By Kelly Bell

By 167 bc, when a full-scale revolt erupted in Judea, it had been more than 400 years since an organized Jewish army had taken up arms against an enemy. In 586 bc, the valiant defenders of Jerusalem had fought a hopeless battle against a massive Babylonian invasion force. After that, the only Jewish warriors were those occasional mercenaries who enlisted for pay in the causes of other nations. The Judean revolt’s roots went back to 198 bc, when Syria’s Seleucid dynasty forcibly took Palestine from its previous rulers—the Egyptian Ptolemies. Both these Gentile factions were descended from Greek generals (Seleucus and Ptolemy) who had inherited the regions 200 years earlier after their master, Alexander the Great, died childless in 323 bc.

A Change in Policies

At first, the changeover in occupying forces had little effect on the Jews, who remained free to practice nominal self-government and, most importantly, their faith, under their new ruler, Antiochus III. Tolerant administration had always been the policy of the Ptolemies, and generations of Judeans had become accustomed to benign overlords. But upon the death of Antiochus III and the ascension of his son Antiochus IV Epiphanes in 175 bc, intolerance and tension began to grow in the Jewish homeland.

Caught between hostile Egypt to the south and the looming proximity of Rome to the northwest, the Syrians also faced threats from the ambitious Medes and Parthians to the southeast. The situation instilled a great deal of understandable uneasiness in Antiochus IV, who realized that with its proximity to Egypt and its commanding heights overlooking the vital coastal trade route, Judea had to be strongly secured for strategic reasons. He resolved to do this via the arbitrary imposition of Greek ritual and culture on its Jewish inhabitants in an attempt to establish a common language and the practice of overall Grecian civilization to create unity in his empire. This attempt to force paganism on the Jews would prove to be a mortal mistake.

Issuing orders for the Hellenization of Judea in 168 bc, Antiochus departed to attack the Egyptians, apparently never considering the possibility of armed resistance from the long-sedate Jews. The Jews, however, were implacably devoted to their god Jehovah, and the majority of them considered idolatry inconceivable. Tensions rose. Apart from their centuries of docility, however, the Jews were hampered in their resistance by their relatively sparse numbers. The population of Judea at the time was 250,000 at most, with only a fraction of these being able-bodied young men. This too may have led to the seeming casualness on the emperor’s part when he enforced idolatry upon his presumably meek subjects. Things were about to go terribly wrong.

Failure in Egypt, Opportunity in Jerusalem

When Antiochus laid siege to Alexandria, Italian emissaries quickly informed him that if he did not desist, Roman intervention would immediately ensue. Saddled with such a preponderance of enemies, he wisely yielded, broke off his investment, and withdrew along the coastal highway. By this time, defiant Jews had already rioted in Jerusalem. Learning of this, a humiliated and worried Antiochus was delighted by what he saw as a glittering opportunity to salvage the prestige lost in the abortive Egyptian campaign. Here was a war he could claim, however implausibly, was forced upon him by an enemy that he could easily crush. Afterward, he could trumpet this victory to the seemingly endless array of bellicose neighbors, who might think twice before attacking him.

Antiochus dispatched one of his most competent generals, Apollonius, to quell the Jewish insurrection. The Seleucid troops massacred most of the Jewish population of Jerusalem, burned revered documents containing Mosaic law, and threw young mothers and their newly circumcised infant sons to their deaths from city walls. They also looted the temple and desecrated its holy sanctuary by converting it into a shrine to Zeus. Word spread swiftly. In his overconfidence, Antiochus overlooked the fact that the army he had sent against the Jews was not of the highest caliber. These troops were not led by inspiring campaigners like Alexander, nor were they the well-trained, well-equipped, and well-motivated legions of Rome. Instead, they were a motley aggregation of conscripts and mercenaries whose abilities and incentives varied greatly. Most had little field experience in the phalanx and cavalry tactics devised earlier by the Greeks. The Seleucid force also contained some Jewish soldiers of fortune who were as infuriated at the Syrians as were the insurgents. These men quickly defected to the rebels and contributed their crucial experience and military training to the patriot cause.

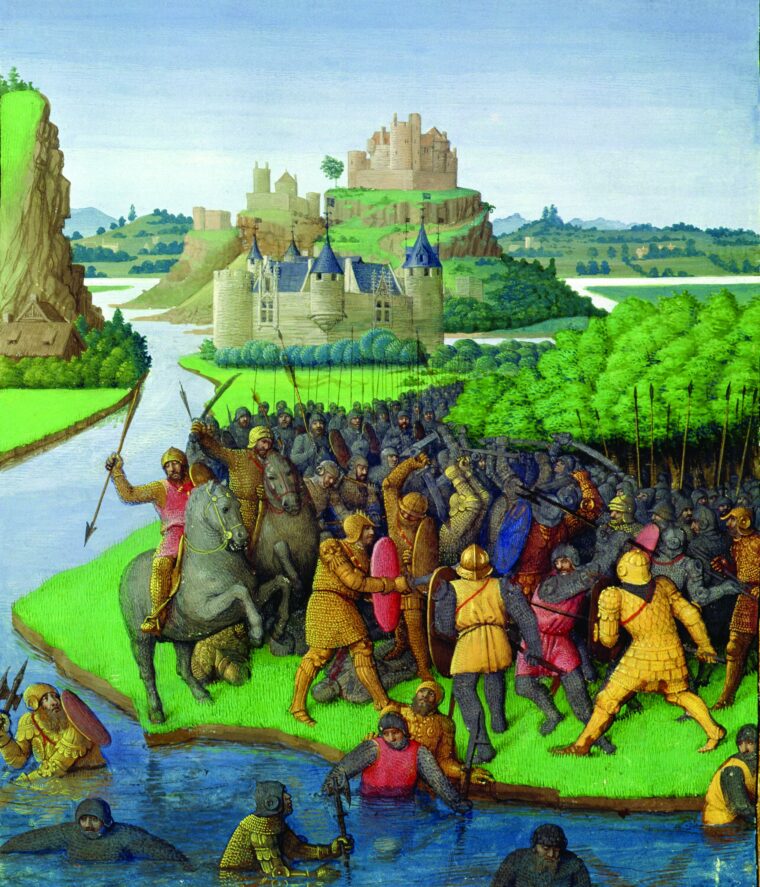

The Maccabean Revolt

After bloodily securing Jerusalem, Antiochus sent his forces into the unfamiliar Judean hill country to finish the task of Hellenization. An officer named Apelles led a patrol into the village of Modiin and ordered the local priest, Mattathias, to blasphemously sacrifice a pig, which Jews regard as an unclean creature. When Mattathias refused to comply, another Jew offered to perform the sacrilege, whereupon the aged holy man whipped out a dagger and killed both the traitor and Apelles. Mattathias’s five sons incited the townspeople to rise against the invaders and wiped them out, marking the first in a lengthy string of reverses for the Seleucids in what came to be called the Maccabean Revolt.

Leading his small band of about 200 people (with perhaps 50 fighting men) into the easily defended Gophna Hills, Mattathias commenced training the peasants in the guerrilla tactics he realized were their only hope against the mighty Seleucid empire. Since no Syrians had escaped Modiin, it took time for their main force to learn of their comrades’ demise. (Or perhaps they assumed the missing unit had simply deserted, a not uncommon practice for this particular army.) In any case, it took a year for the invaders to react. By this time, Mattathias had died and had been succeeded by his middle son, Judas (also called Judah). The Jews had productively spent the hiatus training, recruiting, and gathering information. Judas constructed an efficient intelligence-gathering apparatus while sending out agents to spread word of the revolt, enlist new men, and collect whatever weapons could be found or fashioned.

Capturing the Tools of Victory

Apart from a few rusty heirlooms, arms were few. Judas would have to make do with modified farm implements until up-to-date weapons could be captured. If early battles could be won, he reasoned, the enemies’ swords, armor, catapults, spears, javelins, bows, slings, shields, and battering rams would be a windfall. Until then, Judas realized, he would have to move slowly. He had his steadily growing forces ambush and annihilate Seleucid patrols, amassing a new arsenal in the process. He also spent a great deal of time with his lieutenants, formulating unconventional tactics for which his dogmatic opponents would be unprepared. The Maccabees’ hit-and-run tactics increased their fighting strength and kept the Seleucids befuddled, off balance, and generally in retreat. As the surrounding countryside slowly came under Jewish control, the Syrian garrison in Jerusalem was isolated and in danger of being overwhelmed or simply starved into submission. When word of the grave situation reached Apollonius at his headquarters in neighboring Samaria, he moved tardily to intervene.

It was time for Judas and his men to mount their first major field operation. The Seleucids’ favored battle tactic was the phalanx. Heavily armored infantry would draw together in a tight formation, as if on parade, with the men in each line shoulder to shoulder and closely following the rank in front of them. The smallest phalanxes contained 2,000 men spread over an area 120 yards wide by 15 yards deep. The warriors in the first five lines held their spears horizontally, while the 11 lines following them held theirs aloft, essentially in reserve for those rare occasions when they were needed. Flank protection was provided by cavalry and less heavily armed infantry. It was a powerful but unwieldy formation that compromised the element of surprise.

Raised and trained in this traditional method exclusively, the Syrians had never considered the benefits of interfering with an opponent’s deployment or altering their tactics to exploit battlefield circumstances. Since these head-on shoving matches were the only stratagem they had ever used, the possibility of fighting in any other fashion never occurred to them. Judas and his comrades, on the other hand, had never waged any kind of large-scale combat before, and they were careful to consider all options. For the invaders, an unconventional test of nerves was looming.

Sometime in 166 bc, Apollonius’s 2,000-man expedition advanced on Jerusalem via the mountainous route from Samaria. Skirting the Jews’ Gophna stronghold to the west, the Seleucids passed through terrain marked by craggy defiles and canyons perfect for ambush, but since they had never heard of an ambush, they did not guard against one now. Dividing his 600 men into four units, Judas deployed at Nahal el-Haramiah a few miles northeast of his headquarters. Blithely unaware of the suicidal blunder they were committing, the Syrians marched in orderly rows into a narrow passage flanked by hundreds of well-trained and highly motivated Jewish warriors.

It was late afternoon when a sealing unit fell upon the vanguard of the column, causing great confusion and havoc. Troops to the rear could not see what was going on and continued to press forward, bunching the regiment into a mass of flailing, panicky men unable to comprehend what was happening to them. The valley’s eastern slope came alive with the main Judean force, which smashed into the Seleucid flank while the third and fourth attacking units moved in from the north and east. Jewish archers killed Apollonius; and his leaderless, trapped, and totally confused men were left to fend for themselves in a type of battle they had not known existed. In short order, the Syrian forces were wiped out en masse, and their weapons and equipment fell into the rebels’ eager hands.

The smashing victory provided the Maccabees with a crucial boost in confidence. They began to think of outright independence rather than mere survival. The Judean army was swelling, and its commander was far superior to his counterpart, General Seron, who was overconfident and all too eager to reach the trouble spot, crush the insolent band of renegades, and boost his own standing in the army. Seron had a low opinion of Apollonius’s ability and saw his incompetence as the sole reason for his defeat, not considering the possibility that Judas and his officers were brilliantly adaptable. The only apparent adjustment Seron made was to march his force along the Mediterranean shore with its broad coastal plain, thus precluding ambush. Turning inland in the vicinity of Jaffa, the Seleucids passed Lod en route to their surrounded comrades in Jerusalem. After combining their forces, they would fan out into the countryside in a sweeping search-and-destroy campaign against the Jewish rebels.

A Second Success: The Battle of Beth Horon

Hoping to elude detection, Seron made for the city via a secondary route through the pass at Beth Horon. Jewish lookouts immediately noticed, however, and Judah prepared to take full advantage of a handy bottleneck he knew along the trail. The 1,000-man Maccabean army prepared to destroy the invaders. The ascent to the pass was flanked by steep slopes perfect for ambush, and Seron took the precaution of having his command file through with long gaps in individual units, making the entire column over a mile long and impossible to trap in its entirety inside the canyon.

Armed with the sword he had taken from Apollonius’s corpse, Judas personally led the sealing unit that attacked and decimated the Seleucid vanguard and made a point of quickly killing the general. Seron was one of the first men to die in the engagement, as Jewish archers on both slopes unleashed a lethal volley from their bows and slings. As the column’s leading elements staggered back in disorder, the Jews attacked with their recently won swords. Again seized by fear, shock, and utter bewilderment, the Syrians hastily retreated, leaving behind 800 dead and the bulk of their equipment. As the rear elements turned and fled, the rebels took up the chase, pursuing them to the coastal plain and killing many more Syrians.

When news of the triumph spread through the hills, Judas’s army expanded to more than 6,000 men, with recruits streaming in from all parts of Judea. Antiochus finally comprehended that his opponent was a natural military genius, gifted in the uses of opportunity, terrain, surprise, morale, and confidence. Judas’s veterans were also doing a masterful job of training the mass of newcomers in using the latest batch of captured armaments.

“Uproot and destroy the strength of Israel”

At this point, an unrelated civil war broke out in the eastern region of the Seleucid Empire. Word of Seron’s fate reached Antiochus as he was preparing to quash this mutiny and replenish his dwindling financial reserves. He elected to go ahead with his domestic mission and entrust dealing with the Judeans to his relative, Lysias. However, he had a problem always associated with a two-front war—limited manpower. A substantial percentage of the Syrian forces earmarked for the domestic unrest had to be siphoned off to Judea.

Lysias’s military experience was limited, but it did not take an Alexander to understand the emperor’s instructions to his embarking kinsman: “Uproot and destroy the strength of Israel and the remnant of Judea. Blot out all memory of them in the place. Settle strangers in the territory and allot the land to the settlers.” Lysias, perhaps wisely, did not deign to lead the expedition himself. He gave the task to Generals Ptolemy, Nicanor, and Gorgias. Setting out in the spring of 165 bc, the Syrian force numbered about 20,000 men. Pitching an enormous base camp at Emmaus in the foothills just above the Ajalon valley, the triumvirate felt certain they would not be taken unaware in a narrow canyon. They were determined to engage their opponent on open ground, without giving adequate thought or preparation to the enemy’s already well-established adaptability.

The Revolt Reorganizes

Judas had organized his army into smaller, more manageable units able to fight independently in a somewhat more conventional manner. The Syrians would not be facing a strictly irregular force this time, but a well-trained and well-motivated professional army fighting for its survival against opponents who were there for no other reason than to obey orders. While both sides were making last-minute preparations, the Seleucids were unexpectedly reinforced by a number of fresh troops from Idumea, just south of Judea. The sprawling bivouac was further crowded by masses of camp followers and slave traders who anticipated a bonanza of merchandise after the expected defeat of the Jewish insurgents. Apart from chains and whips, the slavers also brought hefty amounts of gold and silver in preparation for setting up a lucrative market. The camp was becoming a richer prize by the hour.

Judas and his brothers Simon, Johanan, and Jonathan commanded four 1,500-man brigades, which they assembled at Mizpah on the road to Beth Horon immediately northwest of Jerusalem. After confirming the enemy’s position, Judas moved his headquarters to a hilly area near Latrun. The opposing camps were now within eyesight of each other, and the rebels decided to let their foes make the first move. They could see from the swarming patrols and bustling activity that the Syrians were preparing to attack first anyway.

Judean Ambush at the Battle of Emmaus

Gorgias intended to surprise the Jews by assaulting them at night, but the Maccabean espionage network made sure that its commander in chief was forewarned, and he quickly devised a countermeasure. Ordering a number of bonfires lit, Judas gave Syrian scouts the impression that his camp was fully manned, while he withdrew the bulk of his troops and left a skeleton crew to tend the fires and act as decoys. When Gorgias’s 6,000-man force surged into the Jews’ former positions, it found only the rear guard, which fled into the Shaar Hagai valley. In the darkness, the Seleucids predictably mistook this small band for the main body of revolutionaries and set out in pursuit through the narrow defile, where they were bushwhacked by 1,500 waiting warriors.

Judas had positioned another 1,500 men north of the Syrian camp to assault it from the rear when he and his remaining 3,000 soldiers launched their planned daybreak attack, but the enemy had its own spy ring and was alerted to the rebels’ approach. Judas was stunned to find the opposing army fully prepared for battle, drawn up in its phalanx on the plain in front of its camp at daybreak.

With the critical element of surprise gone, Judas again called upon his resourcefulness and divided his command into three 1,000-man battalions to strike the Seleucids in their vulnerable western flank. While one of these groups engaged the covering cavalry, the other two assailed the enemy formation from the side. Fortunately for the Jews, the bristling phalanx was facing south, and they had appeared to the west. Had they come up directly in front of it, they probably would have been unable to make their countermove without the Syrians noticing and turning to face them. As it was, the Seleucids, still knowing just one way to fight, began to yield in bloody hand-to-hand combat.

There were still some 12,000 soldiers in the Emmaus encampment. These had not expected to have to fight that day, assuming that Gorgias’s phalanx would shield them from the enemy. When the sound of the battle reached the 1,500 Jewish troops to the north, they assumed that their camp was under assault and charged down from their hidden position. This attack caught the numerically superior Syrians completely off guard, and the Seleucid forces were thrown into disarray. By this point, the phalanx was collapsing and its survivors were retreating in terror to the presumed safety of their base. But upon reaching it, they were caught up in grisly pandemonium and cut to pieces among stampeding horses, freight-carrying elephants, and terrified slave traders and their entourages.

After the Jews had killed 3,000 of Nicanor’s men, the remnant fled toward the coast. With remarkable presence of mind, Judas forbade his men to pursue them or begin looting—Gorgias had not yet been finished off. Setting fire to the camp, the Jewish warriors sent thick columns of smoke aloft, drawing Gorgias’s attention away from the small force harassing him. Fearing that they would soon be caught between two bodies of expert, determined warriors, the remaining Syrians succumbed to fear and joined the mass flight to the seacoast, hotly chased by the entire Judean army. The rebels, meanwhile, helped themselves to the copious treasures of the enemy encampment, including another cache of weapons and other equipment.

A Hasty Advance, a Quick Retreat

Things looked bleak for the Jews’ reeling overlords. Lysias survived the destruction at Emmaeus, made it back to Antioch, and wasted no time in raising another force to resume the conflict. Still hoping to join forces with his Jerusalem garrison, Lysias again set out along the coastal route, but this time he bypassed the lethal uplands and approached through friendly territory, turning north and setting up camp at Beth Zur in southernmost Judea. Intending to march his force of 24,000 men to Jerusalem and establish it as an impregnable nerve center for his forces throughout the region, Lysias began fanning out his troops in all directions from the Holy City, stamping out rebel resistance as it was encountered. The flaw with this scenario was that there was no way to reach Jerusalem without traversing the highlands, and the Jews had massed in the ravine-bisected region around Hirbet Beth Heiran.

Judas divided his troops into four units of varying size, with 5,000 men held in reserve. As the Hellenist columns filed through yet another of Judea’s treacherous canyons, they were once again ripe for the slaughter. Lysias had impatiently pulled together a large body of mercenaries and untested, poorly trained conscripts with the intention of overwhelming the revolt through sheer force of numbers. The size of his force made it easy for the Maccabees to track as it tramped conspicuously along the flat coastal plain. Lysias set himself up for disaster when he turned inland and entered the hill country after establishing a base camp on the upland border.

Trudging uphill under the weight of their armor and weapons, the Seleucids were totally vulnerable when 3,000 screaming Jews charged from a just-bypassed gully. The unprepared, unmotivated invaders at the head of the column quickly broke and commenced streaming back the way they had come. The mass flight panicked the following units, which were then assailed from both sides of the canyon by two 1,000-man Jewish columns. There were still 8,000 Syrians in the base camp, and to engage them Judas had set aside the 5,000-man reserve force. However, the encamped Syrians immediately took to their collective heels as the decimated advance units fled through their midst with hordes of shrieking Jews in eager pursuit. By the time the Jewish warriors reached the enemy bivouac, they found no enemies left to fight—they had all stampeded south to the relative security of the Idumean city of Hebron.

Besieging Acra

Judas decided not to chase his beaten enemies into hostile territory. He had already killed 5,000 of them in yet another military disaster for the unfortunate Antiochus. With his keen analytical mind, Judas realized that his latest victory had been made much easier than it might have been simply because his counterpart had allowed anger, impatience, arrogance, and fear goad him into acting without adequate preparations. The rebel warlord correctly assumed that his enemy would not yet give up the fight. The Seleucids were certain to reach out to a more capable commander and send him into Judea with another formidable army. But racked by an internal power struggle, the Syrian regime was in no position to embark on another punitive expedition. There was a hiatus in the war, and Judas spent the lull proclaiming to his countrymen their independence and restoring freedom of worship.

There was still the matter of the obtuse Jerusalem garrison, whose members had spent the past few months fortifying themselves and stocking their stronghold with food, water, and weapons while Judas was occupied elsewhere. Part of the Syrian force was entrenched in a fortress called the Acra, and the Jewish patriots attacked this position soon after entering the city following Lysias’s defeat. While fighting was still in progress, holy men entered the temple, restored it, and removed the pagan profanations. The Talmud records that after the priests consecrated and rededicated the sanctuary in 164 bc, a one-day supply of oil burned for eight days. This miracle marked the beginning of the festival of Hanukkah.

Syrian forces elsewhere in the area, unwilling to confront the Maccabees in pitched combat, assaulted unarmed civilians in Galilee and Gilead, east of the Jordan River. Dispatching to Galilee a 3,000-man rescue expedition commanded by his brother Simon, Judas took another 8,000 men, forded the Jordan, and embarked for Gilead through the Trans-Jordan desert. Simon quickly defeated a small enemy force, rescued prisoners, and returned with them to Judea. Meanwhile, Judas concentrated on a string of fortified towns east of the Golan Heights. Starting with Bostra, he invested and overwhelmed each settlement’s Hellenist occupiers until coming at last to Dathema, which was under siege by Seleucid and Idumean troops who were scaling the outer walls. Slicing into the surprised besiegers from the rear, Judas quickly put them to flight.

He next made an exploratory foray to the northwest and engaged the new Syrian commander, Timotheus, who counterattacked out of the city of Raphon. Judas not only turned back this thrust, but also captured and sacked the city. Having delivered the persecuted Jews of Gilead, he fought his way back through hostile territory and returned to Judea. At about this time, word arrived in Judea of the death of Antiochus and a resultant power struggle between his son Antiochus V Eupator and the late ruler’s regent, Phillip. Realizing the already weakened Seleucid Empire was in turmoil, Judas decided to take advantage of his captured siege equipment and invest the Syrian-held fortress at Acra.

The next Maccabean attack on the bastion came early in 162 bc. The defenders fought it off, aided by the sizable contingent of Hellenist Jews within the fort who were fearful of being executed as traitors should they be captured alive. After the initial storming attempt, Judas reassembled his soldiers into siege positions to compel a slower but inevitable surrender. Syrian agents escaped from Acra and made their way back to Antioch, where they begged Lysias to relieve the embattled defenders.

A Wise Retreat

The Maccabees had not expected Lysias to leave his capital until after settling with Phillip, but Phillip was off campaigning against Lysias’s forces in the east and was momentarily out of the way. Mustering an army of 30,000 heavily armed men and 30 war elephants, Lysias set out for Jerusalem via the same route he had taken the last time, approaching from the south. This army attacked the border town of Beth Zur, forcing Judas to leave off besieging Acra and hurry to meet the unanticipated threat. Evidently thinking that the best way to surprise his enemies was to act conventionally, Judas did not attempt to relieve Beth Zur, but instead took up positions 12 miles south of Jerusalem at Beth Zecharia. After securing Beth Zur, Lysias marched out to meet his longtime nemesis. Having ruefully learned his lesson, he deployed units on the flanking high ground to screen him from any more avalanches of screaming rebels cascading onto unguarded flanks.

For the first time, the Maccabees were fighting a defensive battle. It was an unfamiliar sensation, and the hulking, armored elephants unnerved them. In desperation, Judas’s younger brother Eleazar ducked under one of the behemoths and thrust his sword into the animal’s chest, killing it. The pachyderm fell and crushed the young warrior—the first of Judas’s siblings to die in combat. The Syrians were finally fighting the kind of battle for which they had been trained, and they pressed irresistibly forward, crushing the Jews by force of numbers.

Ignoring any pangs of pride or wounded ego, Judas wisely ordered retreat. Electing to not try and defend Jerusalem with his battered army, he stopped just long enough to fortify the Temple Mount before withdrawing to Gophna. When they entered the city, the invaders immediately assailed the temple garrison, but they were bloodily repulsed. The insurgents were praying the Seleucids would not learn of a serious shortage of food and other supplies that was endangering the entire revolution, and faraway upheavals again came to the Jews’ aid.

A Short Peace

Messengers informed Lysias that Phillip was en route back to Antioch, fully intending to take over the government. On the brink of his sorely needed and unexpected victory, the Seleucid leader was trapped in a dilemma, but he devised an ingenious solution. Realizing that the revolutionaries would be unaware of the situation with Phillip, he offered a truce to the surprised Judas, promising a degree of autonomy and religious freedom. After the Maccabees accepted the terms, Lysias hurried back to Antioch, crushed Phillip’s forces, and consolidated his position as Seleucid ruler—briefly.

Emperor-to-be Antiochus V Eupator was just nine years old in 162 bc when his cousin Demetrius was freed by the Romans, who had been holding him as a political hostage, and returned to Antioch. Demetrius quickly gained popular support, seized power, and executed Lysias and the young Antiochus. Demetrius reimposed the oppression in Judea, and the Maccabees, who had ruefully sworn off conventional tactics, resumed their irregular resistance, ambushing and routing a large Syrian force commanded by General Nicanor just north of Jerusalem in the spring of 161 bc. Nicanor’s head and hands were hung from the temple gate.

The Revolt Collapses

Following this impressive showing, Judas cleverly negotiated a treaty of alliance with Rome that recognized Judea as an independent state. For the first time since before the Babylonian exile, the Jews had their own sovereign nation. Demetrius feared a Rome-supported Judea might induce another of his inherited enemies, Egypt, to join the alliance and invade his empire through Judea. Basing his actions on reports that the Maccabean army was disbanding, Demetrius dispatched a 24,000-man expedition in the spring of 160 bc. Sure enough, Judas was unable to mobilize more than 3,000 troops. Joining battle at Elasa, about six miles east of Beth Horon, the armies clashed briefly before the Jewish warriors, demoralized by the eight-to-one odds, broke and fled, leaving their peerless commander with just 800 valiant veterans. Leading his small band in a desperate charge on the enemy’s right flank, Judas killed a great number of Seleucids but failed in the crucial objective of killing their commander, General Bacchides. Instead, Judas and his little group of loyalists were wiped out.

It had taken the Syrians far too long, but in Bacchides they finally found a leader capable of concocting viable strategy and instilling needed flexibility into Syrian formations. Considering the overpowering numerical advantage the Syrians enjoyed in that April clash, it could be said the Maccabees were drawn into a trap even if they realized it from the beginning, for they could not afford to allow this pagan multitude to rampage unchecked throughout Judea. Confronting it when they did, before they had time to assemble sufficient soldiers, was unavoidable—and fatal.

The Legacy of Judas Maccabeus

For no small reason, Judas was called “the Hammer.” His unparalleled battlefield adaptability, proficiency in exploiting an enemy’s mistakes, ability to fight at night, and effective use of terrain, surprise, and espionage made him the bane of succeeding Seleucid commanders. After Judas’s death, his brothers Jonathan and Simon eventually achieved the Judean dream of religious and political independence. It was the first time in recorded history that a subject people had won a revolutionary war for religious freedom.

Because he fought in just one poorly chronicled war, Judas Maccabeus has largely been lost among the giant shadows cast by Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Genghis Khan, Napoleon Bonaparte, Shaka Zulu, and other great conquerors. Unlike them, Judas was a man of noble motives who fought because he had no other choice. Unfettered by outmoded convention, he taught himself and his followers to fight via methods too subtle to be perceived by their powerful but outmoded adversaries. Today’s high-tech military strategists would be well served to study the humble partisan leader of long ago, who wanted nothing more for himself and his people than to be allowed to live and worship in peace.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments