By Robert Barr Smith

On June 22, 1940, the British prime minister, the formidable Winston Churchill, directed that an airborne force of at least 5,000 men was to be formed. It was a noble notion but replete with difficulties, not the least of which were the absence of any doctrine, a lack of aircraft, and no organized training facility. The third problem was solved by setting up the “Central Landing Establishment,” a vague enough title to protect its function from speculation by the inquisitive. It resulted in some curious mail being sent to men assigned there, including letters addressed to the “Central Laundry” and the “Central Sunday School.”

[text_ad]

The absence of any doctrine existed because airborne assault was a very new thing in the British Army. Everything had to be improvised: buildings, training facilities, and, not least of all, aircraft. Some training jumps could be made from balloons, and they were. Other stopgap devices included a weird conversion of the aging Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley bomber, in which its rear turret was removed and the jumpers were launched into space from a little platform jury-rigged there. There was also a version of the Whitley with a hole cut in the floor of the fuselage, through which men dropped one at a time.

Later the paras would make civilized jumps through the doors of the omnipresent DC-3—the Dakota, to the British—but it would take time for overstretched production lines to produce enough of these versatile aircraft. The men were all volunteers, though; their leaders and trainers were tough, smart, and inventive; and the school progressed. And in time airborne soldiers would wear the distinctive maroon beret. Later in the war, some Germans called them the Red Devils, and the name was well deserved. They were also distinguished by the shoulder patch of the fabulous hero Bellerophon riding Pegasus into battle, an artistic touch said to have been the work of Daphne du Maurier, wife of Lt. Gen. Sir Frederick Arthur Montague Browning, nicknamed “Boy Browning,” who would command the whole airborne establishment.

The beret was distinctive, not only to ladies in pubs, but also to the enemy. A German friend of the author served throughout World War II. Recuperating from a wound, he took command of a scratch unit of old men and boys in what was supposed to be a quiet sector near the Dutch town of Arnhem. On the night of the British drop, one of his few veteran sergeants brought in a teenage machine-gun crew, crying bitterly, “They took our machine gun.”

My friend assumed it had been a neighboring unit, but the boys said, “They were big men in red berets.” A British patrol had seen the youth of the crew, taken the gun, and left the boys alone. “I knew then,” said my friend, “if I had any doubt remaining, that the war was surely over.”

Birth of the Glider Concept

The abiding problems in the early days remained, however. First, how to get the maximum number of troops on the ground before the defenders could adequately react, and, second, how to provide them with heavy weapons such as artillery, antiaircraft weapons, transport, and engineer equipment once they got to, or close to, their landing zone. Today’s heavy-drop technique was far in the future, and in any case there were no aircraft designed to deliver a howitzer or a bulldozer from the air.

A soldier could jump with his personal weapon, but getting heavy machine guns and mortars on the ground was a problem; so was enough ammunition for them. The initial answer was to drop such equipment separately in containers to be opened by the troops once on the ground. That was all very well if you could find the things in strange country, in the dark, with people shooting at you. That problem was partially solved by saddling jumpers with a separate bag much like a similar device used by the American airborne. Once out of the airplane you unhooked the device from your harness, and the bag then dangled below you on a length of line. The bag hit the ground first, taking the weight off the jumper. It worked, although those of us who have jumped so burdened did not enjoy the experience.

The answer to both problems was the glider, not only for resupply of weapons, equipment, and ammunition, but as a means to get a lot of people on the ground quickly and together, fully equipped and ready to fight. Once loose from the tug, you could land a glider in a pasture, a field of wheat, even a marsh, in theory at least. There was no landing gear to worry about; you could jettison the tricycle undercarriage at need and land the glider on its belly, some rudimentary skids taking up some of the shock, again in theory. You could build them as big as a tug aircraft could tow them, even building in a knock-away nose or tail so you could get big loads out quickly. You could tow one—later several—from a powered aircraft flown by a trained pilot.

The Glider Pilot Regiment

But gliders presented more serious problems of their own. First there were not any military gliders in Britain when the war broke out, nothing more than small, lightweight civilian sailplanes. Gliders were not the major problem. Those could be built, and the first order to British industry was for 400.

The second problem was more perplexing. Who would fly the gliders? In those early days the British armed forces were short of everything, and that included pilots. The Royal Air Force, engaged in driving off the Luftwaffe in the summer of 1940 and in creating a substantial bomber force to strike back, needed every one of its flyers. The obvious answer was to train soldiers to fly the glider force. After all, speaking pragmatically, they would not have to fly very far once the powered tug cut them loose in line with the target.

The British pondered the problem and opened training. The idea, which proved itself in practice, was that it was a great waste of a good soldier if all the two pilots did was land this glider contraption. They ought to be able to fight, along with their passengers, once on the ground. And so the Glider Pilot Regiment was born. It had only a brief lifespan. Born in 1942, it was disbanded in 1957, but during its life it covered itself with honor.

Hotspur, Hadrian, Horsa, and Hamilcar

The pilots were introduced to the first purpose-built military glider. It had an 88-foot wingspan and was called Hotspur, named in traditional British style for a North British fighting man. The little Hotspur would carry six infantrymen and their gear. Later on, some of the British airborne troops would ride to battle in the American Waco glider. The British called this one Hadrian, and it could lift 15 troops including the two pilots.

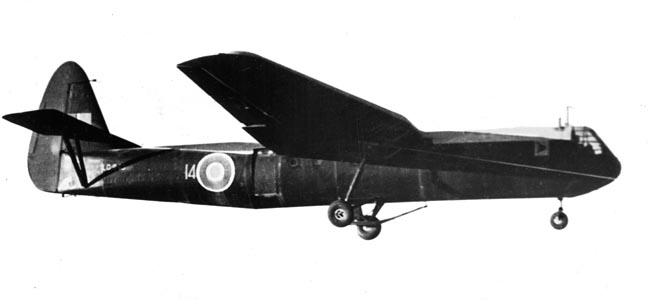

The Hotspur would be followed by the Horsa, namesake of a ferocious and successful Saxon warrior. To save weight, the skin of the Horsa, like that of the Hotspur, was plywood over a wooden frame. You could open the Horsa’s tail to get heavy gear out; you could even blow the tail off with what was called a “dynamite cartridge,” although that procedure involved some risk of setting the wooden airplane on fire. Later on, the air-landing units would get the Hamilcar, an 18-ton behemoth of wood over a steel frame, curiously named for a Carthaginian soldier.

There were two pilots up front, flying with standard controls. There was no throttle, of course; instead, there was a little red handle that released the 350-foot tow rope whenever the pilots deemed the moment propitious to land. A telephone line along the tow rope kept them in touch with the crew of the tug.

Later a curious instrument called the cable angle indicator was added. This device—irreverently called by glider pilots the “angle of dangle”—told a pilot flying at night his position in relation to the tug, either just above or just below the airplane up front. The glider pilots learned never to fly directly behind the tug, for the slipstream there could be violent enough to tear the fragile glider apart.

The Horsa was designed primarily to carry infantry. The larger Hamilcar was designed to carry a couple of jeeps with trailers, two Bren-gun carriers, or even a small light tank called the Tetrarch. The whole nose of the Hamilcar was hinged, so you could swing it up to roll out your load.

Finding Tug Crews

The whole project began modestly when, in October 1940, a pair of small aircraft towed two single-seat sailplanes. It would have been hard then to visualize what would come of this tiny experiment. The pilot school formally opened in January 1942, and the candidates trained not only in flying but heavily in combat skills as well. It was well they did. For example, a formidable sergeant pilot named Ainsworth landed in the water short of land off Sicily, swam ashore towing a wounded man, killed two Germans with a knife, disarmed still another one, captured 21 prisoners, and then fought on as infantry for several days more. Other pilots manned antitank guns and machine guns on the ground, some for days after landing.

There was never a shortage of able, willing volunteers for the airborne forces, but tugs were another matter. RAF bomber crews were as scarce as trained fighter pilots, and only a few could be spared at the start. The same went for the aircraft at first. Most of the aircraft big enough to haul a glider were bombers, some already becoming obsolete. Among them were the Handley Page Halifax, the Armstrong-Whitworth Albemarle, and the ungainly Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley, considered so behind the times that it was pulled out of production in 1941. The workhorse of the Allied airborne in future years, the Douglas C-47, was still coming off the production lines in the United States. It would be produced in prodigious numbers but was needed in large quantities all over the world. The new airborne division was just one customer.

Even as the tug fleet increased, the crews were also permitted to fly combat sorties into occupied France, generally low-level attacks on transformer stations to disrupt the power grid. They also dropped supplies to the French Resistance and British agents operating with them. Such missions were more than morale builders; they also provided what was quaintly called “flak inoculation,” getting the crews used to pressing home their attacks in a sky full of tracers, precisely what they would be called upon to do when they towed gliders into action.

In spite of a lack of doctrine and shortages of equipment, the training went on, with more and more gliders becoming available and RAF crews ordered into the towing operation. More and more airplanes became available, and a little later in the war American C-47 crews would also carry British airborne soldiers into battle. Regular infantry battalions would be assigned to what were now being called the air landing brigades.

Training From Trial and Error

In October 1941, Maj. Gen. Boy Browning left the Guards Brigade to become commander, paratroops and airborne troops. The airborne division he was to command was nowhere near full staffing and organization and was short of almost everything, but one of its major elements, 1st (Air Landing) Brigade, was quickly assembled.

The brigade was composed of a battalion each of the Border Regiment, the Ox and Bucks Light Infantry, the Ulster Rifles, and the South Staffordshire Regiment. These were all storied infantry units, all loaded with battle honors from a dozen wars. To them the British added a recon company, an antitank battery, a “field ambulance” of medical personnel, and small support units. As the airborne forces expanded, other infantry battalions and artillery batteries were added. The brigade trained separately from the paratroops, who were drawn from volunteers all over the Army, and would become the 1st Parachute Brigade.

By the summer of 1943, there would be three parachute brigades in addition to the air-landing outfits. Their support included light artillery units equipped with American 75mm howitzers, and they would be moved by large numbers of Dakotas, many flown by American pilots. But that was well into the future. For now the paratroop and glider pilot training cadres made it up as they went along.

The division’s leaders were able and hard-driving commanders; one particularly tough battalion commander was nicknamed “Dracula” by his soldiers. Physical conditioning was high on Dracula’s list of desirable things, as it was throughout the regiment. The pilots were famous for their discipline and military bearing. They were coming to be recognized as the elite soldiers they were.

Since there was virtually no experience to draw from, all was improvisation and trial and error, down to experimentation and modification of parachutes, uniforms, weapons, harnesses, and kit bags. Training was improvised too, but the command of the new airborne forces settled on two jumps from a captive balloon and five from aircraft, including a night jump. Ringway, the training installation, also hosted foreign volunteers, especially Polish soldiers, and gave a special short course for several thousand SOE (Special Operations Executive) agents—including a number of women—for their night drops into occupied France.

The glider pilots trained with the Royal Air Force at Derby and went through the same 12-14 week course in powered aircraft as did the RAF pilots, flying the forgiving Tiger Moth. After glider training—both day and night flying—some were selected for the big Hamilcars; the rest would fly the Horsas, the troop carriers leading the attack. With everything in short supply, some of the lighter gliders were towed in training by antique Hawker biplanes.

Specialists of the Airborne

Medical support for both air-landing troops and paratroopers was provided by the field ambulances, which landed with the men they supported, both paratroops and glider soldiers. One doctor, an officer named Robb, performed more then 160 surgeries during the North African fighting. Most of his operations were major, and he lost only a single patient. His last patient was himself, for he had injured one knee on landing; he had said nothing and had hobbled on until his job was done. Hippocrates would have been proud. He and other airborne doctors were supplied by air after the initial landings, blood plasma and surgical gear dropped in weapons containers.

The air-landing brigades included a full company of Royal Engineers—the parachute brigades each had a platoon—signal detachments, small headquarters elements, and light artillery. Horsas carried the gunners and their howitzers. One glider could lift six passengers, a gun, a jeep, a trailer or two, and perhaps a motorcycle. Supplies and ammunition arrived not only by glider but were dropped in simple wicker panniers, carrying up to 500 pounds, pushed from an aircraft door from a conveyor system. Weapons were also dropped in what the British called bombcells, metal containers that fit the bomb racks on fighting aircraft.

These and many other vital things trickled down only slowly to the troops, from a supply system overwhelmed with the immense requirements of all the Allied forces. The airborne forces had settled on the American jeep as the ideal transport for troops on the ground. But by early 1943, this vital vehicle was still in short supply. At one point, 132 of them were reported to be “standing on the quayside waiting to be delivered.” But, as one British soldier recorded, “It could not be discovered on which side of the Atlantic this quayside was.” There were shortages too of 20mm cannon, of 6-pounder antitank guns, and a dozen other things the troops required. But the men—the cream of the crop—were ready.

A handful served in an indispensable unit that played a crucial role in glider operations. Called the Independent Parachute Company, they were pathfinders, dropped in ahead of the parachute troops and gliders. First into any LZ (landing zone), they deployed a signaling device code-named Eureka, which broadcast to an aircraft-borne receiver called Rebecca. They could set up lights as well, when and if the tactical situation permitted.

Disaster in Operation Freshman

The first airborne operations were small ones, the first a strike against a major aqueduct in southern Italy. The insertion was by parachute for this one, a small element that succeeded in blowing a span out of the aqueduct and dropping a bridge. But none of the raiders made it out to the coast where they were slated to be collected by submarine, which in any event could not itself keep the rendezvous. The second airborne raid, however, was a tremendous success.

This time the airborne troops dropped on the French mainland, where they attacked a German radar station at Bruneval, on the coast. The objective was parts from the big Würzburg radar, which British boffins needed to devise countermeasures. While the soldiers shot up the German garrison, a Royal Air Force NCO named Cox calmly dismantled the apparatus, and took what he needed. The Royal Navy lifted the raiders over the beach, complete with radar parts, and British casualties were minimal.

But the gliders had still to be tried. Their first test was a small one, Operation Freshman, in November 1942. Two Horsas, carrying sappers, were towed from Scotland to Norway, a mission of some 400 miles. The objective was the Norsk Hydro heavy water plant about 60 miles from Oslo. The mission was fraught with peril because navigation was extremely difficult and the weather bad.

One tug, flying beneath cloud cover to locate the objective, smashed into a mountain. The crew all died, but the glider was jarred loose. It landed heavily, killing or injuring several more sappers. The second tug flew higher, but as it crossed the Norwegian coast, turbulence jerked the glider loose. It landed near the wreckage of the first, and the Germans quickly rounded up the survivors. The Gestapo took jurisdiction over them, and they were eventually murdered—shot or strangled pursuant to Hitler’s notorious “commando order.”

Taking Ponte Grande Bridge

In the spring of 1941, the dramatic German parachute and glider attack on Crete painted a spectacular picture of what airborne soldiers could do: with massive close air support, a fleet of transport and tug aircraft, and a sky full of gliders, the Germans carried the island. But Crete also emphasized the risks attendant on attack from the sky against fierce opposition. While Crete fell, the island was also the grave of the German airborne. Those who did not die on Crete kept their pride and morale, but they fought as regular infantry through the rest of the war.

Not so the British. The British airborne forces would persevere. After the fighting in North Africa—most of which involved neither parachutes nor gliders—the first major effort for the air landing units would be Sicily. Lots of hard lessons were learned there, by both the British airborne and the American 82nd Airborne Division. General Jim Gavin of the 82nd Airborne aptly described the operation as a “self-adjusting foul-up.” Even so, much was learned and much accomplished, in particular the capture of two vital bridges by the British—at Primasole and Ponte Grande.

Just getting there was a major undertaking. The gliders first had to be flown from Britain to the new Allied bases in North Africa. The task required the Halifax towing aircraft to fly a total of about 70 hours per mission. Some 50 of these were spent towing the vital gliders. Worse, their route to their first stop, an airfield near Casablanca, took them far too close to German territory, and they flew crammed with extra fuel. At least one tug was shot down by Focke-Wulf Fw-200 Kondors. Its glider landed in the sea, and its pilots were collected several days afterward by a passing Spanish ship. In about the same area another pair—both tug and tow—simply disappeared without a trace.

The glider-borne troops this time flew mostly in Wacos with British pilots, hastily trained in this unfamiliar aircraft. Some of the pilots even assembled their own gliders—at one airfield glider pilots put together 52 gliders in just 10 days. And the operation was indeed a series of errors from which everybody learned. The weather was foul, with a gale-force wind that made it difficult for the tugs and gliders to stay on course. The trip was especially difficult for the glider pilots trying to keep station with their tugs. It was about 450 miles long, and the aircraft flew at no more than 100 feet. The completion of the mission speaks volumes for the endurance and expertise of the glider pilots.

Their landmarks invisible in the gloom of the night and shrouded in a monstrous dust cloud driven by a powerful offshore wind, many of the gliders dropped their tows too soon and ended in the ocean. Clinging to the remains of their glider, Brigadier Philip Hicks, commanding the air-landing brigade, spoke drily to his brigade-major. “All is not well, Bill,” he said, and it was a massive understatement. Only 52 gliders managed to reach the land, and only 14 landed anywhere near their target LZs.

Even so, the Ponte Grande Bridge fell to a Lieutenant Withers and some 14 men of the glider-landed South Staffords. Withers and five of his men swam the canal, and his minute force then put in its attack from both ends of the bridge. This handful of glider soldiers removed the enemy’s demolition charges and with occasional small reinforcements held doggedly onto the bridge through the night, although there were never more than 100 troopers to fight off determined counterattacks. Driven off the bridge at last, the glider troops met other friendly units advancing and took the bridge back. It was now permanently British.

The Second Wave Lands

In the blackness over Sicily, German antiaircraft fire hit one Horsa, unfortunately carrying bangalore torpedoes; it exploded in the air. Three other Horsas flying with it, however, put down safely. Finding themselves some 25 miles from their objective, the soldiers on board nevertheless, as the British put it, “yomped” through the night and got their mission done. A handful from another crashed glider—just six men of the South Staffords, including a doctor—rejoined their unit after swimming ashore, crawling under a 20-foot tangle of barbed wire, and marching 10 more miles in the darkness. Along the way they accounted for an antitank gun, three machine guns, and a couple of pillboxes, and brought in 21 prisoners.

Wherever they found themselves, the glider troops raised havoc with whatever hostile units they encountered, although much of their time was spent wandering through the gloom of a strange landscape, searching for each other and for somebody to fight. One small group from brigade headquarters, including the brigade commander and a handful of glider pilots, put in their own improvised attack on a shore battery, working through the enemy wire and destroying five field guns and the ammunition dump.

If the initial landings had been bad, worse was to come. As a second wave of powered aircraft and gliders approached the coast, gunners on the Allied invasion fleet, cruising off the Sicilian coast, mistook the transport aircraft and the gliders for hostile aircraft and opened fire. Casualties were heavy as aircraft were destroyed in the air or crashed into the sea. The final casualty list counted 50 gliders crashed at sea out of a force of 108; another 25 had simply disappeared forever.

Nevertheless, the glider soldiers and their pilots had acquitted themselves very well indeed. Although they could not know it yet, there was a monumental test waiting for them, one on which the future of the world quite literally depended. Back in Britain planning was already well advanced for Operation Overlord, the invasion of Festung Europa from both the sea and the sky. Overlord would be the payoff for all the years of training, the casualties, the disappointments, and the valor. Of all the extraordinary feats of arms in this or any other war, the glider assault on the French mainland has few equals.

The Gliders of Operation Overlord

Deep in the night of June 5, 1944, flights of gliders crossed the English Channel for one of the most crucial assaults of the war. The crossings of the Orne and Caen Canals were vital to the Normandy invasion, and these gliders were headed for those objectives. As the vast invasion fleet set to sea from England and thousands of British and American paratroops headed for the French shore, the glider pilots headed through the night to find their objectives in the darkness.

The chief worry of the Allied planners was the German panzer formations held well behind the beaches. While some of the German units manning the beach defenses were of less than the highest quality, three divisions in reserve were first class, including the 12th SS Hitler Jugend Division with its Panther tanks. The veteran 21st Panzer Division was also equipped with Panthers, and the 352nd Infantry division was at full strength as well. Among them, these three divisions boasted some 60,000 men in addition to the first-line tanks. A massive armored counterattack into the flank of the British at Sword Beach could mean disaster for the whole invasion force.

To hold up any German assault, the bridges had to be captured and held. This task, on which so much depended, went to 6th Air Landing Brigade and to three platoons of the 2nd battalion, Ox and Bucks Light Infantry, with an attached detachment of sappers. The success of their mission hung on their ability to quickly take and hold the bridges. That in turn depended on six Horsa gliders and their Army pilots, one of whom was the redoubtable sergeant-pilot Ainsworth, the single-handed scourge of the enemy in Sicily.

The gliders had to be landed close to the bridges so that their infantry could strike the objective before the Germans had time to react in force. That depended on the skill of the pilots, and they did their job nearly to perfection. Three gliders headed for each of the bridges. One missed its landmarks and landed several miles away from the objective. The others, however, released from their tugs just as they crossed the French coastline, landed almost on top of their targets, one coming to earth less than 50 yards away from the Caen Canal bridge.

That glider landed so close to the target that its nose pushed into the German barbed wire and the canal embankment. Ainsworth and his colleague, Sergeant Wallwork, were thrown through the windshield with the shock of the landing. He was the first Allied soldier, said Walwork later, to land in occupied Europe.

It was remarkable flying.

The remaining two gliders assigned to the Orne bridge also landed close to the objective. The infantry swarmed out of their gliders and shot their way across quickly. “Ham and Jam,” radioed the commander of the bridge assault; it was the signal of success, anxiously awaited by the rest of the British command. The captors of the bridges were soon reinforced by other division units, and the British would hold the vital bridges firmly while the invasion force came ashore. The vital flank of Sword Beach—and the rest of the invasion forces—was secure.

The Caen Canal bridge was renamed “Pegasus Bridge” after the war, and it carries that proud name today. The Orne bridge is called Horsa bridge, honoring the pilots who put their passengers so close to the objective.

90 Gliders on Normandy

More than 90 other gliders dropped out of the night sky onto French soil, most of them carrying antitank weapons, and many of these were scattered across Normandy. The pilots of one, looking for anybody friendly, stumbled into German fire and went down wounded. One, Sergeant Jock Bramah, was shot through the lung and left for dead. He managed to find shelter in a nearby village. Ten days later, as German troops came to capture him, Bramah shot two of them, jumped out a window, and vanished into the night. Like Ainsworth, he fit the mold of the Glider Pilot Regiment exactly.

Gliders also helped out in the paratroop attack on the vital Merville Battery, which enfiladed Sword Beach. The plan called for three gliders to land virtually on the battery, inside the protective wire entanglement, while the paratroops attacked from outside the perimeter. Two gliders found their target, but both were hit on the way in. One finally landed two miles away. The pilot of the other, coming in to land, at the last moment spotted a mine-warning sign on his chosen LZ and managed to pull up the glider, leapfrog the mines, and crashland in an orchard beyond the minefield. His passengers piled out and immediately ran into German troops hurrying toward the battery. The glider soldiers fought the Germans off, and the paratroopers carried the battery and spiked its guns.

Overlord complete, and the Allies firmly in control in Normandy, glider pilots next flew in Operation Dingson, the successful delivery by 11 Horsas of French SAS men, their jeeps, and their machine guns on their way to join the French Resistance. Their job completed, the British crews were passed through the American lines and on back to Britain.

Glider Assaults After D-Day: Market-Garden and Beyond

Market-Garden, the famous “bridge too far,” in Boy Browning’s words, left the Glider Pilot Regiment with terrible losses. Of the more than 1,300 pilots who landed in Holland, 229 were killed and almost double that number wounded or captured. The commander of the British 1st Airborne Division wrote that the glider pilots “played all kinds of parts but everything they were asked to do they did wholeheartedly.” In typically dry, understated British military prose, it was the highest possible compliment.

One of the wounded, Lieutenant Michael Dauncey, led two paras in a rush that captured eight German prisoners and a machine gun. Taking a piece of shrapnel in the eye, he went to the dressing station, which could not help him. Dauncey consoled himself by sleeping awhile and next morning returning to the fighting. Shot again and his jaw broken in two places by a German grenade, Dauncey was captured.

After treatment in a Dutch hospital, Dauncey was moved to a German prison hospital. Still full of fight, he and a Black Watch officer shinnied down a rope of knotted sheets, climbed a barbed wire fence, and disappeared into the night. They managed to find shelter with a civilian doctor and his family, and by February they were back in the British lines.

Three other, much smaller glider-borne operations took place in 1944. All were daylight landings. In the first, in February, three Hadrians carried a military mission to Tito in what was then Yugoslavia. The operation was called Bunghole; its vaguely obscene title may have had something to do with the fact that the passengers were Russians. After a successful landing in snow, the pilots remained with the partisans for several weeks until the RAF could get a Dakota on the ground to lift them out.

Thirty-five Horsas were part of Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France in August. Again the mission was a complete success, the airborne forces holding until the amphibious landing forces reached them. Another success was Operation Manna, 40 Hadrians landing near Megara, Greece, to help in the liberation of Athens. Four of them carried bulldozers, the rest of them troops and jeeps.

Crossing the Rhine With Operation Varsity

In spite of the losses of Market-Garden, the Glider Pilot Regiment was ready and willing when the time came for the crossing of the Rhine, Operation Varsity, in late March 1945. The pilots’ depleted ranks were filled out with some 1,500 Royal Air Force pilots, trained in a conversion course to fly gliders. Once more, casualties were heavy; 60 percent of those killed, wounded, or missing were men of the RAF.

Casualties were heavy in the infantry as well. Many men of the 2nd Battalion, Ox and Bucks Light Infantry, died in the air as German flak tore into their gliders. One soldier later described the chaos of the assault: “With some of the controls damaged and no compressed air to operate the flaps, we flew across the landing zone … to crash head on into a wood … number 1 glider … was breaking up, spilling out men and equipment as we had done—except that with them there were no survivors….”

This single battalion took more than 100 casualties in dead alone, and the LZ was littered with the wreckage of gliders shattered and burning. Its fighting strength was reduced to about 200 men, and much of their equipment had not survived the landing. But they held onto their objective—a bridge across the river Issel—until German tanks backed by infantry grew too strong and too numerous. The panzers’ armor was simply too thick for the few 6-pounder antitank guns that had survived the carnage among the gliders. What was left of the battalion blew the bridge and fell back.

Other air-landing battalions had similar experiences trying to fight off armor with their few lightweight antitank guns and PIATs, the spring-loaded, short-range cousin to the German Panzerfaust. But the aggressive British infantry held on, knocking out individual German strongpoints with grenades and Sten guns. The flak positions were silenced, clearing the way for more landings.

And there was help from the Royal Artillery as well. Two 25-pounder howitzers survived the landing and went into action, hitting German positions with smoke rounds, marking them for the “cab rank” of cannon-armed RAF Hawker Typhoons orbiting over the battlefield and waiting for targets. Heavy British artillery fire from across the Rhine added to the strength of the surviving infantry. A little more support came from men of the Armored Recon Battalion. Only two of their little tanks—Locust, they were called, successor to the Tetrarch—made it to the ground unscathed, but they went into action immediately.

For all the casualties and confusion, the air-landing troops had done their job. The glider troops carried all their objectives and within a day had linked up with 21st Army Group.

End of Glider Infantry

The regiment is only history now, and most of its pilots have passed on. But the memory remains—a luminous memory—of tough and gallant men who flew unarmored, unpowered aircraft, fragile and vulnerable, into the teeth of streams of tracers and the deepest gloom of night. Often without landmarks, buffeted by winds, they managed to land their troops on or near their objectives with astonishing frequency. Like Sergeant Wallwork, crashing through his windshield to be the first invader of Europe, like the paras they flew at the point of the spear … and drove it home.

My dad was a pattern maker and worked on making gliders in WW2. He was stationed in Nailsworth and I think he worked in Stroud. Is it possible to tell me the company where he may have worked? He was there until the end of the war.

Thank you