By Dr. Carl H. Marcoux

Although neither side was aware of it at the time, the battle for Okinawa would be the last major battle of World War II.

To the Americans, Okinawa represented a major stepping-stone toward the final defeat of the Japanese Empire. The successful occupation of the island by American forces would provide air bases and naval facilities that would allow for attacks on the Home Islands themselves. To the Japanese, the surrender of a base so close to the heart of the empire would seriously compromise the ability of their armed forces to defend the homeland. Capture of the island would also interdict the critical flow of petroleum to Japan from Borneo, Sumatra, and Burma.

Okinawa is the largest and most densely populated island in the Ryukyu chain, some 380 miles southwest of the Japanese Home Island of Kyushu. With a total area of 485 square miles, Okinawa is approximately 60 miles long with a width of 2 to 18 miles. The island’s northeastern area is very rugged, mountainous, wooded, and lightly populated.

In 1945 the population of Okinawa was estimated to be approximately 500,000, two-thirds of whom lived in the southern one-third of the island. Unlike the north, the south had large open areas suitable for cultivation. Before World War II, the Okinawans maintained a largely rural, agricultural society. The islanders fished and raised sugar cane, sweet potatoes, rice, and soybeans. They tended to concentrate in small villages rather than in large cities. Ancestor worship dominated their religious practices, and the tombs of those ancestors dotted the countryside.

The Japanese on Kyushu regarded the Okinawans as their inferiors. The Okinawans were a blend of Japanese, Malay, and Chinese ancestry. Although they spoke a Japanese dialect, communication between the two groups often remained strained. Okinawan labor provided most of the manpower for the construction of the elaborate system of defenses erected by the Imperial Japanese Army.

Why did the islanders support the Japanese occupiers? First, the Army dealt brutally with anyone failing to cooperate. Second, the Japanese told the Okinawans that rape, torture, and even death would be their fate once they fell into the hands of the American Army. The Japanese Army also did everything it could psychologically to discourage civilians from surrendering to the Americans in the forthcoming campaign. They even advocated suicide by the noncombatants as the alternative to what they considered to be a dishonorable capitulation.

The sudden loss of the Japanese bases in the Marianas—Guam, Saipan, and Tinian—and the destruction of the Japanese 31st Army there in July 1944 necessitated the strengthening of defenses in the Ryukyu island chain, Okinawa in particular. Imperial Headquarters created the 32nd Army, led by three crack divisions—the 9th, 24th, and 62nd—a force that would ultimately consist of over 110,000 men in infantry, artillery, engineers, and communications units, as well as naval and aviation personnel. Included in that number were 24,000 Okinawan males of the Home Guard, conscripted into the 32nd, whether they were willing or not. Some individual Okinawans were incorporated into the veteran Japanese infantry units as well. The original strategy called for defense against any invading force by Japanese air and naval units during the attempted landings, followed by a mop-up by the Japanese infantry of any enemy troops that successfully made landfall.

The Imperial Headquarters in Japan upset this plan early on by transferring the 25,000-man 9th Division from Okinawa to Taiwan. These men could have been used to repel the enemy troops that made it ashore during the initial landings. Moreover, an additional 5,400 men of the 6,000-man contingent of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade were lost when the 6,000-ton transport Toyama Maru was sunk en route from Japan to Okinawa by the American submarine Sturgeon. Only 600 men from the 44th and the Toyama Maru’s crew survived the attack. The Japanese High Command was then forced to reconstitute the 44th Mixed Brigade with the addition of local draftees and other miscellaneous reserve personnel.

The Imperial High Command also promised the Okinawa defenders heavy support from squadrons of kamikaze planes and ships to disrupt the landings. Kamikaze pilots, successfully used in the defense of the Philippines, would crash their aircraft into the decks of the American ships. Small one-man submarines and torpedo boats, some 700 in number and stationed at islands within the Ryukyu chain, would also be employed to attack the incoming Americans. Once the American fleet had been decimated by Japanese air and sea forces, and the newly landed American troops were deprived of the necessary logistical support, the 32nd Army would begin a counterattack against the invaders.

According to the 32nd Army’s senior staff officer in charge of operations, Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, the reduction in available ground troops, such as the 9th Division, required a major revision of the initial plans. Instead of meeting the invaders as they landed on the beaches and defending the airstrips in the beach areas, the Japanese forces elected to dig in on the south end of the island and destroy the invaders as they moved south against the heavily fortified island installations. These static defenses came to be known as the Naha-Shuri-Yonabaru Line, stretching from the island capital, Naha, on the west coast, to Yonabaru, a port city on the island’s east coast.

The Japanese defense plan called for the creation of a series of strongpoints along a number of ridges and escarpments that surrounded the ancient walled city dominated by Shuri Castle. Concentric rings of fire zones permitted the defenders at the strongpoints to protect one another from the advancing Americans. All defensive positions were heavily fortified and contained deep subterranean excavations to protect the troops from enemy bombardment. The Japanese 62nd Division faced the Americans at Shuri. The 24th Division, remnants of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade, and miscellaneous Japanese naval units backed up the 62nd behind the Shuri Line.

Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima arrived on Okinawa on August 11, 1944, to assume command of the Japanese forces. It was his method of operation to depend on the recommendations of his subordinates in carrying out the mechanics of the island’s defenses, although he took full responsibility for them. This lack of direct involvement in tactical planning was quite common among the senior officers of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Major General Isamu Cho, Ushijima’s chief of staff, practiced no such detachment. Cho had the reputation of being tough, decisive, aggressive, and forceful. He would demonstrate these qualities as the battle for the island proceeded.

Over 1,600 Ships Carrying 500,000 Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines Along with Their Weapons and Supplies Headed for Okinawa

Colonel Yahara provided the overall strategic plan for the Imperial Army’s defense of Okinawa. Conservative and pragmatic, he chose to organize the Japanese Army into a defensive posture, ensuring that the Americans would pay the maximum price in their attempts to unseat the island’s defenders. Yahara had to curb the impetuous General Cho, who sought to persuade Ushijima to launch an offensive campaign.

The preparation of the invading American forces would prove to be the most comprehensive in their history. Over 1,600 ships carrying 500,000 soldiers, sailors, and Marines along with their weapons and supplies headed for Okinawa prior to April 1945 from the Philippine Mariana and Caroline Islands as well as the continental United States. The bulk of the attackers had to cross almost 8,000 miles of ocean to arrive at their destination.

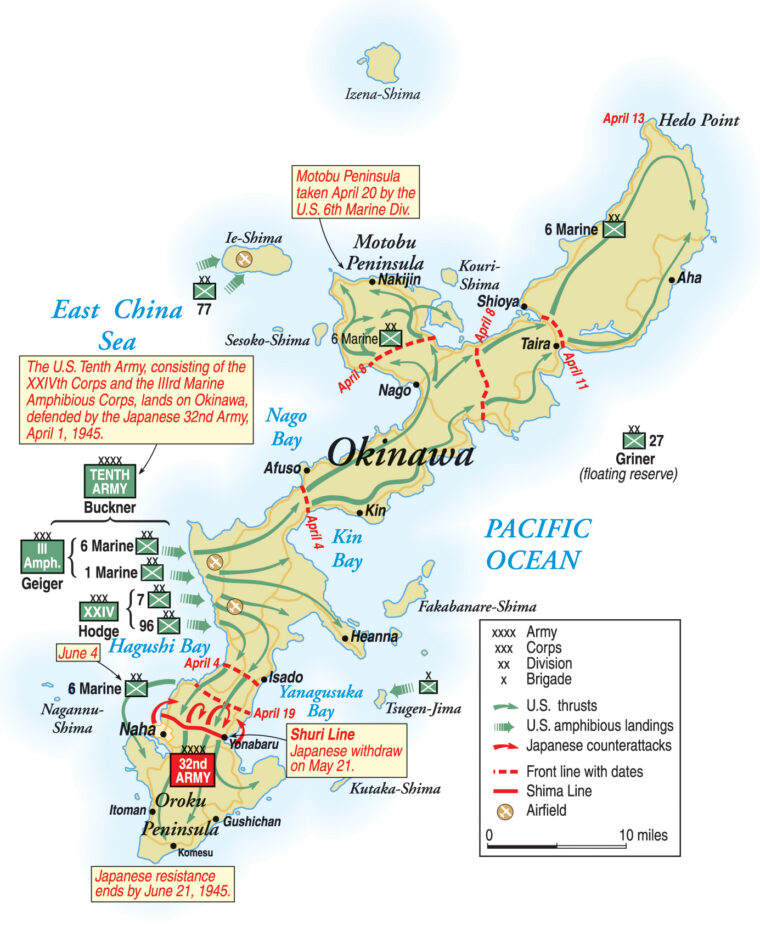

Operation Iceberg, as the Okinawan invasion came to be called, lay under the overall direction of Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Ocean Area (POA), headquartered in Hawaii. His main striking force for the invasion would be the 5th Fleet’s Task Force 58, commanded by Admiral Raymond Spruance. Aircraft carriers and their support vessels dominated the task force. The tactics for the invasion itself called for two groups: the Covering Force of two fast carrier task groups—one American and one British under Admiral Bruce Fraser—and the Joint Expeditionary Force, which included all of the naval elements and ground troops directly involved in the landings. Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner would be in direct command of the amphibious forces making the landings.

Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner would command the invading force ashore. Designated as the Tenth Army, it consisted of the XXIV Corps of the U.S. Army, which included the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions and the III Marine Amphibious Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Roy G. Geiger. Geiger’s corps consisted of the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, with the 2nd Marine Division held in reserve.

Buckner also had the 27th and 77th Infantry Divisions available in reserve. The American general thus commanded a landing force larger than the one employed in the Normandy invasion the previous year. Over 180,000 soldiers and Marines would be going ashore.

The American master plan called for a landing in force at the Hagushi Bay beaches in west-central Okinawa, followed by a drive across the island’s narrow center. This action would be followed by a sweep both north and south from the center. The invaders also planned to seize the vital Yontan and Kadena Airfields close to the initial landing area as quickly as possible.

Prior to the invasion of Okinawa itself, Admiral Turner ordered an American strike force to seize a group of islands, the Keramas, off Okinawa’s southwest coast, as well as a small adjacent group called the Keise Shimas. The Keramas contained a substantial anchorage, which would prove to be an ideal facility for ships, either those waiting to unload off the Okinawan beaches or those that were damaged by the kamikaze attacks during the landings. A bonus for the Americans was the discovery of a large flotilla of suicide motor boats that the Japanese planned to use against the U.S. fleet.

D-day was set for April 1, 1945, and a colossal shelling of the Hagushi beach preceded the movement ashore by the Army and Marine assault troops. Carrier planes swooped down to strafe the beaches where the Americans were to land. The tremendous barrage and air attack accomplished virtually nothing as far as the Japanese were concerned, for General Ushijima had the majority of his troops safely hidden away in the caves and tunnels of the Naha-Shuri-Yonabaru Line.

The Marines of the III Amphibious Corps moved north after landing; the Army’s XXIV Corps headed south. Initially, neither the Army nor the Marine contingents encountered any meaningful opposition. Some Okinawan Home Guard draftees had been stationed at the island’s midpoint, but they quickly gave way and retreated when confronted by the Americans. The 1st Marine Division quickly crossed the island’s narrow Ishikawa isthmus, cutting off any direct communication between the Japanese defenders north and south of the incursion.

The 6th Marine Division, under Maj. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, headed north, moving to the mouth of the Motobu Peninsula without encountering any meaningful resistance. There, they faced formidable resistance from Colonel Takehiko Udo and his 3,000-man 2nd Infantry Unit of the reconstituted 44th Brigade, well dug in on Mount Yae Taki. It took the 6th, aided by heavy bombardment from naval vessels offshore as well as supporting air strikes, almost three weeks to secure the island’s northernmost reaches, leaving only the heavily entrenched Japanese forces in the island’s south to combat.

Meanwhile, Japanese Admiral Matome Ugaki had launched his air attacks against the American shipping anchored at Hagushi Bay. These attacks were an essential part of the Japanese strategy to defeat the invading American forces. Ugaki had over 3,000 planes, both conventional and kamikaze, under his command. At the close of Easter week, some 700 planes took off from Kyushu and Taiwan to raid Hagushi.

Known as Operation Ten-Go, Ugaki’s plan was to disrupt American shipping and prevent it from providing the necessary fire support, arms, and equipment to the Tenth Army ashore. Ugaki called the scheduled aerial strikes kikusui or “Floating Chrysanthemums.”

The American ships and aircraft fought the Japanese pilots with every means at their disposal, but defense proved difficult when an enemy flyer was prepared to commit suicide by diving his aircraft into his target. In their initial mass attack, the Japanese sank eight ships and damaged another 10.

Throughout the battle for Okinawa, the Japanese, employing their kikusui tactics, conducted some 10 massed kamikaze attacks and nearly 900 separate air raids against American forces. Japanese air strength was totally destroyed in the attacks, including approximately 1,900 kamikazes. In total, the Japanese sank 36 American ships and damaged an additional 368.

The loss of two particular ammunition ships to the kamikazes did temporarily impede the movement of Buckner’s forces in their attempt to dislodge the enemy ashore. The Hobbs Victory and the Logan Victory, sunk during these raids, carried the phosphorus incendiary shells and 81mm mortar rounds needed to flush the Japanese defenders from their defensive cave positions.

In response to the Japanese air attacks, Admiral Spruance ordered Vice Admiral Marc C. Mitscher and his Task Force 58 carrier air group to strike Japanese airfields on Kyushu. These attacks were designed to reduce the pressure of the kamikaze attacks on American shipping. Admiral Nimitz, from his Honolulu headquarters, also prevailed on the U.S. Army Air Forces to employ heavy B-29 bombers to carry out the same mission. The damage caused to the aircraft parked on Japanese airfields reduced to some degree the kamikaze threat to the American fleet stationed off Okinawa.

In Successive Waves the American Aircraft Torpedoed, Bombed, and Strafed the Yamato and Its Accompanying Cruiser and Destroyers.

In a vain effort to support the Japanese defenders, the Imperial Navy dispatched the cream of its remaining fleet, headed by the super battleship Yamato, to aid in the island’s defense. On April 6, the Yamato, accompanied by the cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers, steamed out of Tokyo Bay, bound for Okinawa.

The Japanese flotilla lacked air cover. American submarines cruising off the Japanese coast quickly spotted the task force and reported its position to Admiral Mitscher. The following morning the American admiral sent a huge force of aircraft to attack the Yamato and its consorts. In successive waves the American aircraft torpedoed, bombed, and strafed the battleship and its accompanying cruiser and destroyers. In a few hours, the Yamato, the Yahagi, and four of the eight destroyers were sunk. So ended any real attempt by the Japanese Navy’s surface vessels to aid in Okinawa’s defense.

The drive to Okinawa’s south, spearheaded by the XXIV Corps’ 7th and 96th Divisions, quickly encountered strong resistance, for it was here that the bulk of General Ushijima’s 32nd Army troops awaited the American attack. On April 4, the 7th and 96th reached the Naha-Shuri-Yonabaru Line. In a three-day attack lasting from April 9-12, they attempted a direct frontal assault against a key Japanese strongpoint, the Kakazu Ridge. The Americans lost 22 of the 30 tanks committed to the attack. Failure to provide infantry support for the vehicles permitted Japanese suicide squads to move in and disable the tanks with satchel charges.

The Americans were repulsed in this attempt by determined resistance, operating from well- protected firing positions. It soon became apparent that direct frontal assaults against the Japanese defense line would prove to be expensive in terms of men, supplies, and equipment.

The Imperial Japanese Army’s defenses consisted of more than a line, of course. The defenders had utilized every hill, escarpment, and ravine in front of Shuri Castle for some 31/2 miles to forestall the American advance. General Ushijima had his men dig far down into the earth, fashioning a series of tunnels, caves, and foxholes impervious to shelling by the heavy weaponry of the American naval forces lying off the island’s coast. The 32nd Army had a formidable supply of weapons of its own—heavy artillery, mortars, and machine guns—to reinforce its defensive positions. It used huge 320mm mortars against the advancing Americans with deadly effectiveness.

Moreover, the rugged terrain precluded the successful use of American armor in many locales. Japanese maps captured during the battle convinced the American commanders that the Shuri defenses were the strongest yet encountered in the Pacific. Another tactic that proved productive for the Japanese was the stationing of their defensive positions on the reverse slopes of the hills they defended. From these positions they could lob heavy mortar shells on the Americans advancing up the face of the hill as well as targeting their enemy as they came over the crests.

General Cho, greatly heartened by the accomplishments of the 32nd Army in repulsing the Americans during their initial drive against the Shuri Line, prevailed on his commander, General Ushijima, to launch a counterattack. Colonel Yahara, Ushijima’s senior staff officer and a proponent of defensive warfare, argued against such a move, but General Cho succeeded in winning his point with Ushijima.

On April 12, the Japanese 24th Division, together with the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade and the 272nd Independent Infantry Battalion of the 62nd Division, attacked the American positions facing the Naha-Shuri-Yonabaru Line. The Japanese failed to break through and lost over 1,500 men in the effort. The destruction of these front-line troops ultimately reduced the ability of the Japanese to maintain their existing defensive positions.

Cho’s ill-conceived plan conflicted with the original Japanese strategy to assume a fixed defensive position and thus maximize the losses to American forces trying to break through. As Colonel Yahara foresaw, when holed up in caves on the reverse slopes of ridges and escarpments the Japanese defenses cost the Americans dearly. But outside the caves, on the attack, the Japanese lost their tactical advantage and suffered extensive losses when exposed to the American heavy artillery, mortar, and naval gunfire.

On April 18, General John R. Hodge’s 7th and 96th Divisions, now strengthened by the addition of the 27th on their right, or western, flank, renewed their attack on the Japanese fixed defenses. Again, the forward progress of Hodge’s troops was stopped with little gain, the Americans sustaining 750 casualties in this second unsuccessful attempt.

The 27th sustained more losses than any other American division during that frontal assault. Moreover, it had not been at full strength when it had arrived on Okinawa. Buckner also had at his disposal the III Marine Amphibious Corps, now that the Marines had completed their other assignments in the island’s north. Buckner’s failure to employ these experienced Marine divisions instead of depending on the less well trained and shorthanded 27th can only be ascribed, according to Marine historian Robert Leckie, to the general’s desire to have Army troops credited with defeating the Japanese. Nevertheless, the Americans persisted in their frontal attacks against Japanese fixed emplacements. For the next five days, in hand-to-hand fighting, they attacked the Japanese entrenchments and stormed and captured the Kakazu Ridge. Finally, on the night of April 23, with the northernmost positions of his Naha-Shuri-Yonabaru Line breached in a number of key areas, General Ushijima retreated to his next line of defense.

On May 1, General Buckner substituted the 1st Marine Division for the battered Army 27th. He reassigned the latter to security duty in the occupied northern portion of the island for the balance of the campaign. The 96th Division was replaced by the 77th, available after completion of the takeover, in a bloody battle, of the smaller Ie-Shima Island to the north. Buckner also planned to substitute the 96th for the 7th, after the former had been rested and brought up to full strength.

The Total Japanese Losses in Their Fruitless Counterattack Reached 6,227 Dead.

General Cho had not given up his conviction that a forceful counterattack would blunt the American advance. He pointed out that now the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions would be thrown into the fight by the Americans. Once more, Cho convinced General Ushijima to authorize another even more complicated strike against the American positions. In addition to the direct frontal assault on American lines, Japanese troops would also utilize small boats launched from Naha to land troops behind them at night. At the same time, a powerful kamikaze attack against American naval units would be undertaken to turn attention away from the land offensive. Ushijima acquiesced to the plan.

On May 3, the second counterattack began. The Japanese 24th Division, charged with breaking through the American positions with a direct frontal assault, took a fearful beating. The Japanese failed to make any meaningful penetration of American positions, and their efforts to land infiltrators behind American lines by boat met the same fate. By May 5, it became clear to General Ushijima that the offensive had failed. The total Japanese losses in this fruitless counterattack reached 6,227 dead.

Seeing an opportunity to exploit these losses, Buckner’s subordinates now urged him to approve a landing by either Army or Marine units on beaches behind the Japanese defensive lines at Minatoga, a port on the island’s south end. Pressure also came from Admiral Turner who wanted Okinawa quickly won to reduce the attrition being suffered by his naval units off Hagushi Bay. Marine Maj. Gen. Lemuel Shepard urged the use of the 2nd Marine Division. The Marine general pointed out that the 2nd could undertake a month’s operations with the supplies, both food and ammunition, that it had on hand.

Buckner continued to refuse the recommendations for the establishment of a second front, citing a continuing shortage of ammunition, the difficult reef conditions at possible landing sites in the Minatoga area, and a concern for the strength of the Japanese forces still protecting the beaches there. He continued to press forward against the still strongly defended Shuri Line.

The III Amphibious Corps, consisting of the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, occupied the right, or western, flank of the American position, while the Army’s XXIV Corps, consisting of the 77th and 96th Infantry Divisions, held the left, or eastern, flank. Buckner’s plan called for the two corps to swing in from both coasts, flanking the Japanese positions.

The battle broke down into a series of individual attacks by the Americans similar to the Kakazu action in which the Japanese had to be destroyed in each of their heavily fortified bunkers and caves by infantrymen attacking directly, aided by the use of flamethrowers and satchel charges. Neither heavy artillery from naval forces nor bombing could accomplish the task.

The 6th Marine Division sought to turn Ushijima’s flank on the west by fording the Asa River and crossing the Kokuba Hills into the Kokuba Valley. The 1st Marine Division, operating east of the 6th, planned a direct assault on Shuri itself. They faced Dakeshi and Wana Ridges as their initial targets.

The Army’s 77th Infantry Division opened up its drive to the south with an attack on the Japanese lines in the center of the island. Facing them were two fortified positions, one called Chocolate Drop, covered by fire from the other, Flattop Hill.

Finally, the 96th Infantry Division, occupying the extreme eastern wing of Buckner’s attacks, planned to break the Japanese flank that ran from Yonabaru. There they would be forced to take Conical Hill, protected by the Japanese 89th and 22nd Infantry Regiments. The Dick-Oboe Hill complex, also a critical target, lay ahead on the boundary between the two American Army divisions.

When the 6th Marine Division moved south to encircle the Shuri bastion, it encountered a well-defended position, Sugar Loaf Hill, protected on each side by Horseshoe and Half Moon Hills. On May 17, in a desperate struggle, the Marines took the three positions at the cost of 2,662 casualties.

The 1st Marine Division encountered the same type of resistance in its attacks on Dakeshi Ridge, Wana Ridge, and Wana Draw. There they had the support of tanks, protected by infantry this time, and heavy bombardment from naval units offshore. The Navy fired a half-million rounds into the disputed area even though the ships themselves were under constant threat from kamikaze attacks. On May 21, the 1st finally achieved its objective, but like the 6th, at heavy cost.

The 77th Division, charged with the capture of Chocolate Drop and Flattop, made slow progress. It took over a week to secure Flattop and several days after that to wipe out all resistance in isolated caves. The Chocolate Drop bastion fell to the 77th on May 21.

It was the 96th Division, operating along Buckner Bay, that finally broke the Shuri Line. The capture of Conical Hill opened up the city of Yonabaru to the Americans and allowed them to spill out into southern Okinawa. Attempts to completely encircle the Japanese positions around Shuri itself failed, though, due to the commencement of heavy rains that seriously impeded any progress along the front.

The Japanese High Command realized that continued resistance at Shuri would result in ultimate destruction despite their fanatical resistance. American staff officers believed that their opponents would remain at Shuri and fight to the bitter end. The Japanese had actually begun plans for the evacuation from their now untenable position before they found themselves surrounded. The continuous hard rains and overcast hid to some degree the Japanese withdrawal.

Japanese Directives Called for the Execution of all 100,000 Allied POWs Once Japan was Invaded.

On May 22, the Japanese began their retreat. First they began to move their supplies and wounded. The new command post for the 32nd Army would be established on Hill 89 at Mabuni on the island’s southernmost coast. By May 28, the bulk of the Japanese defenders had evacuated the Shuri area, leaving only rearguard elements to slow the advance of the American forces. Later, the American commanders admitted that Ushijima’s retreat, despite substantial losses, had proven to be an impressive military operation. Unfortunately, those civilians that chose to accompany the Japanese troops paid a heavy price in terms of both injury and death.

By June 3-4, the Japanese established their final defensive position toward the southern tip of the island on the Yaeju-Dake Escarpment. A separate smaller segment, mostly naval troops, held positions on the Oroku Peninsula to the northwest of the newly established Yaeju-Dake defenses. The Navy men held out for 10 days before being overwhelmed by the 1st Marine Division. The Japanese commander, Admiral Minoru Ota, committed suicide along with his immediate staff.

At Yaeju-Dake, improved weather permitted more extensive employment of flamethrower tanks and satchel charges against the entrenched Japanese. On June 18, General Buckner, standing at a forward observation post, was wounded when a Japanese shell blew up a coral formation near him and a piece of the coral was driven into his chest. He died 10 minutes later. Marine General Geiger assumed overall command.

Finally, on June 21, formal Japanese resistance ended. For the first time in the Pacific War, substantial numbers of soldiers surrendered rather than continuing a hopeless fight. Not so Generals Ushijima and Cho. Together they committed hara-kiri, ritual Japanese suicide, on the heights of Mabuni overlooking the ocean, at 4 am on June 22. The fighting for the island ended after 82 days.

Total American casualties during the Okinawa campaign numbered 49,151. Deaths numbered 12,427, with 4,907 Navy, 4,582 Army, and 2,938 Marine personnel paying the ultimate price. Japanese deaths alone reached 110,000. The 32nd Army was virtually destroyed. In addition, some 160,000 Okinawan civilians perished in the conflict.

What did the Okinawa victory gain for the Allies? First, it provided them with a base only 380 miles from the Japanese Home Islands. From this close proximity to the heart of the Japanese Empire, multiple attacks by land, sea, and air could be launched in the anticipated invasion of Japan proper. The war could be brought home forcefully to the enemy in a matter of a few short months.

For the Japanese, defeat on Okinawa had been costly. They were now at the mercy of an increasingly powerful enemy at their doorstep. They had lost over 70,000 of their veteran front-line troops, plus the balance of their Navy and at least 20 percent of their remaining military aircraft.

The Allies experienced a preview of the fanatical determination of the Japanese, both military and civilian, to defend their Home Islands against the anticipated invasion. In the battle for Ie-Shima and elsewhere on Okinawa itself, female civilians donned uniforms and fought to the death alongside their male counterparts. Preliminary estimates of initial Allied losses in landings to be made on Kyushu were as high as 100,000. Japanese civilians had formed home defense units, often armed with nothing more than bamboo spears, and had pledged to fight until death. The ultimate subjugation of the Japanese Empire could cost in excess of a million lives to both sides.

Of further concern to the Americans would be the fate of the 100,000 Allied prisoners in Japanese hands. Japanese directives called for their execution once Japan was invaded. A protracted invasion effort would certainly result in the deaths of most of the prisoners.

The experiences of the Okinawa campaign weighed heavily on both the military and civilian leadership in the United States. Certainly the potential losses that would occur if an invasion of the Home Islands were to come about bore directly on President Harry Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Dr. Carl H. Marcoux is a resident of Newport Beach, California, and a World War II veteran of the U.S. Merchant Marine.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments