By Gregory Peduto

The men of the expeditionary force beat a hasty retreat through the seven-foot-tall African grasses. Poison-tipped arrows let loose by pursuing Bunyoro warriors rained down upon them in deadly torrents. The men could barely keep their composure as the Bunyoro launched an ambush that threatened to swallow up the fleeing column. The panicked soldiers’ only solace was that their commander, professional hunter, explorer, and writer Samuel White Baker, was a man of indomi-table will and iron determination.

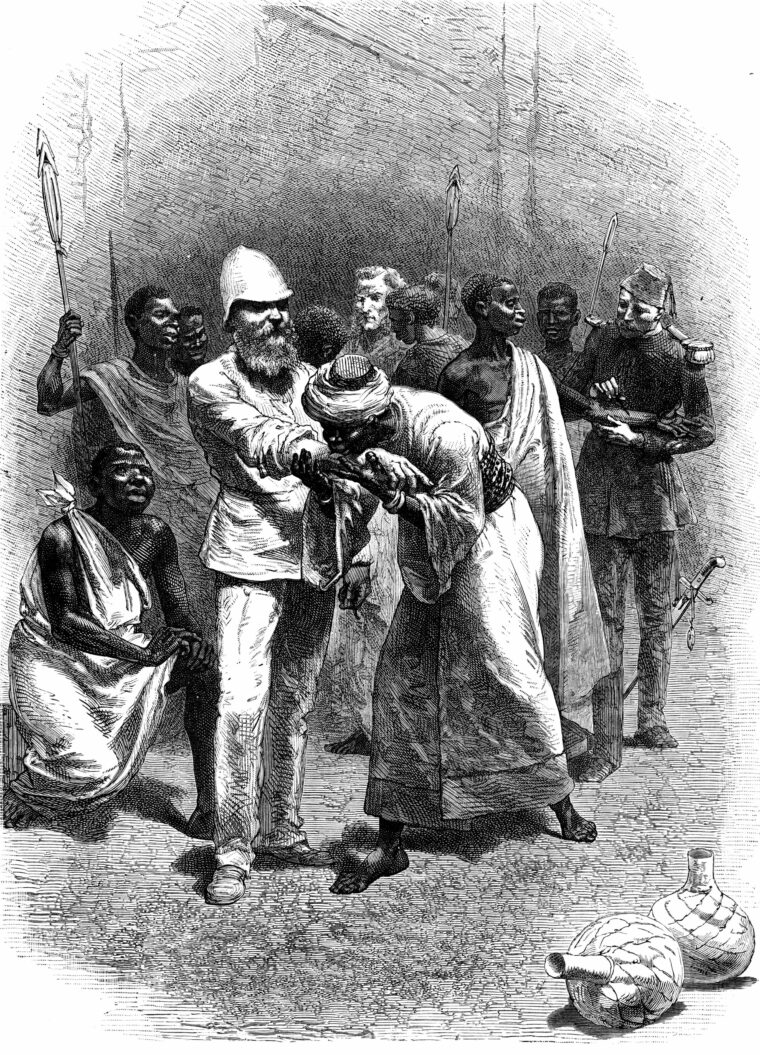

Baker had led the party into the heart of the Sudan to eradicate the slave trade at the behest of Khedive Ismail of Egypt. Baker always led from the front and seldom missed a shot, and this engagement was no exception. He almost single-handedly kept the fierce tribesmen at bay with his muzzle-loading elephant gun, affectionately known as “Baby,” which he wielded like a enormous shotgun stuffed with over 40 pellets. He also occasionally fired off explosive rounds that left “very little of a man if they hit him.”

The Upbringing of an Adventurer

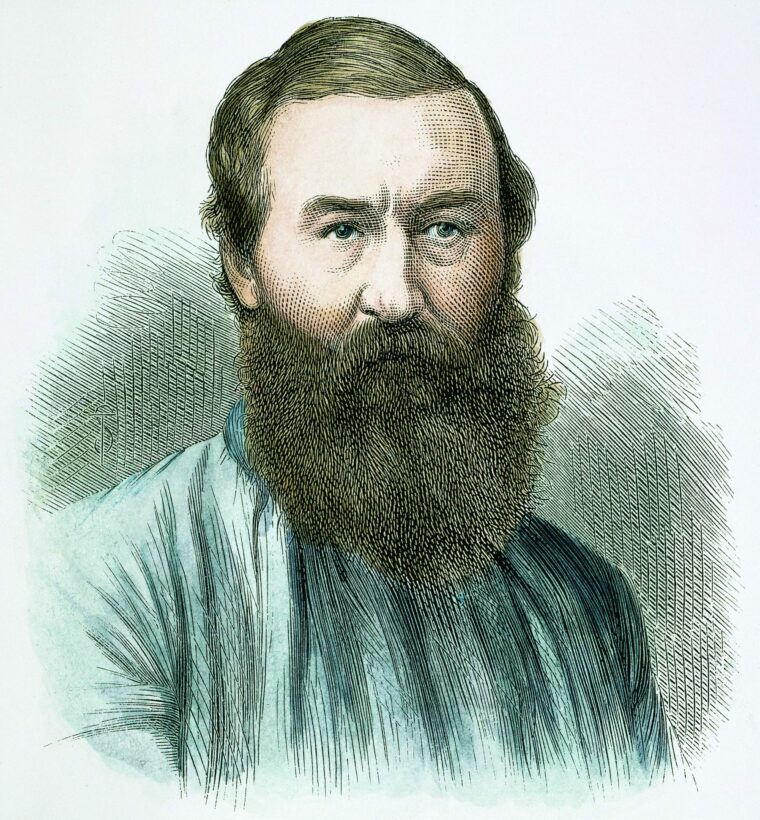

Baker’s whole life had led to this moment. Born in London in 1821, he was an atypical Londoner. Enthralled with the natural world, the tyke’s pockets were constantly crammed with all manner of odorous flora and slithering fauna. His teachers considered him as a “plucky little fellow” with an extremely inquisitive mind that often landed him in trouble. One incident occurred on Samuel’s first exposure to his earliest love, gunpowder. The boy’s ill-fated experiment resulted in a roaring explosion that blew out every window in his grandfather’s house.

When Baker was 12, the family relocated to southwestern England, a place more appropriate for a boy obsessed with stalking, shooting, and explosives. The local children quickly found that the pint-sized youth could scrap with the best of them, and Baker bloodied many insulting lips and offending noses. During his schooling at Gloucester College, the boy developed a reputation as an excellent pugilist, freelance bully slayer, and ballistics prodigy who routinely tried to convince veteran redcoat officers of the superiority of rifled arms to their beloved Brown Bess muskets.

Baker’s obsession with rifled arms led him to master gunsmith George Gibbs, who constructed a special rifle of the teenager’s own design. A precursor to the modern express rifle, the weapon was a double-barreled muzzle loader capable of hurling a three-ounce belted ball. The rifle weighed an imposing 21 pounds and could handle a charge of 16 drams of powder. Gibbs thought the overly powerful rifle preposterous. The weapon, dubbed “Baby,” would have crippled a mere mortal, but Baker was no normal man. When the rifle was fired, the savage recoil spun him around like a dervish, but through brute strength Baker eventually mastered the weapon.

Expeditions in the East

His father, a successful merchant, wanted his son to follow him into the commercial business, but two years in a stuffy office convinced Baker that there was more to life than trade. In 1845, wanting to pit his rifle against the largest beast known to man, Baker trekked to Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) in pursuit of elephants. To prepare for the hunt, he studied the great beasts’ skeletons in museums and anatomy textbooks and then applied his knowledge with deadly efficiency to bagging elephants, buffaloes, and leopards. The young explorer found tropical hunting an often life-threatening experience. “Jungle hunting was like shooting in the dark,” he later remarked. With the help of his brother John, he founded a mountaintop health resort at Nuwara Eliya for other English immigrants, and successfully raised choice breeds of cattle. Eventually, Baker’s Ceylon escapades landed on the pages of two books he authored: The Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon (1853) and Eight Years’ Wanderings in Ceylon (1855).

The books catapulted Baker to stardom as a gentleman of adventure. He followed them with a journey to Constantinople and the Crimea in 1856, and three years later he supervised the construction of a railway across the Dobrudja region of central Europe, linking the Danube with the Black Sea. Baker’s growing reputation caught the eye of the exiled Maharajah Duleep Singh, the so-called Black Prince of India, who invited Baker on a hunting trip for wild boar in the frigid recesses of the lower Danube.

The two became fast friends as they sailed down the ice-capped river. After knocking a hole in the bottom of their boat on an ice floe, the friends put into Viddin, in modern-day Bulgaria, for repairs. There, Baker met his future wife, Transylvania-born Florence Szasz, under highly romantic circumstances. The 14-year-old Florence had been kidnapped as a child and raised in an Ottoman harem; she was about to be sold to the local pasha. Smitten with the sad-eyed girl, Baker launched into the bidding and won his future wife and lifelong companion. The pasha was enraged and his cavalry pursued the trio all the way to Bucharest.

The glamorous young couple quickly became a Victorian sensation, traveling the world living out breathtaking, swashbuckling adventures. In 1861, they dashed off to Cairo on an expedition to discover the Holy Grail of Victorian explorers—the source of the Nile. The couple fled marauding hippopotamuses, battled hostile tribesmen, and outwitted unscrupulous Arab slavers. They explored the Atbara and other Nile tributaries, and in Khartoum they met fellow explorers John Hanning Speke and James Augustus Grant, who had already discovered the major source of the Nile in newly named Lake Victoria. The Bakers despaired of finding similar fame, but Speke and Grant collegially told them of another lake through which the Nile flowed, and the Bakers traced the river back to the Nyanza, which they renamed Lake Albert after Prince Albert of England. Upon their return to England in October 1865, they found themselves even greater celebrities, with a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society and a knighthood awaiting Baker. They also took the time to formalize their hitherto unorthodox relationship, marrying in Piccadilly’s Church of St. James on November 4.

The Forty Thieves

In 1869, the Prince of Wales (future King Edward VII) and Princess Alexandra toured Cairo at the behest of Turkish Khedive Ismail, who ruled the country. Their guide was the recently knighted Sir Samuel White Baker. The prince and princess fell in love with the debonair adventurer—Queen Victoria was a little more skeptical about Baker’s premarriage shenanigans. At their behest, Baker accompanied them to Ismail’s grand masked ball. The khedive used the opportunity to propose a plan for exterminating the slave trade in the Sudan. The royal couple agreed, insisting that Baker was the very man to lead the expedition.

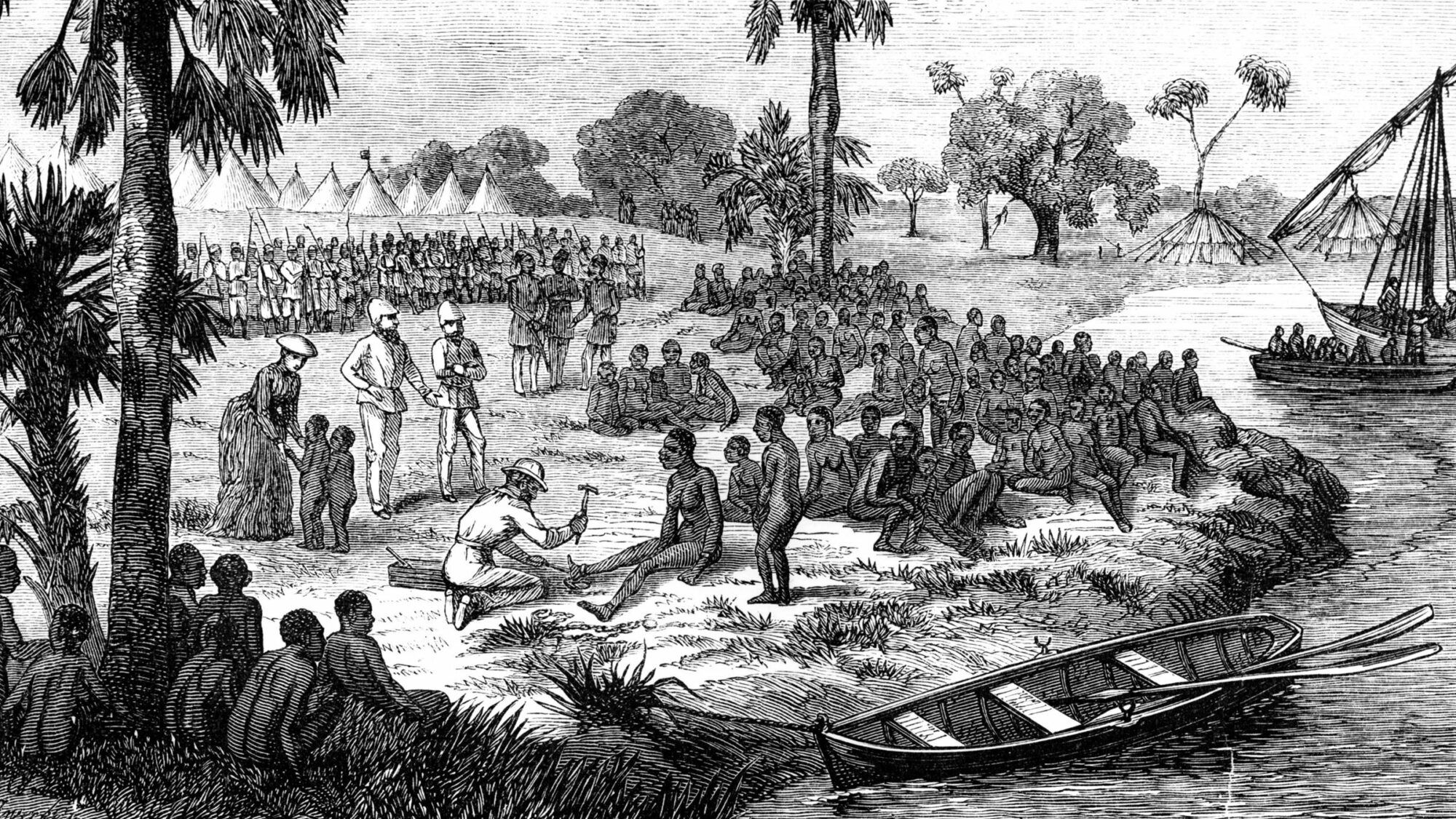

The contract stipulated that Baker would have unlimited powers, with the rank of pasha and governor general of the Equatorial Nile Basin, for four years. His forces consisted of 1,645 men subdivided into two musket-armed infantry regiments, two artillery batteries, and one “very irregular” tribal cavalry unit. One infantry regiment was composed entirely of convicted Egyptian rapists and murderers, while the other was manned by experienced Sudanese veterans who had fought in Mexico under the French.

From these two groups Baker handpicked 46 of the strongest men for an elite personal bodyguard, which he aptly named the Forty Thieves. Baker drilled the group in marksmanship, hand-to-hand combat, and British battle formations. He ensured their unflinching loyalty by increasing their wages, dressing them in brilliant red uniforms over Zouave trousers, and arming them with Snider breech-loading rifles.

Through his years of experience in the African interior, Baker knew that it would be impossible to supply his army by camel train alone. For that reason, he had 15 sloops, six steamships, and 15 diahbiahs, commanded by civil engineer Edwin Higginbotham, dismantled and carried over the desert on 1,000 pack camels to the Nile, where they were reassembled near Khartoum. With the equipment in place, the expedition, accompanied as always by Florence, set out for Khartoum. In February 1870, the army left Khartoum and steamed 648 miles toward Gondokoro, where it ran straight into an impenetrable marsh barrier known as the Sudd. Native guides suggested that they go around the blockage on the Bahr Giraffe, a small tributary of the Nile. With the waters of the river quickly receding, the expedition was now in a race against time. The party found the Bahr Giraffe impassable, and to make matters worse, they had arrived at the height of malaria season. Baker ordered his men to dredge the river amid clouds of buzzing mosquitoes, crocodiles, and poisonous snakes.

Battling the Bari

On May 26, Baker finally reached Gondokoro, the heart of Bari tribal territory. The Bari were fierce warriors allied with the Arab slavers. They fought in the nude and were organized into clans known as dungesi, which could contain as many as 700 men or as few as 20. The clans rarely united to form a cohesive army. Instead, they fought as independent units, armed with spears and fiendishly barbed arrows. To combat these bellicose clans, Baker constructed an ad hoc military outpost he dubbed Ismailia.

At first, the tribesmen did not openly resist. They ignored the fort and continued to raid neighboring tribes for slaves. To punish them, Baker seized the tribe’s cattle, and open warfare erupted. Masters of the ambush, the Bari crept up to the edge of the camp and murdered unwary stragglers in the night. Fortunately, Baker’s eight years of jungle hunting paid off. Under his direction, the Forty Thieves set decoys to snare any Bari who came within rifle range.

The hit-and-run guerrilla war raged on until Baker realized that pacification could be achieved only through control of the food supply. With this tactic in mind, the army launched a 35-day campaign of nonstop fighting against the tribe. With the goal of capturing grain rather than killing combatants, they surrounded each village in turn and then stormed it at bayonet point. Within weeks, the army controlled the majority of the Bari’s corn supply.

Desperate, the starving Bari allied with their traditional enemies, the Lotuka, and descended on Baker’s camp with more than 1,200 warriors, while Baker was raiding on the opposite side of the Nile. Baker had left the inexperienced Colonel Raouf Bey in control of the garrison. Raouf Bey managed to beat back the tribesmen after several hours of prolonged musket fire, but he neglected to use the fort’s 81/4-pound howitzer because he had, he admitted later, “forgotten its existence.” The failed attack crippled the famished Bari, causing them to lose the will to fight. Baker seized the opportunity by exchanging several elephants he had shot in return for the emaciated tribe’s unconditional surrender.

Underestimating a Mighty Foe

With the pacification of the Bari accomplished, Sam and Florence left Bey behind with a garrison of 340 men and steamed southward on the Nile with a meager force of only 212 men. Along the way, Baker left another 100 men in Madi territory to protect the frail tribe from slavers. The small army continued due south on a collision course with the powerful kingdom of Bunyoro. The Bunyoro was a potent slave trading African principality led by Kabba Rega, a man whose father had attempted to kidnap Florence on Baker’s Nile expedition 10 years earlier. Still smarting from that attempt, Baker wanted to settle the score with Kabba Rega, whom he described as “cowardly, cruel, cunning and treacherous to the last degree.”

In his haste for revenge, Baker failed to take into account the king’s military genius. An African Machiavelli, Kabba Rega had unified the Bunyoro clans after the death of his father through a combination of diplomacy and military might. His vast army was headed by his crack royal guard, the 1,000-strong Bonosoora. Savage fighters, the Bonosoora wore leopard skins and terrifying antelope horn headdresses. Because many Bonosoora had acquired muskets from the Arab slavers, the cadre possessed the firepower necessary to put Baker’s Forty Thieves to the ultimate test.

Ignoring the monarch’s strength, Baker settled in for a protracted campaign by constructing a fortress outside the Bunyoro capital of Masindi. On the morning of March 31, Baker drilled the Forty Thieves outside the compound. In the distance, war drums reverberated and horns trumpeted. Within moments, thousands of screaming warriors engulfed Baker’s men, who quickly formed a square and fixed their bayonets. The Bunyoro were perplexed by the bristling iron hedgehog that gleamed before them. In the face of such overwhelming odds, Baker knew that his only hope rested back at the compound. Sensing the Bunyoro’s trepidation, Baker sounded the charge and the Forty Thieves ran over the stunned tribesmen.

Upon hearing the uproar, Florence organized the camp by arming every able-bodied man. She commanded the infirm to load the rifles, pistols, and shotguns for the active combatants. A smaller force of Bunyoro fell upon the camp, but under Florence’s stalwart command they were beaten back. When the Forty Thieves returned, they fortified the position with earthwork ramparts, palisades, and ditches. However, they were woefully unprepared for a siege. Low on food, the force could not last a month. Realizing this, the duplicitous Kabba Rega feigned surrender and offered the garrison poisoned plantain cider as a sign of goodwill. The famished troopers gulped down the swill and nearly 50 men immediately fell ill. The quick-thinking Baker saved their lives by immediately dosing them with a vomit-inducing tartar emetic.

The Long Retreat

A day later, as the Bakers and the Forty Thieves foraged for supplies in Masindi, they fell under heavy tribal musket fire that dropped several of the elite cadre. Meanwhile, thousands of Bunyoro spearmen, led by the crack Bonosoora, streamed through the grasses like an angry swarm of fire ants. Under a hail of shot, Baker’s men formed a square and unloaded with their rapid-firing Sniders. The tribesmen fled while Baker’s troopers put the capital village to the torch.

With Masindi in ruins, Baker dismantled the camp and burned everything except the essentials. The only escape route to be found was a grueling 100-mile march to Foweera, the capital city of King Rionga, a rival claimant to the Bunyoro throne. Luckily for the company, Florence was prepared. Over the course of several months, she had stockpiled several crates of flour, more than enough for the journey to Foweera. The small force tightened their belts, oiled their rifles, and double-timed to Rionga’s capital. Baker carried Baby, a Purdy shotgun, and a brace of double-barreled tiger-hunting pistols. Florence packed a revolver on her hip with a reserve of ammunition secreted in her shirt.

The column fought its way toward Foweera for seven days, under the relentless pounding of musket balls, poisoned arrows, and iron spears. The high grasses necessitated that Baker split the column into three parties, each controlled by a bugler who would give the command to either halt, cease fire, or advance. The famished column stumbled forward, suffering heavy losses. Baker’s men eventually reached Foweera, but they were startled to find a smoldering heap of ashes. Girded for more trouble, the troops dug in to face the final overwhelming onslaught as war drums pounded in the distance and the Bunyoro closed in.

At the darkest possible moment, when all seemed lost, Rionga sent word that his armies had arrived—the column was saved. Kabba Rega would not dare attack the heavily armed men in the heart of enemy territory. Nevertheless, Baker had effectively been defeated. His army numbered fewer than 95 men, and his four-year contract was set to expire. Before leaving he constructed a fortress on the outskirts of Bunyoro territory; then he and Florence withdrew northward to Cairo. Although Baker’s expedition, in the end, was a failure, he laid the groundwork for the eventual suppression of the slave trade by General Charles “Chinese” Gordon, who employed many of the forts Baker had constructed as bases of operation. Gordon did not have long to enjoy his triumph—in January 1885 he was killed and beheaded at Khartoum by followers of the radical Muslim leader, the Mahdi. Kabba Rega himself defied colonization for nearly 30 years, pitting his native forces against Maxim guns, frontline Egyptian troops, and British regulars.

National Heroes

The Bakers retired to England, where they were hailed as national heroes. They purchased an estate in south Devon, Sandford Orleigh, and Baker wrote a book, Ismailia, recounting his slave-trade adventures. In 1879, he visited Cyprus for another travel book, Cyprus as I Saw It. The couple spent several winters in Egypt and also traveled and hunted extensively in India, Japan, and the Rocky Mountains of the United States. In 1890, Baker published his last book, Wild Beasts and Their Ways. Ironically, the stalwart adventurer died quietly at home in Florence’s arms in December 1893, at the age of 72.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments