By William E. Welsh

By May 1941, the German Luftwaffe’s fortunes had risen to great heights and plummeted to equally startling depths in the course of a single year of blitzkrieg warfare in Western Europe. Led by the narcissistic Hermann Göring, a former World War I flying ace, the Luftwaffe had been the perfect complement to the land-based Wehrmacht in the opening months of the war. In Scandinavia and the Low Countries in the spring of 1940, the Luftwaffe’s parachute light infantry, or Fallschirmjäger, had seized key objectives to speed the advance of Germany’s panzer forces, while high-level and dive bombers had hastened the capitulation of stubborn nations with the deliberate, unmerciful bombing of European cities that dared defy Adolf Hitler.

But Luftwaffe fortunes soured during the evacuation of Dunkirk and the ensuing Battle of Britain, when the air force failed to deliver promised victories. In the wake of the disastrous air war, Göring was like a gambler down on his luck. The Reichsmarschall was desperate to restore his prestige and that of his beloved Luftwaffe. The Royal Air Force may have gotten the better of the Luftwaffe in the skies over Britain, but Göring’s paratroopers were as yet undefeated. After Nazi forces surged into the Balkans in the spring of 1941 to redeem Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s misbegotten invasion of Greece, Göring hoped the Luftwaffe would have another opportunity to shine for the notoriously hard-to-please Führer.

For the Pride of the Luftwaffe

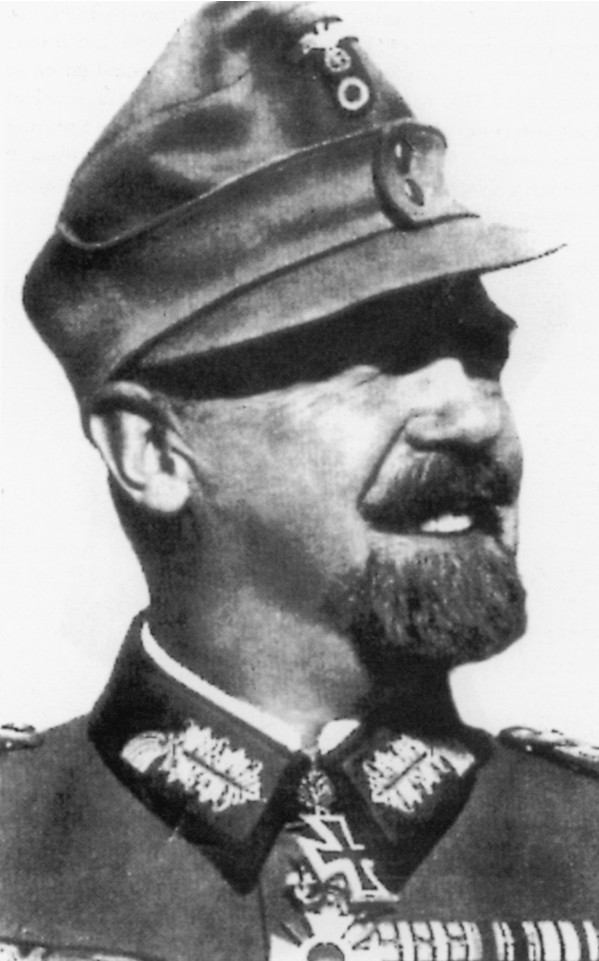

Lieutenant General Alexander Löhr, the commanding general of the Luftwaffe’s 4th Air Fleet, and Major General Kurt Student, commander of the XI Air Corps, presented plans for an invasion of Crete that would be conducted solely by Luftwaffe paratroopers. Göring was sold on the idea immediately. A successful airborne invasion of Crete would restore him to the Führer’s good graces. The stakes were high—Göring was betting that his airborne corps could conquer the strategic island with little or no assistance from the Wehrmacht.

The island, located 60 miles from the southernmost tip of mainland Greece, measures 160 miles east to west and ranges from 12 to 30 miles north to south. Its people live mostly on narrow strips of fertile land on the north and south shores. The fertile belts give way to foothills, which are overshadowed by volcanic mountains that soar to more than 8,000 feet. Its large size could accommodate multiple airfields, and an enormous natural harbor at Suda Bay could shelter a large number of vessels. Student’s plan for invading Crete was to make simultaneous drops at seven key objectives on the northern coast of the island and reinforce those bridgeheads while the separate groups linked up with each other. But Löhr wanted to concentrate the entire invasion on the western end of Crete, where Maleme airfield and the port of Suda were located, and then march east to capture the rest of the island.

To settle the dispute, Göring devised a compromise. Under the final plan for Operation Mercury, Student would command more than 22,000 troops, all of whom would participate in the invasion, either in the initial series of attacks or as reinforcements. Student’s XI Air Corps comprised the 7th Airborne Division as well as the 5th Mountain Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Julius Ringel. The latter replaced the 22nd Air Landing Division, which had been detached to guard the Romanian oil fields. The plan called for 750 troops, drawn from the parachute division, to land by glider, 9,250 by parachute, 5,000 to land on captured airfields, and 7,000 to arrive by sea. Since there were not enough transport aircraft to drop all of the paratroopers at once, two shuttles would be necessary. The plan was to drop the first wave shortly after daybreak and the second wave by mid-afternoon. The first would focus on capturing Maleme airfield, the capital city of Canea, and the port of Suda, while the second would concentrate on taking the Retimo and Heraklion airfields.

On the morning of the first day, the four battalions of the 7th Air Division’s Storm Regiment would descend on Maleme airfield by glider and parachute, while the 3rd Parachute Regiment would land near Canea, the capital of Crete, and capture it as well as the port of Suda. The air transport fleet of about 500 Junkers Ju-52s would then return to the mainland, where it would refuel and return with the remaining paratroopers six hours later. In the second wave, the 2nd Parachute Regiment would drop on Retimo, while the 1st Parachute Regiment would land atop Heraklion.

The attacking forces were divided into three groups. Brig. Gen. Eugene Meindl commanded the Storm Regiment that formed western group, Maj. Gen. Wilhelm Sussman commanded the 2nd and 3rd Parachute Regiments in the middle group, and Colonel Bruno Brauer commanded the 1st Parachute Regiment in the eastern group. On the second day, the 5th Mountain Division would be airlifted to the three captured airfields, and Axis convoys would land troops, tanks, artillery, and supplies at the deepwater ports of Suda Bay and Heraklion. The VIII Air Corps, under General Wolfram von Richthofen, would provide air support before and during the invasion, using 650 aircraft, including 280 medium bombers, 150 dive bombers, 180 fighters, and 40 reconnaissance planes.

By May 14, the units of the 7th Air Division had reported to the seven airfields from which they would be flown to Crete. The following day, regimental and battalion commanders were briefed by Student at his headquarters in the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. Although the glider landings and paratroop drops originally were scheduled for May 17, a delay in transporting 5,000 tons of aviation fuel by tanker through the Adriatic Sea forced Student to postpone the attack until May 20. To further complicate matters, the Germans had failed to accurately estimate the size of the enemy force on Crete, despite regular reconnaissance flights. Not until the final hours leading up to the invasion did Student and his men learn that the Allied force on Crete was four times larger than previous estimates of 10,000 troops.

When mainland Greece fell to the Germans in April, about 18,000 soldiers went to Crete, where they were joined by 12,000 fresh troops from Egypt. The Allied units were integrated, in theory, with 12,000 Greek troops divided into eight regiments, for a total troop strength of about 42,000. General Sir Archibald Wavell, the commander-in-chief of the British Middle East Command, flew to Crete on April 30 and immediately replaced General Maitland “Jumbo” Wilson with Maj. Gen. Bernard “Tiny” Freyberg, commander of the New Zealand Division, who had fought under Wilson on the Greek mainland. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent Wavell a message that made it clear the Allies would not give up the island without a fight. “It ought to be a fine opportunity for killing the parachute troops,” Churchill wrote. “The island must be stubbornly defended.”

“The Island Must be Stubbornly Defended”

Freyberg inherited a difficult situation. The Allied troops evacuated from Greece had abandoned nearly all of their vehicles and heavy weapons. On Crete, their meager arsenal consisted of 49 field guns, eight 3.7-inch howitzers, and 22 tanks. Air cover was nonexistent. Any aircraft that could still fly had returned to Egypt. The various positions around the island were unfortified, and most units were without radios. As for the Greeks, they were armed with antiquated rifles and as little as three rounds of ammunition each.

The British had several advantages, however, that might help them stall or even repel the Nazi invaders. Most important, they controlled the seas and therefore could intercept any German reinforcements, equipment, or supplies arriving by boat to the island. The Allies would also have more men on the ground during the first day of the battle than the Germans could drop from the sky. Thanks to Ultra, the name given to the deciphered German codes, Freyberg knew shortly after he arrived that the Germans were planning a massive airborne invasion aimed at capturing the three major airfields on the north coast of Crete at Maleme, Retimo, and Heraklion. British intelligence mistakenly believed that the Germans might storm the beaches in the Maleme sector with the help of the Italian Navy, but the Germans had no intention of mounting any sort of beach assault.

The Allied Plan

Believing that they would one day recapture the island if they lost it to the Germans, the Allies did not destroy the airfields to keep the enemy from using them. Instead, Freyberg selected five key objectives to defend. In addition to the three working airfields, he would also defend Canea and the port of Suda. Holding down Maleme was the New Zealand Division, consisting of the 4th, 5th, and 10th Brigades, along with the 1st, 6th, and 8th Greek Regiments. At Suda Bay, the defense consisted of the Mobile Naval Base Defence Organization under Maj. Gen. Eric Weston, reinforced by two Australian battalions and the 2nd Greek Regiment. In close proximity and guarding the capital of Canea were the 1st Battalion (Royal Welsh Fusiliers), the 1st Ranger Battalion, and the Northumberland Hussars. Freyberg’s headquarters was hidden in a quarry near Canea.

The Retimo sector some 31 miles east of Canea was commanded by Australian Brig. Gen. George Vasey. For the sector’s defense, he had his 19th Australian Brigade, three batteries of artillery, and the 4th and 5th Greek Regiments. Vasey controlled the brigade from his headquarters at Georgioupolis, located midway between Retimo and Suda Bay. Lt. Col. Ian Campbell of the 1st Australian Infantry Battalion led the Australians who would defend the sector against the initial attack. Another 30 miles eastward was the Heraklion sector commanded by Brig. Gen. B.H. Chappel, who would defend the town and airfield with his 14th Brigade, a battalion detached from the 19th Australian Brigade, and the 3rd and 7th Greek Regiments. Owing to the acute shortage of transport vehicles, the forces at Retimo and Heraklion would be on their own during the invasion.

The Airborne Invasion Begins

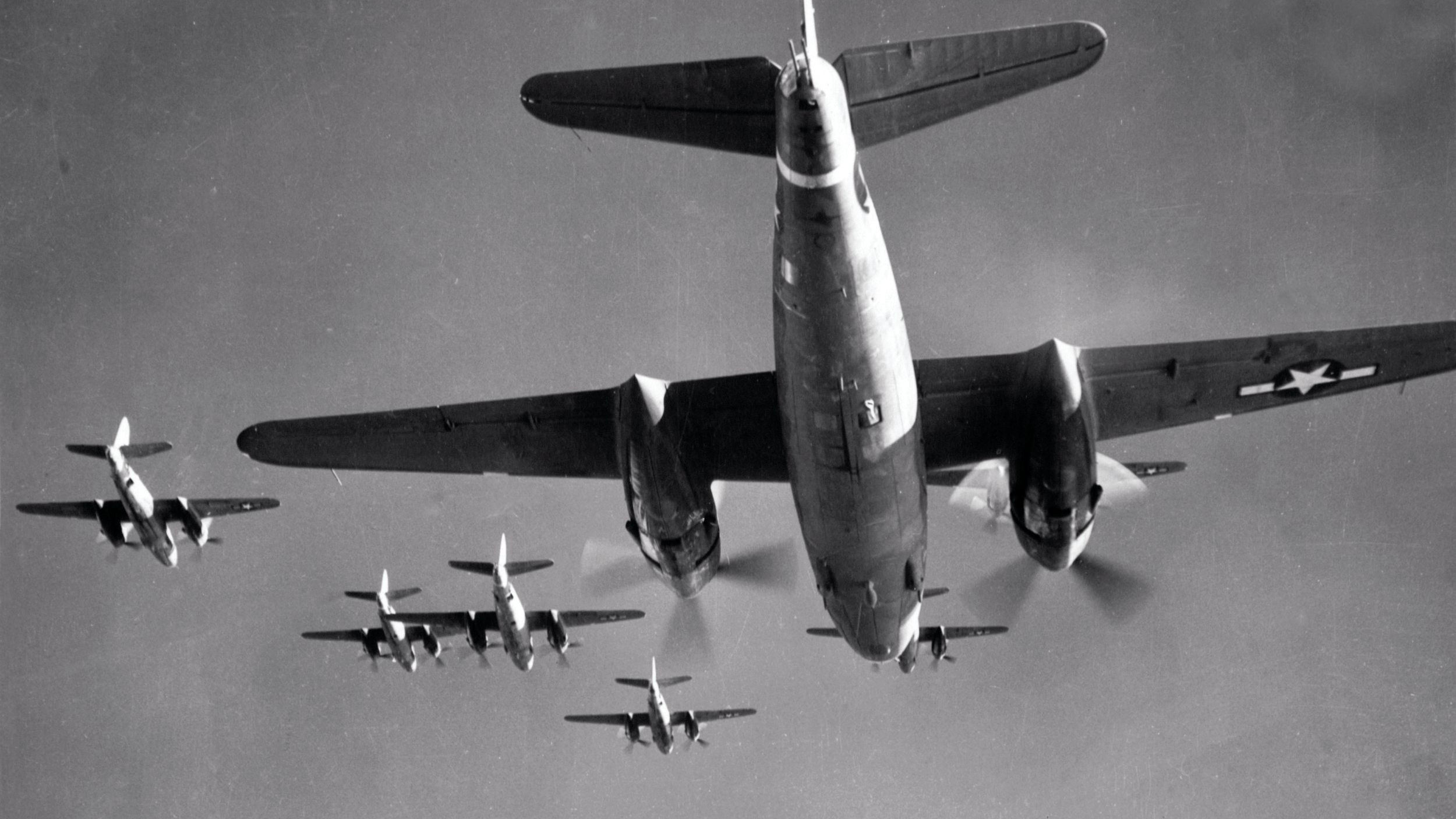

In the predawn darkness of May 20, the elite paratroopers of the German 7th Air Division boarded the transports and gliders at seven captured Greek airfields for the flight to Crete. Fifteen men boarded each of the 502 Ju-52s, while another 750 men climbed aboard 75 DFS-230 gliders that would whisk them to the ground fully outfitted to assault antiaircraft batteries and various key installations. At 4:30 am, the first of the heavily laden planes bounced down the makeshift runways in southern Greece. Not long after daybreak, the Luftwaffe began a series of bombing runs in preparation for the airborne assault. Hearing the drone of bombers high overhead, Allied troops raced for cover. They huddled in narrow slit trenches as bombs exploded atop their positions, sending white-hot shrapnel slicing through the air. Richthofen employed hundreds of medium bombers to soften up the targets for the first wave of the airborne assault. As soon as the bombers turned back, Stuka dive bombers and Messerschmitt 109s raced in seeking targets of opportunity.

The smoke and dust from the bombing had hardly cleared before Allied infantry stationed around the airfield spotted the gliders carrying elements of the Storm Regiment. One string of gliders touched down in the dry riverbed of the Tavronites, just outside the barbed wire from Lt. Col. L.W. Andrew’s 22nd New Zealand Battalion. Meanwhile, transport planes flew over the coastline and began releasing small specks into the sky that blossomed into parachutes in a dazzling array of colors—white, red, green, and yellow. The troops floated to earth under white parachutes, while chutes in other colors denoted weapons canisters, equipment, or supplies. The landscape erupted in small-arms fire. The New Zealanders blasted away at the gliders, killing many of the assault troops before they had a chance to exit the aircraft. One of the first casualties was Major Franz Braun, commander of the 3rd Glider Detachment. Despite the loss of Braun, the paratroopers attacked and captured the Tavronites bridge. Troops on both sides scrambled for cover and good fighting positions.

Assaulting Maleme Airfield

The capture of Maleme airfield was the sole responsibility of Meindl’s four-battalion Storm Regiment, which would arrive by both glider and parachutes. The Germans had plotted a three-pronged attack to capture Maleme. One group of paratroopers would land west of the Tavronites River, another group would land east of the airfield along the coast road, and a third group would land on Hill 107 directly south of the airfield. About two-thirds of the gliders, which formed a strike force known as Task Force Comet, would seize key objectives located adjacent to Maleme airfield. The men from the task force were drawn from Major Walter Koch’s 1st Battalion of the Storm Regiment.

The gliders carrying 2nd Lt. Wulff von Plessen’s 1st Glider Detachment, which was nearly identical in size to Braun’s, bounced to a landing directly behind a battery of Bofors guns at the river’s mouth. The paratroopers easily overwhelmed the gun crews, who were armed with only pistols. After disabling the guns, Plessen’s men advanced on the northern perimeter of the airfield but quickly found themselves pinned down by the soldiers of Company C of the 22nd New Zealand. While trying to disengage and retreat to German lines along the Tavronites, Plessen was struck and killed by enemy rifle fire.

At the same time that Braun’s force scraped to a landing in the riverbed, the gliders of Koch’s group and the headquarters of the Storm Regiment’s 1st Battalion swooped down onto Hill 107. Fifteen gliders under Koch angled for the southwest slope of the hill, while another 15 gliders touched down on the northeast slope. The glider in which Koch was seated clipped a stone wall, spun around in a circle, and split in half. Despite suffering a severe head wound during the landing, Koch took personal control of the situation, dispatching runners to instruct the paratroopers on his side of the hill to assemble near the wreckage of his glider in a protected seam in the hillside. Like the two other glider groups that landed near Maleme, Koch’s paratroopers took heavy fire from the New Zealanders. The losses in Koch’s group were so severe that only 25 paratroopers of the 150 who had landed on the southwest side of the hill gathered with Koch in a feeble attempt to storm the hill. The attack was broken up as soon as it was launched.

The other three battalions of the Storm Regiment were to drop by parachute along the coast farther away from Maleme airfield and secure the approaches to the airfield. The 2nd and 4th Battalions of the Storm Regiment, under Major E. Stentzler and Captain Walter Gericke, respectively, dropped west of the Tavronites. These paratroopers reached the ground safely, found their weapons canisters, and formed into cohesive units. Gericke landed closest to the Tavronites, Stentzler farther west. The battalions included two heavy-weapons companies armed with mountain howitzers and antitank guns. Sizing up the tactical situation and realizing that Koch’s detachment was in grave peril, Meindl dispatched Stentzler with two companies from the 2nd Battalion on a wide flank march to the south in the hopes of capturing Hill 107 from the rear. Shortly afterward, Meindl was seriously wounded in the chest and Gericke assumed command of the Storm Regiment.

The unluckiest group of Germans in the Maleme sector was the Storm Regiment’s 3rd Battalion commanded by Major Otto Scherber. Rather than dropping these men onto the beaches as initially planned, the Ju-52 pilots released them onto the short hills beyond the coast road, where they were shot up by the 21st and 23rd New Zealand Battalions. “They were right on top of us,” wrote a New Zealand officer. “Around me rifles were cracking. I had a Tommy gun and it was just like duck shooting.” Some of the paratroopers managed to cut their way through to friendly forces along the Tavronites, while others simply took up defensive positions to await rescue.

Withdrawing from Hill 107

As the day wore on, the 22nd’s Andrew grew increasingly concerned about the consolidation of German paratroop forces along the Tavronites. By the afternoon, Stentzler’s flanking group was putting pressure on Hill 107 from the west. Without any reserve, Andrew requested reinforcements from the 5th New Zealand commander, Brig. Gen. James Hargest, but the request was denied on the grounds that the other three battalions in the brigade were equally hard-pressed. Andrew committed his only two tanks to a feeble counterattack toward the Tavronites bridge. One tank turned back because it had the wrong ammunition; the other got stuck on a boulder in the river bed. In light of the failed counterattack, Andrew began to doubt whether he could hold the hill without reinforcements. At one point, he radioed Hargest that he might be forced to withdraw, to which his superior airily replied, “If you must, you must.”

Prison Valley

The first assault wave at Canea and Suda Bay occurred simultaneously with the airborne attack on Maleme airfield. One formation of 15 gliders led by Captain Gustav Altmann assaulted an antiaircraft battery on the west side of Suda Bay, only to find that it was a dummy position with logs arranged to appear from the air as a working battery. The paratroopers were spotted and rounded up by British reserves stationed around Allied headquarters. The second group was scarcely more fortunate. A formation of about nine gliders led by 2nd Lt. Alfred Genz landed virtually on top the 234th Heavy Antiaircraft Battery. After taking out the battery, the paratroopers were repulsed by Royal Marines when they tried to seize a central wireless station.

The remaining Ju-52s dropped the 3rd Parachute Regiment south of Canea in Ayia Valley for a general advance on Canea and Suda Bay. The area was known locally as Prison Valley because a number of large buildings there formed the island’s penitentiary. The men belonging to the regiment’s three battalions floated to earth around 8:15 am. From their position, they could hear fighting to the north in the direction of Galatos. The 1st and 2nd Battalions landed safely, but the 3rd Battalion was not so fortunate. It landed atop two battalions of Brig. Gen. L.M. Inglis’s 4th New Zealand Brigade and suffered a fate similar to that of Scherber’s 3rd Battalion of the Storm Regiment. Meanwhile, the four gliders carrying the division headquarters, minus Meindl’s glider that crashed before reaching Crete, made a rough landing north of the town of Agia. Lt. Col. Howard Kippenberger, leading the newly formed 10th New Zealand Brigade anchored in Galatos, had made a serious tactical error by not occupying the prison south of his position. The unoccupied compound provided the 3rd Parachute Battalion with a ready-made assembly point from which to launch operations.

The 3rd Parachute faced fierce resistance not only from the Anzac troops in the Canea sector, but also from Greek units assigned to both the Canea and Maleme sectors. The 2nd Greek Regiment was deployed to the southeast of Prison Valley, while the 8th Greek Regiment held the area southwest of Prison Valley, including Agia and the roads passing through it. The German high command had assumed that the Cretans, who had no love for the current regime on the mainland, would welcome the invaders. Just the opposite was true. Greek troops and Cretan citizens hunted the German paratroopers with the same determination as the Allies.

Student waited anxiously at his headquarters for reports of the battle. If the attack had gone well, most if not all of the objectives would be in German hands by noon. Since Greek partisans had cut the lines between his headquarters and the Luftwaffe, he received little information in the first hours of the attack. Without a reliable communications network, Student had no choice but to let the operation proceed as envisioned. The timetable for the second wave, which was to begin departing as early as 1 pm, quickly became unraveled because the refueling had to be done by hand, and the dust created by the rotor wash on unpaved runways reduced visibility during takeoffs and landings. As a result, the planes took off in small groups. Under such conditions, units would be dropped understrength and might be destroyed piecemeal by the enemy.

Retimo

The Ju-52s carrying the second wave of Group Center, consisting of about 1,500 men of the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 2nd Parachute Regiment, arrived over the Retimo sector about 4 pm. The planes flew over the coastline east of the drop zone and turned west to make their drops. As during the drops that morning, the paratroopers were scattered widely over a three-mile area. Lt. Col. Alfred Sturm, who would lead the attack at Retimo, had divided his forces into three groups. The 1st Battalion was to land east of the airstrip and capture it intact, the 3rd Battalion was instructed to land farther west and capture the town and port, and Sturm and about 200 men would attempt to surprise the defenders by dropping directly on the airfield.

Campbell had left the defense of the town of Retimo to an aggressive, 800-strong unit of Greek gendarmes and deployed the two Australian battalions under his command to defend the small airfield located about three miles east of town. His 2/1 Battalion was deployed next to the airfield on a rocky plateau the Allies called Hill A, while the 2/11 Battalion under Major R.L. Sandover was deployed in supporting distance to the west on another promontory known as Hill B. The Australians were dug in tight among the hillside vineyards and determined to hold the airstrip. They had several artillery pieces and two tanks in reserve.

The 500-strong 1st Battalion landed in good shape in and around Stavromenos, just east of the Retimo airfield. The force included the regiment’s heavy-weapons platoon of mortars, antitank guns, and light artillery, as well as a heavy machine gun company. The 800-man 3rd Battalion was not so fortunate. Only half dropped in their intended location, with the remainder landing adjacent to the eastern slope of Hill A, where they were cut down by Campbell’s battalion. Those who landed in the correct location made little headway against the Greek gendarmes. They rushed to take cover among the sand dunes along the beach.

As the 1st Battalion advanced on the airfield, the Australians laid down a wall of fire. Four Australian machine gun teams had stitched themselves into the landscape on the forward slope of Hill A and their fire temporarily halted the better-armed Germans. But the attackers deployed their mortars and methodically set about eliminating the machine gun nests. Outgunned, the Australians pulled back to the reverse slope.

Chappel’s Tanks

The 2,400-strong eastern battle group in the second wave was bound for Heraklion. Chappel, commanding the Allied forces at Heraklion, positioned the various battalions of his 14th British Infantry Brigade, which were reinforced by an Australian battalion, around the airfield east of the city and braced for the pending airborne assault. The transports began appearing at 5 pm, thundering overhead in classic “V” formations to drop their contingents of paratroopers. The drops, which were spread over a 12-mile area, dragged on far longer than planned because of delays at the mainland airfields. As the planes thundered past, the infantry raked the transports with small-arms fire from atop two rocky peaks known as “the Charlies.”

Chappel ordered his reserve tanks into the fight shortly after the paratroopers landed. Two Matildas stationed on opposite ends of the airfield roared to life, as did six more infantry tanks from the 3rd Hussars. The tanks chased down the paratroopers, who were either shot by the tank commanders or run over by the vehicles. Meanwhile, Brauer landed with the 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment, under the command of Major Eric Walther, about a mile east of Heraklion in an area unoccupied by the Allies. Walther’s paratroopers immediately marched to assist their surging comrades.

To the west, the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment, under Captain Gerhard Schirmer, landed and set up a blocking position along the coast road in an effort to prevent Allied reinforcements from reaching Chappel. Captain Karl-Lothar Schulz’s 3rd Battalion landed near Heraklion and immediately attacked the Greek garrison battalion, which Chappel had assigned to defend the town. A fierce firefight developed as the Germans tried to fight their way into the town. As darkness descended, a counterattack by the 3rd Hussars’ tanks drove elements of Walther’s 1st Battalion from the eastern edge of the airfield.

Nightfall in Maleme: Holding by a Bare Margin

When the fighting tapered off after nightfall in the Maleme sector, Freyberg wired Cairo: “The margin by which we hold them is a bare one, and it would be wrong of me to paint an optimistic picture.” Shortly after midnight, Andrew issued orders for the 22th Battalion to fall back to the east. Lacking radio communications with his companies, he sent runners to alert the forward companies to withdraw and begin moving east with Companies A and B. Andrew’s decision was catastrophic to the Allied defense. By retreating from Maleme, he simply turned over the airfield to the Germans. By 5 am, the entire battalion was marching toward ground occupied by other units of the 5th New Zealand Brigade.

Not knowing that the 22nd New Zealand Battalion had abandoned Maleme, the Germans feared that a British counterattack the following morning might solidify the Allied hold on Maleme and drive the Germans beyond the Tavronites. That evening word filtered up to the German high command of a possible debacle on Crete. The first day’s losses, which later were found to exceed 1,800, shocked the German commanders. Under growing pressure to abort the invasion, Student wracked his brain for a way to turn the battle in the Germans’ favor. Working under the assumption that it would be possible to begin landing transports at Maleme on the second day, he ordered 600 reserve paratroopers bound for Heraklion to reinforce the Storm Regiment at Maleme, and instructed Ringel to prepare the first wave of mountain troops to fly to Maleme that afternoon. Transports began landing at Maleme at 8 am on the 21st with supplies and ammunition, but the mountain troops would not arrive until the afternoon. Student ordered four more companies of paratroopers dropped in the sector that afternoon. Two companies dropped safely to the west of the airfield, but the other two dropped to the east of the airfield were badly mauled by the 28th New Zealand.

With the Germans now landing troops directly on the airfield, Freyberg ordered the 20th Battalion, 4th New Zealand, and the 23rd Battalion (Maoris), 5th New Zealand, to retake Maleme airfield. Because the attack involved a complicated reshuffling of troops, the Allied attack did not begin until 3 am on May 22. With less than three hours until daylight, the New Zealanders advanced west along the coast road. The 20th New Zealand moved toward the airfield north of the coast road, while the Maoris advanced south of the road. The New Zealanders quickly became bogged down in house-to-house fighting against isolated groups of paratroopers from Stentzler’s battalion, which had been reinforced. By dawn the Allied force was still short of the airstrip and under attack by Luftwaffe fighters and bombers. The Allies broke off their attack that afternoon.

The Germans Resupply

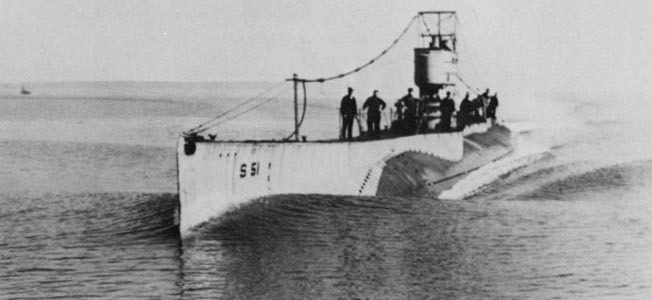

In a significant action at sea that began the night of May 21 and continued the following day, the Royal Navy repulsed two lightly protected German convoys bound for Crete. The first convoy carrying 2,330 men was attacked by a task force made up of three cruisers and four destroyers when it was within 18 miles of Canea. Although most of the Germans were eventually rescued from the water, their vessels loaded with weapons and equipment were sunk. A separate task force composed of four cruisers and four destroyers intercepted a larger convoy carrying 5,000 troops bound for Heraklion less than 12 hours later and forced it to return to the mainland.

Despite occasional shelling, German transports were landing at a rate of 20 per hour, at a time when Allied units were exhausted and running short on ammunition. After its unsuccessful counterattack, Hargest’s 5th New Zealand withdrew east the morning of May 23. As a result, Maleme became fully operational for the Germans, and ME-109s began operating from Maleme airfield. Ringel, who had arrived May 22, divided the troops into three battle groups for the advance from Maleme to Canea. The next day the Germans drove the Allies back onto a series of hills known as Galatos.

When the sun rose on May 25, five resupplied German battalions faced two New Zealand battalions low on ammunition. Throughout the morning, the Germans pounded the Allied positions with mortar and heavy artillery fire in preparation for the assault. At noon, they advanced across the intervening ground. In the fighting that afternoon, Brig. Gen. Hermann Ramcke’s paratroopers overran D Company, 18th Battalion, and the battalion’s other three companies fell back to reorganize. At 4:30 pm, a dozen Stukas screamed down on Major John Russell’s position around Galatos.

The Allied Withdrawal

By late afternoon, a steady stream of Allied soldiers was flowing to the rear. With the withdrawal from Galatos, the last Allied hopes of stopping the German offensive and retaining the island evaporated. The New Zealand Division, along with Vasey’s two veteran Australian battalions, had no other choice but to fall back on Canea. The next morning, Freyberg informed Wavell that the Allies were losing the battle because of the number of fresh German troops arriving daily and the constant harassment by German fighters and bombers. “No matter what decision is taken by the Commanders in Chief from a military point of view our position is hopeless,” he wrote.

As the situation grew increasingly chaotic, Freyberg radioed Wavell on May 27 that the garrison must be evacuated before it was destroyed. Wavell informed Churchill of the situation, and the prime minister reluctantly gave his permission for the British Navy to once again remove Allied ground forces from harm’s way. Wavell suggested that Freyberg retreat east toward Heraklion, but Freyberg planned a fighting withdrawal through the mountains to the small fishing village of Sfakion on the southern coast. From there, the troops from the western sector would be evacuated by ship to Alexandria, Egypt.

Allied Reserves are Crushed

As Freyberg and Weston prepared to depart for Sfakion, the reserve force braced itself to receive the German attack. The attack began at 8:30 am, when German mortars began pounding the Allied positions. Soon, the men on the battle line heard a large volume of fire in their rear. With the continuing influx of reinforcements, Ringel had reorganized his forces into five regimental-size battle groups. Ramcke and the 100th Mountain tied down the reserve’s front, while the 3rd Parachute swung behind, catching it in a classic pincer move. Ringel ordered the 85th and 141st Mountain Regiments to tramp east toward Suda Bay.

The Germans quickly annihilated the reserve force. The front line evaporated and the British soldiers were reduced to fighting in small isolated groups. About one-fifth of the 1,250-man force managed to escape, while the rest were killed or captured. By the time the reserve force was annihilated, the Allied forces in western Crete were in full retreat south toward Sfakion. Ringel assigned Lt. Col. August Wittman, the 5th Mountain’s artillery commander, to lead a motorized vanguard to relieve the 2nd and 1st Parachute Regiments at Retimo and Heraklion, respectively. The force included a battalion each of motorcycle, antitank, motorized artillery, and engineers.

Evacuation

The Allied troops marching toward Sfakion fought a series of small actions on May 28 with elements of the 5th Mountain Division as various elements withdrew south through the villages of Megala Khorakia, Stilos, and Baba Hani. The following day, the Germans divided their forces. The main body, consisting of Wittman’s advance guard and the 85th and 141st Regiments, pushed eastward, encountering little resistance until they reached Retimo later in the day. Deceived by poor intelligence into thinking that only a small portion of the Allies were retreating south, Ringel dispatched a single regiment, the 100th Mountain, to follow the Allies to Sfakion.

As soon as Churchill approved the request to withdraw the Crete garrison, the British Navy steamed into action. Since the deepwater port at Heraklion could accommodate large naval vessels, Wavell and Admiral Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham, the commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Station, decided to withdraw Chappel’s men immediately. On the night of May 28, the Royal Navy loaded nearly 3,500 men onto two cruisers and their destroyer escorts for the voyage back to Alexandria. The force protecting the Retimo airfield had no decent option for evacuation. Lacking a deep-water harbor, Campbell had to decide whether to try to cut his way out toward Sfakion or to surrender. He chose to stay at the airfield in the hope that the Royal Navy would find a way to evacuate his troops from the beaches.

The German force that arrived in the town of Retimo on May 29 outnumbered and outgunned its foes. Not only did Wittman have artillery, antitank weapons, and mortars, but the Germans had offloaded tanks at Kastelli, a seaside village west of Maleme, which had joined Wittman’s command. The Germans called on the Allies to surrender, shouting, “The game’s up, Aussies!” Campbell surrendered along with about 700 men, but Sandover and 51 others retreated into the hills, where they held out for several months until a submarine picked them up.

The evacuation from Sfakion was carried out over a four-day period from May 28 through May 31. The Allies established a screen of units on a wide front to keep the 100th Mountain from interfering with the evacuation. The task force assigned to the evacuation sailed to Sfakion for the last time on the evening of May 31. Nearly 4,000 troops were carried back to Alexandria that night when the ships raised anchor at 3 am. Nevertheless, a large number of Allied troops were left behind. On June 1, Lt. Col. Theo Walker of the 2/7 surrendered 5,000 Allied troops to an Austrian officer of the 100th Mountain.

Between the evacuations from Heraklion and Sfakion, the Royal Navy transported about 16,000 Allied troops to Egypt. Although the Germans had driven the garrison from the island and captured its three airfields intact, they had suffered serious casualties. From an assault force numbering 22,000 paratroopers and air landing troops, the Germans had recorded nearly 6,500 casualties, including 3,352 killed or missing in action. More than half of the losses occurred on the first day among the unfortunate paratroopers of the 7th Air Division. The Allied forces, excluding the Greeks, suffered about 3,500 casualties, including 1,700 killed. Far worse was the fact that 12,000 British and Anzac troops were taken prisoner. Since the Greeks were not evacuated, the roughly 10,000 who survived the battle also went into captivity.

Conclusions from the Battle

The Allies lost the battle largely because of confused communications and miscalculations at headquarters. Had he taken the initiative, Freyberg had the resources at hand to defeat the Germans during the first few days of the battle. However, he refused to commit his reserves in the Canea-Suda sector to keep Maleme airfield out of German hands. Throughout the battle, Freyberg remained fixated on the idea that the Germans planned a simultaneous beach assault, and he withheld key reinforcements from the main battle. Still, the Allied forces fought heroically, and Freyberg’s ability to conduct a fighting retreat enabled the Royal Navy to extract more than 16,000 soldiers—nearly two divisions’ worth of infantry.

For Student, the triumph at Crete was bittersweet. Not only had he seen his beloved 7th Parachute Division mauled by the enemy, but the days of large-scale German parachute drops were over. On July 19, Hitler summoned Student and other senior parachute commanders to his headquarters. After congratulating each of them and presenting them with the Knight’s Cross, the Führer took time to confer separately with Student. He stunned the architect of the German parachute troops by telling him that, from then on, paratroopers would play a less active airborne role in the war. “Of course you know, General, we shall never do another airborne operation,” Hitler said. “Crete proved that the days of the parachute troops are over.” Three years later, in Normandy, the Allies would prove him wrong.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments