By Robert Barr Smith

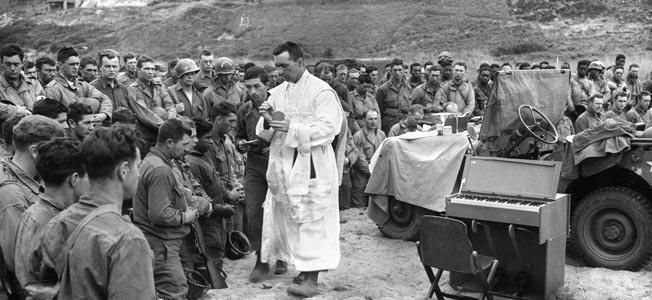

They carried no weapons, only holy books and rudimentary vestments, a crucifix or a Star of David and sometimes a little Communion kit. But they were towering figures on the battlefield, symbols of something eternally good in a pitiless world of cruelty, horror, and death. In two cataclysmic world wars, American and British military chaplains served everywhere the armies and navies went, bringing peace where there was no peace and security where there was no security.

When World War I ended in 1918, a total of 2,363 chaplains had seen yeoman’s service with the United States Army. Father Francis Duffy, senior chaplain to the 42nd Division, drew crowds of soldiers who were waiting for him to hear confessions aboard a transport bound for France. In action, Duffy was always near the heaviest fighting, often going to the forward dressing station of one of the division’s units. He ended the war with both the Distinguished Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal.

“Live With the Men, Go Everywhere They Go”

The British chaplaincy had been established by royal warrant in 1796. During World War I, some 172 British chaplains were casualties. Thousands of British soldiers remembered Chaplain Studdert Kennedy, a tiny Irishman whom the soldiers called Woodbine Willie for his habit of passing out Woodbine cigarettes in the trenches. Kennedy’s personal philosophy spoke for all the chaplains of that war: “Live with the men, go everywhere they go. Make up your mind you will share all their risks, and more, if you can do any good. The line is the key to the whole business. Work in the very front and they will listen to you. Take a box of fags in your haversack, and a great deal of love in your heart and go up to them; laugh with them, joke with them. You can pray with them sometimes, but pray for them always!”

During the war, three British chaplains received the Victoria Cross and dozens more were awarded other decorations. Courage seemed to run in their bloodlines. Throughout the bitter fighting in France in April 1918, British chaplain Theodore Bayley Hardy repeatedly went out under heavy fire to pull wounded men to safety, “absolutely regardless,” as the official description put it, “of his personal safety.” Rescuing wounded soldiers as far as 400 yards in front of British positions, and as close as 10 yards to a German pillbox, Hardy personally received the Victoria Cross from King George V, who appointed Hardy his own royal minister in the hope of keeping the chaplain off the battlefield. That proved impossible. Hardy had already received the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross, making him the most decorated noncombatant in the war. By mid-October, he was back with his beloved soldiers, and he was fatally wounded by German machine-gun fire at Rouen.

In March 1916, Chaplain Edward Mellish prowled the shell-swept ground between captured German trenches. On the first day he brought in 12 badly wounded men under fire so heavy that three of the wounded were killed before he could get them to safety. On the second day, Mellish got 12 more, and on the third night he took a party of volunteers out to recover anyone who remained. A British officer wrote later that Mellish “walked out into a tempest of fire with a prayer book under his arm as though he was going to a church parade in peacetime.” That same year, in Mesopotamia, Reverend W.R.F. Addison received the Victoria Cross for similarly rescuing wounded men under heavy fire, carrying one man to safety on his back.

Chaplains in World War II: From 169 to 3,700

The British padres responded to fire with extraordinary heroism. The peacetime establishment of 169 service chaplains grew in number to 3,700 before the war ended. After France fell to the onrushing Nazis in 1940, some 50 British chaplains passed into German captivity, where they carried on their ministries. Many prisoners were helped by the optimistic faith of the imprisoned chaplains. Years after the war, one chaplain was stopped on the street in Edinburgh, Scotland, by a man who had been a fellow POW. He had never forgotten, said the man, that in the depths of his own depression, the chaplain had called to him, “Cheer up, boy, God will do his stuff yet.”

Senior commanders knew well the powerful force of the spiritual. British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery once observed that “battles are won primarily in the hearts of men. The most important people in the Army are the nursing sisters and the padres—the sisters because they tell the men they matter to us, and the padres because they tell the men they matter to God. And it is the men who matter.”

The Italian Campaign

During the assault crossing of the Rapido River in Italy in 1943, Reverend Ronald Edwards drove his jeep down to the river with machine-gun bullets spattering all around him. Edwards stopped, got out, and waved a Red Cross flag, which did nothing to deter the German fire. Undaunted, Edwards loaded wounded men into his jeep and drove them to safety. Returning to the river bank, he stripped off his vestments and swam across the river to minister to wounded men on the far bank. He managed to bring back some of the hurt men, along the way helping to clear assault boats that were obstructing movement across the river.

During that same Italian campaign, Chaplain Paul Wansey drove his jeep casually into the open to rescue four badly wounded men. Even though stretcher-bearers had been unable to reach the men, Wansey managed to do so, receiving the Military Cross for his service. Then there was Reverend John R. Brookes, somewhat irreverently known as “Dolly.” An infantry platoon leader in World War I, Brookes was now a priest with the Irish Guards. He was “very much the old-style officer of the brigade,” noted one veteran, “tall, slim and immensely elegant.” He was also, said the man, “very jolly and an excellent companion.”

Brookes, who was awarded a Military Cross during the fighting in Italy, knew the hearts of his military parishioners. “A priest,” he said, “must show himself to the troops to be not only their chaplain but their friend. The closer men get to the battlefield the more they desire the help and consolation of their religion, not out of fear or cowardice, but because they have come in contact with reality and what they need is a clear conscience and peace of mind.”

Chaplains in the Airborne

After the epic fight of the British Airborne at Arnhem—the controversial “bridge too far” in World War II history—those troopers who could do so escaped by night across the Rhine. Some were wounded so badly that they could not move. Reverend R. Talbot Watkins, chaplain to the Airborne, helped 50 badly hurt soldiers to an assault boat, then returned to the east bank to look for more. He found none, but remained in hiding on the German bank throughout the next day, swimming back to safety the following night.

Other chaplains also brought survivors back across the Rhine. Three were captured, two with wounds, the third with a jump injury. Seven others, physically able to escape, volunteered to remain behind with the wounded who could not be moved. Reverend Selwyn Thorne, chaplain to an Airborne light artillery regiment, spent all of his time during the fighting at the gunners’ aid station, where nobody could move inside the house except by walking on stretcher handles laid above the wounded. He fed and comforted the injured, buried the dead, and prayed with the living. In the end, Thorne passed into captivity with the survivors.

Reverend Father Daniel McGowan engaged in a most unchaplain-like plan to aid the Dutch Resistance, which had helped the paratroopers at Arnhem in every way they could. McGowan solemnly left St. Elizabeth’s hospital in Arnhem following two shrouded stretchers, reverently reading from his missal. The two blanket-covered “corpses” were in fact a machine gun, three Bren guns, grenades, and a load of ammunition.

Another chaplain, Reverend J.F. McLuskey, a Military Cross recipient, dropped far behind German lines with his SAS parish to work with the French Resistance. He jumped unarmed, as all chaplains did, but carried a substantial load in addition to his rations and other equipment. In his pack were prayer books, hymnals, New Testaments, an oak cross, Communion vessels, and a silk altar cloth dyed Airborne maroon. McLuskey held regular services, although the volume of the men’s hymn-singing sometimes had to be muffled to avoid attracting the interest of a nearby enemy. Other chaplains jumped on D-Day. In a single British airborne brigade, two chaplains were killed and a third captured.

America’s Chaplains in World War II

American chaplains played an equally large role in World War II. Some 9,000 chaplains served with the U.S. Army and still more with the Navy; many of them died helping others. Some 478 American chaplains became casualties—either dead, wounded, missing, or taken prisoner. As a percentage of the number of chaplains on active duty, the number killed in action was exceeded only by the dead of the infantry and air force.

American chaplains’ heroism began at Pearl Harbor. The men aboard the stricken USS Oklahoma would long remember young chaplain Aloysius Schmitt. As water poured into a compartment, Schmitt boosted man after man through a porthole, the only exit from the deathtrap in which they found themselves. When all were clear, Schmitt tried to squeeze through the porthole, but could not, even with sailors pulling from the outside.

“Save yourselves,” said the chaplain; “you are endangering your lives.” “Chaplain,” said one sailor, “if you go back in there, you’ll never come out.” “Please let go of me,” said Schmitt, “and may God bless you all.” Sliding back into the compartment, he went on boosting sailors through the porthole as more desperate men crowded into the flooding compartment. At last, there were no more men to help—only water and darkness in the compartment. The chaplain was gone. Several months later, in a distinctly ecumenical tribute, a survivor of the Oklahoma, a Jewish sailor, spoke warmly of the heroic Catholic to a Protestant congregation. The Navy remembered, too: USS Schmitt, a destroyer, would keep the chaplain’s name alive.

In Japanese Captivity

On Bataan, as American forces fell back toward the south and inevitable surrender, chaplains ministered to both civilians and soldiers in spite of heavy fire and starvation rations. As Japanese bombs crashed into a military hospital, Reverend William Cummings stood calmly among the terrified patients. “All right, boys, everything’s all right,” he said. “Just stay quietly in bed or on the floor.” He invited the patients to pray with him.

Calm descended on the ward as the men joined Cummings in prayer. At last, his elbow and arm broken by a bomb, Cummings turned to another chaplain. “All right, partner, take over,” he said. “I’m wounded.” Cummings would continue his ministry throughout the long captivity, giving to others until he went down with a torpedoed Japanese prison ship. Chaplain Joe LaFleur, on another Japanese Hell Ship, also died helping other prisoners out of the holds of the torpedoed vessel while sadistic guards sprayed the helpless prisoners with gunfire.

Of the 33 chaplains confined at various times in the notorious Cabanatuan Camp No. 1 in the Philippines, only 15 survived the war. Some, like LaFleur, died in sinking prison ships—unmarked, in violation of the Geneva Conventions; others died of malnutrition, disease, and endemic Japanese brutality. Still more were permanently injured, like Chaplain Alfred Oliver, who had his neck broken by a rifle butt when he would not give information to a brutal guard.

Captured British chaplains carried on as well. Australian Chaplain Harry Thorpe spent two and a half years on the notorious “Death Railway” across Siam. Happy Harry, as the prisoners called the ever-optimistic Thorpe, ministered to British, Australian Dutch and American prisoners alike. Sometimes, the suspicious Japanese would permit services; often they would not. At such times, Thorpe and his fellow chaplains held services in the dark, in silence, holding Communion using pomelo grapefruit juice instead of wine and rice bread in place of wafers.

Sometimes the chaplains’ efforts came to bitter ends. In the autumn of 1942, Chaplain Lewis Bryan was forced to watch the execution of four young soldiers who had tried to escape. Bryan shook hands with each of the men and gave them absolution. One of the doomed men told him, “I have my New Testament here, sir, and I am going to read it while they shoot me.” All four soldiers refused blindfolds and died looking the Japanese in the eye.

Frank Kelly and Malcolmb MacQueen

Always ready to pray with any fighting man, the chaplains’ religious denominations, so important in civilian life, ceased to matter. Correspondent Robert Sherrod wrote about Frank Kelly, a Catholic, and Malcomb MacQueen, a Baptist. Kelly was as popular with the Protestants as MacQueen was with Catholics, Sherrod wrote. “Denominational distinctions did not mean much to men about to offer up their lives” on bloody Tarawa.

The popularity of Kelly and MacQueen reflected a growing ecumenical spirit, for most chaplains considered anybody in uniform a member of their parish. Catholic chaplains led Protestant services and presided over Seder services for Jewish soldiers. Jews and Protestants were taught to lead the rosary for Catholic soldiers and often administered last rites. A Protestant chaplain aboard a transport bound for England held 15 Catholic services and three Jewish services. On another transport, short the requisite number of Jewish soldiers required for services, Catholic soldiers volunteered to make up the number. In return, the Jewish men appeared at the rosary benediction.

Prayers on Tarawa

Father John V. Loughlin, chaplain to the Marines on Tarawa, was sought out by Colonel David Shoup, later commandant of the Marine Corps, a Protestant who had been the architect of the landing. “Padre,” said Shoup, “I want you to pray for me.” “What sort of prayer, Colonel?” asked Kelly. Shoup spoke for every officer who has ever led men into combat. “I want you to pray that I don’t make any mistakes out on that beach,” he said. “No wrong decisions that will cost any of those boys an arm or a leg or a hand, much less a life. I want you to pray for that, Padre.”

Loughlin did as he was asked, then spent the first day of the bloody Tarawa assault in a landing craft loaded with medical personnel and critical medical supplies. When the boat stranded on a reef and was hammered by enemy fire, Loughlin hauled wounded Marines out of the water, comforting and praying for them. Later, he slogged through the water under heavy fire to carry medical supplies to the beach, where he remained, ministering to the wounded, giving last rites and collecting the dead.

“I Got Shot in the Ass/In Kasserine Pass”

Protestant chaplain Orville Lorenz won a Silver Star during the Kasserine Pass debacle in North Africa, running through German artillery fire to reach a wounded man far ahead of American lines. Knocked down twice by near-misses, Lorenz reached the man, only to find that the soldier was too badly hurt to move. Undeterred, Lorenz ran back through the same heavy fire, found medical personnel, and led them through the German barrage back to the hurt soldier, then back again through the artillery to the aid station.

During the Tunisian fighting, Chaplain Eugene Daniel stayed behind retreating American forces to minister to both American and German wounded. His courage earned him the Distinguished Service Cross to add to his Silver Star, as well as a letter of praise from the German commander who presided over his imprisonment. Lorenz would spend the next 26 months as a POW.

The pain and fear of war had some lighter moments. Chaplain L. Berkeley Kines survived a sniper’s bullet in the rump during the Kasserine fighting. He would never hear the end of it, as a fellow chaplain commemorated the event in verse: “Poor Berk fell hard and wounded, alas,/ For he got shot in Kasserine Pass.” Even Kines could see the humor, and responded with his own memorable couplet: “I got shot in the ass/ In Kasserine Pass.”

Chaplains of the Navy

Sometimes heroism under fire took simple forms. Navy Chaplain Francis J. Keenan, coming ashore during the Sicily invasion, was burying a soldier killed on the beach when German aircraft attacked. His arms and legs torn by fragments, Keenan went on methodically digging, while soldiers yelled to him to take cover. Keenan worked until he was satisfied with the grave, then read the burial service over the soldier’s remains. Only then did he seek medical aid for himself.

No one in the United States Navy will ever forget the chaplains of the troopship Dorchester, torpedoed in early 1943 in the Atlantic between Labrador and Greenland. The German submarine U-223 put a torpedo into Dorchester early on the morning of February 3, and she sank rapidly by the bow. As the ship went down, the 900-odd soldiers on board were led and comforted by four chaplains: two protestant ministers, a rabbi and a Catholic priest. They were Reverend George L. Fox of Vermont, Reverend Clark V. Poling of Ohio, Rabbi Alexander Goode of Indiana, and Father John P. Washington of New Jersey.

The four ministers, all first lieutenants who had met at chaplain’s school at Harvard University, went from man to man, quelling the paralyzing fright that increased as the freezing water rose rapidly. “The sound of men in panic,” wrote one survivor, “is worse than any woman’s screams, hearing some calling for their mothers. It was awful.” The chaplains passed out lifejackets and guided men from below toward the open air and some hope of survival. All four gave their lifejackets to soldiers who had none. Rabbi Goode even gave away his gloves to a soldier who ultimately survived the bitter night and freezing water. “Without the chaplain’s gloves,” he said, “I would never have made it.” Of the 904 men who went into the frigid 34-degree water that night, only 229 survived.

As Dorchester slid bow first beneath the Atlantic, survivors saw something none of them would ever forget. The chaplains, who had done so much for so many, stood hand in hand—Catholic, Dutch Reformed, Jewish, and Methodist. As one survivor told the tale, the chaplains prayed for the safety of the men who were leaving the stricken ship on all sides of them. “It was the finest thing,” said another, “I have ever seen this side of heaven.” The four chaplains were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and Congress, in an act never repeated, created for the four the Medal for Heroism, the equivalent of the Medal of Honor.

Chaplain Albert Hoffman’s Lost Leg

The bitter Italian campaign, fought during the worst winter in memory, also took a terrible toll of chaplains. At least one, exhausted, simply died of a heart attack. The chaplains shared whatever miseries the troops endured. As one wrote: “Our clothes never dried, our shoes were soggy, our beds were laid in the mud for we had no cots, the food was miserable. We had lived on C-ration hash ever since we had come to Italy, and now it became C-ration hash soup.”

They buried young soldiers by the hundreds, collecting body parts and fingerprinting remains too badly damaged to be identified. Often the chaplains had to soak frozen dead fingers in hot water to obtain a usable print. It was a task to test the faith of any man.

In Italy, Chaplain Albert Hoffman was famous for retrieving wounded men from both sides stranded between the lines. In November 1943, he went alone into a minefield to help a wounded German, slogging through the muddy ground until a mine knocked him down. Uninjured except for a gash on his eyebrow, Hoffman got up and went deeper into the minefield. The next mine blew up directly beneath him, tearing off his leg. Medical personnel shouted that they were coming to get him. “I’m all right,” yelled Hoffman, “watch out for yourselves. There must be mines all around us.”

A third mine killed one doctor and wounded another. When more medics tried to reach Hoffman, he waved them away: “Stay back! You want to be killed? Get the mine sweepers in here!” Hoffman lay in the muck of the minefield for four hours before help reached him. Hoffman, who called himself an “infantryman’s chaplain,” became the most decorated chaplain of the war, receiving the DSC, the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, and the Italian Medal of Valor. His lost leg did nothing to diminish his passion for helping soldiers. Once he recovered, Hoffman spent all his time in military hospitals working with amputees, showing them that the loss of a limb was not the end of their lives.

The Chaplains of D-Day

The Normandy invasion had its own set of heroes. On Omaha Beach, Chaplain Joe Lacy walked through a rain of German fire to administer last rites and help the injured in any way he could. Short and rotund, Lacy’s calm and quiet courage inspired respect, particularly when he stood upright in the midst of the German fire, ordering stretcher parties through the fire to pick up badly hurt men. Lacy miraculously finished the day unhurt. He would receive the Distinguished Service Cross for his courageous day’s work.

The airborne chaplains in both armies were a breed apart, as were the paratroopers to whom they ministered. Captain Raymond Hall, an Episcopal priest, knew the bond that goes with a paratrooper’s little silver wings: “The men can talk to me now,” he said. One chaplain parachuted into a Fort Benning drop zone under a “streamer,” a chute that cleared the pack tray but did not fully open. “Who else,” wrote a soldier, “but a chaplain could fall a thousand feet with an unopened chute and live?”

Another D-Day DSC went to Chaplain Francis Sampson. As the fighting swayed back and forth behind the landing beaches and his unit fell back, Sampson volunteered to stay behind in a farmhouse with men too badly hurt to be moved. All through one night and the following day, he divided his time between caring for the wounded men and running outside to wave a white flag at advancing German troops. At one point, Sampson was seized by two German soldiers, who prepared to shoot him. Praying hard, the chaplain heard a shot, but it was not directed at him. It came from the pistol of a German officer who fired into the air and personally took charge of Sampson, showing the chaplain the Catholic medal he carried inside his uniform and photos of his baby.

“A Thousand Shall Fall Beside Thee”

If kindly angels watched over Sampson, other men were grateful for the protection of the Bible itself. One officer wrote home: “As I reached for my carbine, a shot struck me in the breast and blasted me down. Thinking I was dead, my pal was amazed when I rolled over and tried to get up. I pulled that little Bible out of my pocket and looked at the ugly hole in its cover.” The bullet had, he wrote, penetrated all the way from Genesis to the 91st Psalm, which reads in part, “A thousand shall fall beside thee, and ten thousand at thy right hand, but it shall not come nigh thee.”

Chaplain John Maloney, untutored in medicine, nevertheless managed to get plasma into a dying officer’s arm to save the youngster’s life. Maloney, like other airborne padres, jumped only with the tools of his trade: his Mass kit, containing the elements of Communion. The soldiers called it the “bread from Heaven.”

Wherever the fighting units were, chaplains went also. Mormon chaplain Eugene Campbell, searching for his unit, drove toward Fulda, in central Germany, passing through villages showing white flags. Later, when he explained where he had been, an officer told him, “Congratulations, chaplain, you just conquered two towns.”

“A Grand Rush to the Sacraments”

On the other side of the world, 58 chaplains went in with the Marine divisions invading Iwo Jima, or worked offshore with the invasion fleet. The troops faced the bloodiest battle of the Pacific War, and there was, as one chaplain put it, “a grand rush to the Sacraments” before the assault waves went in. One young officer promised to hoist an American flag on the peak of Mount Suribachi. Chaplain Charles Suver answered, “You get it up there and I’ll say Mass under it.” Suver’s days on the beach were, in his words, “a jumble of misery and torture and suffering.” He did not exaggerate. On Iwo Jima, the attacking Marines suffered nearly 30 percent casualties. Suver spent three days in a makeshift dressing station, comforting the wounded and the dying.

Although Suver slept the sleep of sheer exhaustion on his first night ashore, Chaplain James Deasy did not. He spent most of the night crawling through Japanese shell fire from foxhole to foxhole, encouraging the men, praying over the hurt, the dying, and the dead. For five nights, Deasy kept on with almost no sleep. On the third night, he was totally buried by a Japanese shell. When Marines came to his aid, his muffled shouts ordered them to stay under cover until the Japanese shelling stopped. Only then was the chaplain pulled from his grave, shaken but still alive.

Suver made good on his promise. On the fifth day of the fighting, as the national colors broke out on Suribachi and the Marines cheered, Suver and his assistant reached the top and promptly celebrated Mass while other Marines were still clearing nearby caves of diehard defenders. A board propped across two empty fuel drums was Suver’s altar, and his vestments were khaki. Not long afterward, Presbyterian chaplain Alvo Martin magically produced a little “field organ” and managed an Easter service, complete with a volunteer choir.

“He Believes in God and the Enlisted Man”

The fall of Iwo Jima marked the beginning of the end of the war, but the long road to victory still led through Okinawa and some 100,000 bitter-end defenders. At sea off Iwo Jima, kamikaze pilots hurled their aircraft in suicide dives at American ships, and one of their targets was carrier USS Franklin. On Franklin was Father Joseph Timothy O’Callahan. “He only believes in two things,” said one man. “He believes in God and the enlisted man.”

On Sunday, March 19, 1945, a Japanese plane slammed into Franklin. Raging fires following a massive explosion would kill almost 1,000 of the carrier’s crew. Father O’Callahan, pronounced a general absolution for the ship’s crew—his second of the day—and raced to help. With Methodist chaplain Grimes Gatlin, he went first to the airmen’s quarters, comforting, helping, and praying with the dying men. After Franklin took a second hit, O’Callahan ran to a congested ladder jammed with men frantically trying to climb out of the fiery hell down below. “Here, boys,” called the priest, “single file.” The sound of his voice restored order, and everyone in that part of the ship managed to climb to safety.

Above deck, O’Callahan faced a maelstrom of flame and explosion. Burned and mangled bodies were everywhere. O’Callahan took charge, organizing work parties to cool down or dump overboard munitions heated by the fires. Damage control parties pushed deeper into the ship, fighting the flames that raged through her, and the chaplain was with them.

Their heroics saved the carrier, and nobody contributed more than O’Callahan. Only later would the full extent of his courage be revealed: he was badly claustrophobic. Even so, he pushed into a dark gun turret to help jettison live rounds: “I did not so much mind the thought of being blown up,” he wrote later, “but did very much mind being hemmed in.” O’Callahan shunned publicity, modestly brushing off praise. “Any priest in like circumstances should do and would do what I did,” he said afterward, but Franklin’s captain of knew better. On the captain’s recommendation, O’Callahan was awarded the Medal of Honor for his astonishing heroics aboard Franklin.

By the time Okinawa was secure, more than 9,000 sailors were casualties, about a third of them dead. Many of the wounds, especially the burns, were hideous, and broken-hearted chaplains did all they could to help maimed and mangled men in terrible pain. Chaplain Fidelis Wieland died on board the hospital ship Comfort when she was deliberately bombed by the Japanese. He was one of three chaplains killed during the Okinawa campaign.

Chaplains in the China Burma India Theater

During the agony and heroism of the American island-hopping campaign across the Pacific, British and Indian troops were fighting a land war against the Japanese along the eastern borders of India and deep into Burma. In some of the worst terrain in the world, riddled with disease, crawling with mosquitoes, leeches, and an assortment of other voracious insect life, chaplains lived and suffered with the men. One such chaplain, Reverend N.S. Metcalfe, wrote of a terrible night march and a halt at aptly named Malarial Hill near Imphal. “Although I had started the foot trek with my field Communion set and 100 army prayer books,” wrote Metcalfe, “the set was lost in the blackness of the night, when I stumbled and dropped it over a cliff. However, with an orange box as an altar, army biscuits were used as wafers and some local whisky from the Naga headhunters used in lieu of wine. Despite the fact that it was watered down, it took the silver lining off a silver sports cup which had been pressed into service as a chalice.” It was all in a day’s work for Metcalfe.

One story speaks for all the chaplains who suffered for their flocks during the long years of World War II. Leonard Wilson was Bishop of Singapore when the Japanese invaded Malaya. Appointed a chaplain in the last days of the fighting, he was interned for 15 months in prison camps. Tortured by his captors, who wanted a confession of “anti-Japanese activities,” Wilson went on ministering. Prisoners could hear his voice as he gave Communion to a woman prisoner through the bars of his cell: “One, two, three, four, lift up your hearts!” When the torturers taunted him, asking him why God did not save him, Wilson replied: “God does save me. He does not save me by freeing me from pain and punishment, but he saves me by giving me the spirit to bear it.” And bear it Wilson did, even baptizing a Chinese fellow prisoner with the only available water from a lavatory basin.

The courage and compassion that British and American chaplains demonstrated throughout the war left their mark in the hearts and minds of the men they ministered to—and even upon some of the enemy. When Bishop Wilson returned to Singapore after the war, he held Mass and baptized and confirmed a number of people. Among them was one of the men who had tortured him.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments