By Daniel Murphy

In late March 1781, American Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene sought to make the best of a bad situation. He had just lost a pitched battle against the British at Guilford Courthouse, in the North Carolina piedmont. Yet the victory was hollow at best; the British commander, Lord Charles Cornwallis, had taken the ground but Greene had inflicted so many casualties upon the hard-charging British that His Lordship was forced to leave his wounded behind and limp away in search of supplies. Most commanders would have pursued the battered British army and attempted to run it into the ground, but Greene took a different approach. It would change the entire course of the war.

By 1781, Greene was no stranger to war. A former forge master and member of the Rhode Island General Assembly, he had enlisted as a private in the militia but was quickly recognized as an emerging talent. The Continental Congress had promoted him to general officer in June 1775. Quickly, Greene became a trusted lieutenant, friend, and adviser to commanding General George Washington. Greene’s record was unimpressive at first, and he erred heavily in his judgment to defend Fort Washington in 1776. That led to a costly defeat, but Greene later proved his capacity at Trenton, Germantown, and Monmouth. However, it was not until Greene grudgingly accepted the post of quartermaster general that his remarkable talent for military administration was revealed.

Greene Takes Command of the Southern Theater

The lessons Greene had learned running the family forge in Rhode Island proved perfectly suited to a quartermaster’s tasks of securing supplies and purchasing materials, and his prior political experience aided him greatly in petitioning funds from Congress. At the same time, Greene was also learning how to move an army, select campsites, choose river crossings, secure routes of march, and collect supplies in the field—all vital skills for a general officer on campaign. When a new commander was needed to replace General Horatio Gates in the wild and sparsely populated southern theater, Washington did not have to look far for a substitute—Nathanael Greene.

Greene took command of the southern theater in the fall of 1780, inheriting a fractured force of trained Continental regulars and scattered state militias that to date had been outfought and outgeneraled by the British. The Americans had lost the greater part of South Carolina and with it Charleston, the richest port in North America. With his keen quartermaster’s eye, Greene set about culling the best troops of his new command and forming a flying corps of militia, light infantry, and cavalry to operate on the British flank.

Under Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan, the Americans scored a dazzling success at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781. The game-changing victory drew the immediate wrath of Greene’s British counterpart, Lord Cornwallis, who decided to come after Greene and crush the new threat at all costs. Greene felt his army was too weak to offer pitched battle to Cornwallis. Instead, he retreated across North Carolina with Cornwallis nipping at his heels the entire way. At times Cornwallis was mere hours away, but Greene’s experience as a quartermaster shone brilliantly; the Americans were always a half step ahead, fighting a series of delaying actions that steadily drew the British farther and farther from their main base of supply in Charleston.

Aftermath of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse

On February 13, Greene crossed the bridgeless Dan River and had every available boat moved over to the northern bank before Cornwallis’s troops reached the southern side. The half-starved British could only stare with exhausted hatred across the flooded expanse of deep water. Cornwallis was forced to give up the chase and turn south to try to feed his men, while Greene welcomed new supplies and fresh troops sent down from Virginia by Governor Thomas Jefferson.

His ranks now swelling with fresh militia, Greene crossed back into North Carolina and met Cornwallis at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1781. Greene lost the fight and surrendered the field, but suffered low casualties, while Cornwallis lost nearly a third of his force, including five field officers. Combined with months of hard winter marching, the losses at Guilford effectively crippled Cornwallis’s offensive capabilities. He was now so short on food and supplies that he was forced to give up his pursuit of Greene and leave his wounded behind at Guilford while he began a 200-mile march toward Wilmington, North Carolina, and a desperately needed cache of supplies waiting there.

As Cornwallis and his men marched toward Wilmington, Greene followed as far as the Deep River, watching his adversary and reviewing his options. Despite losing four pieces of artillery, Greene’s force had come through the fight at Guilford Courthouse largely intact and in good spirits. Unfortunately, the short-term militias that had allowed Greene to give battle had concluded their terms of service and left for home, leaving him with roughly the same size force of combat-ready troops as Cornwallis. The loss of artillery now loomed large. Without reinforcements, and with Cornwallis’s definitive edge in field guns, Greene was wary of risking a direct attack on the British force. All he could do was to continue following Cornwallis, harassing his march and dogging his flanks. Greene began to look south for a new plan of attack.

“Carry the War Immediately Into South Carolina”

When Cornwallis had taken after Greene two months earlier, he had left behind a strong line of frontier forts and outposts that fanned out from Charleston across the interior of South Carolina, along with a force of 8,000 men to guard it. On paper those were imposing numbers, but they failed to tell the whole story. Despite being occupied by foreign troops, the people of South Carolina’s interior, or “backcountry,” had refused to surrender. The sparsely settled frontier section of the state had seen a never-ending series of sharp fights and skirmishes that had only increased in the wake of the American victory at Cowpens the previous January. Far from being secure, the string of interior British garrisons was constantly under fire from partisan rangers under Generals Francis Marion, Andrew Pickens and Thomas Sumter. If the partisans could continue to press the British and pin them to their respective posts, there was an excellent opportunity for Greene and his soldiers to steal a march into South Carolina and topple the backcountry British forts one at a time.

On March 23, Greene informed the Continental Congress that “nothing will be left unattempted” in the southern department. If Cornwallis turned from Wilmington and pursued him into South Carolina, Greene would have succeeded in relieving North Carolina of the enemy presence without firing a shot—Cornwallis would essentially be back where he had started two months earlier. If Cornwallis stayed put, Greene felt the odds were ripe for taking the entire string of South Carolina forts, liberating the vast majority of South Carolina, and further isolating Cornwallis in North Carolina.

As Greene looked south he set his sights on the key British garrison at Camden. He wrote to George Washington on March 29 that he was “determined to carry the war immediately into South Carolina.”

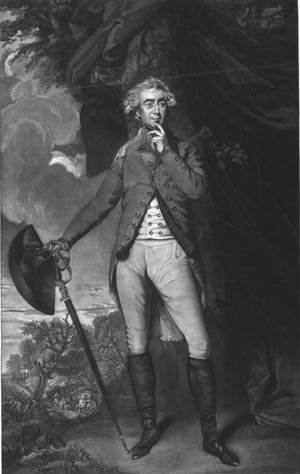

The Camden Garrison

The British commander at Camden was Colonel George Augustus Francis Rawdon. Just 26, Lord Rawdon had been born into an Irish peerage and grown up in the lap of luxury. Tall, dark, brave and energetic, he was nonetheless reputed to be the ugliest officer in the British Army. He first saw combat as a lieutenant at Bunker Hill in 1775, where he took command of his company after his own captain was shot. For the courage he displayed during his baptism of fire, Rawdon was promoted to captain and given a company in the 63rd Foot. Less than a year later, he joined General Sir Henry Clinton’s staff and saw further action at the Battles of Brooklyn, White Plains, and Monmouth. In 1780, Rawdon was given his own loyalist regiment, the Volunteers of Ireland, and promoted to colonel. He then accompanied his new regiment south and arrived during the siege of Charleston. Cornwallis had such faith in the young lord’s abilities that he not only gave him command of the post at Camden but also left Rawdon in overall command of the South Carolina garrisons when he began his pursuit of Greene.

The post at Camden was one of the most important in the line of British garrisons. It commanded a crucial intersection of backcountry roads and consisted of four redoubts, one at each corner of the town, with a large stockade of high walls in the center. Half a mile north of the town proper, on the Great Waxhaws Road, was a second fortified position known as Log Town. Aside from housing a garrison force of nearly 2,000 troops, Camden served as a stern reminder of the king’s presence to all civilians in the area, and rebel partisans steered clear of the post. Executions for treason against the Crown were held so often in Camden that the local populace began to view the hangings as routine. Perhaps due in part to this regular brand of the Crown’s justice, most of Camden’s residents were loyal subjects to King George III and provided Rawdon with a steady stream of information. This private intelligence, along with regular reports from Cornwallis and the neighboring string of outposts, kept Rawdon reasonably well informed of the constantly shifting tides of war.

Watching and Waiting

Aside from Cornwallis’s victory at Guilford Courthouse, the news had taken a decidedly bad turn for the British. To the west, Major James Dunlap’s entire force had been wiped out at Beatties Mill by American dragoons under the command of Elijah Clarke and James McCall. Things were no better to the east of Camden, where Francis Marion’s partisans were operating with such impunity that Rawdon dispatched 500 men from his own garrison under Lt. Col. John Watson to run down Marion once and for all. Instead, Watson’s force was ambushed at Sampit Bridge and driven back into Georgetown. By early April, loyalist farmers began reporting a large force of Continental troops moving into South Carolina under Greene. With pressure mounting from all sides, there was little Rawdon could do but wait and hope for Watson’s return as sightings of Continental forces increased by the day.

Emboldened American partisans now stole into Camden itself and raided the town mill. The partisans were chased off by Rawdon’s cavalry, but the attack was a foreboding sign of the future. Local farmers began seeing Continental forces less than a day’s march from Camden.

On the evening of April 19, musketry suddenly erupted a half mile north of Camden at Log Town. This was clearly no partisan raid; the firing continued throughout the night. At dawn, a sharp skirmish ended the affair, with the British pickets retreating into Camden under fire from Continental light infantry. The guessing game was over—Greene had arrived and was clearly spoiling for a fight.

Greene peered out from the walls of Log Town and studied the distant works at Camden. If he had been a swearing man, he might well have uttered a string of oaths as he took in the formidable British position for the first time and realized that he simply did not have the manpower to assault or invest the post. Greene had been promised a significant force of additional state troops from militia General Sumter, but that aid had as yet failed to arrive. Still, all was not lost. Greene had already issued orders for Lt. Col. Henry Lee to link up with Marion and harass enemy posts east of Camden, thereby denying Rawdon communication or reinforcements from that sector. To date, Greene had heard no word from Lee. He decided to fall back and wait for reinforcements.

As Rawdon watched Greene withdraw from Log Town, he was also looking to the east for the return of his still-missing force of 500 men under Watson. Rawdon still had nearly 1,000 men under arms within Camden, more than enough to keep Greene at bay but hardly enough to sally forth and attack with any certainty of success. Like Greene, all Rawdon could do for now was watch and wait.

Greene’s Position on Hobkirk’s Hill

The stalemate came to an end when a dispatch arrived for Greene from Lee. To Greene’s relief, Lee had been successful in linking with Marion and the pair had laid siege to Fort Watson, a smaller British outpost east of Camden. The dispatch also warned Greene of the fort’s namesake, Watson, and his expected advance on Camden from Georgetown to relieve Rawdon. Watson’s sizable force would certainly tip the scales for Rawdon, and Greene was compelled to shift his force to the east, fording a pair of creeks and a swamp to effectively screen Watson’s pending advance. Once in position, Greene received a pair of sorely needed cannon from North Carolina and instantly sent one off in support of Lee and Marion. Soon after dispatching the piece, he received a second encouraging message from Lee: Fort Watson would fall at any moment, freeing Lee and Marion to block Watson’s advance.

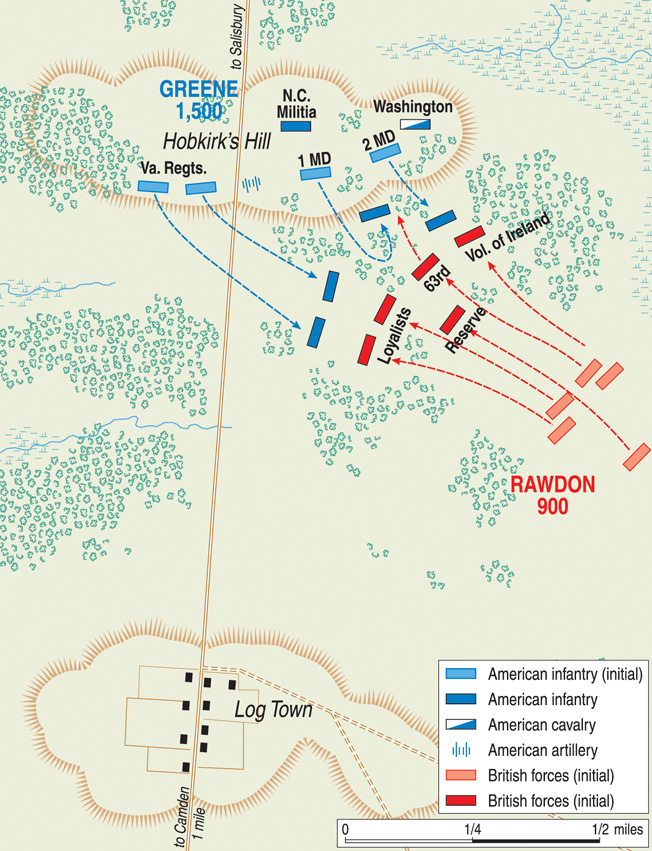

Greene now looked back to Camden and set his men to felling trees and building a rough causeway across the swamp to pass his remaining gun to the north side of Camden. This passage would allow Greene to rapidly move to either side of the town, but the Herculean task took several days to complete. It was not until the evening of April 24 that Greene had most of his 1,200 men back across the swamp and camped on a narrow, wooded ridge just north of Camden known locally as Hobkirk’s Hill.

That same night, an American drummer deserted and stole his way into the British lines at Camden. Brought before Rawdon, the deserter talked freely, and the news was not good. Fort Watson had fallen to Lee and Marion on the 23rd. Watson was days if not weeks away, and Greene was expecting reinforcements at any moment. Worse still, Greene had received a pair of guns that he would soon have in place. The only good news from Rawdon’s perspective was that Greene had not yet had time to dig entrenchments or place his guns in his new position on Hobkirk’s Hill. Rawdon knew that time was running out. His best hope was to launch a surprise attack as soon as possible. With any luck, he could cripple Greene’s force before the American commander improved his position or received reinforcements.

Rawdon went about arming every available man for the assault: musicians, wagon masters, and surgeon’s assistants—anyone who could load and carry a musket. The entire British force numbered only 950 men, and Rawdon issued strict orders for the men to march in silence. At 10 am on April 25, the British columns left Camden and crept through the concealing woods along Pine Tree Creek. They did not have far to go. Hobkirk’s Hill lay just a mile to the north.

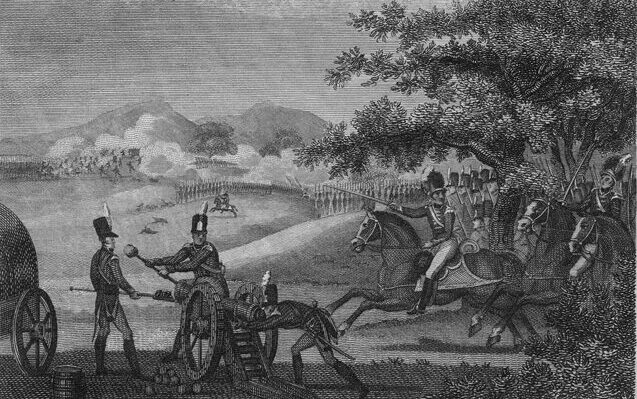

The Battle of Hobkirk Hill

More ridge than hill, the steep, sandy eminence was covered with trees and bisected by the Great Waxhaws Road, which ran straight up the southern slope facing the town. The slope was flanked to the east by a large spring that flowed down to form a swampy stretch of wooded ground that Rawdon’s men used for their approach. A second road ran southeast from the eastern side of the hill to Kershaw’s Mill, and a third, more obscure road ran directly into town from the east, paralleling the Waxhaws Road.

Atop the hill, Greene’s men had completed their morning drill and had just been issued their first full ration of food since leaving North Carolina. The rations were cause for celebration; arms were stacked and horses were tethered. A gill of rum was issued to each man, and the oily blue smoke of cooking fires wafted fragrantly through camp. After weeks of marching and endless labor, many of the men were taking the rare opportunity to soak their tired feet or wash their clothes in the nearby spring.

The Patriots’ respite was cut short when the sharp crash of musketry split the morning air. Captain Robert Kirkwood of the Delaware line was one of the first to respond, quickly forming his light infantry and rushing down the hill to assist the startled pickets. The firing increased as he went, and Kirkwood found no simple skirmish between sentries but a stiff fight forming in the dense pines at the base of the hill. “The woods,” he said, “were so thick that a man could not be seen at 100 yards distance.”

As Kirkwood’s men began returning fire, Greene formed the rest of his troops for battle on the crest of the hill. The night before he had posted the 1st and 2nd Virginia Regiments to the west of the Waxhaws Road. Extending to the east was the 1st Maryland, and to their left the 2nd Maryland, whose ranks ran down to the spring. The 3rd Light Dragoons were quickly mounted and placed in reserve with the North Carolina militia. In a stroke of good fortune for the Americans, Colonel Charles Harrison had arrived earlier that morning with three pieces of artillery. He now positioned two of the 6-pounders along the Waxhaws Road and the third between the two Maryland regiments. There was no time for adjustments, and Greene waved his men into line where they had camped, many of them still half-dressed and barefoot as they grabbed their muskets and rushed into action.

“Universal Blaze of Musketry”

Down at the base of the hill, Kirkwood’s Delaware troops and the previously posted pickets were caught in the midst of a “universal blaze of musketry.” Concentrated British firepower eventually drove them out of the pines and into the more open area at the eastern slope of the hill. Much like Greene, Rawdon was urging his men forward in the order that they had marched. Bursting from the tree line in a narrow front, the 63rd Foot was on the right and the King’s American Regiment was on the left.

From the top of the hill, Harrison’s gunners looked down at the concentrated mass of enemy troops and opened fire, shredding the tightly packed ranks with grapeshot and literally bowling over the British like ninepins. As the smoke cleared, Greene saw the destruction wrought by his guns and felt the battle was practically won. Without full knowledge of Rawdon’s forces, he seized the initiative and ordered his two center regiments, the 1st Maryland and 2nd Virginia, to advance with bayonets and charge the enemy from the front, while his flank regiments, the 2nd Maryland on the left and 1st Virginia on the right, moved down the hill to take Rawdon’s columns in either flank. To complete his perceived rout, Greene sent his mounted reserve under Lt. Col. William Washington forward with orders to turn the enemy’s right flank and charge them in the rear.

The 3rd Light Dragoons formed and advanced down the hill, skirting the enemy flank and running point blank into the British troopers of Major John Coffin’s Mounted Infantry. With swords aloft, Washington’s men made a spirited charge on the British horsemen and dispersed them, then plowed through the British right flank, falling upon their rear. Washington’s men took upwards of 200 prisoners. Unbeknownst to Washington, the infantry in the British rear was Rawdon’s ad hoc corps of armed musicians and teamsters, who quickly surrendered at the sight of the charging Patriots.

Wavering American Lines

Meanwhile, Rawdon was nearly beside himself with rage as the Continental artillery shredded his ranks. He had been told that Greene had no guns; now his men were paying the price for this misinformation before his very eyes. Rawdon saw the Continentals charging forward and quickly extended his front while ordering forward his reserves. The onrushing Continentals blocked the fire of their own artillery, and the British Provincials rallied as Rawdon’s Volunteers of Ireland came up and added their fire at the Maryland ranks. Aside from the 63rd Foot, all of Rawdon’s troops were American loyalists fighting their own countrymen in the Continental ranks. Volley after volley crashed through the open woods on the sloping hill as men fired, bit open fresh cartridges and hurriedly ran them down barrels quickly growing too hot to hold.

The veteran 1st Maryland was bravely advancing in the face of heavy fire when Captain William Beatty, commander of the two right flank companies, was shot and killed. The two flanking companies stalled as the rest of the regiment continued forward, bowing the regiment’s front and creating disorder. The 1st Maryland commander, Lt. Col. John Gunby, ordered the center companies to halt and back up to redress the ranks and realign the companies. The British charged at the same time, and the 1st Maryland broke for the rear in a panic. On their left, the commander of the 2nd Maryland, Lt. Col. Benjamin Ford, was hit with a musket ball that shattered his elbow. Seeing the 1st Maryland fleeing in disorder and its own commander wounded and out of action, the 2nd Maryland also took to its heels. The 1st Virginia then bolted in turn, streaming up the slope en masse despite the shouts and pleas of its officers to stand and fire. In a matter of seconds, the momentum shifted from Greene to Rawdon.

Smelling blood, the British charged up the slope on the heels of the Continentals. Greene could hardly believe his eyes. He ordered the horse teams forward to limber their guns and carry them to the rear. Gunby managed to rally the 1st Maryland and directed a few volleys, but it was too little too late. Only Lt. Col. Samuel Hawes’s 2nd Virginia made a stand, preventing the American withdrawal from becoming a complete rout. Soon Greene ordered their withdrawal as well.

Saving the Patriots’ Guns

Swept up in the tide of retreating troops, the Continental gunners atop the hill mishandled their teams and snagged their limbers in heavy brush. The horses panicked, and the teams had to be cut from the traces. Greene rushed forward on horseback to help save the guns and ordered Captain John Smith’s company of light infantry to cover the guns’ withdrawal. Smith’s men grabbed the trail ropes and took off at a trot down the Waxhaws Road. Rallying from their earlier rout by Washington’s light dragoons, Coffin’s mounted infantry charged over the hill and made for the guns. Smith’s men dropped the ropes, turned, and fired, pouring volley after volley into the British troops and temporarily checking Coffin’s advance.

As soon as Washington determined that Greene was withdrawing, he immediately mounted a handful of captured British officers and turned his dragoons in the direction of Hobkirk’s Hill, looping past the surging enemy infantry to regain the safety of the American lines. Washington delivered his prisoners into American hands and then led his men back onto the road where Coffin’s British horsemen were attempting to wrestle the guns from Smith’s infantry in a running fight along the roadbed. After a series of halting charges, Coffin’s men baited the light infantry’s fire and dashed among them with sabers flashing, killing several and capturing Smith.

The time bought by Smith’s men saved the guns. Washington’s dragoons charged into Coffin’s troopers and cleaved the British horsemen from their saddles until the remainder took to their heels. The guns remained in Continental hands. Greene’s men continued their withdrawal down the Waxhaws Road until they reached Sanders’ Creek, where they halted three miles from Hobkirk’s Hill. The militia and some stragglers took a different route and considerably more time before they rallied at the creek.

“His Majesty’s Troops Behaved Most Gallantly”

Within minutes, the battle was over. Rawdon set about burying the dead in two massive common graves on either side of the ridge and withdrew to Camden before nightfall. American casualties were 25 killed, 108 wounded, and 136 missing. British losses totaled 39 killed and 210 wounded, with up to 70 more captured. Like Cornwallis at Guilford Courthouse, Rawdon had suffered a higher rate of casualties than the Americans while failing to inflict a crippling blow on Greene’s force.

Nevertheless, Rawdon was justifiably proud of his men’s performance, writing to Cornwallis that “His Majesty’s troops behaved most gallantly.” Greene on the other hand, was livid with anger. Despite holding the high ground and a clear advantage in artillery, Greene’s lines had been broken quickly, and he had been driven from the field. He admitted privately to a friend that he was “almost frantic with vexation at the disappointment,” adding, “We should have had Lord Rawdon and his whole command prisoners in three minutes.” Colonel Williams, commander of Greene’s left wing, shared the feeling. “The cavalry, the light infantry and the guards [pickets] acquired all the honor,” wrote Washington, “and the infantry of the battalions all the disgrace which fell upon our brows and shoulders.” Greene echoed the praise of Washington’s cavalry in a letter to Congress, while observing that the infantry “had got into too much disorder to recover the fortune of the day, which once promised us a complete victory.”

A Strategically Inconsequential Battle

Despite heroic sacrifices made on both sides, the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill had little immediate effect on the overall situation. Greene remained in the general area and continued haunting Camden, while audacious partisans continued to harass the backcountry. The constant pressure on Rawdon’s lines of supply and communication soon made the British position at Camden untenable. Rawdon retreated from the key post just two weeks after winning the fight at Hobkirk’s Hill.

Ultimately, Greene’s invasion of South Carolina led to the successful conclusion of the war. After refitting in Wilmington, Cornwallis looked north to Virginia, where fellow general William Phillips was enjoying marked success in raiding the provision-rich and lightly defended Chesapeake Bay. Having already tested Greene in the Carolinas, Cornwallis abruptly turned his back on Rawdon and the line of backcountry garrisons and headed north for Virginia, where he ultimately met a disastrous fate at Yorktown.

By summer’s end, the British line of interior garrisons had all fallen, and the vast majority of both North and South Carolina were liberated from British troops. From his camp on the high hills of the Santee River, Greene joked to his friend General Henry Knox: “There are few Generals that has run oftener, or more lustily than I have done. But I have taken care not to run too far, and commonly have run as fast forward as backward.”

In the end, it turned out to be the perfect strategy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments