By John Walker

Sent into north-central Virginia to threaten Richmond on a second front, McDowell had managed to get lost in the woods near Gainesville and lost touch with his command for 12 full hours. When he and his staff rode into Manassas Junction at dawn, he discovered that one of his three divisions—that of ailing Brig. Gen. Rufus King—had retreated during the night after a bloody two-hour clash with Confederate forces near Groveton. Another division, under Brig. Gen. James Ricketts, was four miles away at Bristoe Station, having withdrawn during the night from Gainesville.

In McDowell’s absence, Maj. Gen. John Pope, overall commander of the Army of Virginia, had issued orders to each of McDowell’s divisions for that day’s planned operations, a massive strike against the outnumbered Confederate corps of Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, dug in north of the strategic east-west Warrenton Turnpike near Groveton. Believing that he had Jackson boxed in, Pope planned an all-out attack on the troublesome and eccentric Rebel general. “The game is now in our own hands,” Pope gleefully told his staff, “and I do not see how it is possible for Jackson to escape without very heavy loss, if at all.”

To his dismay, Pope soon discovered that several of his units were not where he expected them to be. King and Ricketts had withdrawn from the Groveton-Gainesville area during the night. Convinced that he had to hold Gainesville for the morning’s attack to succeed, Pope ordered Maj. Gen. Fitz-John Porter to march his V Corps and King’s division to Gainesville (a much-chagrined McDowell would go along as well). Pope gave Porter and McDowell vague orders concerning what they were to do when they reached their objective. Although he did not issue specific orders for them to attack Jackson’s exposed right flank, Pope fully expected them to do so once they reached the field. In a welter of confusion and misapprehension, the Union Army was about to commence the Second Battle of Manassas.

First Clash at the Second Battle of Manassas

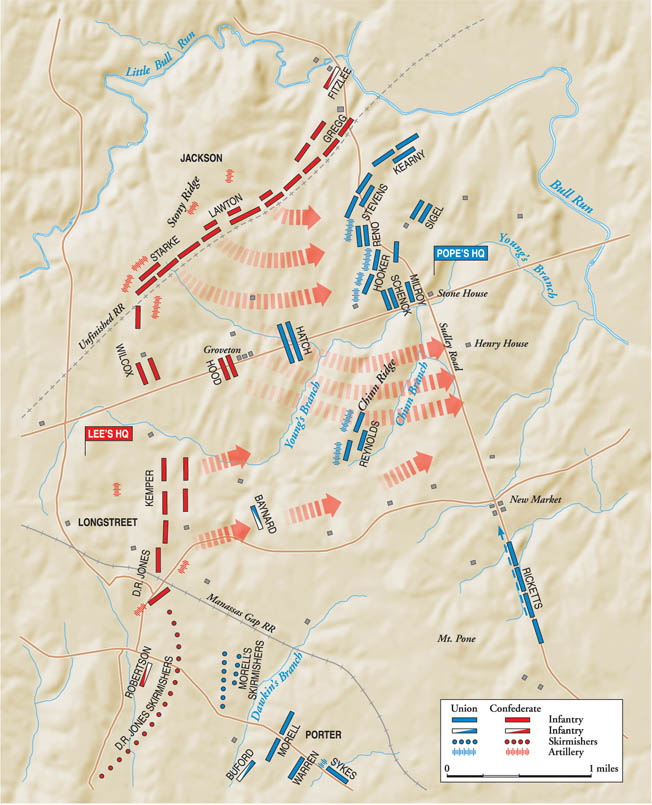

As the sun rose, Jackson’s troops, spread out for almost two miles, could see Union infantry and artillery massed on Henry Hill and Chinn Ridge. With Maj. Gen. James Longstreet still hurrying through Thoroughfare Gap to join him, Jackson moved his three divisions a short distance northeast behind an embankment of the unfinished Manassas Gap Railroad, a ready-made system of defensive works running from Sudley Springs down to the Warrenton Pike. Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s 4,000 men took up positions on the critical left flank, 200 yards behind the embankment. On Hill’s far left, Brig. Gen. Maxey Gregg’s brigade of South Carolina regiments dug in on a ridge overlooking Sudley Road, 60 yards behind the unfinished railroad. Anchoring the Confederate center was the division of Brig. Gen. Alexander Lawton; two brigades were posted along the embankment and the remaining two, under Brig. Gen. Jubal Early, were held in reserve. On Jackson’s right, Brig. Gen. William Starke threw out skirmishers on the embankment; the remainder of his division waited in three lines 200 yards behind the skirmishers on a wooded ridge.

Major General Franz Sigel, the senior Union officer on the field, was unaware of Jackson’s exact location or strength, but he sent his troops forward along a two-mile front, feeling for the enemy’s line. Brig. Gen. Carl Schurz’s two brigades were on the Union right, marching north astride the Manassas-Sudley Road. Brig. Gen. Robert Milroy’s Independent Brigade was on Schurz’s left; and Brig. Gen. Robert Schenck’s two brigades advanced astride the Warrenton Pike toward the enemy’s right. The division of Brig. Gen. John Reynolds moved up on Schenck’s left, south of the pike.

One of Schurz’s brigades quickly clashed with Rebel skirmishers in the woods on the extreme Confederate left. Hearing the firing, Gregg ordered Major Edward McCrady’s 1st South Carolina forward, and it collided with the 54th and 58th New York Regiments. Despite orders to avoid a general engagement, Gregg committed more troops, sending in the 12th South Carolina under Colonel Dixon Barnes. Schurz committed another regiment as well, and the woods in front of the rocky knoll began filling with smoke from the fire of 1,500 muskets.

General Robert Milroy’s Mistake

Milroy, Schenck, and Reynolds, meanwhile, dispatched their troops against Jackson’s center and right; Milroy moved north of the pike toward the Groveton Woods, driving back Rebel skirmishers there. As Schenck’s brigades advanced along the pike with Reynolds to their left and approached Groveton, they came under intense fire from eight Rebel batteries deployed in front of Starke’s division northeast of the Brawner home. After Schenck asked that he send a battery north of the pike to outflank and drive off the Rebel guns, Reynolds sent forward a Pennsylvania battery and the infantry brigade of Brig. Gen. George Meade. Reynolds’s four cannons moved north of the pike and up the slope near the Brawner home, unlimbering several hundred yards south of Shumaker’s line, and an intense artillery duel raged for the next hour.

Milroy, an impetuous Indiana lawyer who despised West Pointers, committed a serious tactical error after hearing heavy firing coming from Schurz’s front a half mile to his right. Although he actually knew little of Schurz’s situation, he decided to send two regiments 600 yards across the enemy front in support. His troops, rather than coming up abreast of Schurz’s line, advanced 400 yards across open ground into the front of Lawton’s division along the embankment, where they were raked unmercifully by massed sheets of musket fire. Milroy committed another regiment; when it was routed he sent in his fourth and last regiment, which got to within 50 yards of the embankment before it too withered under heavy fire and fell back.

Schurz sent his entire division forward; two regiments fought their way across the unfinished railroad into a cornfield opposite Gregg’s 14th South Carolina, but Confederate cannons and reinforcements drove the attackers back to the excavation. Two more Union regiments pushed through the woods and fought their way to the embankment across from Gregg’s right where it connected with the brigade of Brig. Gen. E.L. Thomas. Hill’s defenders held, and the fighting settled into a vicious stalemate.

The Full Army of Northern Virginia

Skirmishing and artillery fire continued through the morning while the other half of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia edged closer to the battlefield. Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Texas Brigade was in the lead. When the gray columns reached Gainesville, Lee turned the infantry units left onto the Warrenton Pike while Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry continued ahead to reconnoiter. At 10 am, Hood arrived and moved his brigade into positions facing east, its left astride the pike. Colonel Evander Law brought up his brigade on Hood’s left and connected with Jackson’s right, after which Brig. Gens. D.R. Jones, James Kemper, and Cadmus Wilcox moved their divisions into line and sent out large numbers of skirmishers. The weight of Hood’s arrival pushed back Reynolds. Lee’s line now stretched for almost four miles and resembled a pair of huge, gaping jaws ready to snap shut.

Having reached the battlefield ahead of his foot soldiers, Longstreet deployed his artillery along a low, clear ridge 200 yards northeast of the Brawner home, from which Confederate guns could bracket the Federal positions near Groveton as well as the open field in front of Starke’s division on Jackson’s right. Soon, 19 of Longstreet’s cannons were dueling with Union batteries near Groveton, less than a mile away. Lee wanted an immediate advance, but Longstreet balked. Unsure of the ground to his front or the exact positions of the enemy forces, he asked for more time to conduct a reconnaissance.

Porter and McDowell Advance Toward Gainsville

Meanwhile, Porter and McDowell had been marching 14,000 men up the Manassas-Gainesville road, with Brig. Gen. George Morell’s division leading the column and Brig. Gen. George Sykes’s division of regulars close behind. About two miles short of Gainesville, they spotted huge dust clouds to their front indicating a large enemy presence (Stuart, immediately noticing Porter’s advance, had ordered Captain Thomas Rosser to have his 5th Virginia horse soldiers drag brush and twigs along the ground as a ruse). At 11 am, the men of Morell’s lead brigade approached a ridge over Dawkins’ Branch and spotted mounted Confederates to their front. Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin sent half of the 62nd Pennsylvania ahead as skirmishers.

When the sounds of skirmishing to his front increased, Porter halted his column and conferred with McDowell, who had received a dispatch from Brig. Gen. John Buford that a huge Rebel column, Longstreet’s corps, had passed through Gainesville that morning. Just then new orders from Pope arrived, instructing Porter and McDowell to continue their march, halt if they connected with friendly troops, and be prepared to fall back to Bull Run that evening. With a Confederate force of unknown size to his front, Porter decided to sit tight. He pulled his divisions into defensive positions astride the road and remained there for the rest of the day.

With Porter’s corps stalled, McDowell countermarched King’s division (now commanded by Brig. Gen. John Hatch, King having been incapacitated by a fit of epilepsy) back to the Manassas-Sudley road to connect with Ricketts’s division moving up from Bristoe Station. Meanwhile, Pope arrived on the field at 1 pm and was pleased with what he found—skirmishing along a two-mile front and Jackson “brought to a stand.” Pope was convinced that his decision to send Porter and McDowell up the road to Gainesville would turn out to be a stroke of genius; when they arrived they would be in perfect position to launch a devastating strike against Jackson’s exposed right flank. The problem was that none of Pope’s orders said anything about an attack upon enemy forces; Pope simply assumed Porter and McDowell would attack Jackson’s right and based his plan of attack on that bit of particularly wishful thinking

Grover Repulsed

Pope ordered Maj. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman to “occupy” Jackson by testing the Rebel center; a frontal assault by Brig. Gen. Cuvier Grover’s brigade would be supported by Brig. Gen. John Robinson’s brigade. Grover’s three frontline regiments made it to within a few yards of the embankment before they were spotted by the Georgians of Thomas’s brigade, who rose and delivered a deadly massed volley. The blue line slowed only briefly before carrying the embankment in a bayonet assault.

Grover’s sudden thrust threatened to cut off Gregg’s brigade from the rest of Jackson’s line. Gregg withdrew Barnes’s 12th South Carolina from his far left and sent it to Thomas’s aid as the fighting escalated. The survivors of Grover’s first wave, trapped in a deadly pocket of fire along a 500-yard front, were suddenly overlapped on both flanks, and in minutes Grover’s attack sputtered and his survivors streamed to the rear, leaving behind 486 troops killed or wounded.

45 Minutes of Fighting

Pope was growing anxious—it was late afternoon and Porter and McDowell had not yet appeared. Another piecemeal, unsupported Union assault, this one against Jackson’s center by the 1,500-man brigade of Colonel James Nagle, met the same fate as Grover’s: very little accomplished at a cost of another 500 casualties. Pope, sending a preemptory order to Porter to attack at once, ordered another strike, this time by Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny against the Rebel left near Sudley Church. Shortly after 5 pm, Kearny sent 2,700 men forward with orders to wrap around Hill’s left and drive the defenders out of the excavation. Kearny personally led three regiments into battle over ground covered with dead and wounded. The 63rd Pennsylvania on Kearny’s left soon lost contact with its two sister regiments—the 105th Pennsylvania and 3rd Michigan—in the thick underbrush.

Meanwhile the 105th Pennsylvania and 3rd Michigan struck Gregg’s South Carolinians, who fled after suffering severe losses, exposing the flank of Gregg’s brigade, which was now under frontal assault by the 40th and 101st New York and the 4th Maine. After the exhausted 1st and 13th South Carolina also broke for the rear, the embattled Gregg appealed for help; it arrived in the shape of Brig. Gen. Lawrence Branch’s three North Carolina regiments, who crashed against Kearny’s right and slowed his advance. Gregg, brandishing his grandfather’s Revolutionary War sword, called out, “Let us die here, my men,” while groups of soldiers formed a strong line of resistance on a hill 200 yards behind the embankment.

Early hurried to the front, leading 2,500 reserve troops, and emerged from the woods to find the Confederate line barely holding along the lower slopes of Stony Ridge. Early’s nine regiments crashed into Kearny’s line and overwhelmed the exhausted attackers, who were low on ammunition and had suffered heavy losses in 45 minutes of intense fighting. Within 10 minutes of Early’s arrival, Kearny’s entire force was streaming back through the woods, pursued as far as the embankment, ending the fighting on Jackson’s front for the day.

Reconnaissance in Force

With less than two hours of daylight remaining, Lee again suggested a general advance. Longstreet demurred once more, suggesting a reconnaissance in force to prepare for an attack the following morning. Lee agreed, calling off a general advance set for the next morning and deciding instead to wait for an attack by Pope. Meanwhile, Pope sent an optimistic message to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck in Washington, estimating his losses at between 6,000 and 8,000 while grossly overestimating the Confederate casualties and claiming that the enemy was retreating toward the mountains. In fact, Lee’s two wings occupied virtually the same ground they had the previous day, and Longstreet had been bolstered by the arrival of Colonel Stephen D. Lee’s artillery battalion and the infantry division of Brig. Gen. R.H. Anderson.

Porter arrived early on August 30, adding 8,000 more troops to Pope’s force. Pope met with his commanders at his headquarters near the Warrenton Pike-Sudley Road intersection, and they convinced him to launch a renewed strike against the enemy left, where some success had been gained the previous day. Pope agreed but issued no direct orders; instead, the morning hours passed while Pope waffled, paralyzed by indecision, trying to reconcile his belief that the enemy was retreating with numerous reports to the contrary.

“Press the Enemy Vigorously”

At 11 am, McDowell and Heintzelman asked to be allowed to reconnoiter the Union right on their own. While they were gone, Pope made up his mind—the Rebels were retreating, a pursuit was in order, and Porter was to attack immediately. A bit later, when McDowell and Heintzelman returned from their half-hearted reconnaissance and reported that they had seen little evidence of a strong enemy presence, Pope was further convinced. At noon he issued revised orders for a two-pronged pursuit. Rather than attacking, Porter would instead lead the pursuit west along the Warrenton Pike, supported by Hatch and Reynolds. Ricketts’s division, backed by Heintzelman, would pursue Jackson along the road leading from Sudley west to Haymarket. The chase was to begin at once. Pope told his officers, “Press the enemy vigorously during the whole day.”

Porter prepared to launch the largest Union assault of the battle. He faced a formidable task. To Porter’s front were some of the best troops in Lee’s army—Jackson’s old division, now commanded by Starke—holding a strong position behind the unfinished railroad, arrayed in two lines of battle 200 yards apart. Porter’s men would have to cross almost 700 yards of open pastureland, the last 150 sharply uphill, to close with the enemy. At 3 pm, Porter’s 10,000 men poured out of the woods like an avalanche, the sudden appearance of the blue columns sending a shock wave through the Confederate ranks. Colonel Leroy Stafford’s Louisiana brigade, arranged in two lines, held Starke’s left; to Stafford’s right, the 42nd Virginia of Colonel Bradley Johnson’s brigade waited in the unfinished railroad at its deepest point—the “Deep Cut,” as it was known. On the right of the 42nd, where the railroad bed ran over flat ground, Johnson’s 48th Virginia waited in a grove of trees 80 yards in front of the excavation.

On the Union right, the 24th and 30th New York emerged from the timber and were immediately struck by a massed volley fired from the excavation by Stafford’s 1,000 Louisianans. The blue line recoiled but continued forward as clouds of white smoke began to obscure the field. When the New Yorkers reached Schoolhouse Branch, the Confederates rose and fired a second volley. Unbroken, the 24th and 30th closed on the excavation. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Daniel Butterfield’s units were pushing across the field. At Schoolhouse Branch, the men of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Roberts’s brigade felt the sting of enemy rifle fire from their front and artillery fire from their left. By now S.D. Lee had brought the full weight of his 18 guns to bear from the ridge 1,000 yards away. Roberts’s men paused for a few moments before continuing on, the din of battle rising to a deafening roar.

The smoke, dust, and noise combined to sow confusion in the Union ranks. The 1st Michigan made it to within 50 yards of the embankment before it was halted by enfilading fire and went to ground. The 13th New York and 18th Massachusetts advanced to within yards of the excavation, took cover behind bushes and rocks, and continued their fire. On Roberts’s left, the 17th New York emerged from the woods and moved forward alone. Without stopping at Schoolhouse Branch, the men of the 17th reached the base of the slope leading up to the unfinished railroad and rushed up the hill with a mad yell. When they reached the crest in front of Johnson’s brigade 50 yards from the excavation, a deadly blast of artillery and musket fire halted their line.

The exposed 48th Virginia promptly turned and headed for the rear. Along a quarter-mile front, the fighting raged unabated at extremely close ranges. Convinced that his two remaining regiments could not hold, Johnson ordered his two reserve units, the 1st Virginia Battalion and the 21st Virginia, to leave the woods and come up in support. The two fresh units moved into the open field and were promptly shredded by massed volleys of musket fire. Fewer than 300 men made it across the field, tumbling into the Deep Cut alongside the 42nd Virginia.

The retreat of the 48th Virginia opened a dangerous gap between Johnson’s right and Brig. Gen. William Taliaferro’s left. Jackson, after ordering Hill to reinforce the battered Rebel right, sent a request to Lee and Longstreet, asking for reinforcements. Longstreet concluded that sending a division of infantry would take too much time; the attack, he said, must be broken by artillery instead. Longstreet ordered Captain Will Chapman’s Dixie Battery to move to a low knoll just north of the pike. Chapman’s four guns added their fire to that of S.D. Lee. The Confederate cannons pinned the attacking Union columns against the railroad, making retreat nearly impossible.

The General Advance

Back at Groveton Woods, Porter concluded that sending additional troops across 700 yards of ground dominated by Rebel cannons would lead to disaster and decided to withhold Sykes’s entire reserve division. Porter decided against committing his reserve brigades on the right, essentially abandoning the other Union troops to their fates. Almost an hour of sustained combat had pushed the Confederate defenders to their limits; some were leaving the line to scavenge among the dead and wounded for ammunition while others had resorted to throwing rocks at their enemies. By that time, however, the Federal onslaught was almost spent. When a fresh brigade from Hill’s division came up in support, the crisis ended for the southerners. All along the line Union officers passed the order to retreat.

Moments after Porter’s attack dissolved, Longstreet and Lee simultaneously ordered a general advance of the Confederate right wing. With no more than three hours of daylight remaining, one of the largest counterattacks of the entire war got under way. Longstreet’s objective, Henry Hill, was almost a mile and a half away and shielded the Union route of retreat along the Warrenton Pike. About 500 yards west of Henry Hill lay Chinn Ridge, the only terrain feature blocking Longstreet’s legions. Another 500 yards farther west, directly in the path of the oncoming gray tide, waited Colonel Gouverneur Warren’s brigade of two Zouave regiments. Just after 4 pm, the 5th Texas moved out of the woods and started forward. On their left was Hampton’s Legion, many of its men veterans of the fighting 13 months earlier, along with the 18th Georgia and 4th Texas. Four fresh Confederate regiments entered the open fields into the path of the 10th New York’s skirmishers, who managed to get off one massed volley before they were overwhelmed and fell back in panic.

The Zouaves could not see their enemy through the clouds of smoke. By the time the fleeing skirmishers of the 10th finally cleared the 5th New York’s front, the men of Hood’s brigade were already at the edge of the woods just 40 yards away. The 5th Texas outflanked the left of the 5th New York, while Hampton’s Legion and the 18th Georgia crashed against their center and right. The colorfully dressed Zouaves made easy targets in the open field. In the first three or four minutes, the 5th suffered at least 100 casualties. Warren yelled out an order to retreat but could not be heard above the din; without orders to fall back, many Zouaves stubbornly held their ground. After another few minutes it became clear that to remain where they were was folly, and every man who could run broke to the rear, closely pursued by screaming Confederates.

As the Zouaves hurried down the slope leading to Young’s Branch, Hood’s troops moved to the crest of the ridge and slaughtered them as they attempted to follow Warren across the stream. In the first 10 minutes on the ridge, some 300 men of the 5th New York had been killed or wounded; at least 120 were killed outright—one of the heaviest regimental losses of the entire war.

After pausing at Young’s Branch, Hood’s four regiments splashed across the stream and headed up the slope. Hood’s brigade advanced almost a mile, but its rapid pace put the men far ahead of the rest of the Southern forces. Knowing that his men needed cover, Hood ordered his regiments to the right toward a patch of woods. Convinced that his tired troops were not in sufficient numbers to capture Chinn Ridge, Hood decided to wait for reinforcements.

Charge of the South Carolinians

In short order, the 18th South Carolina charged out of the woods toward the Union left, only to be hit in the flank by artillery fire and in front by the fire of the 73rd and 25th Ohio. Next came the 17th South Carolina, commanded by that state’s former governor, Colonel John Means, who soon fell mortally wounded. The Union regiments crumbled and fell back beyond the crest of the ridge. Three brigades of Kemper’s division arrived in the fields south of the Chinn house as the fighting raged on. Kemper’s front line consisted of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins and Colonel Eppa Hunton, with Colonel Montgomery Corse’s brigade 250 yards behind.

Thousands of Confederates in several lines of battle advanced up the ridge and closed on the Union line from three directions. When Hunton and Jenkins advanced toward the crest of the slope against the Union center and left, the blue-clad forces unleashed a devastating volley that staggered parts of Jenkins’s line. Within minutes, however, the Confederates reorganized and came on once more, to within 40 yards of the Federals. The battle continued along a 400-yard front, the outnumbered Union brigades suffering horrendous losses.

As the Union line was pushed slowly back along the crest of the ridge, Confederate horse-drawn artillery reached Bald Hill southeast of Chinn Ridge and began firing into the Union left. This new flanking fire was more than the Federals remaining on the slope could bear; the blue line atop the ridge wavered and then broke altogether. Belated reinforcements arrived as the blue lines collapsed and watched as waves of Confederates advanced in deep, dense masses. Minutes later the remaining Union troops on Chinn Ridge, facing insurmountable odds, withdrew, leaving Chinn Ridge in Confederate hands.

The Defense of Henry Hill

Fortunately for Pope, the stubborn defense of Chinn Ridge gave him time to arrange his remaining troops into formidable defensive positions on nearby Henry Hill. At 5:30 pm, Pope ordered the right wing of his army to pull back on line with his left on Henry Hill. By 6 pm, he had four brigades on Henry Hill along a half-mile front extending from north of the Henry house ruins into and beyond the woods on the southern edge of the plateau. Three batteries on the crest of the hill would fire in support of the Union line; more troops were on the way.

Longstreet and Lee had been working to gather additional units for the drive on Henry Hill. The first to respond was Brig. Gen. R.H. Anderson, whose division left the Brawner farm at 4:50 pm, its three brigades crossing to the south of the pike for the two-mile march east. Longstreet ordered Wilcox to advance his division as well; unfortunately, Wilcox misunderstood the order and sent only one of his three brigades south of the pike and on toward Henry Hill. While these units began their march to Henry Hill, D.R. Jones renewed the Confederate advance, sending both of his brigades to capture the vital Warrenton Pike-Sudley Road intersection. His men got to within 200 yards of their objective before Union troops on Henry Hill spotted the movement.

Reynolds immediately ordered Meade’s brigade to attack the Confederate column, and with artillery firing over their heads, Meade’s men moved down the slope. The sudden appearance of Meade’s brigade on the Georgians’ right crushed Jones’s hopes of cutting off the enemy units on Dogan Ridge. Brig. Gen. Henry Benning wheeled his men to the right to face Reynolds’s line, pointed to the artillery on the hill above it, and ordered his regiment to charge. Anderson’s brigade wheeled to the right as well and moved up on Benning’s right. Minutes later nearly 3,000 Georgians were moving up the western slope of Henry Hill along a half-mile front, the largest single movement of Longstreet’s attack.

Benning’s regiments emerged from the Chinn Branch valley into the face of the combined fire of Meade, Seymour, Milroy, and the Union batteries. The gray line recoiled but recovered and continued up the slope, getting to within 80 yards of the enemy. On the Confederate right, Anderson’s troops moved through heavy timber toward the crest. As they came out of the woods, Anderson’s men recoiled from an initial volley but kept coming as well, getting to within 50 yards of Sudley Road before taking cover and continuing the fight.

The Union Line Unravels

Every frontline Union brigade was now heavily engaged. Despite the Union artillery and the formidable positions held by the defenders, the fire of the Georgians was putting tremendous pressure on the Federal line. Jones’s brigades were delivering such a fire that the Union line, and not the Confederate, was wavering; Reynolds’s two left-flank regiments gave ground, along with the bulk of Milroy’s men, who abandoned Sudley Road altogether. The 15th Georgia seized the opportunity and lunged forward into the breach, gaining a foothold on the road just yards from the Yankee batteries. The situation on the Union far left deteriorated as well when a Confederate battery arrived, its four cannons opening fire from near the Conrad home directly on the Union left, raking the thin blue line.

The entire Union defense on Henry Hill was in crisis. After Milroy and Meade appealed for help, Lt. Col. Robert Buchanan’s brigade came up at the most opportune moment. After getting his first three regiments deployed, Buchanan rode back and got his remaining two, the 3rd and 5th U.S., and placed them in the center of the Union line. The appearance of fresh troops after 45 minutes of heavy fighting was more than Benning’s four tired regiments could bear. The 17th Georgia, on Benning’s right, gave way, exposing the right of the 15th Georgia, and although they tried mightily to hold onto their salient on the road, the men of the 15th finally fell back down the hill to Chinn Branch. The situation on Benning’s left deteriorated as well; the 20th Georgia, suffering in the open under a rain of shells fired from Henry Hill 300 yards away, was ordered to pull back. At that point, although the fighting continued sporadically for another 30 minutes in the growing darkness, the Confederate attempt to overrun Henry Hill essentially came to an end.

McClellan Replaces Pope

By 7 pm, the retreat on the Union right to the heights east of Sudley Road was complete, the blue army presenting a solid front even though division and corps cohesiveness had eroded significantly. By 11 pm, most of Pope’s army had crossed Bull Run at the stone bridge or at Farm’s Ford a half mile to the north, their ebbing spirits further dampened by a driving rainstorm. More than 3,000 dead and 15,000 wounded littered the field. Jackson had suffered almost 4,000 casualties, while Longstreet had lost more than 4,700 men killed, wounded, or missing in less than four hours—some 15 percent of the Confederate forces engaged. Pope’s army, defeated but essentially intact, had suffered 13,824 casualties—1,716 killed, 8,215 wounded, and 3,893 missing.

With the Union facing its gravest threat since the commencement of hostilities, President Abraham Lincoln on September 2 reinstated Maj. Gen. George McClellan to command of all the Federal forces in and around Washington; Pope was banished to Minnesota to command Union troops fighting a Sioux uprising there, his 74 days in command of the Army of Virginia making for one of the sorriest chapters in the history of the United States Army. Conversely, the fortunes of the Confederacy had never looked brighter. Less than six months earlier, Southern armies had been on the defensive everywhere: New Orleans lost, Corinth and Richmond threatened, Missouri gone, and the entire Mississippi Valley seemingly about to follow. Now the South had regained the initiative and was on the offensive in every major theater of the war. The Confederacy had reached its true high-water mark at Manassas. Never again would it be as close to victory.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments