By Al Hemingway

On the humid morning of August 19, 1942, infantrymen from Company A, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines carefully eyed the landscape for any signs of Japanese soldiers as they slowly made their way through the thick jungle on the island of Guadalcanal, located in the Solomon Islands. Led by Captain Charles H. Brush, they had orders to follow the coastal road to the Koli Point-Tetere area.

Father Arthur Duhamel, a Catholic priest from Massachusetts who resided on Guadalcanal, had informed an earlier patrol that a large enemy force was nearby. Coast watchers also verified that the Japanese had established a radio station near Taivu and that they had the Marines under constant surveillance. Several days later, Brush’s 60-man group was dispatched to destroy the communications building and equipment.

At noon, the leathernecks stopped to eat and take a break from the intense tropical heat. As several Marines neared a clump of fruit trees, they saw a Japanese patrol casually strolling by and “not in military formation.”

Brush sent the majority of his men in a frontal assault while one platoon scurried around the enemy’s right to outflank them. In less than an hour, 31 enemy soldiers lay dead. The Marines had lost three killed and three wounded.

Searching the bodies, the Marines discovered quite a few documents that looked official. Brush commented years later: “With a complete lack of knowledge of Japanese on my part, the maps the Japanese had of our positions were so clear as to startle me. They showed our weak spots all too clearly.”

The young captain also noted that this group had possessed “an inordinate amount of rank” and their uniforms were in pristine condition. This could mean only one thing: they had just arrived on Guadalcanal as an advance party for a much larger force preparing to attack the Marine perimeter at Henderson Field. Knowing he had unearthed some vital information, Brush sent his runner back to headquarters to give the papers to the G-2 Section (Intelligence) to study.

Ninety miles long and 25 miles at its widest point, Guadalcanal was of strategic importance to U.S. strategy in the early days of World War II. Since landing on August 7, the Marines had spent a considerable amount of time expanding the airstrip. Named Henderson Field to honor Major Lofton Henderson, a Marine pilot killed at the Battle of Midway, the airstrip would prove invaluable in the months to come.

Ironically, the main island was quickly seized because few enemy soldiers were stationed there. The first week saw the majority of ground combat on the neighboring islands of Gavutu and Tanambogo where the Raiders, paratroopers, and elements of the 2nd Marines fought a tenacious foe. Some Japanese soldiers spoke perfect English as they attempted to taunt the leathernecks with: “Die, you dirty bastard Marines, die!” In the end, however, the enemy would die in fanatical suicide charges, a trademark of the Japanese for most of the war.

But then things started to disintegrate as the Japanese delivered a stunning blow to the American, British, and Australian navies on the night of August 9, 1942. The enemy, more adept at night fighting, sank or severely damaged a number of cruisers and destroyers during the Battle of Savo Island. With the sinking of these ships, the Marines onshore dubbed Sealark Channel “Iron Bottom Sound.”

Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner also informed Maj. Gen. Alexander A. “Sunny Jim” Vandegrift, commanding the 1st Marine Division, that he had to weigh anchor and withdraw. This departure of the fleet left the Marines virtually stranded. Turner’s transports had unloaded only half of the much-needed supplies for Vandegrift’s leathernecks. Also, with no naval gunfire support, the Marines were vulnerable to Japanese air, land, and sea assaults. The enemy could now travel unimpeded to deliver supplies and reinforcements from Rabaul down the Slot, a channel running from Bougainville in the Northern Solomons to Guadalcanal in the south.

On August 15, a few transports did manage to slip the enemy gauntlet and drop off additional food, ammunition, bombs, and aviation gasoline to the leathernecks. Although life on Guadalcanal was miserable, the Marines could get some comfort knowing that their presence had upset the timetable for the Japanese takeover of New Guinea. Enemy planners expected a quick victory against the Marines since they firmly believed that they were “haughty, effeminate, and cowardly” and also had “no stomach for fighting in rain or mist or in the dark.”

Lieutenant General Haruyoshi Hyatutake, commanding general of the 17th Army at Rabaul on the island of New Britain, had the unenviable task of ousting the American invaders from Guadalcanal so Japan could continue its conquest of the Pacific. Resembling a college professor rather than a senior military officer, Hyatutake assembled 6,000 troops to retake the airfield. Unfortunately, he had grossly underestimated two things—the size of the American force and the tenacity and will of the Marines to hold on to Guadalcanal.

The Marines also had another asset at their disposal—a top secret code-breaking group that worked in Washington, D.C., Hawaii, and Australia. The job of these codebreakers was to intercept, decode, and analyze the data on the enemy. This was an enormous task because of the difficulty of the Japanese language. In spite of this, cryptanalysts deciphered the message about the impending invasion and delivered it through channels until it reached Vandegrift just prior to the Japanese landing.

“Sunny Jim” had to Make a Decision… Attack or Wait for the Enemy to Come to Them.

When Brush’s runner arrived at headquarters, the information was handed over to the division intelligence officer, Captain Sherwood “Pappy” Moran, who had lived in Japan prior to the war and spoke the language. Examining the documents in his “fetid, blacked-out intelligence shack,” Moran concluded that they were indeed part of a larger force that had departed Truk and had recently disembarked on Guadalcanal.

Despite this knowledge, Vandegrift was still in a quandary. The papers did not reveal the size or plans of the Japanese troops. “Sunny Jim” had to make a decision: attack or wait for the enemy to come to them. He chose to defend the perimeter and not pursue offensive operations. The enemy could stage a two-pronged maneuver, and the leathernecks already had enough ground to defend without weakening it further by sending troops out to pursue the Japanese. Also, Vandegrift’s men were low on fuel and ammunition and this in itself “precluded expenditure of the amounts required for an all-out attack.”

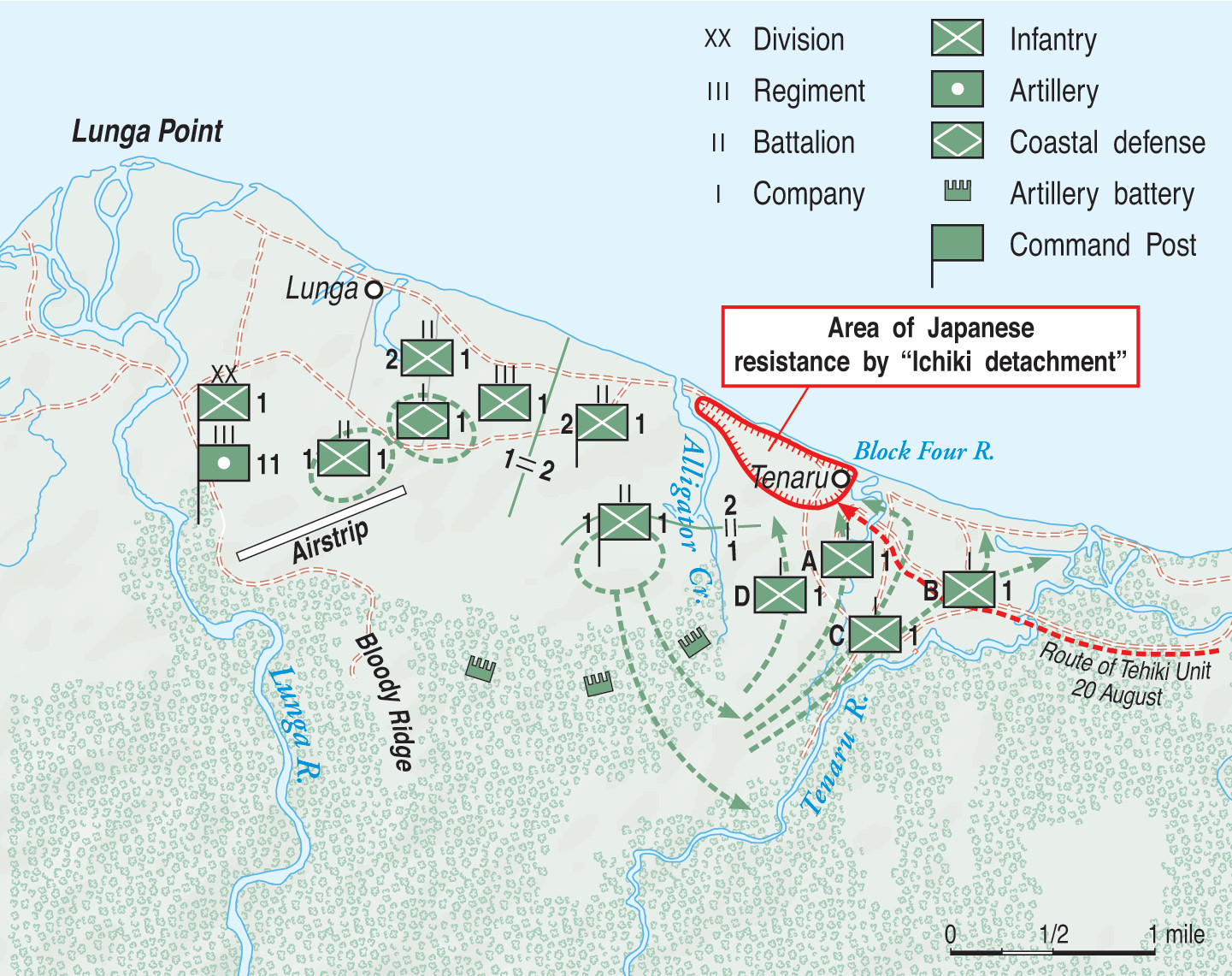

Orders were issued to Colonel Clifton B. Cates, commanding officer of the 1st Marines and a veteran of trench warfare in World War I, to lengthen his lines. Cates turned to Lt. Col. Edwin A. Pollock, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, to prepare his men for the seemingly inevitable attack. A veteran of the Banana Wars in Central America, Pollock was a no-nonsense Marine. His battalion stretched for 2,700 yards. A thousand yards of this was along the Lunga coast and the remainder covered the Ilu (Tenaru) River’s western bank.

The poor quality of the maps possessed by the Marines during the initial invasion led to several of the rivers being identified incorrectly. Pollock’s positions were actually on the Ilu River, dubbed Alligator Creek by the local residents (although crocodiles, not alligators, inhabited the river), not the Tenaru. The Marines thought this was the Tenaru River, which was actually located farther to the east. Alligator Creek was in reality a tidal lagoon, separated from Sealark Channel by a sandbar. This spit ranged in size from 25 to 50 feet wide and about 100 feet long and protruded approximately 10 feet above the water. It was particularly vulnerable to an enemy assault.

It was here that Pollock placed several platoons from Battery B, 1st Special Weapons Battalion strengthened by two rifle platoons from Company H. Machine guns of .30- and .50-caliber and 37mm antitank guns dotted the area protected by sandbags and logs found nearby. Not equipped with gloves, the riflemen nevertheless strung razor-sharp barbed wire to further impede the attackers’ progress. This area would be known as Hell’s Point by the Marines when the fighting was over. And it would be a name well earned.

In addition to fortifying the spit, one platoon from Captain Martin Rockwell’s Company E and Captain John Howland’s Company F dug in along the center of the perimeter. The other two platoons from Company E and the remainder of Company H, under Captain James Ferguson, augmented by heavy weapons, covered the river approaches. Captain James Sherwood and his Company G (minus 1st Platoon) were in battalion reserve. Immediately behind the riflemen were the mortar sections standing by to deliver much-needed support during the attack.

While Vandegrift was deploying his forces and preparing his lines, the Japanese were busy as well. General Hyatutake selected the 28th Infantry Regiment, 7th Division to spearhead the assault to retake Guadalcanal. Led by Colonel Kiyono Ichiki, it had been one of the units slated to assault Midway Island prior to the crushing naval defeat suffered by the Japanese in June 1942. After the Japanese Navy’s loss at Midway, however, Ichiki’s men steamed toward Japan to reorganize and get some rest.

With the rapidly changing developments on Guadalcanal, those orders were changed, and they went to Truk. Boarding a half-dozen destroyers, the reinforced battalion, an estimated 800 men, disembarked unnoticed on Guadalcanal near Taivu on August 18. Ichiki’s luck ran out when the reconnaissance patrol he had sent out was ambushed by Brush’s platoon the following day, alerting the Marines to their presence on the island.

When the exhausted survivors from the ill-fated patrol returned to relay the horrifying news that most of their comrades been killed, Ichiki wasted no time in ordering a company to come to their aid. By the time they arrived on the scene, it was too late. Ichiki left behind a burial detail and continued his march westward toward the Marine perimeter. Just before dawn on August 20, the battalion arrived at the small hamlet of Rengo, where Ichiki decided to camp.

That afternoon, Ichiki met with his officers to plan the attack on the leathernecks. After nightfall, the battalion would advance in a westerly direction and seize the area once occupied by the 11th Construction Unit between Alligator Creek and Lunga Point. When this was accomplished, the unit would break up into two formations. One section would capture Henderson Field, and the other would take a Marine strongpoint at Lunga. Even though he knew the Marines knew he was on Guadalcanal, Ichiki had the utmost confidence in his men. His ranks were filled with seasoned troopers who had seen combat in Manchuria and China. They were outstanding night fighters and well disciplined, like most Japanese soldiers, and they considered themselves unbeatable.

Ichiki gave strict orders not to make any noise as they approached the Marine positions. He did not anticipate any serious challenge from the defenders. Like the majority of Japanese soldiers, Ichiki had a low opinion of the American soldier’s fighting ability. Experts at night combat, he and his men fully expected to wipe out the enemy with “one brush of the armored sleeve.”

As the overconfident Colonel Ichiki was issuing last-minute orders to his men, the Marines received a welcome surprise. Nineteen Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighter planes from VMF-223 landed at Henderson Field late in the afternoon. Accompanying them were a dozen Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bombers. These aircraft provided a boost in morale for the weary “ground pounders” of the 1st Marine Division. Little did they know that in a matter of hours they would be involved in the upcoming struggle along the Tenaru (Ilu).

As the Enemy Rifleman Peered Over, Joseph Cracked Him Square in the Face with the Butt of His ‘03 Springfield.

Just prior to the battle, another remarkable event unfolded. Sgt. Maj. Jacob Vouza, a retired policeman from the Native Constabulary, crawled to the lines of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines. While trying to ascertain the movements of the Japanese, he had been captured and tortured when he refused to tell them information concerning the Marine positions. Sliced with swords and bleeding profusely from his wounds, he was seriously injured. It was a miracle that Vouza made it to safety. Before going to the hospital, the native scout informed Pollock of the enemy’s plan to attack. For his bravery, Vouza was awarded the Silver Star by the U.S. government and the St. George Medal by the British military.

As darkness fell, Ichiki’s infantry began its march toward the Tenaru (Ilu) River. The inky blackness concealed the advance of the Japanese, and they arrived there several hours later without being detected. Hearing movement, however, two Marines occupying listening posts squeezed off several rounds before withdrawing from their holes to tell Sergeant Anthony Conti that they heard noises. Conti immediately told the officer on watch, but his information was dismissed. Even the 1st Marine Division after-action reports stated, “Neither fact was considered of particular significance as minor affrays with small enemy parties were of almost nightly occurrence.” Nevertheless, Conti apprised his men to be wary and keep vigilant.

P

rivate John L. Joseph from George Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines was amazed to see an apparition rise from the river. The ghostlike figure was in fact a Japanese soldier who crawled toward Joseph’s fighting hole. As the enemy rifleman peered over, Joseph cracked him square in the face with the butt of his ‘03 Springfield.

Sporadic rifle and machine-gun fire erupted along the line as Ichiki’s main force made its way toward the sandbar. Astonished that the Marines were entrenched this far from Henderson Field, Ichiki nonetheless told the 2nd Company, led by Captain Tetsuro Sawada, to eliminate these emplacements. The fact that the leathernecks knew he was present did not deter Ichiki in the least. He was adamant about certain victory and would still attack even though he was outnumbered.

At 0200 hours, August 21, a Marine let loose a green flare bathing the landscape in an eerie light and creating a surreal atmosphere. Before them was a horde of enemy soldiers crossing the sand spit. Many leathernecks were dumbfounded at the lack of discipline among the Japanese. “We could hear them walking along the beach towards us, and jabbering,” said Private Richard W. Harding. “They didn’t even have scouts out.”

The riflemen held their fire until the Japanese were halfway across. Then the entire line erupted with rifle and machine-gun bursts. The 37mm cannon barked canister that produced gaping holes in the enemy’s formation.

Elsewhere, Corporal Dean Wilson aimed his BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) at the onrushing enemy. When the NCO attempted to fire, all he heard was a click—the weapon has misfired! The young Marine quickly began swinging a machete and within seconds had disemboweled three Japanese soldiers.

As the fighting raged, Lt. Col. Pollock sent the 1st Platoon of George Company, led by Lieutenant George Cordea, to seize several key positions that had fallen to the Japanese. The young Ohio native split his platoon into three squads. He took one group to Hell’s Point. Sergeant James Hancock maneuvered his way to a 37mm cannon emplacement, and Sergeant Charles Spakes went to the spit and established a blocking position to cut down retreating enemy soldiers.

While maneuvering his men, Cordea was struck in the arm, but he remained with his platoon. Digging into the sand on the spit, the riflemen kept up a constant stream of fire to harass the enemy. The Japanese, in turn, showered the infantrymen with machine-gun fire. For his bravery, Cordea was awarded the Navy Cross. His citation read in part: “His outstanding leadership, determination and inspiring fortitude throughout the engagement were largely instrumental in stopping the most serious enemy threat.”

Despite pleas from one of his company commanders, Ichiki was determined to press the attack. He ordered his 1st and 3rd Companies, augmented by the Engineer Company, to outflank the Marines. Just prior to the assault, however, he decided against that plan and instead had his 70mm cannon and eight automatic weapons from the 2nd Machine Gun Company brought up to smash the leatherneck emplacements.

Ichiki’s battalion howitzers sent round after round crashing into the Marine lines. The leathernecks responded with 75mm cannon fire from the 3rd Battalion, 11th Marines that landed precariously close to the 1st Marine perimeter. Colonel Cates requested that the guns send in a few shells on the eastern bank of the river. His gamble paid off as enemy soldiers had massed there for another try at overrunning his lines and were quickly dispersed when the rounds sent them scurrying for cover.

Throughout the night, Ichiki’s companies were decimated. These setbacks, however, did not sway his opinion. He remained resolute about taking the Marines’ positions. He ordered what was left of his 4th Company and volunteers from the remainder of his other three companies to execute a flanking maneuver to destroy the Americans.

This provisional rifle company moved on the Marine left flank by walking waist high in the water along the shoreline. Unfortunately, like Ichiki’s other schemes, this one failed miserably as well. The .30-caliber rounds from the water-cooled Browning machine guns and the deadly accuracy of the 75mm shells rained death and destruction upon this group, and soon the Japanese were cut to pieces.

Dawn finally greeted the weary Marines on August 21. The bright crimson sun that rose that morning displayed the horrible bloodbath that had transpired all night. The mutilated bodies of hundreds of enemy soldiers littered the area in and around Hell’s Point. Despite this ghastly scene, the Japanese did not retreat. Had they renewed their attack in daylight, however, they would have been slaughtered by the unending Marine rifle and automatic weapons fire.

Ichiki was still firm about driving out the Americans and getting as close to the airfield as possible. Because of the accurate stream of the Marines’ small arms fire, however, what remained of Ichiki’s command had no alternative but to hunker in and wait for darkness before they resumed the assault.

The Marines had other ideas. Colonel Cates held a meeting at his CP (command post) to decide on a plan to deliver the decisive blow against Ichiki. “We aren’t about to let those people lay up there all day,” said Colonel Gerald C. Thomas, the division operations officer. Cates nodded in agreement: “We’ve got to get them out today.”

Also present at the conference was Lt. Col. Lenard B. Cresswell, commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines. It was decided to send Cresswell’s men upstream, have them cross the Tenaru (Ilu), and assault in a northwesterly direction along the right bank of the river. This would place him on the enemy’s rear and left flank. Joining Cresswell would be a platoon of M3A1 Stuart light tanks under the leadership of Lieutenant Leo Case from Company B, 1st Tank Battalion.

“Leave Us Alone. We are Too Busy Killing Japs.”

By mid-morning three of Cresswell’s rifle companies had pushed northward while Company D advanced to the north but along the river. Lieutenant Nick Stevenson’s Charlie Company encountered a platoon-size force of Japanese near Block Four Village. While attempting to outflank the enemy, the Japanese soldiers charged the Marines. With their bayonets flashing in the morning sun, the group was mowed down by a broadside of small arms fire. Meanwhile, the other pair of companies continued their movement, squeezing the Japanese in the triangle of land on the east bank of the Ilu.

As the afternoon wore on, four of the light tanks pushed over the sandbar to engage Ichiki’s men. Belching rounds from their 37mm cannon and .30-caliber machine guns, the lightly armored vehicles flushed out the enemy troops concealed in the grove.

In his classic account, Guadalcanal Diary, author Richard Tregaskis witnessed the deadly duel: “It was fascinating to see them bustling amongst the trees, pivoting, turning, spitting sheets of yellow flame. It was like a comedy of toys, something unbelievable, to see them knocking over palm trees, which fell slowly, flushing the running figures of men from underneath their treads, following and firing at the fugitives. It was unbelievable to see men falling and being killed so close, to see the explosions of Jap grenades and mortars, black fountains and showers of dirt near the tanks, and see the flashes of explosions under their very treads. We had not realized there were so many Japs in the grove. Group after group was flushed out and shot down by the tanks’ canister shells.”

With no antitank weapons, the Japanese were forced to stop the tanks by utilizing anti-tank mines and grenades. Ichiki’s men took heavy losses attempting to halt the Stuarts using these primitive means. Case’s “steel beasts” were ripping into the enemy when he received word from Cates to move back. Engrossed in his work eliminating the Japanese positions, Case snapped, “Leave us alone. We are too busy killing Japs.” For hours the deafening sounds of automatic weapons fire permeated the air.

Miraculously, several men survived the onslaught. One sergeant, Sadanobu Okada, remained motionless as a pair of Stuarts neared him. The lead vehicle passed over him, but he escaped injury because he was shielded by the enormous root of a coconut tree. He stayed in this position until nightfall, when he slipped away.

Other members of Okada’s unit were not so lucky. Numerous Japanese fled to the ocean only to be cut down by the Marine rifle fire. Other enemy infantrymen made their way to the east and south. But, they too, were killed. Wildcat fighters from VMF-223 patrolled the beach area, gunning down escaping Japanese with their M2 12.7mm Browning machine guns. By late in the afternoon of August 21, the Battle of the Tenaru River was finished.

The final demise of Colonel Ichiki is still shrouded in obscurity. One account says he committed hara-kiri after putting a torch to his regiment’s flag. Another possibility is that he was killed during mop-up operations after the majority of the fighting had ceased. The few enemy survivors, however, insist he was lost leading his men in a charge across the sand spit.

Regardless of how he met his end, Ichiki’s plan to annihilate the Marines was a disaster. He thoughtlessly sent his men into combat knowing he was outnumbered nearly three to one. He also attacked the leatherneck positions in the Lunga area knowing they were well entrenched there. As the Marine Corps history states: “Ichiki’s mission was suicidal in concept, execution, and outcome.”

When it was over, nearly 800 Japanese were massacred and only 15 were taken prisoner. The Marines suffered 34 dead and another 75 wounded. Vandegrift’s men also snared several 70mm guns, nearly two dozen Nambu machine guns, another 20 mortars, a dozen flamethrowers, 700 Arisaka rifles, plus a variety of other weapons and ammunition.

When news of the slaughter of the Ichiki detachment reached headquarters, one Japanese general commented, “I think it’s a false report.” When the news was confirmed, the Japanese officers present were in total disbelief. The invincibility of the mighty Imperial Army had been shattered. The “haughty, effeminate and cowardly” Americans had dealt a severe blow to the morale of the Japanese fighting man.

For the Marines, it was also a learning experience. General Vandegrift penned a letter to the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Maj. Gen. Thomas Holcomb, in which he wrote, “General, I have never heard or read of this kind of fighting. These people refuse to surrender. The wounded wait until men come up to examine them … and blow themselves and the other fellow to pieces with a hand grenade.”

The Battle of the Tenaru (Ilu) would set the stage for combat in the Pacific Theater—bloody and unforgiving. As Brig. Gen. Samuel B. Griffith commented in his book The Battle for Guadalcanal, “But there was something more fundamental involved here than action taken on the basis of poor information, a reckless and stupid colonel, dedicated soldiers, and a disparity in weapons. This was “face.” Once he committed his sword, Ichiki must conquer with it or die. This was the code of the Samurai, ‘The Way of the Warrior:’ Bushido.

“For their part, the Marines had learned one lesson they would not forget. From this morning until the last days of Okinawa, over two and a half years later, they fought a ‘no quarter’ war. They asked none for themselves. They gave none to the Japanese.”

Al Hemingway is a Vietnam veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History and resides in Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments