By Al Hemingway

On the morning of September 2, 1649, peering over the immense 20-foot-high wall that surrounded the Irish city of Drogheda, English Royalist general Sir Arthur Aston did not like what he saw. Arrayed before him was a large Protestant army under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell, who had arrived in the country a few weeks earlier like an avenging angel—or devil. With the help of 11 massive 48-pounder siege guns delivered up the Boyne River by a fleet of English warships helmed by Sir George Ayscue, Cromwell intended to pound the rebellious Irish and their Royalist allies into submission.

Ireland Joins in the English Civil War

Ireland had been at war with England, off and on, since 1641. Throughout that period, the English government had also experienced problems at home. In 1642, open civil war had erupted between the forces of Parliament and the supporters of King Charles I. For the next seven years, the two sides fought a series of pitched battles for control of the country. Finally, on January 30, 1649, the captured king was beheaded in London and his son, Charles II, desperately fled the country for the European continent. Almost immediately, Charles II signed a pact with Irish confederates to join forces with them to retake England and restore the monarchy.

The English Parliament moved quickly to quell the unrest in Ireland. This would prove to be an arduous task. More than 80 percent of the country was held by Irish Catholics and their Royalist partners. Parliament fully understood that this threat to their power had to be eradicated. They appointed rising strongman Oliver Cromwell, a stern and merciless hero of the English Civil War, lord lieutenant of Ireland and ordered him to handle the task. Cromwell, in turn, gathered an impressive army of 8,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry and a large artillery train that included several heavy siege guns. “Ironsides,” as Cromwell was called by admirers, counted on other soldiers already in Ireland to rally to his assistance when he arrived.

Cromwell’s Practical Approach

Cromwell was correct in his assumptions. Lt. Gen. Michael Jones had arrived in Ireland in 1647 with a 5,500-man expeditionary force to battle the Irish rebels. When Royalist commander James Butler, the Earl of Ormonde, moved to seize Baggotrath Castle, located between Dublin and Rathmines, Jones wasted no time in moving to defeat him. On August 2, 1649—just 10 days before Cromwell arrived in Ireland—Jones inflicted a humiliating defeat on Ormonde at Rathmines. More than 600 of Ormonde’s men were killed and another 2,500 taken prisoner. Most of his artillery was captured as well, along with his personal papers and journals. Jones’s dazzling victory secured a port for Cromwell’s army to land safely.

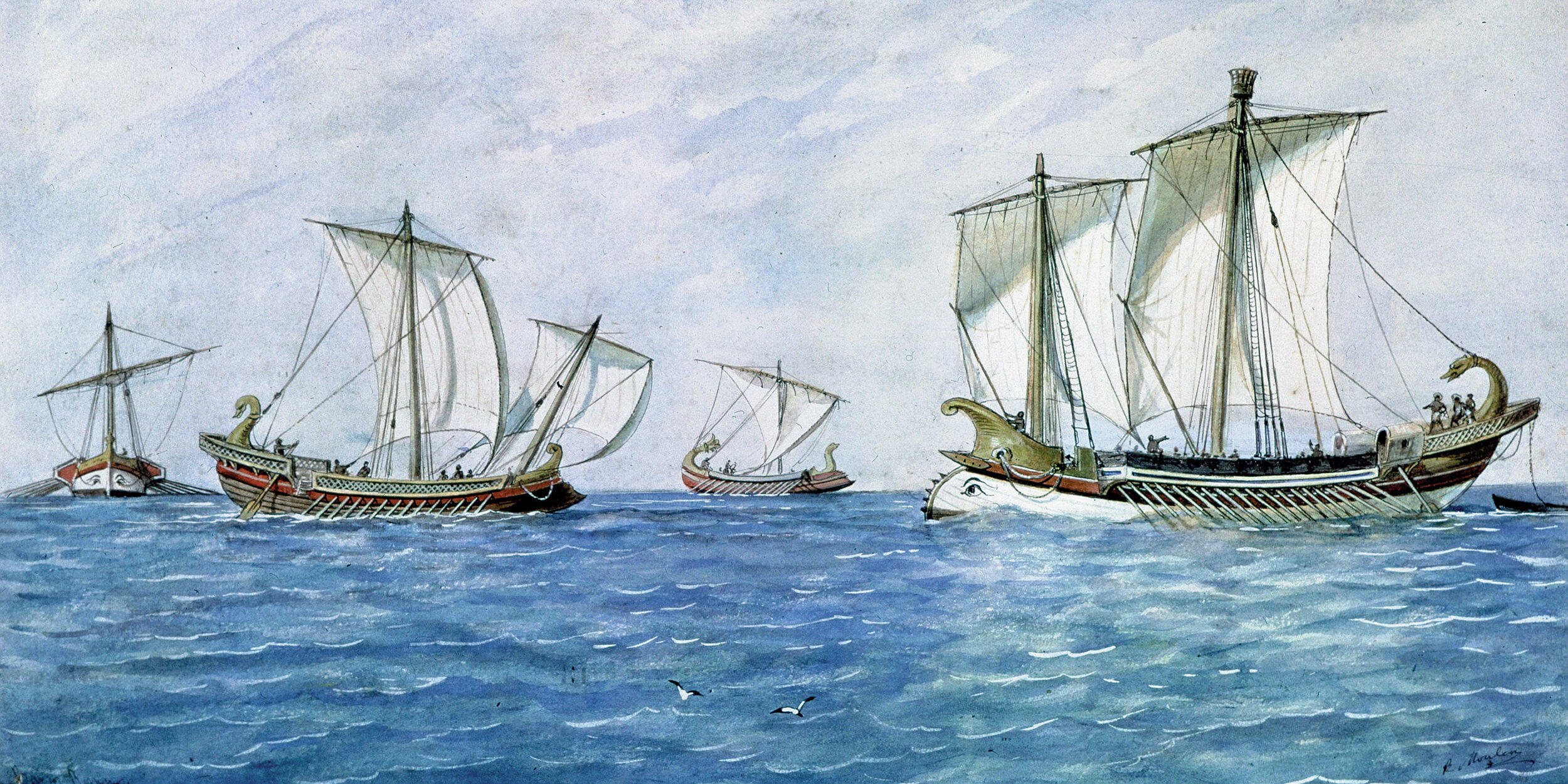

On August 15, the deafening roar of cannon filled the air as an armada of 35 English ships sailed unchallenged into the harbor at Ringsend, not far from Dublin. A few days later Cromwell’s son-in-law, Henry Ireton, followed with an additional 77 vessels. From there, the party advanced to Dublin, where Cromwell was warmly greeted (Jones already had driven the loyal Irish out of Dublin). The formidable Cromwell addressed the remaining citizens concerning his mission to Ireland. He vowed to restore to the Irish and Anglo-Irish Protestants “their just liberty and property,” both of which had been lost after the 1641 revolt. He further assured his supporters, many of them absentee landowners from England who claimed title to large swaths of Irish land, that he and his men were prepared to undertake “the great work against the barbarous and bloodthirsty Irish, and the rest of their adherents and confederates.” He promised that the “bleeding nation” would be restored “to its former happiness and tranquility,” under the “favor and protection from the Parliament of England.”

Despite his inherent disdain for the Irish, whom he considered “a priest-ridden, drunken, barbarous, vicious bunch of men,” Cromwell was no fool. He fully realized that he needed the peasants residing in the countryside to remain neutral—or at least placid—and not interfere with his army’s movements. He immediately established an edict forbidding his soldiers from harming what he somewhat condescendingly termed the “country people.” He assured the peasants that they could sell their wares at market without any hindrance from his occupying force. To show that he meant business—he always meant business—Cromwell hanged five soldiers for stealing chickens during the initial advance. His practicality would reap immeasurable dividends in the weeks to come.

Drogheda: the Beginning of a Bloody Campaign

To begin his conquest of Ireland, Cromwell eyed as his first prize the walled city of Drogheda, located 30 miles due north of Dublin at the mouth of the Boyne River. In early September, his contingent of Roundheads (Puritans who cropped their hair) set out to seize the city, whose name in Gaelic means “the bridge of the ford.” Justifying its keystone name, Drogheda was important for several reasons. From its port, huge quantities of butter and eggs were shipped to England. It housed many linen producers and also nurtured a large farming district. It was also located just south of Ulster, a hotbed of Royalist activity. Eight years earlier, the city had endured a three-month-long siege by Irish rebels. Ironically, English forces had broken the siege and relieved the townsmen.

Convinced that he was on a divine mission to rid Ireland of Catholic heretics and Royalist holdouts, Cromwell led his formidable and battle-tested New Model Army toward the city with revenge on his mind. Coupled with the fact he had not had a good ocean voyage (he was seasick most of the time), his bilious mood set the stage for the upcoming battle. Behind him trailed eight full infantry and six cavalry regiments, along with a long artillery train containing 11 siege guns and 12 field pieces. Iron-disciplined and well-equipped, the New Model Army had grown from Cromwell’s original cavalry unit, dubbed “the Ironsides” for their armored horses. Like their commander, the soldiers were rock-ribbed Puritans who did not drink, swear, or blaspheme. The army was remarkably democratic for its time, drawing its officers from a wide spectrum of tradesmen and craftsmen. Most of the aristocrats had followed the king, and many had died before him in a series of losing battles against the Protestant host.

Drogheda, ironically, was an English-favoring city whose streets and canals reminded one visitor of a Dutch town, “fair and commodious.” It was actually two cities in one, completely surrounded by a 20-foot-high stone wall, 11/2 miles long and six feet thick. The wall tapered to two feet at the top to enable defenders to stand on its ramparts and fire down on attackers. Numerous guard towers were strategically placed all along the formidable wall to repel any attack. Separating the two cities was the River Boyne, which snaked its way from west to east. In the southern sector, a heavily populated residential area stood upon a hill. In the southeast was St. Mary’s Church, which was virtually embedded in the wall surrounding city. The structure boasted a towering steeple that commanded a spectacular view of the countryside. From this position, lookouts could see any approaching army. Running alongside the entire eastern wall of the southern end of the town was a precipitous gully called the Dale, which residents used as convenient garbage dump. Northwest of St. Mary’s Church was the Mill Mount, a horseshoe-shaped, manmade hill that was also used as a fortification.

The northern area of Drogheda was laced with narrow cobblestone streets. Situated in the northeastern part of town was St. Peter’s Church. Directly north of it was the St. Sunday Steeple. As with its southern neighbor, the massive wall was lined with lookout towers and seemingly impregnable gates. A drawbridge spanned the river, connecting the two parts of the city.

“Colonel Hunger and Major Sickness”

Commanding the Royalist garrison at Drogheda was Sir Arthur Aston, a veteran of numerous battles against the Turks in Poland and against his own countrymen during the English Civil War. Although a Catholic, Aston had risen to become governor of Oxford in 1643. Unfortunately for him, Aston was not well liked by the residents of the ancient university town, or even by his own men. His harsh and domineering attitude toward the civilian population did not endear him to them, and he was placed under house arrest after he physically accosted the mayor of the town in 1644. Aston was finally relieved as governor after his leg had to be amputated following a riding accident.

Aston immediately went to Ireland and took up arms with the rebel forces under Ormonde, who envisioned the country as a new Royalist power base. With an army of 3,000 men, many of whom were English Catholics, the Protestant-born Ormonde appointed Aston governor of Drogheda and ordered him to defend the city while Ormonde reorganized the army in the wake of the Rathmines debacle. Aston had his men construct three parallel ditches, each 150 yards long, astride the road to Dublin. The new defensive works would delay an enemy advance long enough to give defenders a better chance of repulsing the attack. The trenches were also deep enough to stop the cavalry in its tracks—a particular consideration given Cromwell’s well-earned reputation as a commander of horse.

Confident that he could defeat Cromwell despite being outnumbered 4-to-1, Aston bragged: “He who could take Drogheda could take Hell.” Aston figured that Drogheda’s superior position, coupled with the undesirable effects of a long siege, would fatally weaken Cromwell’s forces. As Ormonde put it, “Colonel Hunger and Major Sickness” would play a pivotal role in demoralizing the Parliamentarian forces camped outside the city’s gates.

Despite these important factors and Aston’s outward display of bravado, the governor faced several serious problems of his own. Ormonde could not afford to bolster the contingent at Drogheda, and Aston was running low on supplies and weapons. More ominously, numerous citizens within the city’s walls failed to rally behind the Royalists, including Aston’s own grandmother, Lady Wilmot, who even concocted a “ladies’ plot” to undermine her own grandson. When Aston discovered his relative’s disloyalty, he ordered her to leave Drogheda posthaste before he “made powder of her.” Ormonde quickly interceded in the family matter and sent the old woman away safely out of “the consideration and respect we retain for her years and quality.”

The Regulations of War

Cromwell had no intention of enduring a costly and lengthy siege at the walls of Drogheda. Familiar with lightning-fast cavalry tactics, “Ironsides” had little experience with siege warfare. Even if he had, Cromwell could little afford to be delayed at Drogheda. Winter was fast approaching and Cromwell wanted to achieve his conquest of Ireland with the least number of casualties among his troops, whether from battle injuries or the wide variety of ailments they would be exposed to in the cold, damp weather.

On September 10, Cromwell sent a proclamation to Aston demanding the capitulation of Drogheda. The message read bluntly: “Sir, having brought the army of the Parliament of England before this place, to reduce it to obedience, I thought it fit to summon you to deliver the same into my hands to their use. If this be refused, you will have no cause to blame me. I expect your answer and remain your servant, O. Cromwell.”

Aston wasted no time in refusing to surrender the city. The rules of warfare during that period were explicit; if an army would not relinquish a city under siege, then no quarter would be given to the defenders if the town was captured by the attackers. The prevailing logic dictated that many lives would be spared by avoiding a long, drawn-out affair. The regulations of war were introduced to protect soldiers, not civilians, and the situation of the civilian inhabitants of Drogheda could best be described as highly vulnerable. As for the soldiers, they understood to a man that refusing to surrender during a siege made them fair game to their attackers. They had no reason to expect anything less from the grim Puritans swarming industriously outside the walls.

Aston, however, was adamant about not relinquishing Drogheda. He informed Ormonde that he and his officers “were unanimous in their resolution to perish rather than to deliver up the place.” Cromwell quickly answered Aston’s reply by lowering the white flag of truce and raising the red one of battle. The stage was set for one of the bloodiest and most controversial days in Irish history.

Hammering the Defenders

The English gunners rolled one battery of long-range 48-pounder siege guns into position at the southern end of the town and concentrated their fire on the wall situated between the Duleek Gate and St. Mary’s Church. Cromwell wanted the imposing tower obliterated quickly to prevent the rebels from observing the movement of his troops. A second battery of artillery was brought up to lob shells east of St. Mary’s Cathedral. Cromwell hoped that his guns could weaken the stone walls and enable his soldiers to assault the southeast corner of Drogheda. If the cannonade could punch some openings into the thick walls, Cromwell vowed, then he and his army would “do our utmost the next day to make such breaches assaultable, and by the help of God to storm them.”

By five o’clock the following afternoon, the English artillery pieces had toppled the imposing steeple of St. Mary’s Church. The projectiles had also created some small gaps in the southern and eastern bulwarks themselves. Seizing the first opportunity, Cromwell gave the order to advance through the breaches and take the town. Colonel James Castle, leading an infantry regiment, struck the southern portion of the wall. Meanwhile, Colonel Isaac Ewer’s men lent support. Colonel John Hewson’s soldiers set out across the Dale and assaulted the same position from an easterly direction. Protestant horsemen ranged north of the city to prevent any last-minute reinforcements from Ormonde.

“No Quarter! No Quarter”

Despite the attackers’ superiority in numbers, the defenders repelled two vicious assaults from the Roundheads. Hewson’s men were driven back across the ravine but, realizing he was in serious trouble, the other two units came to his aid. The fighting was hand-to-hand as the Parliamentarians forced their way through the breaches. Because the openings were small, the cavalry could not get through to support the infantry. The attack suddenly faltered when Colonel Castle was struck in the head by a bullet and killed. Enraged, “Ironsides” himself led the next charge through the opening, climbing down from his horse and swinging a blood-stained sword right and left as he advanced wild-eyed into the fray. As Ewer’s troops came up to reinforce the others, the Parliamentarians poured through the breach and entered the town.

On the Royalist side, Colonel William Wall, a popular leader, was killed. With his death, many defenders lost heart and began laying down their arms. Ormonde heard later that some form of pardon had been promised to the soldiers and officers if they surrendered, a point that has been argued by historians ever since. Unfortunately for the defenders, the rules of no quarter had been irrevocably established when Aston refused Cromwell’s offer a day earlier, and even if a suggestion of clemency had been put to him, Cromwell would never have agreed. Instead, in a white heat of passion, he screamed to his men: “No quarter! No quarter!” With so many of his own men and officers dead or wounded, Cromwell wanted revenge.

Aston and some 250 of his followers found refuge in the Mill Mount and fought on. An informal parley began, with Aston negotiating for the safe surrender of company-grade officers. (It is unclear whether he included himself in the offer.) Once again, Cromwell nixed any proffer of mercy, ordering a new attack. Overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of Cromwell’s men, Aston and his men were all cut down. Aston was beaten to death with his wooden leg, which Cromwell’s soldiers had mistakenly believed was filled with gold coins. Enraged to find that it was solid wood, the Roundheads put it to deadly use. They did not go away entirely empty-handed—a money belt containing 200 gold sovereigns was found on Aston’s corpse.

By this time, thousands of Roundheads were running through the streets of Drogheda, making their way into the northern section of the city. The retreating army realized too late that their comrades had failed to raise the drawbridge to block the enemy advance. Cromwell issued new orders to kill anyone who was found to be armed, while positioning his cavalry outside the northern walls to prohibit anyone from escaping the slaughter taking place within.

Catholic clergymen were given no special treatment; they were summarily executed on the spot. Approximately 100 priests and defenders made their way to St. Peter’s Church in the northern part of Drogheda, taking refuge in the steeple. Cromwell told his men to gather the wooden pews from inside the cathedral and set them ablaze to burn the occupants from their sanctuary. As the flames crept skyward, some tried to flee, but they were run through with swords or speared with pikes. The remainder perished in the roaring fire. As the screams of the dying permeated the air, one unfortunate individual was heard to exclaim: “God damn me, God confound me; I burn, I burn!” A more enterprising soul leaped from the tower and landed heavily, but miraculously suffered only a broken leg. Cromwell was so astonished by the man’s bravery that he pardoned him on the spot “for the extraordinariness of the thing,”

Many innocent civilians died during the massacre. Anthony Wood, a Parliamentarian officer, later said that he had discovered numerous women hiding in a church, the “flower and choicest of the women and ladies belonging to the town: amongst whom, a most handsome virgin, arrayed in costly and gorgeous apparel, kneeled down to him with tears and prayers to save her life.” Overcome with pity, Wood displayed mercy and tried to protect her as they left the building. Suddenly, one Roundhead rushed the female captive and “thrust his sword into her body,” killing the young woman instantly. Wood’s compassion was short-lived—he rifled the body for any money and jewelry and then “flung her down over the rocks.” Wood also described how his soldiers picked up children and used them as human shields “to save themselves from being shot or brained” while they ascended the lofts and galleries of the church.

By dusk the majority of the Royalist forces had been killed or captured, with the exception of a few survivors skulking atop the towers and walls. Originally, these soldiers were not pursued, Cromwell assuming that they would eventually give themselves up when they became hungry and tired. Some of these defenders, however, had no intention of surrendering and fired down on the Roundheads, killing and wounding several. When the small group finally capitulated, Cromwell’s orders were quick and unmerciful. “Their officers were knocked on the head, and every tenth man of the soldiers killed, and the rest shipped for the Barbadoes,” Cromwell later wrote in a letter to Parliament. An untold number of prisoners, probably several dozen, spent the rest of their lives as white slaves on West Indies sugar plantations.

Following the battle, a handful of English Royalist officers were singled out for special punishment. Lt. Col. Edmund Verney, after surrendering, was removed from Cromwell’s immediate presence and stabbed to death. Another Drogheda defender, Colonel Michael Byrne, was invited to dine with the newly installed English governor, Lord Henry Moore. At the close of the meal, one of Cromwell’s officers bent down and whispered into Byrne’s ear. Byrne rose quietly to leave the table. When Moore’s wife asked innocently where he was going, Byrne replied with perfect gentlemanly composure: “Madam, to die.”

The Strategic Outcome of the Slaughter

Figures vary, but somewhere between 2,000 and 4,000 Irish and Royalist soldiers and civilians died at Drogheda. Cromwell’s army suffered 150 killed and an unknown number wounded. Cromwell later justified the slaughter in a letter to William Lenthall, speaker of the Parliament, by saying that the victory at Drogheda belonged to the Almighty. “I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches,” Cromwell wrote to Lenthall, “who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood for the future, which are the satisfactory grounds to such actions, which otherwise cannot but work remorse and regret.”

Cromwell’s strategy was brutally simple. By giving no quarter to the enemy, he believed that other Irish towns in his path would waste no time in laying down their arms to avoid further bloodshed. In the beginning, the plan worked extremely well. The slaughter at Drogheda had a tremendous negative impact upon the Irish, at least for the time being. Immediately following Drogheda, the towns of Trim, Dundalk, Carlingford, and Newry all surrendered without a struggle.

At the same time, Ormonde had a difficult time convincing his troops to fight Cromwell’s soldiers and defend their country. “It is not to be imagined how great the terror is that those successes and the power of the rebels [the English] have struck into this people,” he informed King Charles II. “They are yet so stupefied, that it is with great difficulty I can persuade them to act anything like men towards their own preservation.”

When Cromwell’s army reached Wexford, the Royalist commander there, David Sinnott, refused to give up the town without a fight. Once again, the Parliamentarians fought their way into the city (after an eight-day siege) and killed another 2,000 soldiers and citizens in the marketplace. Cromwell left Ireland soon afterward, leaving behind a distinctly mixed legacy. For Irish Catholics and English Royalists, the slaughter of innocents at Drogheda and Wexford took on the air of religious martyrdom. Stories spread throughout the countryside of the wicked English commander who butchered women and children with no remorse. When the news reached England, however, the population was overjoyed and declared a day of thanksgiving to celebrate the fact that the heinous Irish rebels had received their just rewards.

“Curse of Cromwell”: Drogheda Remembered

Historians have argued that the stern but upright Cromwell who had fought in England and Scotland during the civil war was not the same bloodthirsty tyrant who conducted the Irish campaign. Cromwell biographer Antonia Fraser has written: “The conclusion cannot be escaped that Cromwell lost his self-control at Drogheda, literally saw red—the red of his comrades’ blood—after the failure of the first assaults.”

There is no doubt that Cromwell lost his self-control at Drogheda. His irrational actions, so unlike his earlier campaigns in England and Scotland, resulted in the deaths of hundreds of innocent civilians. “The death rate in military engagements in England was usually between five and 10 percent,” wrote John Morrill, professor of British and Irish History at the University of Cambridge and past president of the Oliver Cromwell Association. “At Drogheda and Wexford, it must have been 80 percent. By Cromwell’s own admission, these included non-combatants killed in the knowledge that they were non-combatants.”

His deep hatred for the Irish certainly clouded Cromwell’s judgment. Incensed by the massacre of Protestants in 1641 by Irish Catholics, Cromwell fervently believed that his mission was a divine one, sanctioned by God to deliver a just punishment upon the barbaric Irish. Ironically, many of the defenders of Drogheda were not Irish, but English Catholics. They almost certainly had not taken part in the killing of the Protestant settlers eight years before. This did not matter to Cromwell. In his mind, the inhabitants of the town were to blame for their own murders.

Some historians have claimed that Cromwell was well within his rights to deny quarter to the soldiers of Drogheda and Wexford because they had refused his petitions for surrender. One Cromwell defender has even claimed that some of the lurid tales of massacre that have been passed down through the centuries have been fabricated. He points to the fact that the remains of the dead have never been found. Most historians, however, vehemently disagree with that assessment. “There may have been good military reasons for behaving as he did, but they were not the motives which encouraged him at Drogheda, during the day and night of organised butchery,” historian Eugene Coyle has concluded. “Cromwell knew exactly what he was doing at Drogheda whether the order for ‘no quarter’ was given or not.”

Heated emotions are still very much in evidence in Ireland today whenever Cromwell’s name is brought up in conversation. On the 400th anniversary of his birth on April 25, 1999, protesters picketed celebrations of the event. To this day, the “Curse of Cromwell” looms like an evil specter between the two countries. As English author G.K. Chesterton once remarked, “The tragedy of the English conquest of Ireland in the 17th century is that the Irish can never forget it and the English can never remember it.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments