By Eric Niderost

On May 6, 1939, King George VI of Great Britain and his wife Queen Elizabeth arrived in Portsmouth to board the liner Empress of Australia, which was to take them to Canada and subsequently to the United States. This was going to be the first time a reigning British monarch ever officially visited North America, which was exciting to the crowds that had gathered to watch the royal departure. The fact that Britain was on the brink of war with Germany gave the occasion a certain poignancy.

The king hoped for the best, perhaps an 11th-hour development would avert the looming conflict but privately he expected the worst. He wrote uneasily, “I hate leaving the country with the situation as it is.” Yet the king was a man of principle to whom personal desires were subordinate to duty. The war, if it came, promised to be a severe trial. Britain needed the help and support of the Dominion of Canada, and, if lucky, additional aid from the United States.

A Hazardous Voyage

The trip was also a way to salvage the reputation of the monarchy, tarnished by the abdication of George’s older brother, Edward VIII, in 1936. Edward had triggered a crisis when he wanted to marry a twice-divorced American socialite, Wallis Simpson. Declaring he could not bear the burdens of kingship without the “help and support of the woman I love,” he stepped down in December 1936.

Edward married Mrs. Simpson and was created the Duke of Windsor, but controversy dogged him. The duke and duchess made an ill-advised excursion to Nazi Germany, a propaganda coup for Adolf Hitler. So, there was a lot riding on the new king’s trip to America.

Queen Mary, George’s mother, was also on hand at the departure, accompanied by her grandchildren, Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret. The old queen was the very personification of Britain’s glorious Victorian past. Regal in bearing and ramrod straight, she waved a handkerchief at her departing relations. Margaret, only eight years old, started to cry, but 13-year-old Elizabeth took charge. “Wave,” she admonished her sister, “don’t cry!”

Originally, the Royal Navy battlecruiser HMS Repulse was supposed to have carried the king and queen over the ocean, but given the uncertainty of the times, it was ultimately decided that the ship had better stick to home waters. The Empress of Australia was an ironic replacement, since it was an old German-built ship that had been given to Britain as a reparations payment after World War I.

The voyage started out well but soon ran into trouble. The ice pack was large that year and had drifted farther south than ususal, into the North Atlantic. To avoid the icebergs the captain was forced to likewise sail farther south than usual. A thick, clammy fog also made the voyage potentially hazardous. Queen Elizabeth wrote Queen Mary, “The fog was like a white cloud round the ship, and the fog horn blew incessantly.… Incredibly eerie, and really quite alarming. We very nearly hit a berg the day before yesterday.” The fact that there was a survivor of the ill-fated Titanic aboard did nothing to lighten the mood.

While the king and queen were at sea the Duke of Windsor once again displayed his penchant for troublemaking. Edward made a radio broadcast to America, his text a seeming endorsement of appeasement. The broadcast was made from Verdun, France, site of one of the bloodiest battles of World War I, and a not too subtle reference to the horrors of war. Let Hitler have his way, the duke’s message seemed to say, or else face the consequences of another global conflagration. On one or two occasions Edward even gave the Nazi salute to appreciative German onlookers.

The voyage was supposed to last seven days, but fog and ice caused an additional two-day delay. Their majesties landed at Wolfe’s Cove, Quebec, on May 17, 1939. It was the beginning of a month-long, 10,000-mile odyssey that would be both exhilarating and exhausting for the royal pair.

Roosevelt’s Gambit

The trip was the brainchild of Canadian Prime Minister William Mackenzie King, who would play host to the royal couple and also accompany them to the United States as minister in residence. The American leg of the journey was largely added at the personal invitation of President Franklin Roosevelt. The Americans had wanted the monarchs to visit the United States in May, almost as soon as they disembarked, because the weather would not be as hot as in June. Mackenzie King, perhaps not wanting to be upstaged by the charismatic Roosevelt, or make it seem as if the United States was more important than the Dominion of Canada, refused.

As a result, King George and Queen Elizabeth would tour most of Canada for three weeks, reserving only about five days for an American excursion. Roosevelt, ebullient as ever, agreed. According to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the president “invited them to come to Washington largely because, believing that we all might be engaged in a life and death struggle, in which Great Britain would be our first line of defense, he hoped their visit would create a bond of friendship between the two countries.”

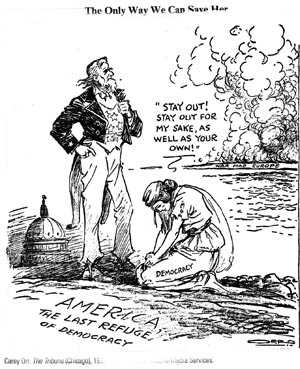

True enough, but there were other reasons why the president pushed for a royal visit. The King of England would be a pawn in the game of political and diplomatic chess that Roosevelt was playing against isolationists at home and, more indirectly, against Hitler and others of his ilk. King George was considered colorless, but Queen Elizabeth was noted for her immense charm. Their visit would not only make a statement about Anglo-American solidarity in the face of fascist aggression, but also soften the isolationist attitudes that currently prevailed.

The Seams of American Isolationism

Isolationism ran deep in 1930s America, fueled by geography, the Great Depression, memories of World War I, and the fierce independence inherent in the American character. Roosevelt did not want to go to war, but he was also one of the first American leaders who recognized the threat that Hitler represented. Roosevelt the politician had to trump Roosevelt the statesman, at least for the time being. He had to proceed cautiously, or he might find himself out of office.

Geography played a major part in the isolationist attitudes. Before the age of satellite communication, jet travel, and the Internet, the world was a much larger place. To a wheat farmer in Kansas or an auto worker in Detroit, the mighty Atlantic and vast Pacific were oceanic “moats” that protected the Americas from the violence and machinations of the rest of the world.

The airline industry was, if not in its infancy, still struggling with adolescence. Most people traveled by train, in part because many still feared flying, but mostly because air fares were beyond the reach of the average person. In 1935, Pan American Airways inaugurated its fabled “China Clipper” service from San Francisco to Manila. In this service, flying boats island-hopped to Asia, taking about 60 hours one way to do so. Fares were $375 one way (around $4,000 in today’s money) or $675 round trip (about $7,000 to $8,000 today).

Most foreign travel was by ship. The British liner Queen Mary made a record crossing to New York in three days, 21 hours, and 48 minutes, but most vessels took about five days. Asia was even more distant, with most ships taking about 15 days to sail from San Francisco to Japan. Overseas travel was, in the main, for the wealthy. When average Americans viewed foreign newsreels, they might as well have been looking at pictures of the moon.

There was also a feeling that somehow America had been duped by the Allies into entering World War I. The United States had suffered over 300,000 dead and wounded, and yet the cause of world peace, so idealistically promoted by President Woodrow Wilson, was not advanced by the sacrifice. If anything, by the 1930s the world was much worse off. And as if to add insult to injury, the United States had loaned Europe billions of dollars after the war to help get it on its feet. Most of the collective debt was still unpaid.

Some isolationists even blamed the Great Depression, at least in part, on America’s entry into World War I. They argued that American war profiteers had created an illusion of wealth in the 1920s, a bubble that finally burst in 1929. Disillusionment with the war turned most Americans inward. Europe was seen as irredeemably corrupt.

Isolationists applauded when America did not enter the League of Nations, precursor to today’s United Nations. Politicians like Senator William E. Borah of Idaho, Gerald P. Nye of North Dakota, and Burton K. Wheeler of Montana become more and more rigid in their attitudes, not recognizing that the world was indeed changing, and that the Pacific and Atlantic moats were not going to be as effective as they were in the 19th century.

Congressional Neutrality Acts

President Roosevelt felt all these trends keenly. In the first years of his presidency, he was occupied with the economic woes at home, but after 1935 foreign affairs came to the fore, beginning with Italian leader Benito Mussolini’s brutal conquest of Ethiopia. In response to the growing tensions in the world, Congress passed a series of Neutrality Acts, the last one issued in 1937. Among other things, if a war broke out anywhere in the globe, American ships would be prohibited from carrying arms to belligerents, and no loans, directly or indirectly, could be extended to warring parties. Even nonmilitary goods could be excluded, unless prepaid.

In late 1937, Congressman Louis Leon Ludlow introduced proposed legislation that would add an amendment to the Constitution. The amendment, if adopted, would make any congressional declaration of war illegal, unless the United States was physically invaded. If there was no armed invasion, Congress could only declare war if the action was confirmed by a nationwide vote, a national referendum. Luckily, enough congressmen realized how ludicrous the measure was and turned it down, but it showed the depth of isolationism in the country.

The Woeful State of America’s Military

Roosevelt’s main concern in the late 1930s was to outmaneuver the isolationists and bolster America’s woefully neglected defenses. The president was not about to enter any war if he could help it, but given German and Japanese aggression, he realized the need to strengthen the U.S. armed forces.

Congress’s “penny wise, pound foolish” neglect of the Army and Navy was yet another byproduct of the prevailing isolationism. In 1939, the U.S. Army was described by Life magazine as the “smallest and worst equipped” army of the great powers. Most of its artillery was World War I-vintage, and it was short of machine guns, howitzers, and personnel. The Army’s strength was listed as 174,000, ranking it 19th in the world, sandwiched between Portugal and Bulgaria. But even this figure is misleading; if one counts the proportion of men under arms to the total population, about 130 million, the U.S. ranking was more like 45th.

The Republic seemed formidable, but the Army and Navy “arm” that wielded the Republic’s sword was atrophied, weakened by draconian budget cuts and purposeful neglect. Roosevelt wanted to strengthen the armed forces, and help victims of Japanese and fascist aggression, but politics tied his hands. His only weapons were the written and spoken word, but rhetoric would not stop Hitler’s tanks.

A Hotdog Picnic

Hitler’s bullying had caused Britain and France to appease him in the infamous Munich Pact in late 1938. Abandoning even the pretense of moderation, Hitler marched into Bohemia and Moravia, in effect destroying the rump of what was left of the Czech Republic.

Roosevelt made his first overtures regarding a royal visit to America at the height of the Munich crisis. The president was often accused of being devious, even mendacious at times, but in this case the political climate demanded he proceed with the utmost caution. Eschewing the normal diplomatic channels, he wrote a personal letter to the king, inviting him to America, saying “it would be an excellent thing for Anglo-American relations.”

Of course there were details to sort out, which required time. Roosevelt asked that all negotiations regarding the royal visit be kept secret, at least until plans were finalized and more definite. Hard-core isolationists like Senator Borah were always on the lookout for “foreign entanglements” and might consider the king’s trip to be the beginning of an unwanted Anglo-American alliance. To assure secrecy, Roosevelt had Joseph P. Kennedy, U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain, hand deliver the letter personally to the king. Kennedy complied, but later grew resentful when Roosevelt neglected to advise him of the negotiations and their progress. The president tried to mollify Kennedy, but the ambassador still felt his prestige was somehow compromised.

After the king and queen’s visit was made public, a predictable variety of reactions ensued. Eleanor Roosevelt was determined to have the royals experience something that they could not get elsewhere, namely an authentic slice of real American culture. This put her in conflict with her domineering mother-in-law, Sara Delano Roosevelt. Since Springwood, the Roosevelt family estate at Hyde Park, New York, was going to be on the itinerary, the First Lady decided to stage a picnic for the royal couple. Sara Roosevelt, the imperious matriarch of the family, was aghast. The old lady was Victorian to the core, and something of a social snob to boot. The idea of serving “common” picnic foods like hot dogs was unthinkable. But in this battle of wills, Eleanor got her way.

Actually, the elder Mrs. Roosevelt was not alone in her opinion. “Oh dear, oh dear,” Eleanor wrote with tongue in cheek. “So many people are worried that the dignity of our country will be imperiled by inviting royalty to a hot dog picnic!” One or two hot dog companies then competed for the honor of having their brand consumed by the king and queen. In the end, none of the competing brands got the coveted prize. Harry Johannson, 25-year-old son of Springwood’s cook, Nellie Johannson, was the one who obtained the royal frankfurters. The young man traveled to Poughkeepsie, New York, and went directly to Swift and Company. He picked Swift because, quite simply, they were “the best.”

Once the royal visit was announced, the isolationists in Congress accepted it as a fait accompli. They could not resist continuing their partisan sniping, however. Senator Borah, intransigent as ever, suggested that if there was a lull in the conversation the president might ask the king about paying the $5 billion of war debt that Britain owed the United States.

A Spartan Reception

The king and queen’s sleek streamliner entered the United States via the suspension bridge that spanned the border at Niagara Falls. The royal train, its cars a dazzling blue and silver, stopped at the small brick station where dignitaries waited to extend an official welcome to their Britannic majesties. Floodlights bathed the platform, but there was no bunting, and only a small patch of red carpet. The only real sign that something unusual was going on was the presence of two small British and American flags and the unmistakable odor of fresh paint.

Secretary of State Cordell Hull and his wife were on hand to greet the royal pair, as was Sir Ronald Lindsay, the British ambassador. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth appeared on the observation car, but after a few hasty words of greeting, Hull and his party boarded the same train. The idea was to continue the trip overnight, riding through Buffalo and on to Washington, D.C. The Niagara Falls ceremony was spartan because it had to be. Neither the city of Niagara Falls nor the New York Central Railroad had enough money for elaborate decorations. One British correspondent, not knowing the financial realities, was impressed by American “simplicity.”

As the train sped southward, Hull and the king had some private political conversations in the observation car before finally turning in for the night. Progress was swift, because the way was cleared and all signals flashed green. Every culvert railroad crossing and bridge had been thoroughly check by the Secret Service because there was a fear that radical Irish Republican Army terrorists might have planted a bomb in an attempt to assassinate the king.

Even the FBI or Secret Service could not inspect every mile of track, so a “pilot” train went ahead as a decoy and locomotive “guinea pig.” If there were any explosives on the track, the pilot train would blow up first. The pilot train was filled with reporters, who no doubt were not enthusiastic about these arrangements! And, as if to add to their woes, their locomotive developed engine trouble and was force to a siding in Pennsylvania. The royal train flew past, so the reporters came into Washington too late to cover the arrival.

“God Save the King”

President Roosevelt and a host of dignitaries met the royal couple at Washington’s Union Station. It was the first time a president had greeted his guests outside the White House. Eleanor Roosevelt was all smiles, but she later admitted she dreaded such formal occasions. After the train pulled in the king and queen appeared, His Majesty wearing the full dress uniform of an admiral of the Royal Navy.

Roosevelt was also in formal attire, standing with the help of an aide. Leg braces weighing some 40 pounds were hidden beneath his pants legs. Secretary Hull formally introduced the two heads of state. “Mr. President,” Hull intoned with his soft Tennessee drawl, “I have the honor to present their Britannic Majesties.” Extending his hand, a beaming Roosevelt said “At last I greet you!” The king warmly shook the president’s hand and replied, “It is indeed a pleasure for Her Majesty and myself to be here.”

The Marine Band struck up “God Save the King,” then followed with the obligatory “Star Spangled Banner.” This concluded the formal greetings, so the president and Mrs. Roosevelt escorted their guests to waiting limousines past a guard of honor. A motorcade formed up to take the king and queen to a reception at the White House.

The motorcade left the station and proceeded up Constitution Avenue as a nearby battery of artillery boomed out a 21-gun salute to honor the royal pair. An estimated 600,000 people lined the parade route, cheering lustily as the limos slowly drove by. The weather was unbearably hot, hovering somewhere around 94 degrees. The king must have been suffocating under his heavy uniform that was festooned with medals and dripping with gold braid, but he put on a brave face. Even Roosevelt looked par-boiled in his cutaway coat and striped trousers.

Soldiers, sailors, and police were stationed every few feet along Constitution and Pennsylvania Avenues, partly for show and partly as crowd control for the enthusiastic, surging masses. Queen Elizabeth was the star of the show and would continue to dazzle throughout their American sojourn. She seemed radiant in spite of the heat, with brilliant blue eyes and a manner that oozed genuine grace and charm.

People who were watching from the tall buildings that lined the route were disappointed, because Her Majesty held a parasol to guard her delicate features from the sun’s blistering rays. At one point, when Eleanor Roosevelt waved to the crowd, a spectator impertinently yelled, “Put your hand down! Let’s see the queen!”

Arriving at the White House

The motorcade finally reached the White House, driving into the south entrance. There the king and queen were greeted by members of the diplomatic corps. There were some sticky moments that had nothing to do with the heat. Because of the rule of precedence, the Ambassador of Japan and the Ambassador of China stood next to each other, though the two nations were in the midst of a bloody war. The reception was short because of a scheduled garden party at the British Embassy.

That party was considered the event of the season, and invitations were much sought after by Washington’s political and social elite. The temperatures were still high, and a smothering humidity added to the discomfort. The oven-like atmosphere produced some bizarre concessions to the weather. One senator wore a straw hat, while Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan wore an ice cream suit.

Vice President John “Cactus Jack” Garner was an embarrassment to all concerned. The garrulous old Texan was famed for his description of the vice presidency as “not worth a bucket of warm piss,” though reporters had sanitized the quote to “warm spit.” Gardner lived up to his reputation by going up to King George and jocularly slapping him on the back.

Roosevelt returned the hospitality with a formal state dinner during which he toasted his royal guests, saying the United States “welcomes on its soil the king and queen of Great Britain, of our neighbor Canada, and of all the far-flung British Commonwealth of Nations.” For all of Roosevelt’s bonhomie, he felt the British Empire was an antiquated institution and could not bear to mention it specifically.

After the formal dinner, guests were entertained by a varied lot of artists. Kate Smith belted out her rendition of “When the Moon Comes Over the Mountain,” but the rest of the program was decidedly rural in nature. North Carolina’s Soco Gap Dancers did a rousing square dance, and the Coon Creek Girls from Pinchem-Tight Hollow, Kentucky, fiddled away the night, literally and figuratively, with country tunes. African American opera singer Marian Anderson was the highlight of the evening. Anderson sang “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord,” “Tramping,” and “Ave Maria” in a beautiful contralto. The affair broke up about midnight, and everyone considered the visit to be a success so far.

“The British are coming!”

Friday, June 9, 1939, was the second full day in Washington, with a schedule that included 10 engagements in 11 hours. But the king and queen considered a visit to Capitol Hill the most nerve-wracking of all. Virtually all of Congress would be on hand to meet them. The majority of Congress were rabid isolationists.

The timing of their visit was superb, or horrendous, depending on one’s political views. The Bloom Bill had recently come out of committee, a proposal what would, among other things, alter neutrality legislation by lifting the arms embargo and allowing the “cash and carry” concept to go forward. That is, belligerents would be able to buy war materials from the United States for cash, not credit, and would be required to ship the purchases overseas themselves.

Earlier, Roosevelt tried to set a fire under Congress in support of the bill, confiding to Senator Tom Connally of Texas that he would “like to have the arms embargo lifted before their [the monarchs’] arrival.” But the stubborn solons would not move so fast. In fact, one congressman snidely called the bill “a present to King George.” When King George and Queen Elizabeth arrived at the Capitol the bill was set to be voted on the very next week. Its fate hung in the balance.

Congressmen assembled under the capitol’s vast and soaring dome, waiting for the royal arrival, and the air was abuzz with anticipation. Vice President Garner started telling “down home” stories and ribald jokes, evoking titters and then gales of laughter from those standing immediately beside him. Some of the more conservative senators gave him icy stares, but Garner was undeterred. He walked over to the door and peered out over the Capitol steps. Suddenly, he looked back to his colleagues and loudly proclaimed, “The British are coming!”

The “British” were indeed coming. King George and Queen Elizabeth’s motorcade had arrived, and within minutes they were standing in the rotunda ready to meet members of Congress. By accident or design, the royals were standing under a great canvas paining of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown in 1781, the culminating battle of the American Revolution that gave independence to the United States.

The king and queen’s regal bearing, obvious charm, and genuine affection for the United States won many hearts, and perhaps even a few minds. Senator Borah, the arch isolationist, was wearing a formal morning suit he had not donned in 35 years. The king, usually deemed colorless and dull, surprised many when he called Ellison D. Smith of South Carolina by his nickname, “Cotton Ed.” Louisiana Congressman Robert Mouton kissed the queen’s hand. Elizabeth soon had everyone under her spell. Congressman Ned Patton remarked, “If America can keep Queen Elizabeth, Congress will regard Britain’s war debt as cancelled.”

The Trip to New York

The visit to the halls of Congress was a success, but there were many more stops on the royal agenda. There was a cruise down the Potomac to visit George Washington’s estate and place a wreath at his tomb, a stop at a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, and a brief stay at Arlington National Cemetery to pay respects.

King George and Queen Elizabeth next departed Washington for a brief glimpse of New York and the World’s Fair that was being heavily promoted at the time. Their Majesties were greeted by New York Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia and New York Governor Herbert H. Lehman, then were whisked off to the World’s Fair grounds at Flushing Meadow. New York had not seen an affair like this since Lindbergh’s flight in 1927; some three and a half million people turned out to see the king and queen

The World’s Fair of 1939 was justly famous, but as the tour progressed the king seemed more and more agitated, even impatient. Finally, nature won over royal dignity. “Where is it?” the king asked with a note of real urgency in his voice. Fair promoter Grover Whalen finally got the hint, and the king was led to the men’s restroom.

After New York it was on to the last stop on the royal tour, a brief stay at the Roosevelt country home at Hyde Park. The president and First Lady had gone ahead, so they were sitting in the mansion’s library ready to receive their royal guests when they arrived. Sara Delano Roosevelt insisted that the king would want tea to drink, not a cocktail. For once ignoring his mother’s imperious demands, Franklin had the cocktail shaker primed and ready when the king and queen appeared.

“My mother thinks you should have a cup of tea—she doesn’t approve of cocktails,” the president confided.King George eagerly accepted a cocktail, adding, “Neither does my mother!”

That evening the president, King George, and Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King discussed political issues after the rest had turned in for the night. Superficially, the king and the president were a study in contrasts. Roosevelt was older, loved the limelight, and was almost always charming. The king was painfully shy, hated the limelight, and disliked being king.

Yet the pair also had things in common. Stricken with polio that made him a paraplegic, Roosevelt had overcome his disability, psychologically if not physically. King George had a terrible stutter, which made public speaking agony, though he managed to partly overcome the disability in time. Both men also were basically country squires at heart, but with a social conscience and a hatred of fascism.

In 1939, Roosevelt was mainly interested in the defense of the Western Hemisphere, not in entering a European war. He told the king that if war came he would try and relieve pressure on the Royal Navy by guarding the approaches to the Americas himself. The president also hoped that, again if war broke out, the United States could acquire bases on British colonial soil, places like Bermuda and points around the Caribbean.

Roosevelt also confided that he hoped he could alter those isolationist neutrality laws and try to change American public opinion. The president was sincere in wanting to help Britain, as his later actions proved, but he also was guilty of some exaggerations. If London was bombed, Roosevelt assured King George, the United States would come in. Perhaps President Roosevelt felt he had to stretch the truth a little to reassure a potential ally that was on the brink of armed conflict. The three men talked until about 1:30 am, when Roosevelt, noting the hour, patted the king on the knee and said, “Young man, it’s time for you to go to bed.”

“Good Luck to You! All the Luck in the World!”

The next day, Sunday, June 11, was devoted to divine services and the celebrated picnic lunch. After church, the royals were conveyed to Top Cottage, a cozy dwelling about four miles from the main mansion. There was a wide variety of food on the menu, including steak, smoked ham, and local Duchess County strawberries. But it was the hot dogs that received the lion’s share of attention.

“What are these delicacies?” the king politely inquired. Once the concept was explained to him, he wolfed them down with gusto. He ate two but grew a little less enthusiastic when he spilled some mustard on his spotless suit. Later, the king seemed to favor the memory of smoked turkey, another American food that was new to him.

The king and queen departed from Hyde Park that evening. The president and Mrs. Roosevelt were at the train station to see them off. Once they boarded, the president called out, “Good luck to you! All the luck in the world!” As the train pulled out of the station, crowds who had assembled to see the royal visitors spontaneously started singing “Auld Lang Syne.” It was poignant because no one knew what fate awaited them as war clouds thickened over Europe.

The visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth reassured the British that America was, in spite of the strong strain of isolationism, a country that was a friend and possible future ally in the struggle against Hitler and fascist aggression. The royal visit was generally popular and played its part in the eventual weakening of isolationism in the United States.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments