By O’Brien Browne

Operation Gericht—which means “judgment” or “tribunal”—was the German offensive of the Battle of Verdun. The operation was the brainchild of Erich von Falkenhayn, chief of the German general staff as the year 1915 was coming to a close. Descended from a long line of Prussian military men, he was a cold, rational, distant man. A personal favorite of Kaiser Wilhelm II, Falkenhayn was faced with a problem: The war against France, Belgium, and Britain was not going as planned by Prussian strategists. Originally, according to the intricately developed Schlieffen Plan, the German armies were to have sliced through Belgium and into northern France, sweeping the French army and its British allies before it in an irresistible strike at Paris. But the Belgians had fought valiantly, France’s Russian ally had invaded the eastern German Empire, and the French had smashed into the exposed flank of the German army on the River Marne, halting its drive. Both sides had dug in, and the war of movement—and German dreams of a lightning victory—vanished into the sullen horror of trench warfare.

Faced with this stalemate, Falkenhayn sat down in December 1915 to write a long memorandum to the Kaiser. The key to winning the war, argued the chief of staff, lay in the West; Russia, disorganized and unstable, could be dealt with later. France was the crux, and knocking France out of the war would bring the British to the peace table.

“Within our reach,” Falkenhayn’s memo read, “behind the French sector of the Western Front there are objectives for the retention of which the French General staff would be compelled to throw in every man they have. If they do so the forces of France will bleed to death—as there can be no question of a voluntary withdrawal—whether we reach our goal or not.” Verdun was the site picked for this grim hemorrhaging operation, code-named Operation Judgment.

Did the Operation Judgment’s Objectives Justify the Intensity of the Assault?

The choice of Verdun was a natural for Falkenhayn’s battle of attrition, for here were located probably the strongest fortified systems in the world. More than mere forts, the formidable defenses symbolized the French army, French honor, and independence—indeed, France itself. Falkenhayn was right in arguing that a German victory here would be intolerable to the French, a moral and psychological blow at the country’s heart. In defending it, Falkenhayn believed, they would sacrifice their army and then have to sue for peace.

As for the forts themselves, the German army felt certain that they would be easily pulverized by heavy artillery—the huge Krupp-made 420mm “Big Berthas” that had leveled the “indestructible” Belgian forts of Liège and Namur at the beginning of the war. Taking the Verdun forts, Falkenhayn reasoned, would present no great problem. What he could not foresee, however, was how determinedly the French would fight to defend them.

A sophisticated court insider, Falkenhayn carefully designed his plan to appeal to the Kaiser’s enormous vanity: The official orders for the attack were released on January 27—His Majesty’s birthday—and the Kaiser’s son, Crown Prince Wilhelm, would lead the V Army in the attack.

A major flaw in Operation Judgment, however, was its lack of goals. The target of what was to be the greatest German military operation up to that time was not to break through the Allied lines; it was not even to capture the great forts themselves. At the most, winning the Battle of Verdun would protect important German railway lines 20 kilometers away, but even this could not justify the intensity of the assault. Falkenhayn himself was vague on just what his forces were supposed to accomplish other than destroying the French army by attrition and then, perhaps, seeing what opportunities presented themselves afterward. His thinking was so broadly strategic that he utterly disregarded the details. To this day, military historians are puzzled by what Falkenhayn’s real objectives were.

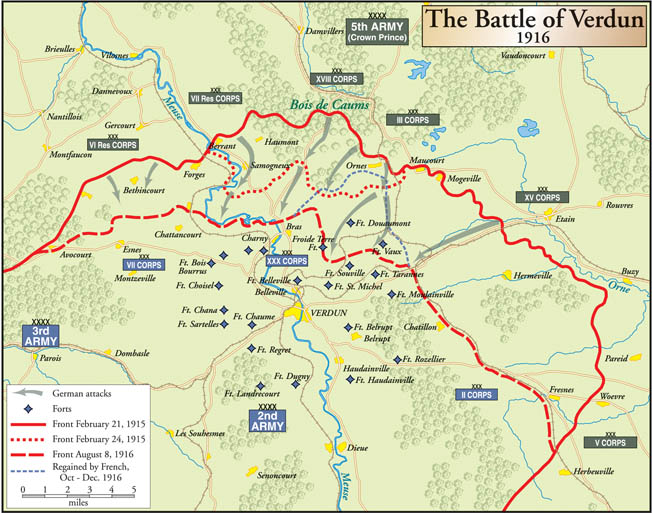

Not having seen Falkenhayn’s memo to the Kaiser, the Crown Prince and his chief of staff, General Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, set about devising a real plan of attack centered on the capture of the Verdun forts. This was to be a two-pronged pincer movement across the western and eastern banks of the Meuse, designed to overrun the forts and, it was hoped, develop into a breakthrough of the lines and a rolling up of the enemy’s forces.

Secretive, indecisive, and loath to take risks, Falkenhayn vetoed this plan of action. Capturing the forts, perversely, did not fit his idea of a drawn-out “bleeding-white” operation. The actual fall of the forts would make the process shorter, and thereby—in Falkenhayn’s cold logic—inefficient. Significantly, Falkenhayn never explained his idea to the young and inexperienced Crown Prince, possibly because he calculated that few would willingly fight in such a macabre battle.

In the end, Falkenhayn limited the Crown Prince and Schmidt von Knobelsdorf’s plan to an attack only on the Meuse’s eastern bank, and thereby weakened the German army’s striking arm. With shrewd calculation, Falkenhayn promised further reserves as the battle progressed, although these were to be kept under his strict control. Thus, the Crown Prince’s V Army believed its target was the forts, while Falkenhayn kept to his original idea.

France Unintentionally Aided the German Effort by Weakening Their Forts

Verdun consisted of a network of more than 20 large and small sunken fortresses, with Fort Douaumont, built on a hill 1,200 feet high, forming the anchor of the defense. Located on the River Meuse, the line of forts formed part of a large salient bulging into the German lines, which meant that the Germans could fire on French positions from three sides. It would have been sound strategy for the French to abandon the forts and thereby shorten their lines. Politically, however, such a move would have been inconceivable. French public opinion would have never supported voluntarily surrendering at the Battle of Verdun, as the city was the emblem of French military might and national honor.

Despite the symbolic importance of Verdun, the French had done much to aid German battle plans by weakening the forts. Having observed the relatively easy fall of the Belgium fortresses, the rotund and somnolent French commander-in-chief, General Joseph Joffre, had grandly declared forts to be useless. Subsequently, the fortresses of Vaux, Douaumont, and others were stripped of men and weapons that were then sent to more active fronts. Only one thin line of trenches was dug to defend the forts, now manned by skeleton crews and used as depots for housing men and materiel. No political fool, Joffre did not inform the French public about his decision to castrate these symbols of France’s pride and power.

Meanwhile, the Germans were pushing ahead with characteristic thoroughness. As in nearly all Great War battles, the attackers amassed an impressive lineup of artillery: more than 542 heavy guns, 17 305mm howitzers, 13 “Big Berthas”—which were capable of hurling a 1-ton shell for several miles—plus mortars and medium and light guns. The Germans concentrated 150 guns to each mile on an 8-mile front. A total of 140,000 men dispersed among 72 divisions faced an ill-prepared, paltry French defense of only 270 guns and 34 divisions. Also, German aircraft were sent aloft to prevent enemy observation planes from photographing the army’s preparations, a job helped by foggy, rainy weather.

Falkenhayn’s plan of attack was novel: a short, sharp bombardment on a narrow front to kill the defenders and wipe out their trenches, followed by the German infantry—not dashing themselves in suicidal waves against the enemy, but advancing in small groups and using the contours of the ground, tactics that would later be perfected by the stormtroopers of the great German offenses of 1918. The infantry’s main role would be to “mop up” the defenders, although it was widely believed that there would be nothing left to mop up after the storm of shells ceased.

The Battle of Verdun was the Largest Attack History Had Ever Known

Zero hour for the Battle of Verdun was set for February 12, 1916. The night before, German officers and enlisted men readied their weapons and stared with sullen tension at their target across the fields of barbed wire. The great killing machine of the German army was poised to unleash itself in the largest attack history had ever known.

But nothing happened. That night, a powerful snow blizzard slammed into the area with a torrent of whipping winds, freezing rains, and sub-zero temperatures that did not let up for nearly a week, thus postponing the attack.

While German soldiers crouched in their bunkers and trenches and artillery gun sighters peered helplessly into the swirling white soup, the French, alerted at last that something was indeed up, began to rush in reinforcements. Even slow-moving General Joffre arrived on the scene. This storm saved Verdun, and perhaps France as well.

When visibility improved on the 21st, the message was passed down from V Army headquarters: Attack. Operation Judgment was launched when a giant 15-inch Krupp naval gun 20 miles away belched a huge shell that arched through the sky and exploded inside the town of Verdun. This was the start of nine hours of hell.

The earth heaved and erupted as thousands of explosives crashed downward. Forests disappeared into showers of splinters, trenches vanished, shell holes opened up like black gaping mouths. It was, said French Corporal Stephane, “a storm, a hurricane, a tempest growing ever stronger, where it was raining nothing but paving stones.” More than two million gas, shrapnel, and high-explosive shells were fired into the narrow 8-mile front, falling, one historian has estimated, at a rate of 100,000 an hour, 1,700 a minute, 30 a second.

The bombardment reached a manic cres- cendo at around 3:30. Half an hour later the German infantry rose up, a field-gray wave surging in from the Meuse’s east bank, stumbling across the torn lunar-like landscape. They expected to find no one living.

They were wrong. Although the French had suffered many killed and wounded and their thin trench lines had been wrecked, as soon as the tempest of shells had ceased they emerged from their dugouts and foxholes, faces blackened, uniforms covered in filth and ripped to shreds, and began firing upon the advancing Germans, taking them by surprise. Incredibly, the thick-walled underground forts had not been destroyed and, from their concrete port holes and steel turrets, machine-gun and artillery fire spat deadly streams of lead.

Although totally outnumbered and dazed by the bombardment, the French fought with fury. Lieutenant Colonel Emile Driant, over 60 years old and a famous military writer, commanded the units facing the German onslaught. A rifle clutched in his hand, he courageously directed the defense until he was struck down by a bullet to the head. His valiant death assured his immortality as the first hero of Verdun.

The Germans Advanced Only 2 Miles and Already Took Almost 3,000 Prisoners

As the day came to a close, it became apparent that Falkenhayn had been right about one thing: The French would fight to the last man to defend Verdun. The unexpectedly stubborn resistance halted the German attack far from its goals, although many prisoners and guns were captured. That evening the bombardment resumed, followed by a German strike at Fort Douaumont, and the use of a frightful new weapon: the flame-thrower. But each inch of ground was dearly paid for in lives, for the French launched brutal and continual counter-attacks, making Verdun one of military history’s few examples of the defense losing more men than the offense. By the third day of the battle, the Germans had advanced only 2 miles and had taken 3,000 prisoners. And the horror had just begun.

The Verdun battlefield quickly turned into a surrealistic landscape of gothic dimensions—it is utterly impossible for modern generations to imagine the ghoulish conditions under which both Germans and French fought. The sky was a continual gray and heavy with smoke. At night it was lit up by tongues of red, yellow, and icy white as artillery pumped round after round onto the battlefield. The entire area was pocked by millions of shell holes—some large enough to accommodate a house—filled with foul blackened water, sucking pools of mud, broken equipment, and the dead and dying. The high-pitched scream of horses rent the air, and everywhere was the flash of guns and the shriek of shells.

“Anyone who has not seen these fields of carnage,” wrote a French soldier of the 65th Infantry Division, “will never be able to imagine it. When one arrives here the shells are raining down everywhere with each step one takes but in spite of this it is necessary for everyone to go forward. One has to go out of one’s way to not pass over a corpse lying at the bottom of the communication trench. Further on, there are many wounded to tend, others who are carried back on stretchers to the rear. Some are screaming, others are moaning. One sees some who don’t have legs, others without any heads who have been left for several weeks on the ground….”

Flying over the battlefield, Edwin Parsons, an American volunteer for France fighting with the famous Escadrille Lafayette, noted: “Nature had been ruthlessly murdered. Every sign of humanity had been swept away. Roads had vanished, and forests were fire-blackened stumps. Villages were gray smears where stonewalls were tumbled together. Only the faintest outlines of the great forts of Douaumont and Vaux could be traced against the churned-up background.”

The French 520mm shells and German 420s were as large as a man and weighed up to a ton each: Shells such as these accounted for three-quarters of all casualties in World War I. A sharp ripping or cracking noise signified when one had been fired from far across the lines. As they neared, each shell had its own distinctive sound which the experienced soldier could identify—some came with a whiz-bang, others with a lethal woof-woof, some roared, others screamed.

Soldiers Were Trembling, Crying, and Twitching With Fear

The terror of being shelled was not just in the explosion, but in the waiting for it, hearing the crack from some hidden gun miles away, the vault across the lines, and the sudden locomotive rush as it dropped to earth. Crouching against a trench’s walls, shoulders hunched, lips bloodless, the soldiers waited as their nerves frayed like a breaking rope. During these hellish minutes, nearly every soldier suffered from some form of spontaneous trembling, crying, twitching, severe constipation, or diarrhea.

Then the tremendous force of the explosion. If the concussion did not rupture a man’s internal organs or turn his brain into a gray mush, its sizzling chunks of jagged shell casing ripped into his too-soft flesh, tearing, amputating, killing. Barrage firing, of the type seen at Verdun, meant that a virtual nonstop rain of shells fell for hours or days or weeks at a time. It drove some mad, terrified all. One British soldier recalled, “After a thunderous crash in our ears, a young boy began … screaming for his mother with a wail that seemed older than the world.… We shook him and cursed him and even threatened to kill him if he did not stop.” The shaking brought him back.”

Artillery bombardments were not the only things the men feared. Machine guns hurled bullets at the rate of more than 550 a minute, snipers picked off the unwary, trench mortars and grenades drove steel splinters into bodies, and chlorine and phosgene gas arrived in low, noxious clouds. Denis Winter, author of the superb book Death’s Men, tells us that phosgene gas, “smelling faintly of moldy hay and producing a slight sensation of suffocation,” was particularly dreadful, causing the victim to experience trouble breathing, followed by violent vomiting and a torturous wet death as he drowned in a yellow liquid produced by his own violated lungs.

Life in the trenches was equally horrific. Daytime, when the enemy was the least likely to attack—and providing there was no shelling—was dull with routine. Soldiers were kept busy repairing broken parapets, cleaning weapons, eating, sleeping, crushing lice, killing the huge, fat rats that fed on the living and dead alike, or batting away dark clouds of flies. Early morning and the black of night were much more ominous. This was when the men were most nervous—this was the time for enemy raiding parties or dawn attacks. Nevertheless, many preferred the adrenaline rush and heat of battle to sitting helplessly in a hole in the ground.

”Shell Shock”

Although one rarely ever saw a living enemy, there was constant sniping, the odd machine-gun blast fired at head level. In addition to this, mud, foul water, filthy sanitary conditions, and the cold sapped morale, caused lethargy and a vacant-eyed form of soldier’s depression from whence the term “shell shock” comes. Piled onto these miseries was a plague of diseases—frostbite, dysentery, meningitis, trench foot, which often turned into gangrene, pneumonia and, most prevalent of all, venereal disease.

Joys were few and therefore all the more precious: the wine or rum ration and a hot meal lifted shattered spirits. Cigarettes calmed nerves and killed hunger pangs. And those intangible cords that bind comrades together, and which no history can ever adequately describe, helped keep the men going. After all the grand and empty patriotic words had been spoken, every soldier knew he was fighting for one thing: his buddies.

One dreadful reality of Verdun that was to haunt the memories of those who fought there was the sickly-sweet stench of rotting flesh. Because of the intense and virtually unceasing shelling, the small battlefield, and the awesome numbers of men and animals that died there, Verdun was a garbage dump of death. Artillery shells chopped and rechopped bodies; graves were continually ripped open, spilling their contents onto the battered earth to bloat in the sun; heads, feet, arms, and legs lay spewed about—an unspeakable harvest from broken fields. Virtually every inch of ground was occupied by some piece of putrid flesh.

A letter from a French soldier in the trenches near Thiaumont read, “I stayed ten days next to a man who was cut in two; there was no way to move him; he had one leg on the parapet and the rest of his body in the trench: it stank and I had to chew tobacco the whole time in order to endure this torment. …”

“This is not war,” wrote another Frenchman, dug in near Fleury, “it’s a massacre. Oh! when will it end?”

The battle roared on. On February 25, crisis struck the French camp when the great fort of Douaumont fell—and not after a heroic last stand; its capture was more along the lines of slapstick comedy. German Sergeant Kunze of the 24th Brandenburg Regiment and a handful of men cut their way to the world’s mightiest fortress, where Kunze wiggled inside through a small portal and creaked open one of its giant steel doors. With fearless bravery or naive stupidity, Kunze then wandered around the undermanned fort’s interior for several minutes—capturing several surprised Frenchmen in the process—before another handful of German troops arrived on the scene to round up the rest of Douaumont’s small garrison of fewer than 60 men.

Thus the fort fell without a shot. Its capture made headlines around the world and was a great boost to German morale. Contrary to Falkenhayn’s expectations, however, France did not suffer a moral or even political collapse after this defeat. Instead, French commanders launched immediate and bloody counter-attacks to retake the useless fort. The struggle became more embittered. During parts of the Verdun fighting, notes one historian, “German soldiers were killed at the astounding rate of one every forty-five seconds.”

French Troops were Pummeled by Nearly 8,000 Shells a Day

On the 31st the French were again hard pressed when Fort Vaux was besieged. Although pummeled by an estimated 8,000 shells a day, it did not fall as quickly as Douaumont had. Led by the tough and able Major Raynal, the Vaux defenders put up a stiff defense that exacted a high toll for every foot of ground the Germans advanced. But slowly the outlying trenches were taken by the attacking Germans, bottling up Raynal and 600 men inside the fort. Soon its concrete corridors were filled with the dead, wounded, and dying, the latter two suffering horribly from thirst and the relentless, dreadful pounding of the shells smashing down on the fort’s thick roof. By the second day of fighting the Germans, after much cost and sacrifice, had beaten their way into the fort, orange flame-thrower tongues licking out in front of them as pitched battles with grenades, machine guns, and bayonets ensued with ferocious savagery. The hallways were filled with choking clouds of gas fumes, the reek of rotting flesh, and the din and stink of battle.

Raynal held out until June 7, when he surrendered. But really they were not conquered by the Germans, but rather defeated by thirst: Raynal and his men had had no water for over two days. Impressed by the skill and bravery with which Raynal and his troops had fought, the Crown Prince accepted Raynal’s sword in surrender but then gave it back to him.

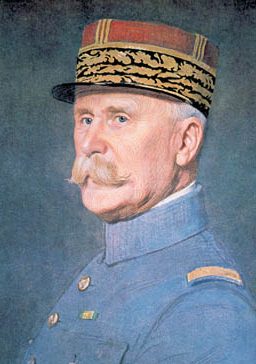

Slowly, Joffre’s languorous mind perceived the danger to Verdun and to France, and he allowed his subordinates to place General Henri Pétain and his II Army in charge. Uttering “On les aura” (“We’ll get them!”)—a line that was later used in a successful propaganda poster—Pétain energetically took control. A superb organizer, he directed the defense and counterattacks and, most importantly, had a supply route constructed by French colonial troops, a massive lifeline of food, men, and equipment transported in up to 3,500 trucks a day from the French base at Bar-le-Duc to Verdun, a journey of almost 50 miles. Known as La voie sacrée—the Sacred Way—it kept the French forces alive, every week dumping 90,000 men and 50,000 tons of supplies into the battle zone.

On March 6, convinced somehow that the French were faltering, the Germans renewed their attack, this time striking along the west bank of the Meuse. By the middle of the month, the battle centered on a hill appropriately named Mort Homme—The Dead Man. The fighting here, as everywhere in Verdun, was horrific. Again, the French did not easily yield and the attack was not successful until the end of May, but at a Pyrrhic loss of life that resulted in no breakthrough for the weary German army, no definite victory. It was, in the end, merely another hill taken at an enormous loss of life. By April 1 French casualties had reached 133,000; the Germans had lost 120,000—and all for nothing: “Conquered” territory could be measured using a scale of less than five miles.

Toward the middle of the month, the Crown Prince had come to believe that the battle could not be won and expressed increasing concern over the terrible waste of life. In high-level meetings he suggested that it be called off. The Crown Prince’s good sense, however, was blocked by a hardliner, General Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, Prince Wilhelm’s own chief of staff. Falkenhayn was by this time indifferent, more concerned about maintaining his position at the Imperial Court than anything else, and growing increasingly nervous about British activity near the Somme River in northern France. Characteristically, he shied away from making a concrete decision on whether the battle should be ended or not. Lacking support from Falkenhayn and even his own father, the Kaiser, Prince Wilhelm’s objections were ignored, and the monstrous and increasingly senseless battle continued.

“Ils ne passeront pas!”

The French were stiffened by their own hardliners, chief among them General Robert Nivelle. Bombastic and flashy, his voice was one of the loudest urging the continuation of the fight and the recapture of the lost forts—an idea in line with Joffre’s thinking. Not to be outdone by Pétain, Nivelle had ended his June 23 Order of the Day with the words, “Ils ne passeront pas!”—“They shall not pass!”—which also found its way onto a government poster. Although able to dazzle the politicians with his confidence and dramatic martial bearing, to his men he was known as a butcher who favored costly attacks against strongly defended German positions.

To relieve pressure on his Verdun army, Pétain asked Joffre to move up the date for a planned joint British-French attack on the Somme. This was done, and the attack was brought forward to July 1. The British, contemptuous of their French ally, had learned little from the five months of fighting at Verdun. The British soldiers left their trenches on a sunny summer’s day, marching in proper parade order directly into the murderous fire of German machine guns—whose gunners were presented with such an orderly and dense target that they barely even had to aim.

The British army suffered 60,000 casualties on the first day alone, the greatest single loss of any army in World War I, and possibly in all history. The poet Siegfried Sassoon, then a second lieutenant with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, called it “a sunlit picture of hell.” The Somme, however, had an immediate effect on the fighting at Verdun. To meet this new threat, Falkenhayn cut off reserves to his armies there, and sent them reduced ammunition shipments.

The fighting continued fiercely throughout the spring and summer, both sides somehow finding the energy to repeatedly lunge at one another, trying to crush each other’s will but both actually caught up in a feverish insanity. The battle had taken on a life of its own. It existed because it existed, according to its own logic. The soldiers themselves even stopped referring to it as a battle to be won or lost; to them it was known as the Fire, the Inferno, the Monster, the Mincing Machine, the Meat Grinder, the Massacre or, simply, Hell. “At Verdun,” wrote German soldier P.C. Ettighoffer with irony, “France was supposed to be bled white. At Verdun, Germany was bled white, too.”

The same line of trenches, the same strips of territory, were conquered and lost again and again. The scorched patch of earth that had once been the village of Fleury, for example, changed hands 16 times during the fighting. With the cutoff of the German reserves, the French now went on the offensive under the aggressive leadership of General Nivelle. Their pointless task: to retake the lost forts. The attacks were duly launched, at horrendous cost to the French. Finally, a Moroccan colonial infantry regiment retook Douaumont in late October; Vaux was recaptured on November 2. A withering attack on December 15, 1916 pushed the Germans three miles back, and it is here that the battle is generally considered to have concluded—in stalemate, exactly as it had begun 10 months before. Only now more than three-quarters of a million French and Germans had been killed, wounded, or captured.

Verdun was likely history’s longest battle. It also has the dubious distinction of having had more men fall per square foot than any other battlefield. To this day, the ground oozes shell fragments and human bones, bullet-riddled sheets of steel, lethal coils of rusting barbed wire, and unexploded shells—jagged mementos of a violent century.

How the Battle of Verdun Ended

Although the French and German armies had pounded themselves to exhaustion at the Battle of Verdun, Falkenhayn had been wrong: The French did not sue for peace. The protracted battles at Arras, Ypres, Champagne, and in the Balkans, the Middle East, and Africa were yet to come. The war was to continue for almost another two years.

The victims of Verdun were not just the men in the front lines. Reputations died as well, and a few consciences, too. Falkenhayn was replaced as general chief of staff by Generals von Hindenburg and Ludendorff, the heroes of the great German victories against Russia. Falkenhayn, however, was later to achieve much success in the German campaign in Romania. After the war, he was heard to comment that he had trouble sleeping at night, so perhaps Verdun had indeed touched a nerve after all.

Joffre was promoted to the figurehead position of chief military adviser to the government, where he could do no more damage to his own army. General Nivelle’s brash and bold talk got him the job of chief of staff. In the spring of 1917, he promised to win the war with a new offensive near the River Aisne against one of the strongest fortified positions in the German lines. Launched in April, it proved so costly in human lives that his troops mutinied, and the cocky Nivelle was relieved of command.

One of the ironies of Verdun is the lessons the French drew from it. For one thing, they mistakenly renewed their faith in fortified positions, which resulted in the building of the Maginot Line in the 1930s. This system of fortified concrete bunkers was supposed to have been France’s wall of protection against Hitler’s Germany. When war came, German motorized divisions—led by men who had also fought at Verdun—easily swept around these anachronisms and overran Verdun in a day. The Battle of Verdun had lasted 10 months in 1916; the Battle of France lasted one month in 1940.

Verdun and the other battles of World War I had sapped the French nation—morally, physically, materially. In this, Falkenhayn’s operation had been successful. By the time of World War II, France had still not fully recovered its immense losses in population and natural resources; the once-rich farmlands of Verdun, for instance, were still so polluted that virtually nothing would grow there. But more than this, France could not muster the willpower to resist the Nazis. The ignominy of the Vichy regime, which collaborated in Nazi atrocities and gashed wounds in the French national psyche that have not healed to this day, grimly illustrates that more than just men had been buried at Verdun.

“Verdun Transformed Men’s Souls”

France’s tragedy is symbolized by General Pétain. One of the few heroes to emerge from Verdun and a man who always cared for the welfare of his soldiers, he was stunned by the dreadful scenes he had witnessed there. In 1940, when German armies again swept into France, the 84-year-old Pétain was summoned once more to save his country. Horrified at the prospect of another meaningless and brutal conflict, his moral reserve drained at Verdun, he became the puppet of the Vichy government. After the war he was sentenced to death by a French court, although this was later transmuted to life imprisonment. Pétain died in 1951.

Half-destroyed during World War I, though never overrun by the Germans, the modern town of Verdun can consider itself fortunate—it still exists. It was rebuilt after the war, unlike the nine other surrounding villages that were literally blasted into nothingness during the battles that raged there during the Great War. Today, only grim stone markers indicate that these villages once existed. “Ici fut Fleury,” reads one plainly. “Here was Fleury.”

The Industrial Age’s ingenuity and creativity had reached full flower in World War I. The firsts to come out of this conflict are impressive: the tank, the development of aircraft and submarines, poison gas, the marshalling of entire societies in total warfare, and the revolutionary use of women in factories and the army. Rarely has one civilization developed to such a high degree the fine art of killing masses of people.

The war twisted all of Europe’s cultural, social, and industrial advancements, destroying, in four monstrous years, an entire epoch, indeed an entire mind-set. The pompous splendor of the Victorian Age, La Belle Époque, and Wilhelmian Germany all vanished, as did Europe’s collective idea of warfare as a glorious and honorable adventure. The Great War yanked us out of the 19th century and hurled us into the 20th. We have never fully recovered from the speed and brutality of that transformation. It is sobering to reflect that more men were killed and wounded at Verdun than the entire U.S. Army lost on both fronts of World War II.

The flesh and blood of two European nations lie side by side as brothers at Verdun, bound together by their suffering, their sacrifice. They share, as Wilfred Owen wrote, an “eternal reciprocity of tears.”

“Verdun transformed men’s souls,” wrote a German soldier. “Whoever floundered through this morass full of the shrieking and dying … had passed the last frontier of life, and henceforth bore deep within him the leaden memory of a place that lies between Life and Death.”

My comments…a shocking but a reminder war can really never really by one party. The world should have learned from the ‘Great War,’ but the killing continues. we will never learn. My prayers dor both sides for those killed and their families…also the wounded, gasses or tormenting for life.

If you ever see a bonafide war hero staring into space while shaving he is not thinking about his deeds of Deering do, most likely he is thinking about the Deering deeds he didn’t do (by his own standards of bravery).

Or, He could be thinking that maybe it was unnecessary to have killed that young enemy soldier.

This notion may explain why so many soldiers are silent about their war experiences.

All other considerations and conclusions as to the effects of Verdun aside, it is difficult to believe that Wilhelm I and Bismarck would ever have tolerated something as wasteful of life and pointless as trench warfare. It is also difficult to believe that politicians are always ready to fight the last war but rarely the next.

Now, at last, you can walk around the areas of battle freely and without incurring arrest. To this day, the trees and bushes are stunted because the soil was, and remains, contaminated by so many chemicals in the shells. There are few birds, frogs or butterflies to be seen or heard, far fewer than at Chernobyl.

For years, the *Zone Rouge* was a prohibited area; if you have the time and money, I urge you to visit it.