By Richard Rule

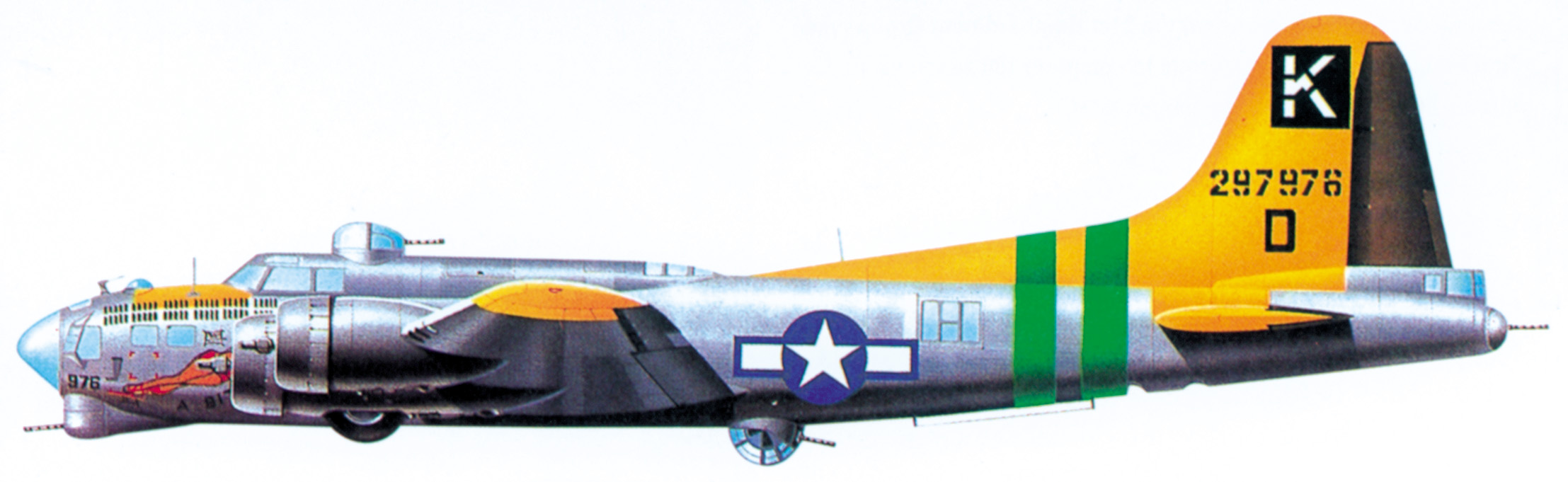

In early 1942, the U.S. Eighth Air Force arrived in England firmly entrenched in the belief that continuous and accurate daylight precision bombing was the only way to decisively crush German industrial capacity. U.S. Army Air Forces commanders recognized that these daylight operations were high-risk affairs but were confident that large formations of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, equipped with the remarkably accurate Norden bombsight, would reap more rewards than the nighttime area bombing strategy adopted by the British.

As the American daylight campaign gained momentum, the Luftwaffe reorganized and deployed well over 600 fighters in depth along the routes regularly traveled by the bomber streams. Luftwaffe pilots, having studied the B-17s, began to engage the bombers from head on rather than persevere with rear attacks against which the Fortresses had impressive armaments. It was a radical departure from the conventional tactics of the time, but it worked.

The Sheer Folly of Daylight Bombing Raids

The belief that B-17s flying in tight, self-defending combat box formations could survive without fighter protection was quickly shown to be sheer folly. With bomber groups disintegrating at an alarming rate in the face of determined fighter attacks, even devoted advocates recognized that daylight bombing was at the crossroads.

In response to this growing Luftwaffe menace, the Combined Chiefs of Staff initiated a directive code-named Pointblank, which made the destruction of the German fighter arm a top priority. In conjunction with its British allies, the Eighth Air Force was to now focus its efforts on undermining Luftwaffe fighter strength in the air by targeting its production and supporting industries on the ground. Despite the ongoing problem of inadequate fighter protection, an intense short-term offensive dubbed Blitz Week was launched.

Massive formations of B-17s were committed to a five-day period of daylight missions against high-priority industrial targets inside Germany. Expectations had been high, but on each successive mission fewer aircraft were coming back. When the raids finally concluded, a staggering 87 bombers had been shot down and nearly 50 others badly damaged or written off. The sacrifices of Blitz Week had made little impression on German fighter capacity, but the crippling losses had shaken the Eighth Air Force to the core and pushed the aircrews to breaking point.

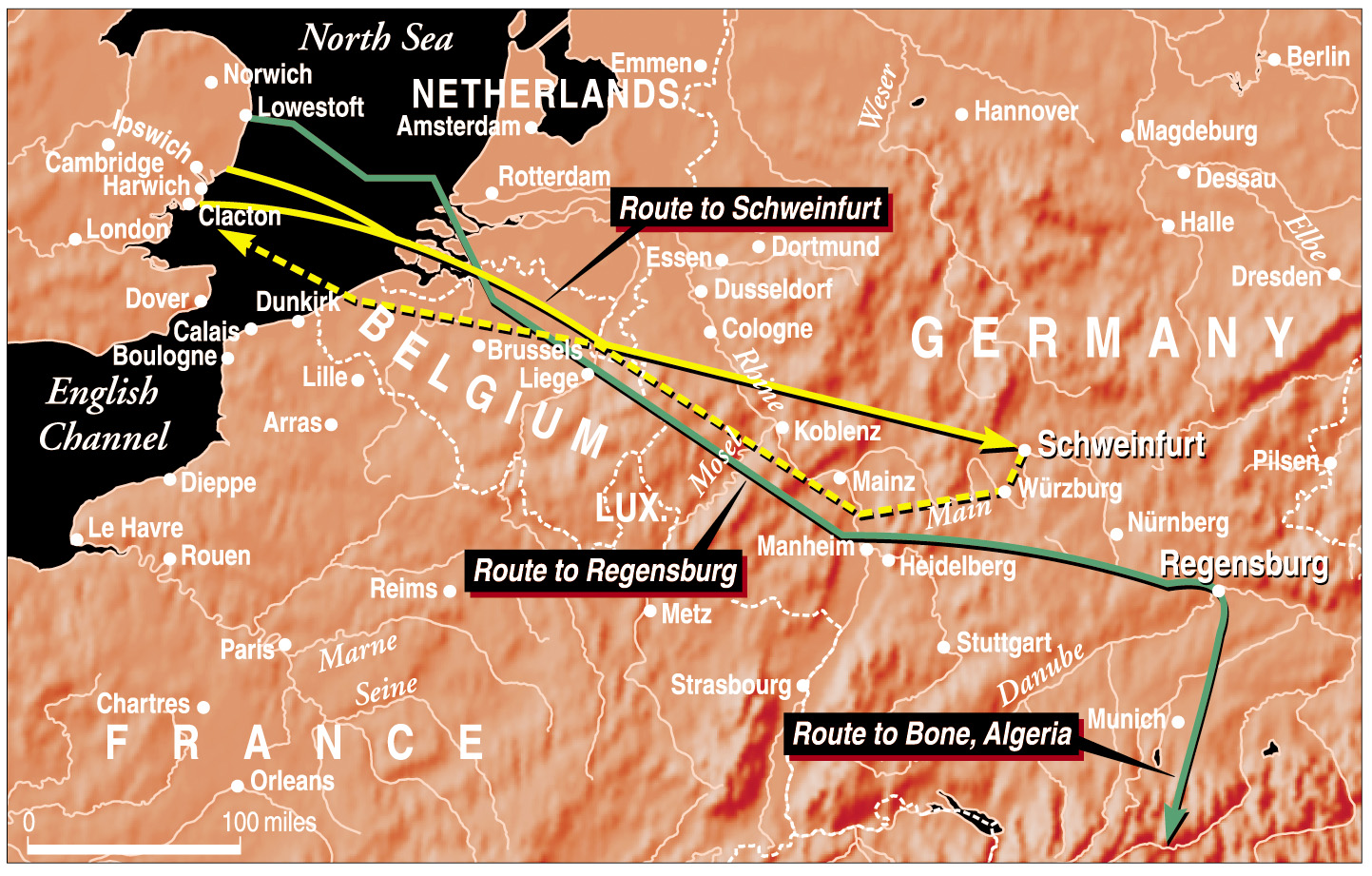

With the future of daylight operations now in serious doubt, American bomber commanders were desperate to deliver something bigger, something more dramatic to shore up wavering support in London and Washington. Refusing to take a backward step, the Eighth Air Force planning staff laid the groundwork for the largest, most daring raid yet contemplated by the USAAF in Europe. In an incredibly ambitious undertaking, the 4th Bombardment Wing would attack the major Messerschmitt aircraft factory at Regensburg followed minutes later by an even larger raid by the 1st Bombardment Wing against the ball bearing facilities in the picturesque town of Schweinfurt.

at fields in Africa.

Plans Made for a Simultaneous Attack on Two Targets

Intricate planning aimed at coordinating the timing of the two formations to ensure the raids occurred simultaneously. With so much at stake, little was being left to chance. The toughest opposition was expected between the coast and approximately halfway to their respective targets. From this point on, little fighter opposition was anticipated. In truth, no one really knew what the bombers would confront in the heart of the Reich. No one had been there in daylight.

To minimize the exposure to fighters, the Regensburg force would not return the way it came as the Germans would expect, but instead fly on to bases in North Africa. These planes were expected to take the brunt of the German fighter defenses on the journey in, allowing the Schweinfurt groups following close behind to slip through while the fighters were on the ground refueling. Their hardest fighting would be during the journey home. It was hoped that each bombardment wing would have to face the full might of the Luftwaffe only once.

The risks involved with these concurrent raids were enormous, but comments by Major Lewis P. Lyle probably encapsulated the views of most senior officers within the Eight Air Force at that time. He noted, “It was obvious we had problems [and] that we might have to give up daylight bombing. We just had to pull off a big one. It was going to be a put-up or shut-up job [and] Germany was the place it had to be done.”

The final draft of what was to be the first real test of the deep penetration daylight theory was completed by August 2, 1943, and reluctantly approved at Eighth Air Force headquarters by its commander, Maj. Gen. Ira C. Eaker. While the soft-spoken Texan recognized the immeasurable importance of the targets, he bitterly opposed the raids, believing his battered forces were not yet ready for a two-pronged operation of such magnitude. The powers in Washington, however, were impatient to step up the strategic bombing campaign and made it clear to General Eaker that the mission would proceed as soon as weather conditions were suitable.

A Break in the Weather Sets the Plan in Motion

Days of heavy clouds and fog over the targets frustrated American plans, but finally, on August 16, meteorologists reported a weather window of opportunity for the following day. Without hesitation, the wheels were set in motion. Airfields came alive during the afternoon and evening as industrious ground crews loaded bombs, filled fuel tanks, and ran up engines at the dispersals. The crews had known for days that something big was in the wind, and the sudden activity around their aircraft was a sure sign that they would be going the following morning—but where?

On August 17, most of those scheduled to fly the two missions were awakened at 2 am for breakfast before heading to their respective briefings. An officer with the 100th Bomb Group recalled that inside the briefing tent “everybody had been chatting away and horsing about a little as usual, but when they pulled the curtain back and revealed that route with the line going out so deep into Germany … there was dead silence for a moment…. We all knew there were going to be a few of us [not] coming back.”

When the destination was announced to the enlisted men, an NCO from the 384th Bomb Group remembered, “A moan went up. Some men stood, cursed, and expressed their bitter dissatisfaction—too deep, so many miles without fighter protection! It was sheer fear that gripped us.”

In some cases, the outburst of rage was so extreme that it took over five minutes to settle the men down. The Regensburg crews, despite their misgivings, recognized that a Messerschmitt plant manufacturing over 300 Me-109 fighters per month was a worthwhile target. Those bound for Schweinfurt, however, took a great deal of convincing that ball bearing factories, although vital to practically all of Germany’s fighting machines, warranted such a dangerous mission.

The details of supporting diversionary raids came as cold comfort to the crews. Their gnawing anxiety arose from the heavy concentration of German fighters they were certain to encounter. They were expected to fly deeper into Germany than anyone had ever gone before in broad daylight and, with the mental scars of Blitz Week still raw, many were convinced they would never make it back.

An Immediate Breakdown in Flight Coordination

With final preparations completed, the mission should have begun at 5:45 am, but most of the airfields were socked in by thick, unbroken cloud cover leading to a 90-minute delay.

Faced with the almost immediate breakdown in the flight coordination, the air force commanders agonized over what they should do. The aircraft of Colonel Curtis LeMay’s 4th Wing would need every hour of daylight and every gallon of fuel to reach North Africa by nightfall. Waiting was not an option. Finally, the 4th Wing, in spite of the fog and clouds, was ordered into the air. LeMay had rigorously trained his pilots in instrument takeoffs. They didn’t like them, but it paid off when at 6:21 am the B-17s began climbing away into the dismal gloom, 90 minutes behind schedule.

The success of the operation hinged on the two missions entering Germany simultaneously to disperse the German fighter strength and confuse the fighter controllers. With fog persisting over the inland airfields, the bombers destined for Schweinfurt would be delayed indefinitely. It was now likely that they would be fighting major air battles on their way in and out.

In a further disruption, the time gap between the two forces was insufficient for the escort fighters to land and refuel. In a hastily revised schedule, the aircraft allocated to this duty were divided between the bombing wings. It was a decision that not only diluted their effectiveness, but also denied both forces the full benefits of the available fighter protection.

In war, when a plan begins to sour it is often at the beginning, and so it would be again. Hundreds of vapor trails were etched across the now clear blue sky as the formations of the 4th Bombardment Wing crossed the Belgian coast near Antwerp. With a fighter escort of Republic P-47 Thunderbolts taking them two-thirds of the way, the bombers had 425 hostile miles of flying ahead of them before reaching Regensburg.

The Luftwaffe Pounces on Coffin Corner

As expected, the flak batteries located in nearly every town situated along their route began hammering away, but the Luftwaffe was yet to make its presence known.

The Germans, however, were not idle. They had tracked the incoming B-17s and scrambled fighters, which were soon in visual contact with the bomber stream. As was their practice, they waited at a safe distance hidden in the sun to study the bomber wings and then pounce on the group flying the loosest formation.

As the B-17s forged steadily on in a southeasterly direction over Holland’s cities and waterways, the P-47s were drawn to a group of Focke Wulf Fw-190 fighters forming up to the north. With the Allied fighters distracted, the Germans waiting in the south seized the opportunity to begin their now classic frontal attacks from the dreaded 12 o’clock high position.

Bypassing the lead formation, the well-trained fighter pilots swept down across the top of the second wing before descending on the last. Without the mutual fire support enjoyed by bombers in the higher formations, the aircraft in the rear and low positions of a combat wing were always the most vulnerable to attack. It was known as “coffin corner” and, true to its name, B-17s began to go down.

Swarms of Me-109s and Fw-190s dived through the Fortresses with guns blazing before climbing, flying back to the front, and coming in again. As the bombers struggled to hold station, the gunners furiously returned fire, their orange tracers criss-crossing the sky seeking out the fighters, an experience the Germans likened to flying through a garden sprinkler.

Even though the B-17s had already passed through the main fighter belt, the attacks continued without respite as fresh fighter units joined the battle. Colonel LeMay, flying at the head of the main formation, was oblivious to the brutal punishment meted out to the smaller second and third combat wings behind him and, in fact, believed that the P-47s had missed the rendezvous altogether. He would bitterly claim afterwards that the only fighters he saw during the entire mission had black crosses on them!

Having exhausted their ammunition and fuel, the ferocity of the German attack slackened as many of the fighters broke off to return to their bases to refuel and rearm. The Allied escorts had performed useful spoiling actions on the run in, despite having lost six bombers, and the P-47s had claimed a number of German aircraft.

The B-17s are on Their Own

All too soon the B-17s were above the Belgian town of Eupen, the point where the fuel-strapped Allied fighters reluctantly turned for home. As the three bomb groups crossed the frontier into Germany, the crews knew they would now be alone for the remainder of the journey to Regensburg and beyond. From Eupen, the Fortresses passed over the vast wooded expanse of the Eiffel, shadowed by a few Me-110s.

Aware that the Germans were always on the lookout for ragged flying, the bomb group commanders began riding the crews to close up their formations. “If you want to live,” one commander told his men, “keep the formation tight.” For a while, the pilots would squeeze in, but fatigue and fading concentration would inevitably see them loosen up again. For many it would be a fatal lapse.

The 50 miles from the German frontier to the Moselle River had been blissfully free of serious fighter attack and, as the minutes slipped by, the men began to feel that perhaps the worst was behind them. They had no idea that their undeviating progress into the heart of the Reich had caught the Germans completely off guard. American bombers had never come this far into Germany, and the astonished German air staffs plotting their path were struggling to gather sufficient forces to challenge them.

The Americans had anticipated only token resistance inside Germany and had the raid taken place two weeks earlier that is all they would have encountered. The vagaries of war, however, would find a new fighter unit established astride the bombers’ route to Regensburg, and they were quickly set on course to intercept the Americans.

Without the protection of their escorts, the bomber crews waited as the German fighters climbed toward them like angry hornets. One of many crewmen perched in the lumbering Fortresses recalled the moment: “I didn’t feel the break in action would be permanent [and I saw] quite a large group spiraling up about two miles out, stacked up in what seemed like layer upon layer in echelon.”

Knowing the bombers were on course to bomb one of their cities reinforced the Germans’ fierce determination to inflict as many casualties as possible. Hungry for success, they once again singled out the rear groups for special and unwanted attention. Displaying nerves of steel, some German pilots pressed their attacks to within 50 yards before breaking off into a half roll or diving away only to come around again. With machine guns and cannon tearing into the bombers, the sky was soon full of battle debris as pieces of aircraft, bodies, half-opened parachutes, and other equipment spiraled dangerously through the air between the B-17s.

A co-pilot watched the main exit door from a Fortress sail past his aircraft, followed a moment later by another object hurtling through the formation. When it came closer, the object turned out to be a man without a parachute “clasping his knees to his head, revolving like a diver.”

By the time the Germans broke off the attack, nine bombers had been shot down and most of the B-17s in the second and third wings were damaged or carrying dead and wounded. They were still flying, but a number of crews had little expectation of making it to North Africa.

A Clear Path to Regensburg

The 30-minute battle had taken the bombers over the Rhine and between the German cities of Mainz, Frankfurt, and Mannheim, but they had finally outrun the Luftwaffe defenses. The way to Regensburg was now clear. As the lead group slowed to allow the battered rear formations to close up, the men in the beleaguered bombers knew that in less than half an hour they would unload their explosive cargo and head for North Africa.

For General Eaker at his headquarters in England, it was an agonizing wait. Once again, his men were flying a very dangerous mission, and once again they would have inadequate fighter support. Behind the scenes, his critics were gathering in ever increasing numbers and, with talk of transferring the Eighth to the Pacific Theater or even pushing carrier plane production ahead of the B-17s, he knew the feasibility of daylight precision bombing hung in the balance.

Eaker was a man of action, but his attempts to join the Schweinfurt raid were thwarted by a blunt instruction from Washington making it clear that if he went, his next flight would be straight back to the United States. Now far removed from the action, the frustrated commander could only wait and hope that most of his bombers made it home.

At 11:40 am, LeMay’s 122 B-17s passed over the initial point (IP) a few miles northwest of Regensburg and fell into a follow-the-leader procession in preparation for the straight and level run to the Messerschmitt complex.

With the aircraft now in the hands of the bombardiers, the 4th Bombardment Wing began dropping its bombs from less than 20,000 feet. The concession in altitude highlighted the importance of the target. The raid lasted 22 minutes, and the departing crews looked down upon the wreckage of the Messerschmitt factory with mixed emotions. They had lost many friends on this mission, but these losses had not been in vain. Reconnaissance photos would later confirm that the factory had suffered extensive damage.

With the rubble of Regensburg now shrouded in an ever-expanding cloud of smoke and dust, the pilots reassembled into their groups and commenced the arduous five-hour flight to North Africa.

The Schweinfurt Group Finally Takes Off

Meanwhile, 500 miles to the west, the 2,300 crew members of the grounded 1st Bombardment Wing were nervously milling around their aircraft awaiting orders. The greatest anxiety was always during that uncertain period between the briefing and takeoff, but on this day the tension was compounded by continual postponements. The lengthy delays had become as unbearable as they were unprecedented.

Finally, conditions improved and at 11:20 am the 222 B-17s began taking to the air, unaware that the Regensburg force was at that moment already well inside Germany. After spending a further two hours getting into their operational formation, the four combat wings comprising the 1st Bombardment Wing crossed the North Sea at 21,000 feet heading for the Dutch coast, 31/2 hours behind Colonel LeMay and his men.

On the other side of the English Channel in the underground combat control center of Germany’s Twelfth Air Corps, it had been a dramatic morning, and it was not over yet. At the same time that they realized the Regensburg Fortresses were in fact destined for North Africa, another even larger U.S. bomber formation was detected starting out from England.

German fighter controllers, having rapidly mustered fighters to ambush the 4th Wing survivors on their return flight, now channeled their efforts into greeting the Schweinfurt-bound Fortresses with the largest home defense force ever assembled.

Every fighter stationed between the Channel and the Rhine, bolstered by an influx of fighter units from the north and south, was refueled and ready for action. Neither the American planners who had sanctioned the delays nor the aircrews themselves could have possibly imagined the trap that was being set for them. The next few hours would see air battles of unimaginable ferocity as a force of between 250 and 300 German fighters, mostly Me-109s, waited in the skies east of Eupen like a spider for a fly.

Soon after crossing the Dutch coast, the lead formation of the 1st Bombardment Wing broke strict field orders and descended 4,000 feet to avoid a threatening cloud mass at between 19,000 and 25,000 feet that lay directly ahead. It was an ill-judged decision that would have grave consequences for the bomber crews in the coming hours. By 2:10 pm, however, the American bomber stream had flown the length of Belgium and crossed into Germany just beyond Eupen. With a mere 48 minutes to Schweinfurt, the crews apprehensively watched as their fighter escorts turned for home.

“It was an awful empty feeling watching our fighters go,” one pilot recalled, “because you knew what was coming next.”

The American Bombers Fall into the German’s Trap

Before the P-47s were even out of sight, a crew member on board one of the B-17s watched with horrible fascination “an overwhelming number of fighters steadily climbing. [It was the most] enemy fighters that I ever saw in my tour.”

The sight of so many German aircraft preparing to attack came as a body blow to the Americans. They had been told to expect little opposition on the way in, yet the sky ahead was teeming with fighters. As the bomber wings closed up in readiness for the inevitable attacks, the older hands knew that without fighter protection they were about to be slaughtered.

The Germans believed the Americans had fatally overstepped themselves and chose to hold back the bulk of their fighters until the escorts had gone. The pilots studying the bomber stream were amazed and delighted to find the three groups of the leading bomber wing flying at a lower level than the others. Not only did it silhouette them against the clouds above, but it would allow the Me-109s to tackle them at their ideal performance altitude. Confident in such huge numbers, phalanxes of 15 or more fighters flying wingtip to wingtip descended out of the sun to mercilessly hammer these leading bomb groups with 20mm cannon and machine guns.

Flying in tight formation restricted the bombers’ ability to take genuine evasive action as successive waves of fighters ripped through them like a scythe. The frontal attacks were a terrifying experience for the American pilots who were literally staring death in the face as the onrushing fighters came straight at them at closing speeds in excess of 500 mph. There was no escape. For some it was easier to just to close their eyes.

None of the crews had ever seen so many German aircraft so close or mounting a more furious attack. There were so many German planes coming in from all directions they risked colliding with one another. To Lieutenant Edwin Frost, a navigator in the nose of a B-17, “It was just pandemonium…. Most [German fighters] were tear assing right through [and] I remember one which seemed to be coming straight at us. Our bombardier accused me of throwing myself down behind him for cover. It was an instinctive reaction. I’d never seen them that close.”

Despite the ferocity and frenzied nature of the German attacks, they were in fact underpinned by a clinical degree of coordination. Experienced Luftwaffe pilots keenly sought out and exploited weaknesses in the formations, or quickly singled out any B-17 that showed visible signs of damage; a feathered or smoking engine rarely went unnoticed for long. For the crippled bombers, which lost height and fell from the protection of the formation, the chances of survival were less than zero. Alone and vulnerable, few got far before being set upon by fighters and hacked out of the sky.

Serious losses had been incurred during heavy action on other missions, but never at the rate experienced this day. Between Eupen and the crossing of the Rhine near Darmstadt, German fighters shot down 21 bombers in the space of 27 minutes, and 210 highly trained airmen went with them.

To Staff Sergeant John Thompson, “It looked like a parachute invasion of Germany. There were planes in flat spins, planes in big wide spins. Planes were going down so often that it became useless to report them.”

With flaming B-17 carcasses leaving a fiery trail across Western Europe, many crewmen were convinced the entire bombardment wing was on the verge of annihilation. Lieutenant Joe Baggs, a bombardier, prayed “that at least we would get to the target. I didn’t think we’d ever get back—that seemed a foregone conclusion—but I did want to get to the target and do what I was supposed to do if only for the sake of those … crews I had watched go down.”

Remarkably, the rear of the force was left virtually untouched as the fighters gave their undivided attention to the three groups of the leading combat wing. Without the threat of escort fighters, up to 25 Me-109s at a time were now coming in line astern using their 20mm cannon with devastating effect. These lethal projectiles could tear through the fuselage of a B-17 as if it were flypaper, as witnessed by Lieutenant P. Perceful, who watched in horror as a bomber was “simply cut in two by the concentrated cannon fire of a German fighter. The Fortress was struck and slowly came apart at the radio room … then both halves twisted and tumbled down and away.”

The death throes of a stricken B-17 were a gut-wrenching sight, for it clearly demonstrated to the others the fate that seemed likely to befall them at any moment. To the Americans trapped like flies in a web, the chaotic air battle raging around them seemed surreal, beyond comprehension, and few were immune to the sheer terror of these relentless attacks. The overpowering smell of burned cordite filled the aircraft as the gunners, with pounding hearts, frantically fired their machine guns, called out incoming fighters, or tried to help wounded comrades.

Finally Through to Schweinfurt

With its numbers dwindling, the defiant 1st Bombardment Wing continued its journey across Germany toward Schweinfurt with the fighters tearing into them the whole way. Finally, after what had seemed like an eternity, the nightmare ended just beyond Frankfurt as the attacks mercifully petered out. The carnage of the previous hour left the crews drenched in sweat and gasping for air as they tried to regain their composure. For many, it had been the most terrifying experience of their lives.

Schweinfurt was only minutes away, and in spite of the brutal fighter assaults, the bombers had made it through to the target. The theory of precision bombing would be severely tested over Schweinfurt because the factories were spaced well apart near residential areas, making them difficult targets for the bombardiers to pinpoint. Nonetheless, at 2:53 pm, the bombers passed over the IP, and three minutes later the 1st Bombardment Wing began to drop its bombs.

The explosive firestorm that swept over the town was awesome, but some who had witnessed the bomb run had doubts about its effectiveness.

As a column of smoke began rising from Schweinfurt, the B-17s reformed into their combat wings and the crews steeled themselves for the gauntlet of German fighters on the way home. After a short flight to the north, they veered westward for the 190-mile journey to Eupen, 68 minutes away. No one doubted that getting out may well prove as tough as getting in.

Their route, for the most part, would be over quiet country, but once the bombers passed the Rhine they would be back in the German fighter belt where things would heat up again. At this stage, the bomber crews finally had luck on their side as the Luftwaffe made its first mistake of the day. With most of its fighters now on the ground rearming and refueling, the Germans incorrectly assumed the Schweinfurt force would wheel south instead of north after its bomb run. The situation was compounded by their inland reporting system, which was inexplicably slow in passing on the bombers’ true position to the fighter units.

A vital opportunity was lost during this early stage of the return flight, but the respite did not last. West of Meiningen the fighters returned—first in small numbers, then in large packs, and the bloodletting started again as 11 more bombers went down.

The day was drawing to a close, but there was still a lot of fighting to be done.

The Regensburg Boys Straggle into North Africa

Meanwhile, as the sun started to set on the coast of North Africa, the crews of the 4th Wing were at last nearing the end of their 11-hour ordeal. Following the departure from the target, three more bombers were shot down, two others crash-landed in Switzerland, while a few more had run out of fuel and ditched in the Mediterranean. The raid itself appeared to have been successful, but the toll on the bomb groups was mounting alarmingly. Thus far, 24 aircraft had been lost.

The entire force was to land at Telergma airfield, 100 miles west of Tunis, but with fuel tanks already on empty, pilots were putting down all along the Algerian coast. An officer at Telergma vividly remembered their arrival: “As the ships were parked, out tumbled the crews, accompanied by a general clamor as some called for help with the wounded.… I was particularly distressed by the sight of one very young sergeant climbing out, leaning his head against the side of his ship, and sobbing convulsively. These people had been through hell—and it showed.”

The Schweinfurt Force Claws its Way Homeward

The Regensburg boys were now on dry land, but found little to smile about. The ground support they had been promised was nowhere to be seen as most of it had moved eastward to follow the war. With the livid Colonel LeMay at his fearsome best rounding up what aid he could muster, many miles away the Schweinfurt force was still clawing its way homeward. The lead elements crossed the Rhine just before 4 pm, still 20 minutes’ flying time from the rendezvous with their escorts at Eupen.

The crews, nearing the end of their tether, desperately searched the sky for signs of the P-47s, and eventually a swarm of black specks became visible in the distance. As the dots grew larger the elation of the Americans quickly evaporated as the aircraft fanned out into the customary head-on attack positions of German fighters. In a matter of moments, the bomber crews again found themselves fighting for their lives as Fw-190s tore through the combat wings. Again, good fortune would smile upon the battered armada, for as the German pilots formed up to come in again, it was they who were in for a nasty surprise.

P-47s from the 56th Fighter Group, using every ounce of fuel from their auxiliary tanks, came into action 15 miles farther inland than any other escort fighter had traveled. Sweeping down from above, the American fighters had caught the Germans completely by surprise, breaking up their next attack. A fierce dogfight ensued around the bomber groups, involving scores of twisting, turning fighters all desperate to gain the ascendancy over their opponents.

The aerial combat raged in a westerly direction from Eupen nearly all the way to Antwerp, with the last and heaviest combat occurring over Leige. Finally, the frenetic air battle broke up when the Germans retired to their bases. Remarkably, only one B-17 was lost during this engagement.

With the worst behind them, the remainder of the bullet-riddled bomber force limped across the North Sea toward England and began touching down at 5:47 pm, with many of the damaged Fortresses landing on the first airfield they could find. No one had ever seen anything like the events of this day. For the ground staff waiting at the bases, the gaps in the formations came as a terrible shock. “When the planes came from behind the horizon,” one recalled, “I counted them. ‘I made a mistake,’ I said to myself, and counted again. I did not want them to be ours, we had sent out so many more.”

Despite Accurate Bombing at Regensburg, Impact Was Minimal

Clearly, the German fighters had enjoyed their most successful outing yet against the Eighth Air Force, but they had not been able to turn it back. Figures vary, but on the Schweinfurt operation alone 36 Flying Fortresses were shot down, 27 were written off, and a further 95 aircraft received varying degrees of battle damage.

On top of the 24 bombers lost by the Regensburg force, a lack of repair facilities in North Africa would see 60 of their aircraft left behind while three more were shot down during the return flight to England. In total, over 40 percent of the 361 aircraft that had undertaken the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission were shot down, written off, or abandoned. Along with these 147 B-17s, the Eighth lost 565 highly trained airmen killed, taken prisoner, interned in Switzerland, or missing.

Perhaps to ease the impact of their appalling causalities, wartime propaganda reported that over 300 German fighters had been shot down during the raids. In reality, the Germans had lost 16 pilots and 47 aircraft to air combat, plus an additional five to accidents.

In addition to the horrendous losses suffered that day, the American crews were bitterly disappointed to learn that the British had cancelled a follow-up night raid over Schweinfurt. Unbeknownst to many of the Americans, the British had, in fact, been ordered to launch a maximum effort of their own against the secret German rocket establishment at Peenemunde.

In the postmission evaluation, the performance of the 4th Wing over Regensburg could hardly be faulted, and the bombers’ spectacular accuracy had even astonished the British. In the wake of the operation, postwar studies indicated the interruption to production cost the Germans up to 900 front-line fighters and destroyed the jigs for the Messerschmitt 262 fuselages, resulting in a considerable setback to the jet fighter program.

Yet, despite the obvious destruction they had inflicted, one great truth of the bombing campaign was in evidence at Regensburg: Looks can be deceiving. Reconnaissance photographs confirmed that all six main workshops were damaged or destroyed along with the final assembly shop and gun-testing range, but when the debris was cleared away, much of the all-important machinery was found to have survived intact. The 500-pound bombs had not been potent enough to destroy them. It was viewed as a successful raid, but German production had only been stalled, not destroyed, and limited manufacturing recommenced within a month.

The Schweinfurt Mission Failed to Deliver a Knockout Blow

Despite the extraordinary efforts of the 1st Bombardment Wing crews, the raid on Schweinfurt failed to deliver a knockout blow. Only three of the 12 groups dropped their bombs anywhere near the target, but mitigating circumstances contributed to the poor results. Altogether, 196 bombers had reached the IP, but it was not the one for which the crews had been briefed. They were originally to have attacked from the east to avoid looking directly into the rising sun, but the delays in England brought about a late change of plans. They would now approach from the west to avoid the glare of the setting sun.

The already difficult task of trying to pinpoint multiple targets was compromised by these last-minute changes to the bombing plan, compounding the confusion and congestion caused by the very large bombing groups.

The Schweinfurt raid certainly curtailed production capacity in the short term, but it failed to have a significant long-term impact as stockpiled bearings were drawn upon to make up the shortfall. As occurred at Regensburg, most of the machinery was simply dragged from the wreckage and swiftly put back into operation. Surprisingly, September’s quota of ball bearings exceeded that of August’s. The USAAF, supported by large resources in men and machines, was willing to accept high casualties in pursuit of victory, but in this instance many felt the bombing results hardly justified such unsustainable losses.

Despite the horrendous losses incurred by the Schweinfurt-Regensburg forces, the hard-earned lessons from these missions seemed to have been quickly forgotten. On October 14, 1943, the Eighth Air Force once again bombed Schweinfurt without escorts and once again absorbed brutal punishment, losing another 60 bombers.

The martyrdom of the Schweinfurt raid “assumed proportions of an American bombing epic,” but in reality it served only to demonstrate the failings of the self-defending bomber strategy. With two-thirds of all Germany’s fighters now deployed in the West, the skies over Western Europe appeared destined to remain a killing ground for the Luftwaffe.

The lack of a long-range fighter remained an insurmountable obstacle until the arrival in numbers of the magnificent North American P-51 Mustang in early 1944. With a bomber’s range and a fighter’s performance, the Mustang could at last provide the bombing groups with fighter protection all the way to and from their targets.

It was a defining moment in the air war. With American bomber fleets now roaming the skies of Occupied Europe at will, the Luftwaffe would finally lose control of its own air space. It would never win it back.

Richard Rule writes from his home in Heathmont, Victoria, Australia. A veteran of the Australian Army, he works in sales management, enjoys fly fishing, and has written several books.

My mother, was a child growing up in Regensburg during WWII and told my siblings about the air raid on the Messerschmidt plant 8/17/45, when we were kids. The plant was near the Danube River and her school was on a hill overlooking it. The doors were locked from the inside and as the bombs were falling, workers were breaking windows to flee the fires. People had no arms, legs, were on fire and other macabre images.

After the war, her younger brother was killed by a grenade lobbed his direction by another child, while playing among the rubble in the city.

One of the planes my grandfather flew during WWII was a Heinkel 111 Zwillig.