By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

Beneath the Gothic steeples of their churches, the priests of Wallachia prayed that the Austrians would deliver them from the Turkish yoke. The cold winter winds howled outside the massive stone walls. Imperial raiders galloped through the white countryside of Wallachia, Bosnia, and Serbia. Although major hostilities had ceased for the winter, the war between Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI and Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III continued to drag on.

[text_ad]

Far to the west, across the frozen Hungarian plain to the crags of the Alps, the city of Vienna, hub of the Habsburg Empire, nestled between the Danube and Vienna Rivers. Nobles feasted and waltzed in gold-and-white marbled palaces, celebrating the year’s victories of their champion, Field Marshal Prince Eugene of Savoy. A year earlier, Eugene had defeated the Turks at Peterwardein, the “Gibraltar of Hungary,” and then proceeded to wrest control of Temesvár, the last Turkish stronghold north of the Danube. The 53-year-old prince was not only the Holy Roman Empire’s most celebrated warrior, but also one of the great captains of his age.

Sparking War With the Ottomans

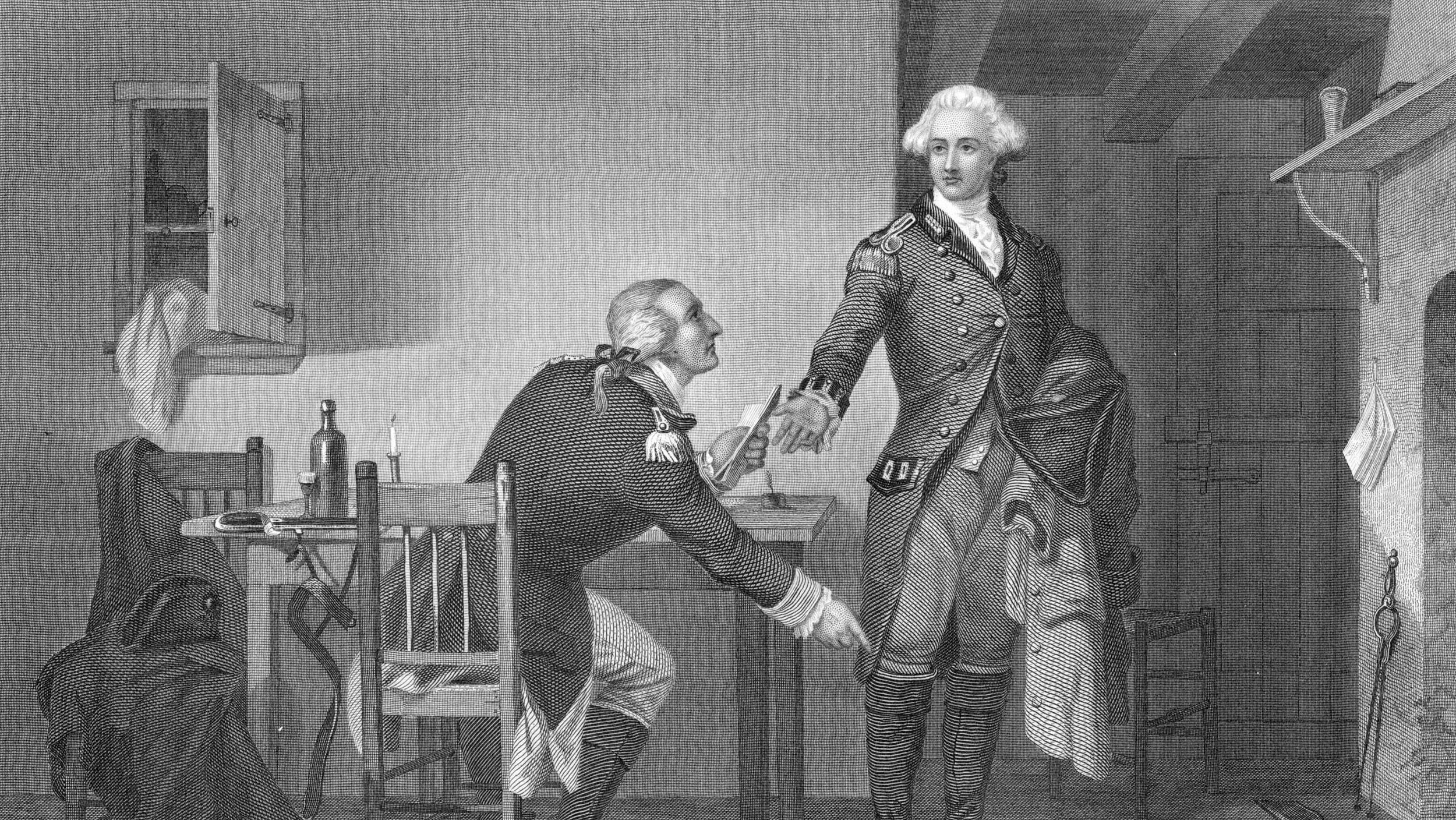

Eugene was of Italian heritage but grew up in France. When he came of age, his king, Louis XIV, refused him a military career, sizing up Eugene as a short, frail dandy whose scandalous mother was infamous for her affairs and dabbling in magic. Undaunted, Eugene defected to the Austrians just in time to battle the Turks investing Vienna in 1683. The battle awakened Eugene’s warrior heart and changed his life.

During the Second Turkish War (1683-1699), the Nine Years’ War (1689-1697), and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), Eugene won military laurels through his personal bravery and his tactical and strategic genius. His adoring soldiers nicknamed him their “brown Capuchin” after the plain brown coat he preferred over a more lavish officer’s uniform. Eugene’s masterpiece was his 1697 victory over the Turks at Zenta, which ended the Second Turkish War with the Peace of Karlowitz and made Eugene a European hero and Austria a major European power. A shrewd statesman and patron of European culture, Eugene became the right-hand man of Emperor Joseph I and his successor, Charles VI.

Both Eugene and the Porte, the Ottoman high command, regarded the Peace of Karlowitz as little more than an armistice. In 1711 the Turks were back, defeating Czar Peter the Great’s Russians on the River Pruth. Four years later, eager to regain what was once theirs, a Turkish army swamped the meager forces of the Venetian kingdom of Morea. The locals, who had smarted under injustices done by Venetian nobles and Greek pirates, hailed the Turks as liberators. After a 100-day siege, Morea was Turkish once more, leaving the Turks free to turn on Corfu.

Both Russia and Venice had been Austria’s allies in the Second Turkish War. To Eugene, it was obvious that the Empire would be the Ottomans next target. He believed it was better to go to war sooner rather than later because a rare spell of peace in Western Europe freed the imperial army to concentrate on the Turks. At the urging of both Eugene and Pope Clement XI, Charles VI insisted that the Ottomans relinquish their Venetian conquests. The Porte replied with a declaration of war in 1716, but after Eugene’s victories at Peterwardein and Temesvár the Turks decided it was wiser to cease hostilities. They lifted the siege of Corfu and pleaded for an armistice.

The Turks found support among the English, who wished to curtail Austrian power and see Temesvár returned to the Turks. On the other hand, Peter the Great, who was eager to avenge his earlier defeat, offered to join the war against the Turks. Eugene would have none of it; Emperor Charles VI heeded his advice. The war would continue without the Russians. There was no need to let Russia have easy land grabs in the Danube region while the Turks slugged it out with the Austrians. The Empire did accept much-needed financial aid from Prince Maximilian of Hesse, Elector Max Emmanuel of Bavaria, the Venetian Signoria, and the pope, who imposed a tax on the clergy of Naples, Milan, and Mantua to help fight the Turks. Half a million additional guldens were extorted from the Jewish community.

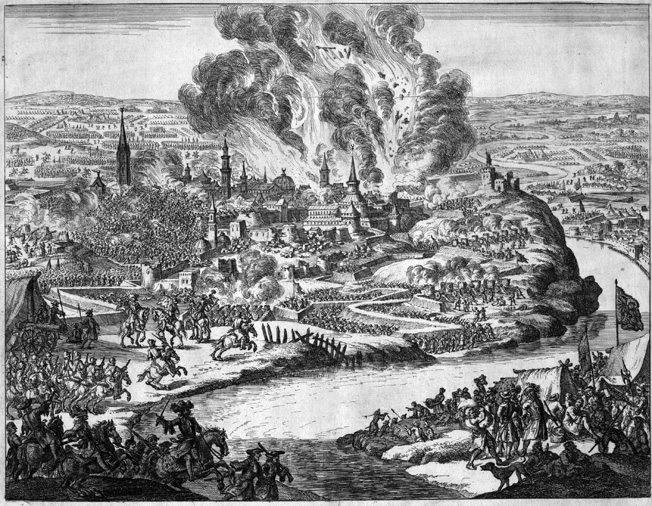

Belgrade: “House of the Holy War”

Eugene wished to deal the Turks a crippling blow before new fighting broke out in the west. His thoughts centered on the southeast, on the prize that had so far eluded him: Belgrade, the Turks’ “House of the Holy War.” The strategic fortress-city was the gateway of the Turkish invasion route into central Europe. It was also a major trade center and the capital of Serbia. The capture of Belgrade would force the Turks to their knees.

Belgrade had seen four bloody battles in the last 30 years. Elector Max Emmanuel of Bavaria seized it in 1688 after 26 days of siege. Eugene himself was there that day, fighting side by side with the elector. Through enemy fire, the young Eugene led his troopers up to the walls of Belgrade, where a musket ball shattered his knee. Eugene’s wound took months to heal and was complicated by a severe onset of bronchitis and sinusitis. The victory proved short-lived in any event, as Mustafa Kuprili recaptured the city in 1690. Three years later, a 49-day Austrian siege was unable to force the garrison into submission, leaving Belgrade solidly in Turkish hands.

Planning to Draw Out the Turks

In 1717, it was Eugene’s turn to try and hoist the imperial banners over the walls of Belgrade. In preparation for the campaign, he raised additional heavy artillery and magazines and augmented the Danube fleet with 10 new warships. The bigger ships boasted 1,000 men and 56 guns. On May 13, the boom of Vienna’s cannons heralded the birth of Maria Theresa, the future empress and daughter of Charles VI and Empress Elisabeth Christine. Eugene had delayed his departure for the eminent event. When Eugene left Vienna the next day, Charles VI presented him with a jeweled cross. Aware of Eugene’s reckless nature, the emperor warned Eugene to take care of himself.

Eugene sailed down the Danube, disembarking at Buda. Eugene stayed just long enough to attend Mass and inspect the fortifications and the supply depot before continuing on to Futak, west of Peterwardein, on May 21. The Hungarian village would serve as the assembly point of Eugene’s field army.

Eugene had increased his field army by 20,000 men, 17,500 of whom were raised in Hungary, the rest in Italy. At 100,000 men strong, supported by 200 guns and the Danube flotilla, it was the largest army Eugene had ever led against the Turks. Eight thousand volunteers, including nobles from half the royal houses of Europe, came to fight at Eugene’s side. There were 45 nobles from Germany and France alone, including two princes from Lorraine and a company of Frenchmen led by the grandson of the late Louis XIV. The largest volunteer contingent was that of General Field Marshal Alexander Maffei, another veteran of the 1688 siege of Belgrade. Maffei brought with him the two sons of Elector Max Emmanuel of Bavaria and 5,700 stalwart Bavarians. Also in Eugene’s army was 20-year-old Herman Maurice, the Comte de Saxe, who had served under Eugene since the age of 13. What he learned from Eugene would help Saxe become France’s premier soldier.

Although Eugene knew very little about the size and status of the Turkish army, he planned to draw it into battle by laying siege to Belgrade. Wishing to gain the initiative, Eugene did not bother to wait for the last straggling troops to join his army. He had sent his favorite general, Count Florimund von Mercy, to scout ahead. Using Mercy’s information, Eugene left Futak on June 9 to march his army east along the north bank of the Danube. On June 15, he crossed the Danube at Pancsova. Eugene then doubled back west to approach Belgrade from the east and rear. His route allowed him to cross the Danube out of range of Belgrade’s artillery and to approach Belgrade from the base of the triangle formed by the confluence of the Rivers Danube and Sava, which flanked the city from the north and west.

While his army closed in on Belgrade, Eugene personally led a reconnaissance mission. It nearly cost him his life when 1,200 Turkish cavalry waylaid Eugene and his escort. One of the Turks leveled his pistol at Eugene and came within a hair’s breadth of pulling the trigger before an imperial bullet struck him down.

Choosing not to risk an immediate assault, Eugene planned to enclose the city within a ring of entrenchments. They were designed not only to guard against an outbreak from Belgrade but also to cover the rear of the imperial army in the event of the arrival of a Turkish relief army. Eugene’s siege lines ran in a semicircle from the Danube to the Sava, enclosing Belgrade from the landward side. In addition, his men built a pontoon bridge over the Danube and another over the Sava to allow easy access into Hungary.

Lieutenant Field Marshal Count von Hauben established a bridgehead on the western bank of the Sava, driving the Turks from the higher ground at Semlin and entrenching himself with 16 battalions of infantry, 17 cavalry, and assorted Bavarian units. From there he could bombard northern Belgrade and guard the supply and communication routes to Peterwardein.

Mustafa’s Assault With Cries of ‘Allah’

Belgrade’s defenses had been heavily upgraded since the last battle at the end of the century. Its able commander, Serasker Mustafa Pasha, held Belgrade with 30,000 men, among them the cream of the Janissaries. Six hundred guns were at Mustafa’s disposal and 70 ships guarded the river approach. Belgrade’s civilians had been cleared from the city.

Mustafa watched as cannon fire erupted from the parapets, blasting the imperials who were busily digging trenches in the marshy grounds bordering the rivers. Mustafa was ready to fight until the Turkish relief army arrived. In small boats and raiding parties, the Turks harried imperial efforts to finish the siege lines. Janissary Serdengecti, or “head-riskers,” left behind decapitated imperial corpses. A ducat was awarded for every Christian captured. Meanwhile, Turkish and imperial ships plowed the river, preying on each other’s supply transports.

On July 11, the imperialists captured Turkish outposts on the north bank of the Danube. Two days later, Mother Nature came to Mustafa’s aid when a terrible storm played havoc with the imperial camp. Winds whipped the waters into a frenzy, battering to pieces parts of the two bridges, pulling under supply ships and washing wagons and their hapless oxen into the river. A Turkish half-galley drifted into an imperial warship.

Seeing the imperial camp in shambles, Mustafa launched 10,000 men over the Sava. The Turks were out to finish off what remained of the mauled bridges and take the trenches. A Hessian captain held them off until reinforcements hurled back the enemy.

Four days later, with cries of “Allah,” the Turks launched another assault. This time they hit the unfinished trench lines near the Danube. Imperial officers in the area squabbled over whether to await the attackers or sally forth and meet them head-on. The situation became critical, but Eugene instantly counterattacked with 250 cuirassiers of Prince Philip von Hessen’s regiment. Sabers flashed as the cuirassiers, resplendent in their ridged helmets and bullet-tested breast and back plates, sent the Turks reeling.

Khalil’s Relief Force Bound For Belgrade

Mustafa’s efforts and a lack of available timber slowed down imperial efforts to dig more trenches and ravelins (triangular fortifications). Reinforcements continued to trickle in, along with heavy artillery shipped on river transports. By July 22, the siege lines were finally completed. Eugene’s artillery hammered Belgrade relentlessly. The iron balls of his long field guns blasted apart fortifications. Grapeshot and explosive bombs from howitzers shredded defenders. A lucky mortar shot struck an ammunition dump, blowing up several thousand Janissaries assembling for another raid.

But Eugene’s attrition of Belgrade’s defenders had started too late. By the end of the month, the news he dreaded arrived. He had hoped to have Belgrade in his hands before he confronted the Turkish army. It was not to be. Cavalry scouts returned to herald the imminent arrival of the enemy army. An intercepted Turkish letter written by the Grand Vizier Khalil Pasha himself flaunted a 300,000-man army. However, as Eugene no doubt guessed, Khalil’s boastful letter greatly exaggerated the strength of the Turkish army.

Khalil had his own problems getting his war machine into gear. In the wake of Eugene’s victories in the previous year, the Ottoman soldiers were demoralized. Many wandered away before reaching the traditional muster at Adrianople. They risked execution by strangling, the punishment for desertion, rather than face the imperials. Artillery losses had been so heavy that guns had to be shipped from far away Middle Eastern arsenals.

The only Turkish units worth their salt were those of the Janissary corps, the “slaves of the Sultan,” and Spahis, or professional Ottoman cavalry. These elite units made up only a fraction of Khalil’s immense army, which numbered around 160,000 men, including 80,000 cavalry and 120 guns and mortars. The rest of his soldiers were poorly armed and poorly trained rabble collected from the provinces—of little more military value than the tens of thousands of camp followers. The latter included the Ordu Esnaf, literally an army of artisans, who provided everything from blacksmiths and pharmacists to candle makers and sheep’s head sellers. The great number of noncombatants swelled the Turkish host to over 200,000.

In the Crossfire of the Turkish Guns

Much of Belgrade lay in smoldering ruins. Victory for the investing army seemed merely a matter of time. But the eyes of many soldiers in the trenches were on the battered battlements to their front, where the Turks erupted into inexplicable jubilation on July 28, shooting rockets and fireworks. The exhausted, walrus-mustached imperial troopers beheld the arrival of Turkish cavalry, with its horsetail banners and green and yellow-forked flags, on the slopes to their rear.

During the next few days, countless more Turks wandered in from the valley of the Morawa River, including Khalil Pasha himself. Khalil was not known as a great military commander, but as a former governor of Belgrade he had firsthand knowledge of the battlefield that lay before him. Accordingly, Khalil deployed his army in a half-moon position on the Heights of Crutza and Badjina south of Belgrade and Eugene’s siege lines, which were so deep and high that they resembled a fortress. Khalil decided against an assault. Instead, at the beginning of August he began bombarding the imperial forces squeezed between his army and the besieged city.

News soon spread throughout Europe that Eugene was trapped. The prince was aware of his dilemma but determined to hold out, hoping that Khalil would risk an assault on the imperial lines or be forced to withdraw due to lack of food. But Eugene had misjudged the situation. Two weeks after he arrived, the fire from Khalil’s guns was, if anything, getting more severe. Khalil had boldly advanced his own trench lines and batteries within musket range of the Imperial lines. Eugene’s bridge over the Sava was threatened. If it fell, the corps at Semlin would be isolated.

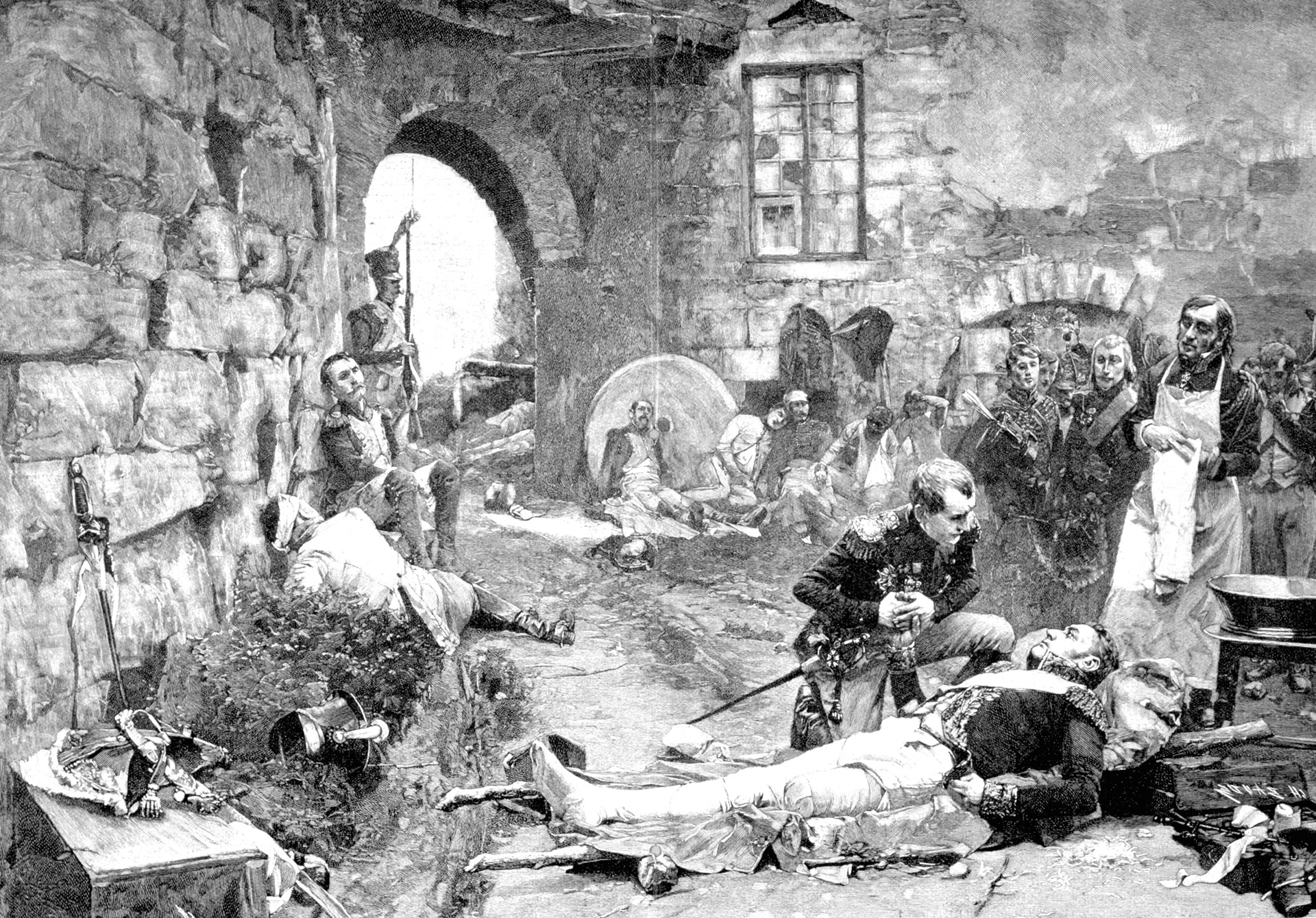

The imperial soldiers were caught in a murderous crossfire between the guns of Belgrade and those on the higher ground held by Khalil’s relief army. Casualties from the bombardment mounted, adding to those lost to exploding Turkish mines and infiltrating Serdengecti. Many imperial soldiers fell ill to dysentery augmented by an unbearable heat wave. Turkish galleys hindered transports from bringing in much-needed supplies. Attended by princes eager to learn the art of war, Eugene daily inspected his own lines and those of the enemy. He knew that his army was nearing the brink of collapse. There was no choice left for Eugene but to attack before his men completely withered away.

“Either I Will Take Belgrade, or the Turks Will Take Me”

At 3 pm on August 15, Eugene summoned his commanders for a council of war. With their complete support, he announced that he would attack the Turkish relief army. “Either I will take Belgrade, or the Turks will take me,” he joked grimly. He knew that victory at Belgrade, for either side, would spell the end of the war since neither the Emperor nor the Sultan could afford to raise another army.

As usual, Eugene planned the attack in the smallest details. Sixty guns were moved to the flanks to support the attack. Additional spare officers and gunnery crews were to join the infantry, ready to take over captured Turkish guns. To avoid the lines getting mixed up, officers were ordered to remain calm and not rush their troops. The cavalry should resort to their guns only when necessary, leaving the infantry units mixed among them to maintain a steady fire on the Turks. Eugene feared that even if Khalil was driven from the field premature looting could break up the imperial army and leave it at the mercy of a timely sally from Belgrade’s defenders. Any looting would be punishable by death.

During the night, Eugene visited his officers and soldiers. He issued orders and offered words of hope, personally handing out wine, brandy, and beer to boost the men’s courage. The Turks, he assured them, could be beaten if order was maintained and the imperial lines remained unbroken. His men’s confidence in their leader, who had fought the Turks for 30 years, remained high. Eugene knew in turn that he could count on his officers and soldiers, many of whom were battle-hardened veterans of the War of the Spanish Succession. Lieutenant Field Marshals Count Browne de Camus and Peter Josef de Viard remained behind to hold the trenches with 10,000 men, including cavalrymen whose horses had perished. They would continue the siege, guard the thousands of sick and wounded, and be ready to repulse any sortie out of Belgrade.

Before midnight three bombs exploded, signaling the advance. Eugene was back in the saddle. The trenches came to life and 50,000 imperial troopers filed out into the darkness beneath a clear, star-spangled night sky. The cavalry regiments, the elite of the imperial army, commanded by Hungarian Field Marshal Count Johann von Pálffy, were first to walk out of the openings on the left and right wings of the imperial entrenchment. While Palffy’s cavalry assembled in its squadrons, the infantry under Field Marshal Prince Alexander von Württemberg followed to form the imperial center. Fifteen battalions under Lieutenant Field Marshal Friedrich von Seckendorf stood in the reserve. In all, 52 infantry battalions, 53 grenadier companies, and 180 cavalry squadrons were coming for the Turks.

Fighting in the Fog

The imperial troopers did their best to dampen the sound of their battle gear and calm their horses. In places the Turkish lines were only a few hundred steps away. Vigilant Turkish guards heard the faintly audible clatter of steel blades, the tramp of boots and hoofs, the neighing of horses, and the foreign tongues of infidel officers giving orders to their men. A covering fog rose around 3 am on August 16. Into it marched the imperial pearl-gray lines, seemingly swallowed by the mist.

The Turks stared in disbelief as imperial cavalry suddenly rode out of the fog. Led by von Pálffy, the horsemen appeared practically on top of the Turks digging new trenches. No one could see more than 10 paces ahead. For a split second the Turks remained frozen, then alarms shattered the predawn air. The deafening clamor of massive kettle drums, clarinets, trumpets, and cymbals burst forth as the Ottoman military band urged on its troops.

Sitting on his horse, Eugene heard the first shots echo somewhere on his extreme right wing. The battle had begun—much too soon for Eugene’s liking. Inside the fog it was pure chaos. Everywhere the enemy was so close that artillery and musket fire were of little use. Imperial bayonets stabbed at red-clad Janissaries. Turks wielding two-handed axes ducked beneath flailing hoofs to hack at rearing imperial horses and riders. Pistol bullets ripped through Turkish shirts embroidered with verses from the Koran. Curved Yatagan swords parried the straight-bladed, heavy imperial cuirassier sabers.

On the Turkish left wing, Spahis galloped to the aid of the hard-pressed Turkish infantry. Pálffy’s horsemen seemed unable to batter their way through the Turkish defenses. Count Mercy boldly dashed forward with the second cavalry line. The Turks broke, but not for long, rallying and then viciously striking back. The first imperial infantry line, bristling with bayonets, appeared, led by Quartermaster-General Max von Starhemberg. The imperial cavalry rallied and struck the Turks in the flanks. This time the Turks fled for good, abandoning the higher ground and some batteries to the enemy. In the center of the line, other Turkish troops charged forward uncontested.

The Turkish Rout

Around 8 am, a strong morning breeze blew away the mist and revealed the terrible scene below. The battle raged on. The trenches were filled with Turkish and imperial dead. Eugene’s army was in dire peril. Instructed to stay close to the cavalry, the first line of imperial infantry had been led too far to the right by Pálffy’s disoriented horsemen. As a result, a gap had appeared in the imperial center, and into this gap poured untold masses of Turks.

There was no time to waste. If the Turks pushed any further, the imperial right wing would be severed and the battle surely lost. Eugene reacted with characteristic coolness and decisiveness. He galloped over to Prince von Braunschweig-Bevern’s second infantry line, which was not yet engaged. Sword in hand, Eugene personally rallied his men. With drum rolls and trumpet calls, Bevern’s men plowed into the Turks and pushed them back. The rapid fire of the imperial muskets mowed down the Turks, who shot back with slower matchlocks or charged with drawn swords. An endless human wave of Turkish soldiers, washing over the bodies of their fallen comrades, threatened to suffocate the imperials with their sheer numbers.

More help was needed, and Eugene was already on his way to get it. It was time for the cavalry reserves, whose horses nervously pawed the ground. Eugene’s sword glittered in the sun as the cuirassiers and hussars thundered into battle. Mounted on his white horse Eugene personally led the attack. It was Eugene’s last ride into battle. Like a battering ram, the imperial horsemen tore open the Turkish flanks. A musket ball hit Eugene’s arm, and his horse reared up in panic, threatening to throw its master, but Eugene reined him in and dashed farther into the fray.

A cry of despair rumbled over the Turkish hordes that were fleeing everywhere in heedless panic. On the Badjina Heights of the Turkish right wing, dense rows of crack Janissaries refused to give up the 18-gun grand battery. Their cannons blasted the imperial lines. To take the battery, Eugene gathered no less than 10 imperial grenadier battalions, three Bavarian infantry regiments, and two cavalry regiments. Unflinching in the face of cannon fire that ripped horrid gaps into their ranks, the imperial troops closed on the artillery barrels. With the call “Lower the bayonets!” the grenadiers and Bavarians overwhelmed the Janissaries, turning the captured guns on their former owners. The last centers of Turkish resistance collapsed. Bewildered at the rapid turn of events, Khalil ordered a retreat to save what he could of his army.

Around 9 am, Eugene and his troopers topped the crest of the hill and beheld the vast, multicolored Turkish tent city. Farther to the south, the Turks were still trying to escape. Cannons fired into the fleeing masses, which were mercilessly hunted down by Hungarian hussars and Serbian infantry. Eager to clear the path before them, some Turks even hacked down their own men.

Eugene’s Spoils of War

The Battle of Belgrade cost the Turks 20,000 dead, wounded, or captured. The imperials suffered 3,500 wounded, including Pálffy, von Württemberg, and the young Comte de Saxe. For Eugene, it was the 13th time he had been wounded in combat. Imperial dead amounted to 1,500, among them 17 generals and two lieutenant field marshals.

Upon the news of Eugene’s victory, all of Vienna broke out in jubilation. Eugene’s messenger had to dismount his horse to pass through the ecstatic masses. In front of the emperor and empress, the Jesuit preacher of the Cathedral of St. Stephan praised the divine intervention of “God’s victory in the fog.” Conquered flags and banners fluttered above the streets.

Back at Belgrade, Eugene’s unexpected victory so overwhelmed Mustafa Pasha that he was unable to react fast enough to come to the army’s aid. With Khalil Pasha’s army routed, Mustafa was on his own. Still, Mustafa was reluctant to surrender. The city retained supplies to last another six months and, while most of the town was leveled, the defenses were not yet breached. However, Mustafa’s soldiers thought otherwise. Many had wives and children in the city who continued to suffer from the imperial bombardment. When his soldiers began to grumble of revolt, Mustafa decided to answer Eugene’s offer of safe passage in exchange for the surrender of Belgrade.

Eugene’s white horse trod over the ruins of Belgrade’s crumbled walls. From his saddle he surveyed the fallen city, the field of battle, and the columns of soldiers behind him. Eugene lifted his hat as a joyous roar of approval split the air, causing his horse to rear up on its hind legs.

Mustafa’s trust in Eugene, who had treated Mustafa and his soldiers honorably after the earlier conquest of Temesvár, was not misplaced. Despite the grueling siege and battle, Eugene managed to curtail his troops and spare the city any major carnage. On August 22, 60,000 Muslims, among them 20,000 Janissaries, filed out of Belgrade’s gates with their personal belongings and 300 carriages and 1,000 camels. Curious imperial soldiers gazed at the Muslim women, whose dark eyes were all that could be seen of their shrouded faces.

Along with Belgrade, Eugene netted 15 Turkish galleys and hundreds of additional cannons. The prince had no wish to push the war further into Turkish-occupied territory. Not only would the distances involved create supply problems, but the deteriorating political situation in the west made it prudent to reach a quick conclusion to the war. King Philip V of Spain had already sent his fleet to seize Sardinia from the Austrians. With the Austrian possessions in Italy under increasing Spanish threat, Emperor Charles VI pressured Eugene to free up his troops from the Balkans.

A 25-Year Truce

Negotiations dragged on until July 21, 1718, with Eugene keeping mostly aloof, although at times he mobilized his troops in such a way as to frighten the Turks into quicker acceptance of imperial terms. He met the Grand Vizier at Serbian village of Passarowitz to open the peace conference. The Treaty of Passarowitz between Emperor Charles VI and Sultan Ahmed III, mediated by England and Holland, secured a 25-year truce and relinquished the Banat of Temesvár, Belgrade, western Wallachia, and part of Serbia and Bosnia to Austria. The Ottomans managed to retain their Morean conquests—the reason the Empire had allegedly gone to war with the Turks in the first place.

Belgrade proved to be Eugene’s last great battle. He retired from active military service, although he remained the emperor’s primary adviser. For his services at Belgrade, Charles rewarded Eugene with a diamond-studded sword. He mildly chastised Eugene for personally taking part in the battle, observing, “If you had not survived, the greatest victory of all time would have been a tragedy and meant an irreplaceable loss.”

At elite European social gatherings, lords and ladies marveled at Eugene’s war trophies. Poets, painters, and historians immortalized Eugene’s deeds. But perhaps the most appropriate tribute to Eugene was the famous folk song and later imperial cavalry march, “Prinz Eugen Lied.” Composed by a Bavarian veteran of Belgrade, it was sung by imperial soldiers marching into battle for ages to come.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments