By John Protasio

When World War I broke out in August 1914, the captains of the various German warships called their men together to give three cheers for the Kaiser. The 53-year-old commander of the East Asiatic Squadron, Maximilian Graf von Spee, personally climbed atop the turret of an 8.2-inch gun aboard the cruiser Gneisenau and addressed his crew. They must be faithful to their oath to the Kaiser, he reminded them. “At the moment,” the Admiral added, “only Russia and France are our enemies. England’s attitude is still uncertain, although hostile. We must therefore regard all English ships as enemy ships.”

When Britain entered the war against Germany, Spee ordered all his ships to meet him in the Mariana Islands. There, the admiral called a conference of his captains. He expressed the belief that it would be best for the squadron to continue sailing to the west coast of South America and raid British merchant ships. Each captain was asked for his views. Karl von Muller, Emden’s skipper, believed that such raids would not be worthwhile. He suggested instead that they remain in Asiatic waters. Why not allow Emden to act independently as a raider in the Indian Ocean? Spee granted Muller’s request.

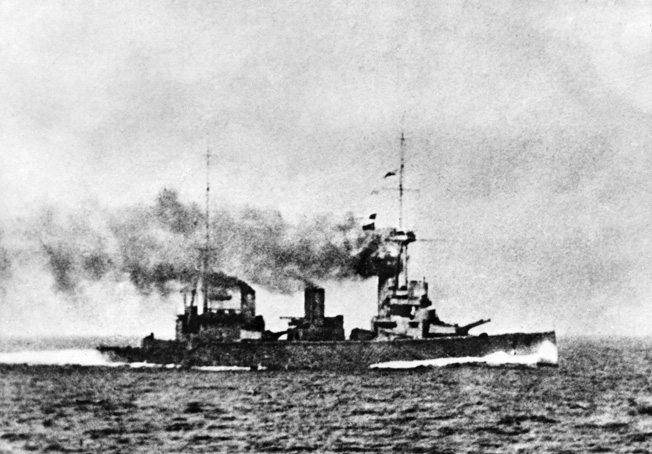

With Emden gone, Spee was left with only Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and the light cruisers Leipzig and Nürnberg. A short time later, the East Asiatic Squadron was reinforced by the arrival of the light cruiser Dresden. As commander in chief of the East Asiastic Squadron, Spee faced many problems. He knew that his base in Asiatic waters, Tsingtao, China, would fall if Japan entered the war. His ships would have no facilities to make repairs, and he would be unable to replace ammunition when he ran out. Then there was coal. His ship could travel at top speed for four and a half days, or 2,200 miles. At economic speed it could go 5,000 miles. Either way, coal would be difficult to obtain.

Count Spee’s Rise as a Naval Officer

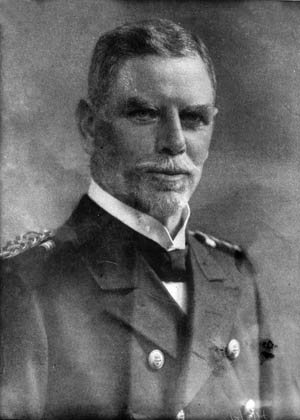

Confronted by such difficulties, Spee feared that the days of the East Asiatic Squadron were numbered. Before then, however, he was determined to do as much damage to the Allies as he could. He was the right man for the job. Although Spee was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, he was one in a long line of German counts. He received a strict Catholic education during his youth. At the age of 16 he joined the German Imperial Navy as a cadet.

Spee took an active part in Germany’s seizure of colonies. In April 1884, he was promoted to full lieutenant. When German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck chose Dr. Gustav Nachtigal to colonize Africa, Spee accompanied him there. By 1897, he was flag lieutenant of the 7,300-ton cruiser Deutschland that carried Prince Heinrich of Prussia to the Far East. A fellow officer described Spee at the time as “a favorite in the wardroom. He made everyone his friend by his invariable kindness. I believe I can say without exaggeration that none of us ever found even the slightest fault with Count Spee.”

With the new century, Spee continued to climb the ladder of success. In November 1912, he was appointed to command the East Asiatic Squadron with the rank of rear admiral. The new commander in chief was a tall, well-built man with a Van Dyke beard, bushy eyebrows, and a straight back—one of his colleagues said he looked as though he had swallowed a broom handle. A devout Catholic, Spee had a passion for natural history and auction bridge. He had a wide variety of flowers decorating his cabin.

As commander of the squadron, Spee was a strict taskmaster. He held frequent gunnery and torpedo practice. Coaling at sea was rehearsed until it could be performed like a fine art. The policy paid off when Spee’s squadron twice won the Kaiser’s Cup for marksmanship. A British naval correspondent observed: “The German squadron was like no other in the Kaiser’s Navy. It was commanded by professional officers and manned by long service ratings.”

To Stop Admiral Spee

In the early hours of September 7, 1914, Nürnberg raided Fanning Island, where there was a British wireless and cable station. After Nürnberg rejoined the squadron, Spee learned from newspapers that the Allied warships New Zealand and Tromp had captured Samoa and that the British battleship Australia was anchored there. He decided to raid Samoa and catch the enemy by surprise. He detached Scharnhorst and Geneisenau from the squadron and headed for Samoa. On September 13, the German heavy cruisers arrived, but to Spee’s disappointment Australia and other Allied warships were not there. The only vessels in harbor were an American schooner and a small sailing ship.

Undeterred, a few days later Spee raided Tahiti. The guns at the French fort opened fire and straddled Scharnhorst. The French hastily burned their coal supply to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. The Germans fired on the shore batteries and destroyed them and sank the 600-ton gunboat Zelee.

The British Admiralty was determined to stop Spee at any cost. On September 14, a telegram was sent to Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock reading: “The Germans are resuming trade on West Coast of South America, and Scharnhorst and Gneisenau may very probably arrive on that coast or in Magellan Straits. Concentrate a squadron strong enough to meet Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, making Falkland Islands your coaling base, and leaving sufficient force to deal with Dresden and Karlsruhe.

“Defence is joining you from Mediterranean, and Canopus is now en route to Abrolhos. You should keep at least one County class and Canopus with your flagship until Defence joins. When you have superior force you should at once search Magellan Straits with squadron, keeping readiness to return and cover River Plate, or, according to information, search as far as Valparaiso northwards, destroy the German cruisers, and break up the German trade.”

On October 5, the Admiralty sent Cradock a follow-up telegram: “It appears from information received that Gneisenau and Scharnhorst are working across to South America. Dresden may be scouting for them. You must be prepared to meet them in company. Canopus should accompany Glasgow, Monmouth and Otranto and should search and protect trade in combination.”

Cradock replied: “Without alarming, respectfully suggest that, in event of the enemy’s heavy cruisers and others concentrating West Coast of South America, it is necessary to have a British force on each coast strong enough to bring them to action. For, otherwise, should the concentrated British force sent from South-East Coast be evaded in the Pacific, which is not impossible, and thereby get behind the enemy, the latter could destroy Falkland, English Bank, and Abrolhos coaling bases in turn with little to stop them and with British ships unable to follow up owing to want of coal enemy might possibly reach West Indies.”

The Admiralty concurred in Cradock’s decision to concentrate Canopus, Good Hope, Glasgow, Monmouth, and Otranto for combined operations. Cradock knew that with Canopus, a pre-dreadnought battleship, his unit speed could not exceed 12 knots. This was a severe handicap since Spee’s ships were capable of reaching 20 knots. Cradock complained to the Admiralty: “I consider that owing to slow speed of Canopus it is impossible to find and destroy enemy’s squadron. Have therefore ordered Defence to join me after calling for orders at Montevideo. Shall employ Canopus on necessary work of convoying colliers.”

“I Shall Not See You Again”

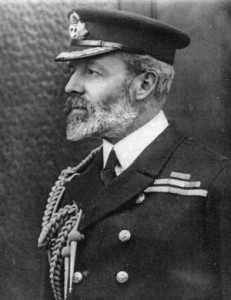

The man receiving and sending these telegrams had a wealth of seagoing experience. Kit Cradock had joined the Royal Navy at the age of 13. He subsequently participated in the Boer War and the Boxer Rebellion. In 1900, he led a combined British, German, Japanese and Italian naval force against the Boxer-held Taku Forts on the Peiho River. Fighting was intense, but he managed to capture the forts.

Like Spee, Cradock was a man of refined tastes and interests. He enjoyed hunting and also found the time to write three books, the last of which, Whispers from the Fleet, served as a guide book for young naval officers. By late October 1914, Cradock was out at sea again. He had under his command the flagship Good Hope, along with another heavy cruiser, Monmouth, the light cruiser Glasgow, and the armed merchant cruiser Otranto. Cradock knew that Spee had a superior force, but he was determined to fight.

Cradock’s force could have been stronger if he had Canopus, mounting 12-inch guns. But Canopus was suffering from a leaking piston-rod and could make only 12 knots. The admiral knew that he could not catch Spee with the lagging vessel in hand, so he left her behind.

Cradock was well aware that he might be defeated. While he was at the Falklands, he told the governor there, Sir William Allardyce: “I shall not see you again. I will send my medals and decorations ashore to you for safe-keeping. If the Germans do come here and occupy these islands, will you bury them? Then when the war is over I would be grateful if you would send them home to my people.”

On October 31, Cradock sent Glasgow into Coronel Bay, Chile, to collect telegrams. Her captain, John Luce, was worried that he might not be able to rejoin Cradock in time if the enemy was sighted. His wireless had already picked up signals from Leipzig. Perhaps the rest of the German East Asiatic Squadron was nearby. Glasgow rejoined Cradock. The seas were too rough for boats, so the light cruiser towed a cask containing the telegrams across to Good Hope. Cradock ordered his ships to form a line. Good Hope was to the west with Glasgow to the east. It was the admiral’s hope to catch Leipzig alone. The force under his command was sufficient to handle a lone ship.

Spee Keeps His Distance

Spee was preparing for battle as well. He had heard that Glasgow was nearby. The German admiral assumed, like Cradock, that he would be facing only one small cruiser. Each man was wrong.

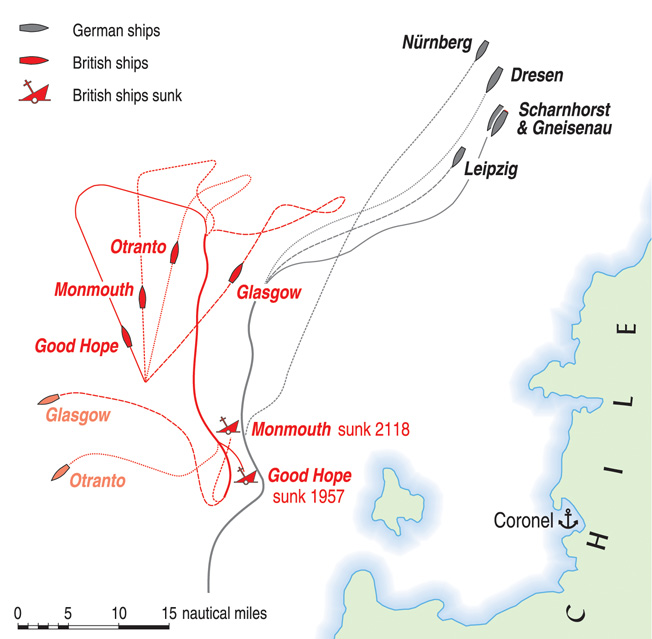

At 4:25 pm on November 1, Glasgow saw smoke. Luce notified Cradock of the development and then moved to the starboard to investigate. A few minutes later, lookouts saw Scharnhorst and Gneisenau with Leipzig astern. Glasgow turned back and tried to inform the flagship of Spee’s presence, but the German vessels’ wireless jammed the British cruiser’s radio. By 4:45, Cradock realized that Spee’s ships were in the vicinity.

Cradock was at a serious disadvantage. His flagship was capable of 23 knots and armed with two 9.2-inch guns and 16 6-inch guns. Monmouth had a speed of 22.4 knots and was armed with 14 6-inch guns, Glasgow had a speed of 25.3 knots with two 6-inch guns and 10 4-inch guns, and Ontranto had a speed of only 15 knots and was equipped with four 4.7-inch guns.

Spee’s force was clearly superior. The flagship Scharnhorst was capable of 23.2 knots and armed with eight 8.2-inch guns, six 5.9-inch guns and 18 22-pounders. Gneisenau had a speed of 23.5 knots and was similarly armed. Leipzig was capable of 22.4 knots, Dresden 24 knots, and Nürnberg 23.5 knots. The three light cruisers were armed with 10 4.1-inch guns. In all, the Germans presented a broadside of 3,812 pounds to the British 2,815 pounds. Another advantage Spee had was that most of his men were experienced seamen, while 90 percent of Good Hope’s crew were reservists.

Cradock was faced with the toughest decision in his career: should he attack or retire? He dearly wished to have Canopus with her 12-inch guns, but she was over 200 miles away. His orders were to protect British shipping, and to do so meant that he had to attack. Cradock made his decision. At 6:18 he signaled Canopus, “I am going to attack the enemy now!” He gave his position as “Lat. 370 30’ S. Long. 740 0’ W.” This was actually some 50 miles south of where he was. Cradock signaled his ships to follow in the admiral’s wake.

The captain of Otranto signaled Cradock asking whether he should stay out of range. The reply was, “There is danger; proceed at your utmost speed…” The message was not completed. Meanwhile, Cradock moved to the southeast. It was apparently his intention to position himself so that the wind would blow his smoke clear of his gun crew and at the same time Scharnhorst’s smoke would blow across the German sights.

Spee kept his distance from the enemy. Cradock had a chance if he could cross the German “T” to bring his broadside to bear while the enemy could only fire his foreguns. But the slow-moving Otranto prevented this from happening. Cradock had one last hope. If he could position himself between the enemy ships and the sun this would help tremendously. The sun would be in the eyes of the German gun crews. But the wily Spee kept his distance and waited for the sun to set.

Shots in the Dark

Cradock turned back to a southerly course. He began to reform his battle line. The British admiral observed Leipzig coming up and Dresden steaming up from the horizon. He knew Nürnberg was not far away. The sea was rough. The British guns were awash and spray drenched the telescopes and gun sights. The Germans by contrast had their guns high above the waterline and were dry.

Spee ordered all his boilers to be lighted and quickly increased his speed from 14 knots to 20. “The wind was south,” he later explained, “force 6, with a correspondingly high sea, so that I had to be careful not to be maneuvered into a lee position. Moreover, the course chosen helped to cut off the enemy from the neutral coast.”

Soon, the sun set. Now the advantage of light was with the Germans. Spee’s ships were in darkness while the British were illuminated in the afterglow. He moved his ships into position. At 7:04 pm, the Germans opened up with their 8.2-inch guns at a range of 12,000 yards. The shells came within 500 yards of Good Hope. Glasgow responded by firing her 6-inch guns. The Battle of Coronel had begun.

The sea was not favorable. One German officer noted, “The waves rose high in the strong wind. The ships tossed hither and thither. Water foamed up over the upper decks. The gun’s crew and ammunition carriers found it difficult to keep their feet.” The rough seas presented more trouble for Cradock and his men than it did for the Germans. Spee conceded that “the British suffered more from the heavy seas than we did.”

Otranto could be of little service to Cradock. Her great size and the short range of her guns made her more of a target than an asset. Her captain realized this and did his best by zigzagging and altering speed in hopes of confusing the enemy. When Gneisenau put two shells over his fore bridge, one 50 yards on his starboard bow and the other 150 yards astern, he drew out of line to the westward and took no further action in the battle.

The fighting continued. The British had difficulty seeing their targets owing to the darkness, while the Germans easily found their marks. The gunnery officer on the Glasgow observed, “No fall of shot could be seen except an occasional common shell bursting short in line with flashes of enemy guns.”

Good Hope and Monmouth engaged Scharnhorst and Geneisenau, while Glasgow exchanged shots with Dresden and Leipzig. Nürnberg was still several miles astern of Spee, but was making her upmost speed to join the fight. The British were missing their targets, while the Germans scored hit after hit.

Two Flaming Heavy Cruisers

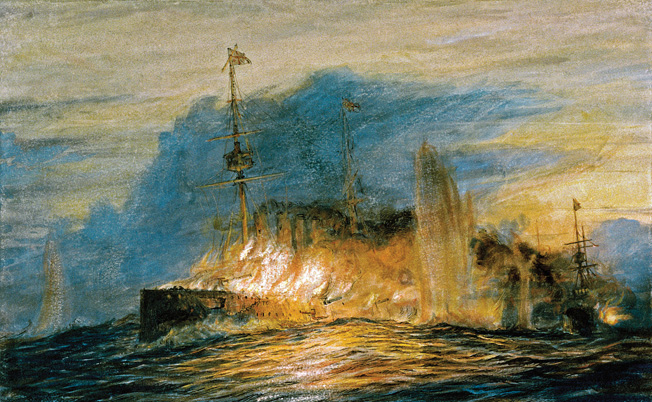

Within minutes after the battle began, a shell hit the forward 9.2-inch gun on Good Hope. The flagship shuddered, and a sheet of flames rose over the vessel. The 9.2-inch gun was knocked out of action. It was a serious blow for the British. A few seconds later, Monmouth was hit on the foredeck; fires broke out on her port side. The heavy cruiser backed out of line and never did get into station.

In short order, an 8.2-inch shell from Scharnhorst hit the British flagship amidships. Fires broke out, and some of the ammunition on board Good Hope exploded. Both British heavy cruisers were now easy targets in the glow of the flames. A third salvo from Scharnhorst hit Good Hope, causing the fires on board to spread. The German heavy cruisers were firing a salvo once every four minutes. By 7:23, the range was down to 6,600 yards. Spee thought Cradock was attempting a torpedo attack. He turned one point eastward.

Cradock reduced the range to bring his 6-inch guns into play. His after 9.2-inch gun was firing once a minute. The British admiral was in dire straits, with ammunition exploding and fires raging below decks. Monmouth was also taking a great deal of punishment. She was ablaze and listing. It was starting to get dark but the fires on the two British heavy cruisers illuminated them, making them perfect targets.

With the range down to a few thousand yards, Good Hope and Monmouth were in position to fire their 6-inch guns, but they missed their targets due to the darkness. Meanwhile, shell after shell continued to hit the two dying ships. Finally, one of Gneisenau’s shells hit Monmouth’s fore-turret, blowing off the roof and setting the housing on fire. Flames broke out, and there was a deafening explosion. When it subsided, both gun and turret were gone. Fires continued to rage on the heavy cruiser. Another shell from Gneisenau struck Monmouth’s side and knifed through the body of the ship near ammunition stored for the starboard guns.

Abandoning the Monmouth

Cradock continued toward the enemy. He was determined to fight against hopeless odds. Range was down to 5,500 yards. Good Hope was in a last desperate effort to sell her life dearly. At 7:53 pm, the fire aboard Good Hope reached the magazine. There was a tremendous explosion; flames reached 200 feet above the deck. The explosion was so great that crewmen aboard Nürnberg, six miles away, were forced to hold their hands over their ears. Good Hope and her entire crew, including the gallant Cradock, went down.

Glasgow was more fortunate. Despite the numerous shells fired at her by Leipzig and Dresden, she was hit only five times. Three shells struck the light cruiser in the coal bunkers without exploding, one hit the conning tower without exploding, and one burst aft above the port propeller, tearing a hole in the side and flooding one of the ship’s compartments.

Captain Luce of Glasgow directed his efforts to assisting Monmouth. The crew of the heavy cruiser managed to extinguish the fires on deck, but other fires were raging below. Luce’s ship was in relatively in good shape, and he hoped to save Monmouth. At 10:15, Luce signaled by Morse lamp, “Are you alright?” The reply was, I want to get stern to sea. I am taking water badly forward.” Luce signaled, “Can you steer north-west? The enemies are following us astern.” There was no answer.

“It was obvious,” wrote one of Glasgow’s officers, “that the Monmouth could neither fight nor fly. She was badly down by the bows, listing to port with the glow of her ignited interior brightening the portholes below her quarterdeck. It was essential that there should be a survivor of the action to turn Canopus which was hurrying at her best speed to join us and, if surprised alone must share the fate of the other ships. Monmouth was therefore reluctantly left to her fate, and when last seen was bravely facing the oncoming enemy. Glasgow increased to full speed and soon left the enemy astern, losing sight of them about 2050.”

In his heart, Luce wanted to stay by Monmouth, but one of his officers pointed out that the enemy was jamming his wireless signals and therefore he could not warn Canopus. It was therefore necessary to leave the stricken cruiser and save the pre-dreadnought. “It was an awful affair to leave the Monmouth, but I don’t see what else the skipper could have done,” concluded the gunnery officer. Glasgow and Otranto fled the scene.

The Disastrous Fate of the Monmouth

Meanwhile, Spee took stock of the situation. He had lost contact with the enemy at 10 o’clock. He did not know that Good Hope had foundered. He signaled his light cruisers: “Both British cruisers severely damaged. One light cruiser apparently was fairly intact. Chase enemy and attack with torpedoes.”

Earlier, Nürnberg had sighted smoke. It was from Glasgow. The German warship chased her, but she disappeared over the horizon. Nürnberg continued her search while sailors began throwing empty cartridge cases overboard. They saw debris, possibly from Good Hope, but thought it was their own cases. They did not report the evidence. Thus, Spee did not know of the British flagship’s demise and attempted no rescue.

Captain Karl von Schonberg of Nürnberg saw a vessel in the darkness but refrained from firing on her. There was the distinct possibility that she might be German. He challenged her but received no answer. In the moonlight, the German captain then realized it was the enemy. One of Spee’s sons, Otto, an officer on Nürnberg, reported: “She [Monmouth] had a list of about ten degrees to the port. As we came nearer she heeled still more, so that she could no longer use her guns on the side turned towards us.”

Schonberg waited to give the enemy a chance to surrender, but her flag was still flying. So reluctantly he opened fire on her. “We opened fire at short range,” wrote Otto von Spee. “It was terrible to have to fire on poor fellows who were no longer able to defend themselves. But their colors were still flying and when we ceased fire for several minutes they did not haul them down. So we ran up for a fresh attack and caused [Monmouth] to capsize by our gunfire.”

Nürnberg continued to fire on the dying Monmouth. The British cruiser rolled over on her side and capsized. At 8:58 pm, the sea closed over her.

Monmouth sank with her flag still flying. Schonberg could not attempt a rescue since the sea was rough and new smoke was seen. He thought it was the enemy, but after steering toward it he realized that it was from the other German warships. By then it was too late for Monmouth. There were no survivors from the doomed heavy cruiser.

“Better to Have Fought and Lost Than Not to Have Fought at All”

The Battle of Coronel was over. The British had lost two heavy cruisers and 1,600 men, while the Germans did not lose a single ship and had only a few men wounded. It was the first British naval defeat since the War of 1812. A German historian boasted: “The Battle of Coronel will ever be memorable in the annals of our Navy. On that day von Spee’s name was enrolled in the list of German heroes. He had materially dimmed the glory of England’s mastery of the sea.”

In Great Britain, there was muted criticism of Cradock. Admiral David Beatty wrote his wife: “He was a gallant fellow, and I am sure put up a gallant fight, but nowadays no amount of dash and gallantry will counterbalance great superiority unless they are commanded by fools. He has paid the penalty, but doubtless it was better to have fought and lost than not to have fought at all.”

It was said that the presence of Canopus might have made a difference. Her 12-inch guns would have added more firepower. But she was too slow to keep up with Cradock. Also the range of Canopus’s guns was more apparent than real. One gunnery officer stated under good conditions the range was only 9,000 yards. The conditions at Coronel allowed only a 4,000-yard range.

Perhaps Cradock’s biggest mistake was taking along Otranto. Saddled with her slow speed, the admiral was unable to cross the German “T.” But the main criticism was directed at the Admiralty for not giving Cradock sufficient force to fight Spee. As Beatty said: “Kit Cradock has gone at Coronel. His death and the loss of the ships and the gallant lives in them can be lid to the door of the incompetency of the Admiralty.”

Spee’s Ultimate Defeat in the Falklands

The Admiralty was determined to make up for the mistake, sending the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible, under the command of Vice Admiral Frederick Doveton Sturdee, to join the South Atlantic squadron. They arrived at the Falkland Islands on December 7 and began coaling. The next day, Spee arrived at the islands to attack, commencing the Battle of the Falklands.

This time the British had superiority of speed and firepower. Spee tried to escape but quickly realized that the British would overtake him. He ordered his light cruisers to scatter while he and his heavy cruisers engaged the British battlecruisers, armed with 12-inch guns. For over three hours, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau exchanged shots with the two British battlecruisers. In the end, both German heavy cruisers were sunk. Scharnhorst went down with her entire crew, including Spee. Gneisenau had only 187 survivors.

Sturdee’s light cruisers chased Spee’s light cruisers. Leipzig and Nürnberg were sunk with great loss of life. Dresden managed to escape. In March of the following year, Dresden was cornered and scuttled by her crew. In November 1914, a few days after Coronel, Emden was caught off Direction Island and sunk by the Australian cruiser Sydney.

Back home in Great Britain, Cradock was regarded as a hero by the rank and file. He had fought bravely against hopeless odds and gone down with his ship. For a seagoing people with a proud naval tradition, that was the ultimate sacrifice.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments