By Herb Kugel

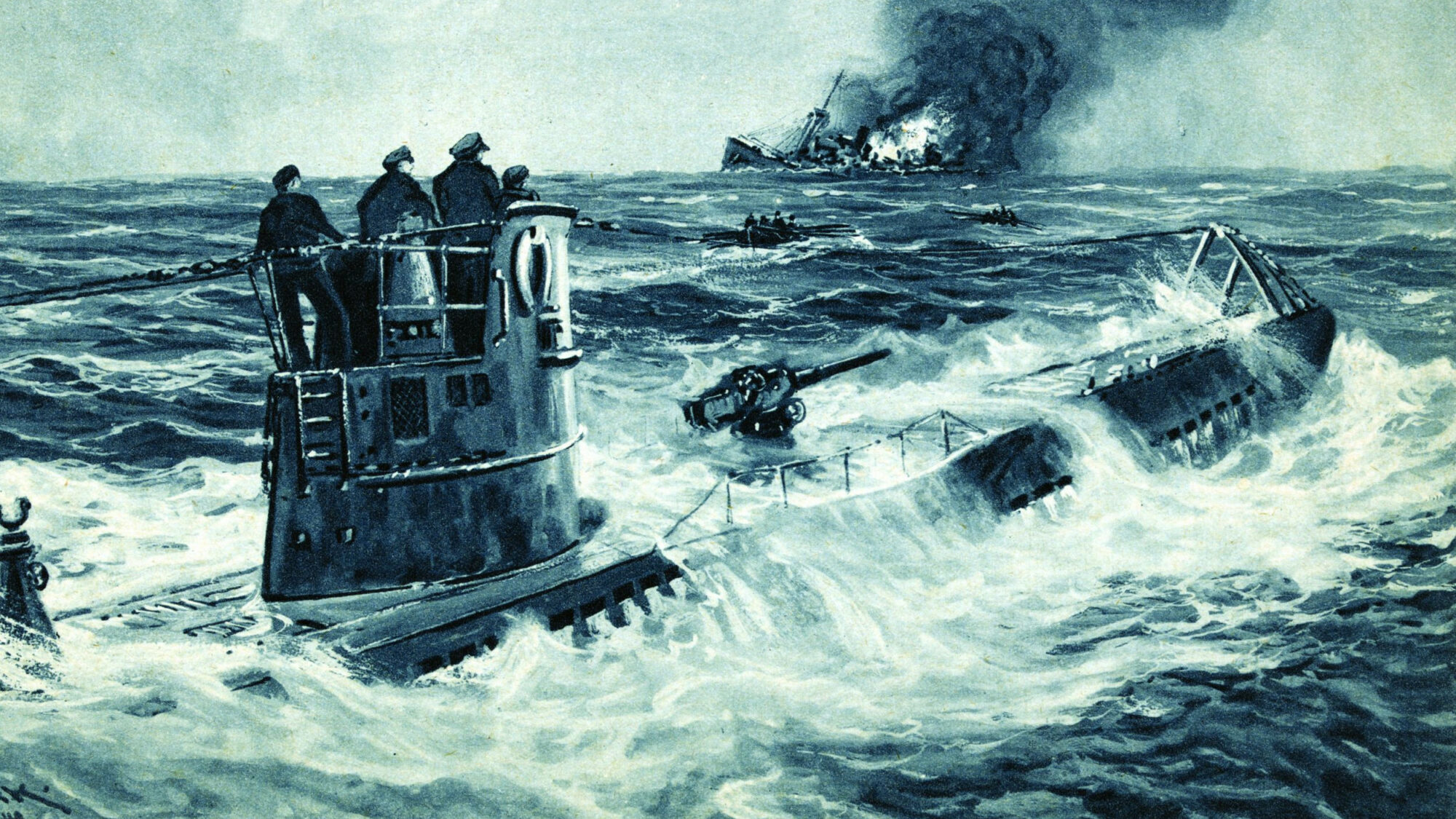

America was not at war, but American sailors were dying when American-owned ships were torpedoed by German submarines. In 1941, few Americans knew of the destroyers USS Niblack, USS Greer, USS Kearny, and USS Reuben James, but these and other American warships were fighting a grim naval war months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

American warships fought this undeclared war in the bitterly cold waters of the North Atlantic. They often struggled through brutal sub-zero temperatures and rapid, violent weather changes. Heavy storms were common; storms developed so quickly that it was often impossible to predict them. In the winter, ice sometimes almost a yard thick covered the convoy ships and threatened to capsize them. Ships sank and sailors died within minutes in the icy water.

On November 5, 1940, Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to an unprecedented third term as president of the United States. This victory gave him the political clout to openly support Great Britain in her struggle against Germany, but by the spring of 1941, the British were in desperate straits both economically and militarily. Under Roosevelt’s order, the United States began using its warships to provide limited escort to merchant ships sailing for Britain, especially ships carrying weapons that America supplied through the Lend-Lease Act, which Roosevelt signed into law on March 11, 1941.

The first skirmish in what became the undeclared naval war between the United States and Germany took place on April 10, 1941, when the destroyer USS Niblack, on patrol in the North Atlantic, intercepted an SOS from the Dutch freighter SS Saleier. The SOS reported the Saleier was torpedoed and sinking rapidly. The freighter’s latitude and longitude placed her 441 nautical miles from Reykjavik, Iceland. The Niblack, ordered to her assistance, sailed all night. The next morning her lookouts spotted three small lifeboats. Before attempting to pick up survivors, the Niblack circled the lifeboats while conducting a sound search for German submarines. The crew of the Saleier, nine officers and 51 men, survived, but at 8:40 am, as the last of them were taken aboard the Niblack, sound contact was made with an “undersea object.”

D.L. Ryan, commander of Destroyer Division 13, with which the Niblack served, described in his report what happened next: “This contact was about two points abaft the starboard beam and if it were a submarine, it was rapidly approaching a position for attack. With safety of ship, crew, and survivors in mind, decision was made to attack instantly … Accordingly … the ship went ahead … at full speed and turned to an intercepting course. When it was estimated the ship should be over the submarine (if one were present) time depth charges were dropped at ten second intervals, and then the ship proceeded to clear the area at 28 knots on course North without further investigation.”

The Niblack arrived at Reykjavik on April 12. The Saleier’s crew was handed over to British authorities. It was later learned that the German submarine, U-52, was not hurt by the depth charges, if indeed the object was the U-52, which later proved extremely unlikely. The Niblack was the first U.S. Navy warship to use its weapons against Germany since World War I.

On May 21, 1941, the unarmed and clearly marked 5,000-ton American freighter Robin Moor, sailing from New York to various African ports, was stopped by the German submarine U-69 about 700 miles off the west coast of Africa. The ship carried a 38-man crew and eight passengers, four men, three women, and one child, all of whom were ordered to abandon the freighter, which was then sunk by the U-69. The Robin Moor was the first American merchant ship sunk by German submarines prior to U.S. entry into World War II. The other American-owned merchant ships sunk had been under Panamanian registry and, thus, flew the Panamanian flag.

A full-scale war between the United States and Germany loomed closer when, on June 14, Roosevelt froze Axis funds in the United States and, on June 16, he ordered German consulates closed and all German diplomats expelled. Branding Germany an “outlaw nation,” he told the U.S. Congress on June 20: “I am … bringing to the attention of the Congress the ruthless sinking … of an American ship, the Robin Moor, in the … Atlantic Ocean…”

Roosevelt climaxed his report with: “We are not yielding and we do not propose to yield.”

The American War Effort Increases

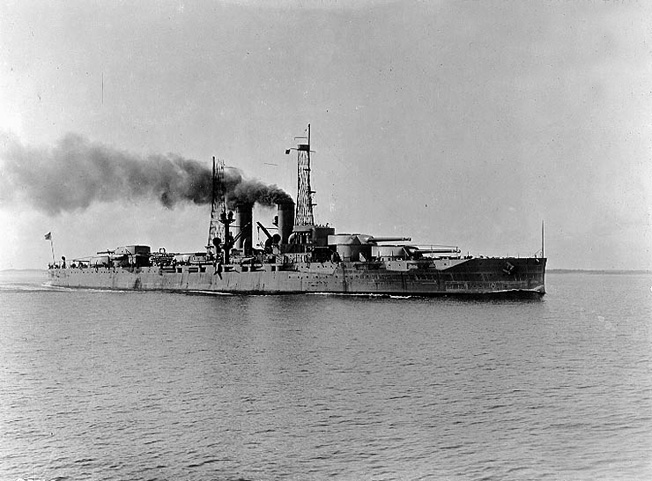

On the same day Roosevelt was reporting on the Robin Moor, the battleship USS Texas, the last coal-fired American battleship, which was launched May 18, 1912, and which served in World War I, was stalked by the German submarine U-203, a state-of-the art Type VIIc submarine almost 29 years younger than the battleship she was chasing. No exchange of hostile fire took place, but the submarine was apparently unable to catch the zigzagging battleship, which was southwest of Iceland.

In June 1941, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill asked Roosevelt to send American troops to Iceland to replace the British garrison there, thus freeing the British soldiers to fight elsewhere. Roosevelt agreed, and on July 1, 1941, the United States and Iceland reached an agreement allowing U.S. Marines to enter Iceland in order to prevent a German invasion. Four thousand Marines were ready for duty in Iceland, which was then a sovereign state under the government of Denmark. It was critical to beleaguered Britain that Iceland not be occupied by Germany. Because of this, Britain had occupied Iceland over a year earlier, on May 10, 1940. Roosevelt’s decision to send Marines to Iceland heightened the risk of war with Germany. The convoy carrying the Marines anchored in Reykjavik harbor on July 7.

The support of the American people for Roosevelt’s action remained steady throughout the year. Historian Richard R. Lingeman points out: “The country was overwhelmingly in favor of aiding England in late 1941. Asked [by a Gallup poll] which was more important: that the United States stay out of the war or that Germany be defeated, sixty-eight percent said it was more important … Germany be defeated.”

While no one died when the Robin Moor sank, this was not true on August 18, when two torpedoes from the submarine U-38 slammed into the Iceland-bound U.S.-Panamanian freighter SS Longtaker. The unescorted and unarmed ship sank within a minute of being torpedoed. Twenty-four of the freighter’s 27-man crew perished.

On September 4, 1941, the destroyer USS Greer was about 175 miles southwest of Iceland when a British patrol plane reported a submarine, later identified as the U-652. The submarine was 10 miles dead ahead. The Greer made sound contact with the U-boat and followed it. The British plane dropped four depth charges, then, for whatever reason, turned away. For more than three hours, the Greer tracked the submarine, repeatedly radioing its position to the British, but there was no British attack. Suddenly, the U-652 changed course and closed on the Greer. Every man on the destroyer was at his battle station when the lookouts sighted an impulse bubble—a big globule of air that was raised when a submarine fired a torpedo. The U-652 had fired without raising her periscope, aiming with her sound equipment.

Within a minute, Greer lookouts sighted the bubbling wake of the first of two torpedoes; it was about 100 yards astern. By then, the destroyer had begun to wheel and was steaming toward the spot where the lookouts observed the impulse bubble. Once the Greer was over the position, the destroyer dropped eight depth charges, but its sound man heard the submarine apparently moving away. Two minutes after the Greer dropped her depth charges, the second torpedo was sighted 500 yards off her starboard bow. It did not strike the Greer. After this, the destroyer lost contact with the submarine but continued searching. She picked up the submarine again that afternoon, closed, then attacked with depth charges, dropping 11. Nevertheless, the U-652 survived. By late afternoon, Greer lost contact with the submarine after a three-hour search, and then continued to Iceland. The USS Greer was the first American warship to be attacked in the undeclared naval war.

The next day, September 5, a German plane bombed and sank the American merchant ship Steel Seafarer in the Red Sea during its voyage from New York through the Suez Canal. A U.S. flag had been prominently painted on the side of the ship.

U-Boats: “Rattlesnakes of the Atlantic”

During Roosevelt’s September 11, 1941, radio speech to the American public, his 18th fireside chat with the nation, he called the attack on the Greer an act of piracy and then continued: “When you see a rattlesnake poised to strike, you do not wait until he has struck before you crush him. These Nazi submarines and raiders are the rattlesnakes of the Atlantic …”

Roosevelt’s bottom line was blunt: “Our … vessels and planes will protect all merchant ships—not only American ships but ships of any flag—engaged in commerce in our defensive waters. They will protect them from submarines; they will protect them from surface raiders.”

The German attacks continued. On September 11, the same day Roosevelt made his fireside chat, a speech that became known as his “Shoot on Sight Speech,” the U.S-Panamanian freighter Montana, carrying lumber from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Reykjavik, was sunk by the German submarine U-105. Eighteen of her 25-man crew died. On September 17, five American destroyers began escorting convoy HX150 from Halifax. This was the first time the United States Navy escorted an eastbound British transatlantic convoy. On September 20, the U.S.-Panamanian freighter Pink Star, carrying general cargo from New York to Liverpool, was sunk by U-552. Thirteen out of the crew of 35 men died. On September 26, the U.S.-Panamanian oil tanker I.C. White was sunk by U-66 while sailing from Curaçao, an island in the southern Caribbean, to Cape Town, South Africa. Three men died in this attack. The tanker was unescorted, unarmed, and fully lit. On October 9, Roosevelt began his efforts to have the U.S. Neutrality Acts changed to allow for the arming of merchant ships.

So far, all the ships that had been torpedoed were merchantmen, but that was about to change. On October 16, 1941, the destroyer USS Kearny was part of an emergency rescue mission. Convoy SC-48, a 52-ship slow convoy moving through bad weather, was under attack by a submarine wolfpack. The convoy defenses were reinforced by five U.S. destroyers, Greer, Kearny, Plunkett, Livermore, and Decatur, but the rescuers made the mistake of bringing their ships too close to those they were trying to protect.

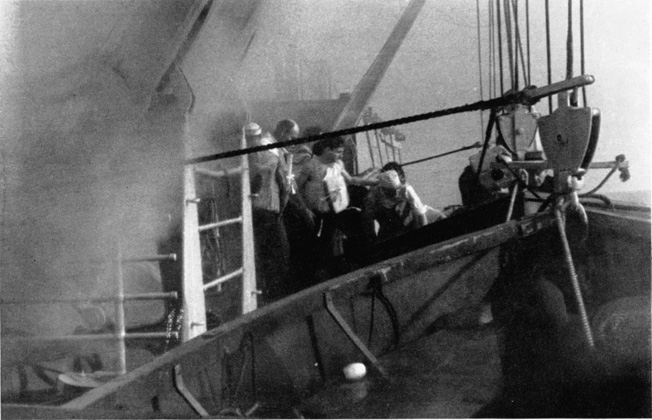

The wolfpack, taking advantage of this error, closed to torpedo range and fired salvo after salvo without interruption. Conditions were made worse for the destroyers when their captains ordered the firing of star shells and flares. The light that was generated dazzled the lookouts and greatly reduced their night vision, which, in turn, made it easier for the U-boats to strike again and again. In the resulting turmoil, the Kearny veered away to avoid colliding with a Canadian corvette and in doing so became a perfect target for the U-568. The submarine fired a spread of torpedoes, one of which struck the Kearny.

Ensign Harry Lyman, a Kearny survivor, later reported: “The U-boat fired three torpedoes at us. One went off the bow, one went off stern and the third hit us on the starboard side at the forward engine room.”

Lyman also reported hearing a terrible roar as the warhead tore through the Kearny’s armor. The resulting explosion killed seven men stationed in the forward boiler room. The force also ripped through the deck, destroying the starboard wing of the bridge. It slammed the forward stack back and cut the siren cord so that the siren could not be shut off. Four other men disappeared, probably blown overboard. In total, 11 men died and 22 were injured. The ship managed to limp to Hvalfjordur, Iceland. She arrived on October 19, escorted by the Greer. A cavernous hole and twisted, misshapen plating disfigured her starboard side below and aft of the bridge. After the repair ship USS Vulcan patched the hole, the Kearny left Iceland on December 24, for Boston and permanent repairs. The Kearny was the first U.S. Navy casualty in the undeclared war in the Atlantic.

“They Can’t Do This to Us”

Two American ships were sunk during the attack on Convoy SC-48. On October 16, the Anglo-American Oil Co. tanker W.C. Teagle was sunk, and on October 17, the U.S.-Panama freighter Bold Venture was lost. The Teagle, carrying 15,000 tons of fuel oil and flying the British flag, was on a voyage from Aruba to Sydney, Nova Scotia, and then on to Swansea; she was torpedoed and sunk by submarine U-558. Though published figures vary slightly, it appears that 41 men on the ship died. Nine survivors were rescued by the British destroyer HMS Broadwater. However, all but one of these men died when the Broadwater was sunk the next day. The Bold Venture, which had left from Baltimore and was sailing for Liverpool with a cargo of cotton, iron, steel, copper, and wood, also suffered casualties.

On October 19, the U.S. freighter SS Lehigh was sunk. The Lehigh, sailing from Bilbao, Spain, to Africa was torpedoed by the U-126. The 4,983-ton freighter was unarmed, unescorted, and clearly marked as American. No one died in this attack. Sam Hakam, the radio operator on the SS Lehigh described what happened. “The torpedo struck without warning. There was a loud explosion followed by a towering plume of smoke and debris. My first reaction was, ‘This is just like you see it in the movies.’ … Utter astonishment and disbelief followed. Jimmy, the fireman on the 4 to 8 watch, stood on deck shouting, ‘They can’t do this to us,’ over and over … He had reason to shout. It was October 19, 1941. We were not in the war yet.”

Although there had been no declaration of war, the United States was at war. The oiler SS Salinas, sailing about 700 miles east of Greenland, was torpedoed on October 30. There were no casualties, and the damaged ship managed to make it safely to port.

“The Sinking of the Reuben James“

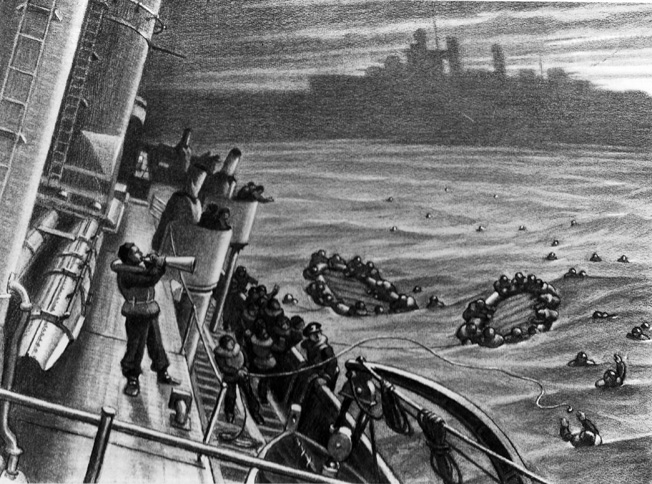

On October 23, 1941, the USS Reuben James sailed from Argentia, Newfoundland, with four other destroyers of the U.S. Escort Group 4.1.3. Its task was to escort convoy HX156. The Reuben James had been positioned directly between an ammunition ship in the convoy and the known position of a German U-boat wolfpack. At 8:34 am, she was hit by a torpedo from submarine U-552.

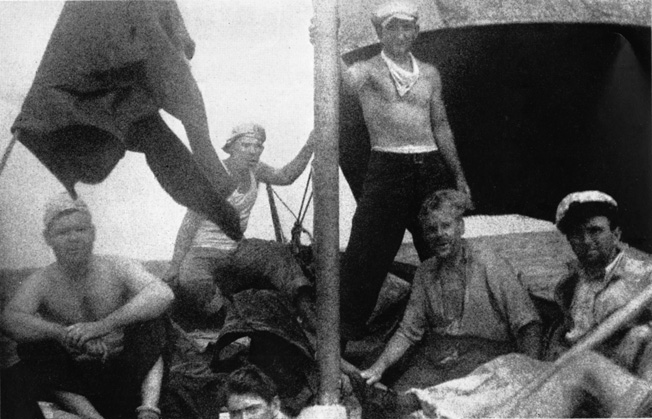

The torpedo ignited the ammunition in the forward magazine. The resulting explosion tore the ship in two. The forward section sank immediately, taking all hands there into the icy water. As the stern sank, the ship’s depth charges exploded and killed survivors in the water. At that moment, Chief Machinist’s Mate William H. Bergstresser became the doomed ship’s commander. He was the only survivor among the Reuben James’s 20 officers and chief petty officers. The destroyer carried a crew of 144, of which only 44 survived. Aside from the friends and relatives of the dead sailors, few Americans appeared to be deeply moved.

Political activist and balladeer Woody Guthrie composed “The Sinking of the Reuben James,” a stirring and patriotic song, commemorating the tragedy. The Nazis had invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, just over four months before the Reuben James went down. An ardent leftist, Guthrie had been composing and singing antiwar ballads for some time. Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union reversed all that. Great Britain and Soviet Russia were abruptly uncomfortable allies against Nazi Germany. Guthrie and other leftists made what conservatives and anticommunists ridiculed as “the great flip flop.”

The peace songs quickly vanished. Guthrie immediately composed a series of patriotic win-the-war ballads that were recorded and released soon after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Probably the most famous of these was “The Sinking of the Reuben James.” Whatever the reason for its writing, the song was certainly a patriotic call to arms:

“Have you heard of the ship called the good Reuben James?

Manned by hard fighting men both of honor and fame

She flew the Stars and Stripes of the land of the free

But tonight she’s in her grave at the bottom of the sea.”

Chorus:

“Tell me what were their names,

tell me what were their names?

Did you have a friend on the good Reuben James?”

The Undeclared War Ends, the Official War Begins

The United States continued moving closer to war with Germany. A November 5, 1941, Gallup poll indicated that 81 percent of the American public favored arming merchant ships and 61 percent favored allowing these ships to enter war zones. On November 6, the German blockade runner Odenwald, carrying a cargo of rubber from Japan, was captured in the Atlantic near the equator. She was taken by the cruiser USS Omaha and the destroyer USS Somers.

While Roosevelt was successful in pushing through changes to the Neutrality Acts, the U.S. Congress remained hesitant. The new rules specified that merchant ships could be armed and that U.S. ships could enter both combat zones and belligerent ports. The Senate approved the revision on November 7, and the House of Representatives reluctantly agreed on November 13. Senate approval was 50-37, and House approval was 212-194. Nevertheless, on November 11, 1941, the submarine U-561 sank the 5,592-ton Panamanian freighter Meridian, and then the 2,939-ton Panamanian freighter Crusader on November 14. Both ships were part of convoy SC-53.

On December 2, 1941, the German submarine U-43 fired a torpedo at the unarmed and unescorted oil tanker SS Astral, which was traveling from Aruba to Lisbon, Portugal. The tanker was clearly marked as American; flags were painted on its sides. The torpedo missed, and the tanker began zigzagging in a desperate effort to survive. It was to no avail. The U-43 hunted her through the night and at 9:24 the next morning sent two torpedoes into her, one astern and one amidships. The tanker, carrying a crew of 37 men and 78,200 barrels of gasoline and kerosene, exploded and sank within minutes. There were no survivors. Gasoline and kerosene burned for an hour on the water after the ship went down. That same day the U.S. merchant ship SS Dunboyne received the first Naval Armed Guard crew.

The last American merchant ship sunk in the undeclared war was the unarmed SS Sagadahoc, which was stopped in the South Atlantic on December 3 by the submarine U-124. The German commander, deciding the ship carried contraband, ordered its 35-man crew into lifeboats. The Sagadahoc was then sunk. However, one sailor failed to leave the ship and went down with her. He was probably the last sailor to die in the unofficial war in the Atlantic.

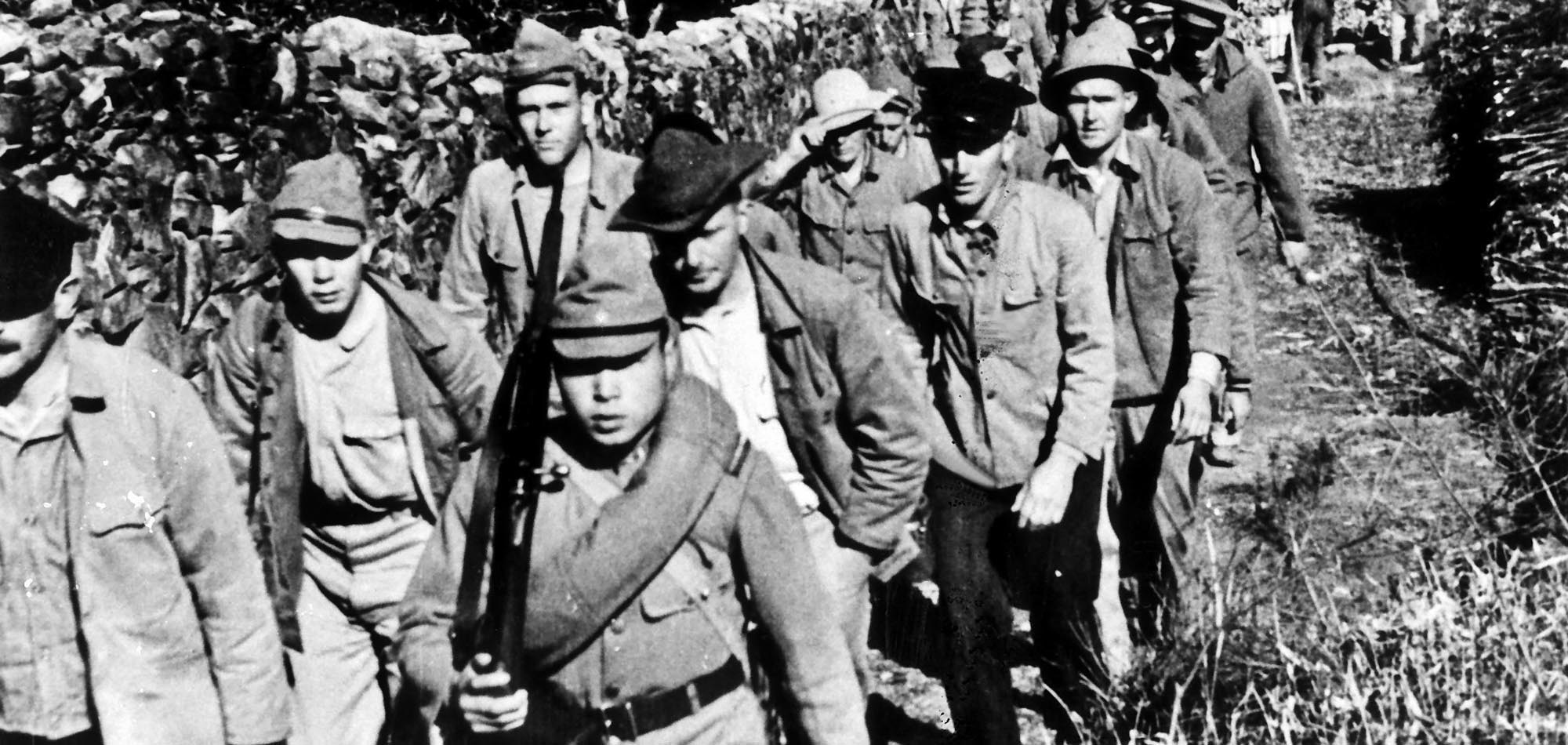

The undeclared naval war between the United States and Germany was coming to an end. Four days after the Sagadahoc was sunk, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. On December 11, 1941, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments