed out of Nassau on February 23, bound once more for the Carolina coast.

Losing the Cherokee

Just before dawn on the morning of February 26, Owl approached Shallotte Inlet. With much difficulty, in a cold driving rain, crewmen lowered a small boat, and Conolly and two others set out for the sandy shore that was barely visible in the fog and spray. The heavy surf swamped the boat, but the three men, cold, wet, and miserable, made it safely onto the beach. Eventually, Conolly made his way to Fayetteville, where he visited Maffitt’s family before journeying on to Richmond. There he met President Jefferson Davis, dined with General Robert E. Lee, and witnessed the sad evacuation of the Confederate capital.

After dropping off Conolly and the two other passengers, Maffitt steamed for Havana, where he arrived around the first of March. There he found other blockade-runners, including Tom Taylor’s Banshee II, preparing for the long run to Galveston. It took four to five days to steam the 725 miles from Havana to Galveston, and with the prospect of finding no coal at the Texas port, the steamers had to carry enough fuel for the round trip. Only the largest steamers had the bunker capacity to carry that much fuel. Even then, their draft might be too great to allow passage over the bar at Galveston. Owl still had her full load of supplies, and while her fuel supply might be marginal, Maffitt resolved nevertheless to make the attempt.

Before he could start for Galveston, however, Maffitt received orders from the Navy Department to execute one more courier mission. On March 24, he landed Assistant Surgeon D.S. Watson and First Assistant Engineer E.R. Archer on the Florida coast, nine miles from St. Marks. Maffitt left Havana for good in the middle of March. Hot on his heels, USS Cherokee steamed out of the harbor as well. Passing Morro Castle, Owl hugged the western coast, followed by Cherokee. The chase continued for more than an hour. Owl had the advantage of speed and Maffitt’s superior seamanship. Throwing “dust into the eyes” of his pursuer by changing from hard to soft coal and clouding the air with dense, black smoke, Owl steamed past the Federal cruiser and disappeared into the darkness.

Arriving off the Texas port, Maffitt found 16 Federal blockaders guarding the entrance to Galveston Bay. Pressing on in the face of heavy fire, Owl managed to cross the bar, but ran aground on Bird Island Shoals. The enemy commanders were determined to destroy the helpless steamer, and they increased their fire, their shells dropping all around. Maffitt stood on the bridge as exploding shrapnel whizzed about him and coolly directed efforts to free the runner. Her powerful paddle wheels labored in reverse, but Owl would not budge. Union fire became more accurate, and it looked as if all was lost, when someone pointed to a steamer coming out of Galveston Bay. It was the little CSS Diana, captained by James H. McGarvey. Seeing Owl’s plight, McGarvey steamed into the storm of shot and shell and threw her a towline. With Diana’s help, Owl slid off the sandbar and steamed safely into the bay. It was a narrow escape.

“We Must Accept the Verdict”

On May 9, long after the hardened veterans of Robert E. Lee and Joseph Johnston had stacked their arms for the last time, Maffitt ran the blockade out of Galveston and arrived back in Havana. There he received word that all Confederate forces west of the Mississippi had surrendered. Maffitt and his fellow officers had to face the reality that their cause was lost. Deciding that the best course of action was to return to Liverpool and deliver Owl to Fraser, Trenholm and Company, Maffitt left Havana for the long ocean crossing. During the voyage, he maintained a wary eye for Federal cruisers, which were under urgent orders to apprehend him. Stopping at Nassau for coal, Owl reached Liverpool without incident and steamed up the Mersey River on July 14.

The following day, Maffitt gathered the entire crew on the quarter deck and addressed them for the final time as their commander. “This is the last time we meet as sailors of the Confederate States Navy,” he told them. “The Confederacy is dead. Our country is in the hands of the enemy, and we must accept the verdict. I am grateful to you for your loyalty to me, and to the South.” Maffitt then paid off the men, spliced the mainbrace one last time, and to the accompaniment of three resounding cheers from the crew, slowly lowered the Confederate flag. Owl’s gallant little war was over.

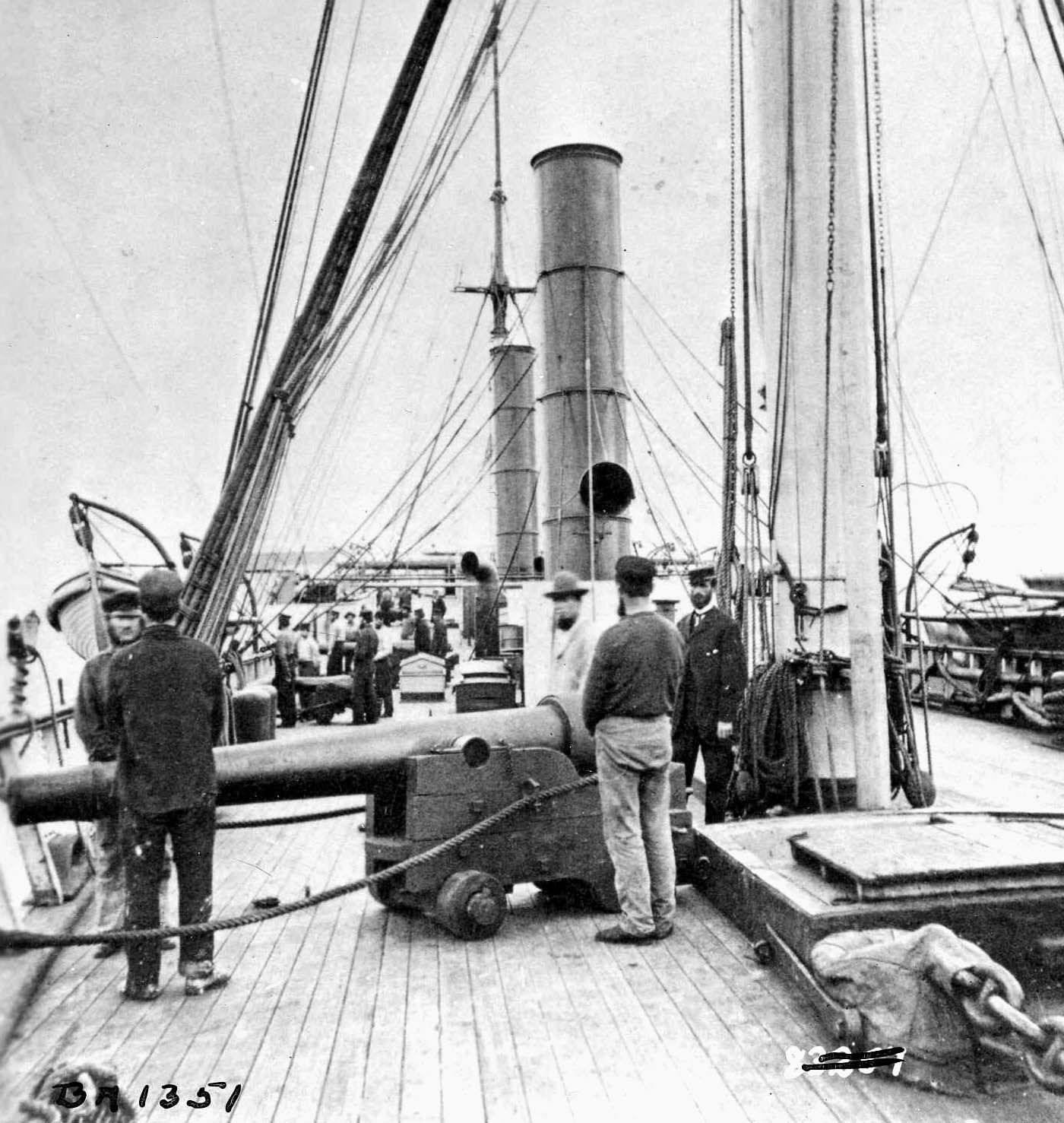

The photograph by Matthew Brady is of the gunboat U.S.S. Commodore Perry, a 143 foot long gunboat that was part of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. She mounted a number of cannon, including three 9″ (bore diameter) Dahlgren iron smoothbores (one shown on the left side of photo) and one 6.4″ (bore diameter) 100-pounder (weight of projectile) Parrott rifle (right side of photo). The boat served until the end of the war.